Ometeotl

Overview

In Aztec mythology, Ōmeteōtl was a binary god comprised of the husband and wife duo Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl who was responsible for the creation of the universe. The Aztecs believed that—prior to Ometeotl creating themselves—the universe was unknowable, and for all intents and purposes did not exist. Residing in the thirteenth and highest heaven, Ometeotl existed outside of human influence and rarely interacted with other deities.

This illustration from the Borgia Codex provides a typical representation of Tonacatecuhtli (an alternative spelling of Ometecuhtli).

FAMSIPublic DomainThere has been debate amongst scholars about the nature of Ometeotl. Some have argued that they represented a dual god, while others contended this was a misinterpretation foisted upon the Aztec by historians reading a deific multiplicity, similar to the Holy Trinity, onto translated texts.

Etymology

In Nahuatl (the Aztec language), “Ome Teotle” literally meant dual god or “Lord of Duality.”[1]

Because the name “Ometeotl” did not appear in primary documents, some questioned whether Ometeotl truly existed at all. The historian Richard Haly argued that Ometeotl was, in fact, the creation of Miguel Leon-Portilla’s 1956 work La Filosofia Nahuatl. While Ometeotl was not mentioned by name, references to dual creator gods appeared frequently throughout primary source documents. These documents demonstrated that the Toltecs—precursors to the Aztecs—worshipped a supreme binary deity as well. Though the name “Ometeotl” may have been anachronistic, available evidence nevertheless overwhelmingly supported the existence of the binary Aztec creator god.[2]

The gods that made up Ometeotl were Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl (literally: “two lord” and “two lady”).[3] In Aztec sources, the binary gods were referred to as Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl. Tonacacihuatl’s name held the same meaning as her husband’s, though the “cihuatl” suffix translated to “Lady of” instead of “Lord of.”

Depending on the translation, Tonacatecuhtli could be interpreted to mean “Lord of Our Food,” “Lord of Our Existence,” “Lord of Our Flesh,” “Lord of Our Sustenance” or “Lord of Abundance.” All of these titles referred to Tonacatecuhtli’s role as the progenitor of the Aztec pantheon, and thus as progenitor of all things.

This dualistic sculpture with a partially exposed skull is believed to symbolize life and death and was once thought to be a representation of Tonacatecuhtli. It is now thought to represent the two temples of Templo Mayor.

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0One alternative translation swapped “dual” (Ome) for “bone” (Omi) rendering Ōmeteōtl as “Bone Lord.” This interpretation of the name rejected the dual god concept in favor of a god who created things from bone.

Family

Both the binary god Ometeotl and the paired individuals Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl had no parentage, having each created themselves.

Ometeotl bore four sons, all of whom would be central figures in the Aztec pantheon:

Xipe Totec: the god of agriculture, rebirth, and goldsmiths.

Tezcatlipoca: the omnipresent god of the night sky and knower of all thoughts.

Quetzalcoatl: the god of the wind, giver of maize, and inventor of books and calendars.

Huītzilōpōchtli: the god of warfare and protector against the infinite night.

Family Tree

Mythology

Ometeotl was unique amongst the Aztec gods in that no temples were ever erected to them. After creating themselves and bearing children, their role in Aztec mythology was minimal. Though their children were four of the most significant gods in the entire Aztec pantheon, these gods operated independently of Ometeotl’s influence. While the Aztecs believed Ometeotl to be immensely important due to their role as creator of the universe, the Aztecs also thought Ometeotl laid beyond the reach of human influence. Accordingly, they did not build temples or offer sacrifices to Ometeotl.

Origins

According to the Codex Ramirez, a Spanish compilation based on Nahuatl works from the 16th century, Ometeotl “created themselves, and were perpetual inhabitants of the thirteenth heaven; of whose creation and beginning likewise there is nothing known except the fact that it also originated in the thirteenth heaven.”[4] The thirteenth heaven, or Ilhuicatl-Omeyocan, was the highest level of heaven and was reserved exclusively for Ometeotl—hence its inscrutable nature. Omeyocan took its name—meaning “the place of duality”—from the binary god who resided there.[5]

Ometeotl’s first notable action in the Aztec mythos was to bear four children. While their first three children were born complete, Ometeotl’s final son, Huitzilopochtli, “was born without flesh (nacio sin carne), but only bones” and would remain in this state for 600 years.[6] During this time, the other gods simply waited for Huitzilopochtli to become whole; they could not create the world without him. While Ometeotl’s children soon began to establish the laws of the universe, Ometeotl took no part in this process; indeed, they would take no action at all until 2,028 years had passed.

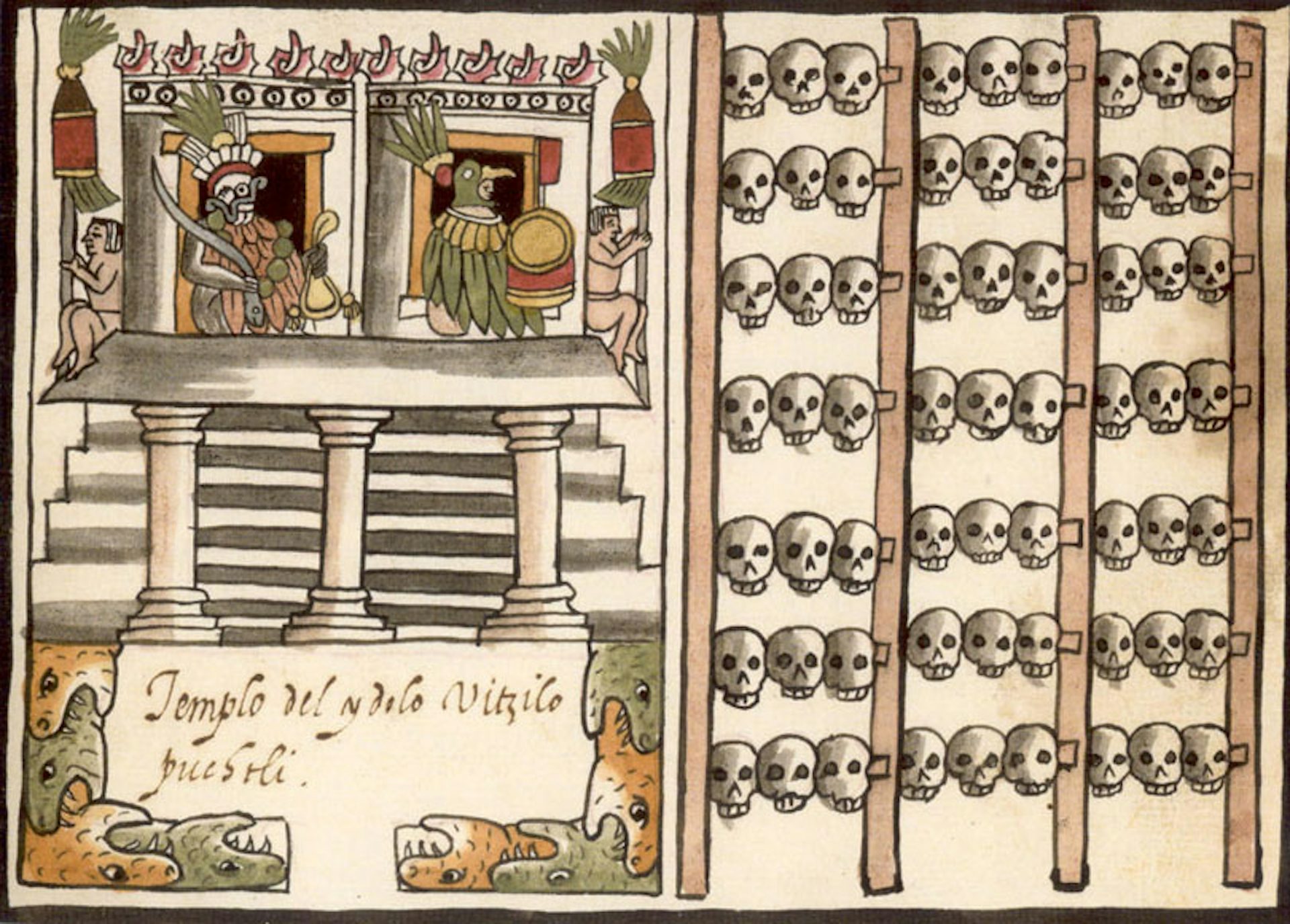

An excerpt from Tovar Codex (c. 1492-1600). Like the Codex Ramirez, the Tovar Codex provides a description of Aztec history. Ometeotl’s son Huitzilopochtli can be seen on the right edge of the temple scene. The image on the right of the page is a tzompantli, or Aztec skull rack.

John Carter Brown LibraryPublic DomainThe Five Suns

In the interceding millennia, Ometeotl’s sons each took their turns serving as the sun. Over time, each fell and was replaced by the next. When the final sun fell, it resulted in a torrential deluge that brought the heavens down with it.

In order to put the heavens back in place, Ometeotl’s sons created four people (some myths claim that they were Quetzacoatl’s followers, resurrected from bones stolen from the underworld) and with their help managed to return the heavens to their lofty abode. In a rare intervention, Ometecuhtli rewarded his sons by making them “lords of heaven and the stars.”[7]

Afterwards, a fifth and final sun was created. The Aztecs believed that this sun had to be sustained via human sacrifices and protected from evil beings known as the Tzitzimimeh.

The Origin of Tzitzimimeh

While Ometeotl was notable for doing very little that would come to influence human affairs, the Codex Ramirez said that Ometeotl created the Tzitzimimeh as “guardians of the skies, and she [the Tzitzimimeh] never is seen because she is on the road that the heavens make.”[8] This passage referred to the fact that the Tzitzimimeh were associated with stars that could only be seen during solar eclipses.

A depiction of a Tzitzimitl found in the Codex Magliabechiano. Mid-16th century.

Codex MagliabechianoPublic DomainThe Aztecs believed that these stars were attacking the sun, and that without human sacrifices there was a chance the sun would “never more be rekindled, but on that very night the human race would come to an end, and darkness eternal would reign over all; no sun should ever appear again, but the Tzitzimimes, [sic] fearful demons, would descend and eat up all mankind.”[9] Whether the Aztecs thought that Ometeotl’s creation defied their whims or simply regarded the god’s actions as inscrutable is unclear.