Xipe Totec

Overview

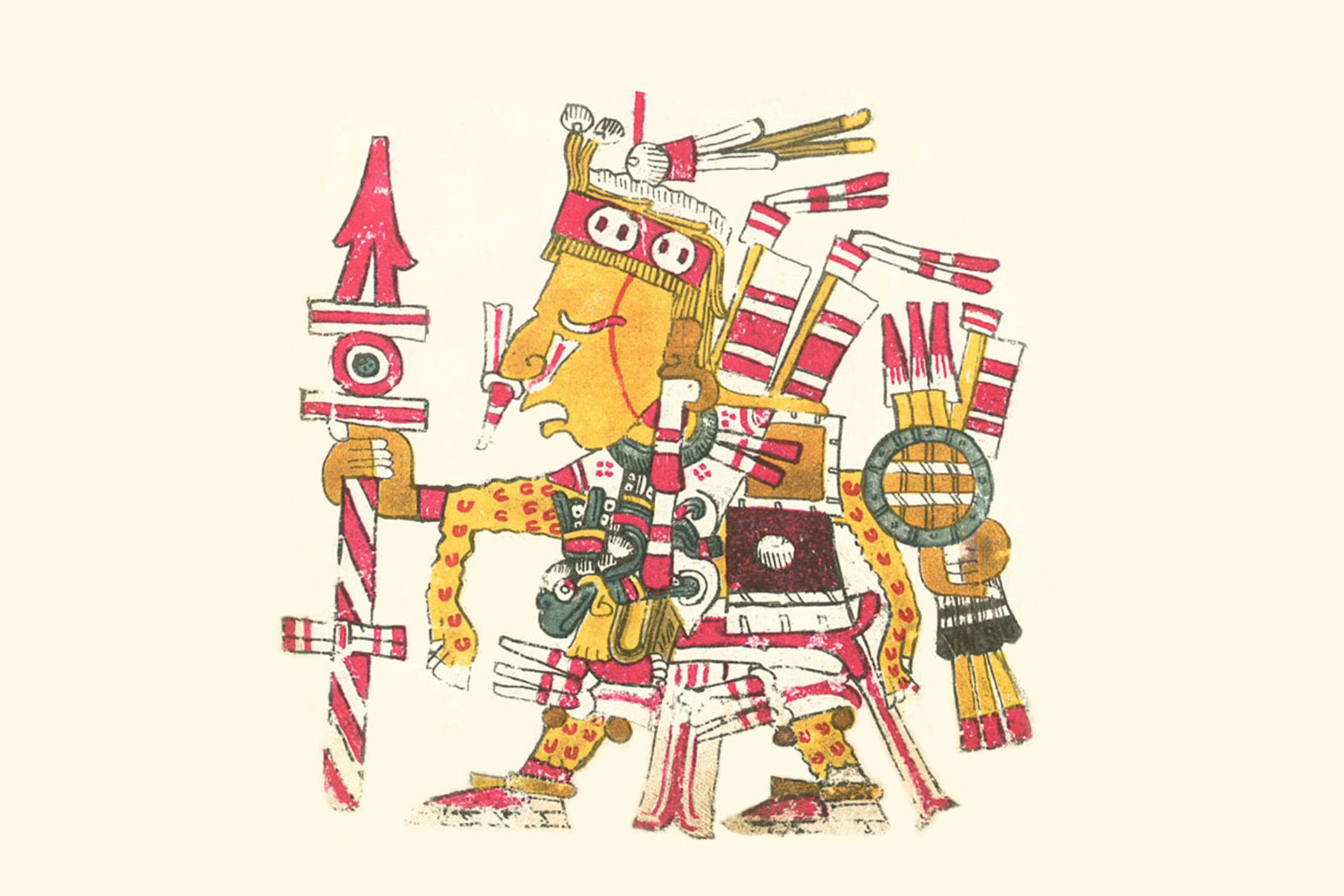

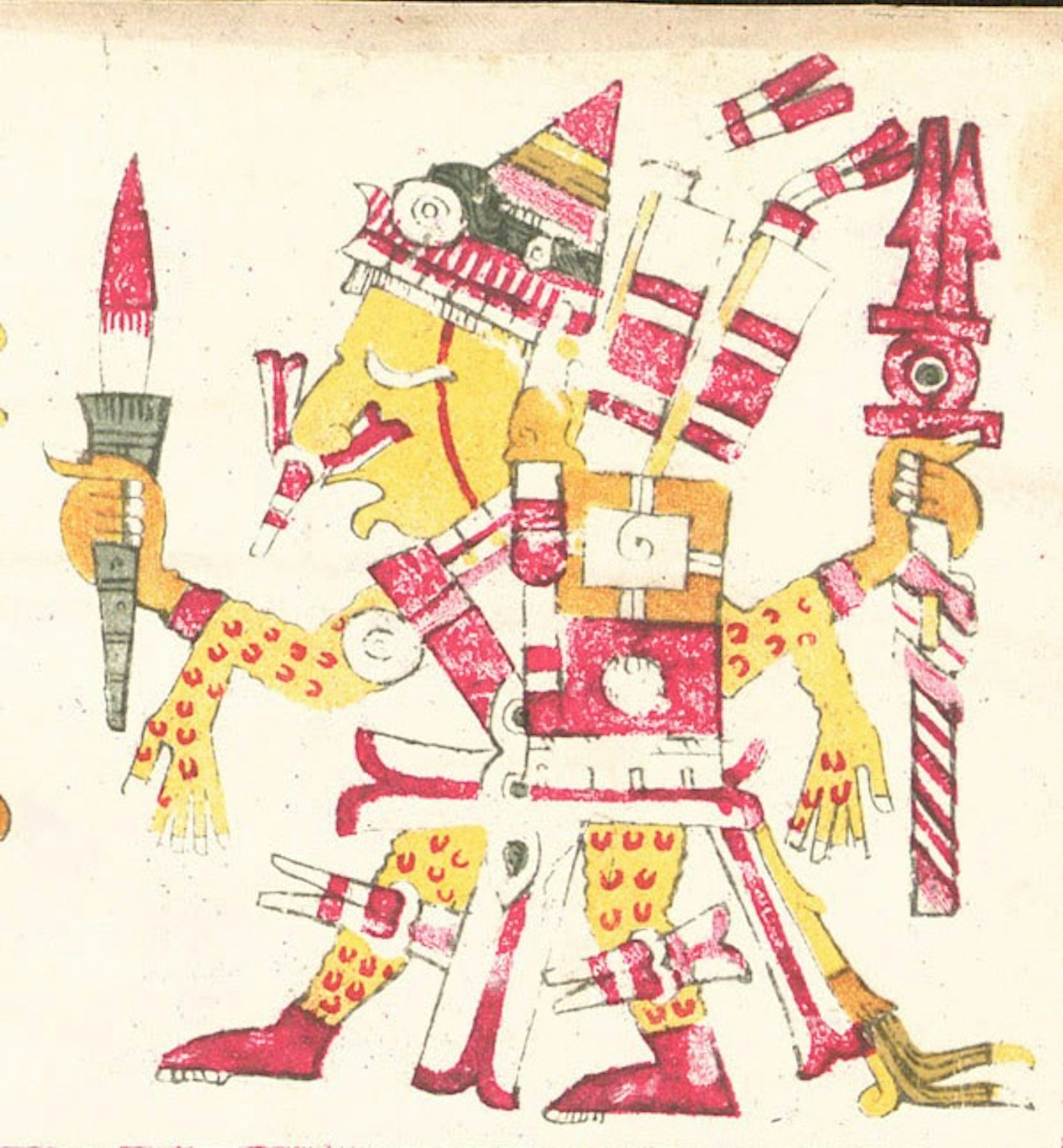

Xipe Totec was the Aztec god of agriculture, seasons, goldsmiths, and disease. He was often depicted wearing a suit of flayed skin, and his associated ceremonies emphasized his choice of attire. Such rituals usually culminated in a fresh skin suit being made and worn by either a statue of Xipe Totec or one of his priests.

Xipe Totec as depicted in the Codex Borgia.

Codex BorgiaPublic DomainUntil recently, historians were reliant on post-conquest Spanish texts for information about the origins and worship of Xipe Totec. In 2018, however, an excavation in Puebla, Mexico revealed a temple dedicated to his worship. The temple, which was dated to between 1000CE and 1260CE, belonged to the Ndachjian-Tehuacan people who were later conquered and absorbed into the Aztec Empire.[1] The Aztecs may have already regarded Xipe Totec as one of their major gods prior to this conquest, as they shared a significant portion of their pantheon with neighboring ethnic groups.

Etymology

While some Aztec gods had names that require interpretation to understand, Xipe Totec’s name simply meant “Our Lord the Flayed One.”[2] This was an apt name, as he was nearly always depicted wearing the flayed skin of a sacrificial victim.

Xipe Totec was known by other names as well, including Tlatlauhca, Red Tezcatlipoca, Yoalli Tlauana (Night Drinker), Tlaclau Queteztzatlipuca, and Camaxtli.[3]

Attributes

According to the Codex Ramirez, Xipe Totec was “born of a ruddy color all over,” thus explaining his title of Red Tezcatlipoca. In most artistic portrayals, Xipe Totec wore a suit of flayed skin that was typically yellow or golden in color; his own exposed skin was usually shown in red.

Xipe Totec’s suits of flesh were quite intricate and included stitching over the chest where the sacrificial victim’s heart was removed prior to the flaying. The suit's hands hung loosely at the wrist, and Xipe Totec’s own hands were left uncovered.[4]

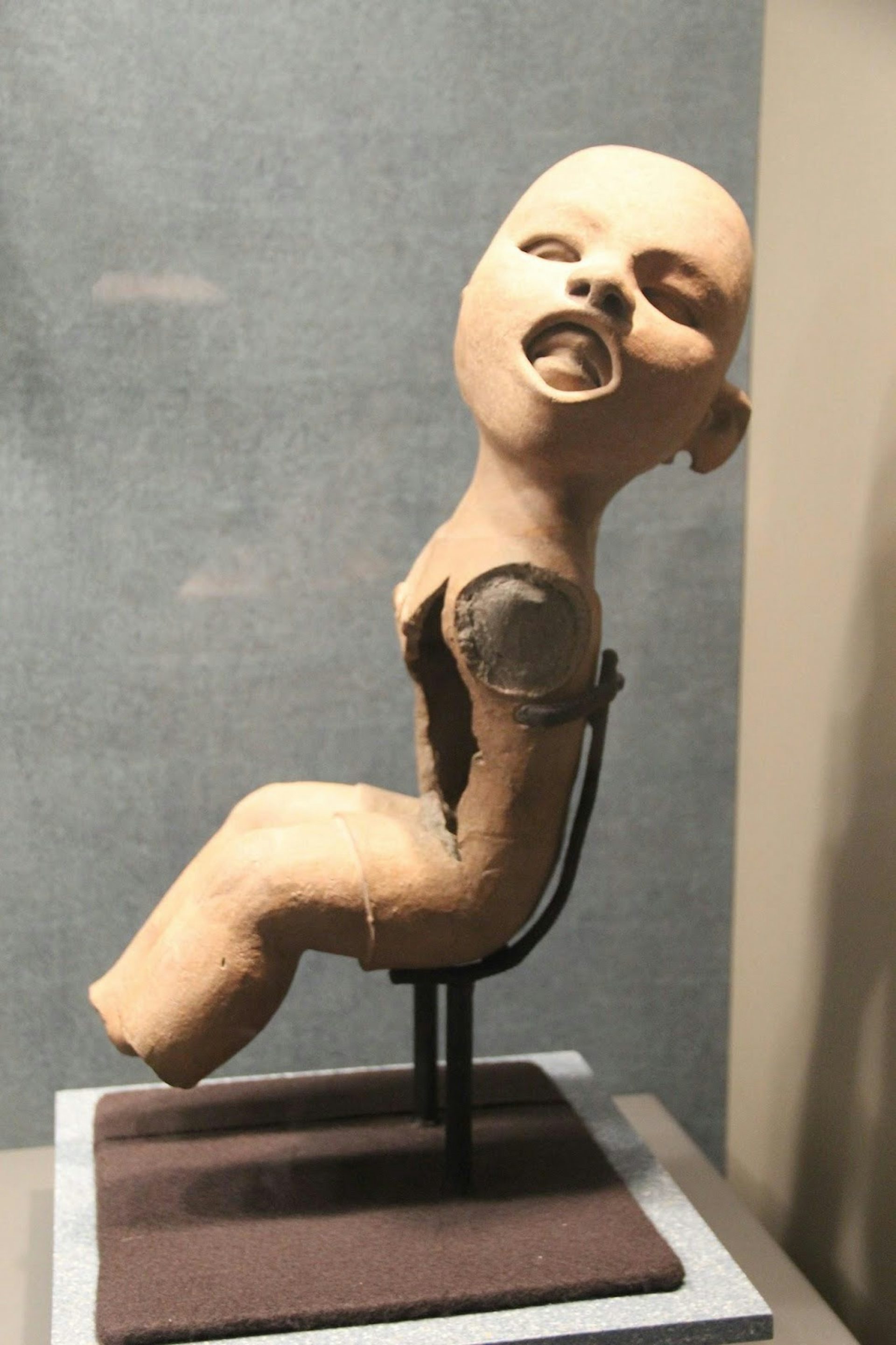

Double lips and eye sockets were prominent features in sculptures of Xipe Totec, a result of the skin mask he often wore.[5]

The double lips and eye sockets of this sculpture (c. 300-900 CE) suggest a figure wearing the flayed skin of a sacrificial victim. This piece was unearthed near Veracruz, Mexico.

Gary ToddPublic DomainFamily

Xipe Totec was the eldest child of the primordial gods Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl. His younger brothers were the Aztec creator gods Tezcatlipoca (omnipresent god of the night sky and knower of all thoughts), Quetzalcoatl (the god of the wind, giver of maize, and inventor of books and calendars), and Huitzilopochtli (the god of war and patron of the Mexica people).

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

Siblings

Brothers

Mythology

While stories of sacrifice were a common element in many religions, the Aztecs took this element a step further by engaging in a multitude of sacrificial rituals. Xipe Totec was but one of the gods that the Aztecs sought to appease through human sacrifice. Such offerings to the god of agriculture ensured that the rains would help the crops grow into a bountiful harvest.

Night Drinker

One of Xipe Totec’s many names was Yoalli Tlauana, or “night drinker.” This name may have referred to the seasonal nightly rains that were needed for the Aztec’s crops success.

Another interpretation suggested that the word used for drink, tlauana means to “drink to slight intoxication.” Aztec priests were occasionally known to become intoxicated for certain rituals, and this practice advanced the theory that the name “bears some relation to the celebration of [Xipe Totec’s] rites at night.”[6]

Patron of Goldsmiths

One unique feature of Xipe Totec was his status as the patron god of goldsmiths. The Aztecs believed gold to be sacred, and reserved it for ritual or state use. The Nahuatl word for gold, teocuitatl, translates as “excrement of the gods." While it may sound amusing to the modern ear, the Aztecs took the divine status of this excrement very seriously.

Stealing gold was an affront to the gods in general, and Xipe Totec in particular. Anyone caught committing this crime was imprisoned until Xipe Totec’s annual festival arrived, and was skinned alive during the festivities.[7]

Gold was one of the primary goods delivered to the Aztec Empire as tribute from its vassal states. One of the sites where gold was extracted was called “place of the terrible god Xipe Totec.” For the most part, Aztec gold was gathered through panning; the collected gold dust was then stored in hollow gourds. These gourds were in turn used as a unit of measurement to describe the amount of tribute the Aztecs demanded.[8]

The Festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli

The Aztec calendar, Xiuhpōhualli, was divided into eighteen 20-day months. The month known as Tlacaxipehualiztli, which was dedicated to Xipe Totec, saw many ritual gladiatorial sacrifices take place in honor of the Flayed One.

In such rituals, prisoners of war were tied to an obsidian obelisk and forced to battle against Aztec warriors. The prisoners stood little chance of victory, as the warriors they faced were armed with macuahuitl, wooden swords edged with obsidian blades. The prisoners themselves were armed with macuahuitl edged with feathers.[9]

The obsidian blades of a macuahuitl could be sharper than surgical steel. While no pre-conquest macuahuitl exist today, this recreation demonstrates what a ceremonial macuahuitl would have looked like.

Niveque StormCC BY-SA 3.0Other sacrificial victims were shot to death with arrows; the outpouring of blood was meant to symbolize the rain the Aztecs desired for their crops. The victims' hearts and skin would be removed after the rituals were complete. Priests and young men pledged to Xipe Totec wore the victims' skins as cloaks until these garments had either rotted way or a month had elapsed. Afterwards, the skins were buried at Xipe Totec’s temple.[10]

The apparent fascination with skins was related to Xipe Totec’s role as a fertility god. The Aztecs understood that snakes and maize shed their respective skins as a natural part of their life cycle. That Xipe Totec and his followers wore skins suggested that each of them was a vital force ready to emerge from an apparently dead husk.[11]

Pop Culture

In the mobile role playing game Brave Frontier, Xipe Totec appeared as a playable 1,000 year old ent.

Issue 5 of Grant Morrison’s 1995 comic book series The Invisibles featured a character claiming to be Xipe Totec. Like the Xipe Totec of Aztec tradition, the character wore a man's face as a mask.

The Friendly Atheist blog used Xipe Totec and his grisly proclivity for having people flayed as an example while discussing history’s tendency to forget about gods from defunct religions.