Thanatos

Thanatos I by Jacek Malczewski (1898)

National Museum, PoznańPublic DomainOverview

Pitiless Thanatos was the personification of death. He and his twin brother Hypnos, the personification of sleep, were children of Nyx, the ancient goddess of night. Thanatos represented the inexorable fate of all mortal beings. In literature and art, he was sometimes depicted leading the deceased to the Underworld.

On a few occasions, mortals did manage to get the better of Thanatos: Heracles, for example, overpowered him to save the life of Alcestis, the wife of his friend Admetus, while Sisyphus outwitted him (or bound him) to save his own life. Even so, Thanatos could only be delayed at best; he always triumphed in the end. Feared, dreaded, and even hated, Thanatos did not have a cult of his own.

Etymology

The name “Thanatos” (Greek Θάνατος, translit. Thánatos), appropriately enough, is the Greek word for “death” and is related to verbs such as θνῄσκω (thnḗ(i)skō), meaning “to die.” It is thought to derive from the Indo-European *dʰ(u)enh₂-, also meaning “to die.”[1]

Thanatos’ Roman counterpart was called Mors or Letum (Latin words for “death”).

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Thanatos Θάνατος (Thánatos) Phonetic

IPA

[THAN-uh-tos] /ˈθæn əˌtɒs/

Attributes

Functions and Characteristics

Thanatos was the Greek god or daemon who personified death. A deity without a cult, he was usually met with dread or even hatred. The poet Hesiod described him as having

a heart of iron, and his spirit within him is pitiless as bronze: whomever of men he has once seized he holds fast: and he is hateful even to the deathless gods.[2]

Ever relentless, Thanatos always claimed his prize in the end. He could not be swayed by gifts or speeches.[3]

Occasionally, Thanatos was viewed in a more optimistic light, as a gentle liberator and giver of eternal sleep to weary souls.[4]

Thanatos lived together with his twin brother Hypnos (“Sleep”) beyond the edge of the earth, in the murky Underworld home of their mother Nyx (“Night”).

In literature and art, Thanatos was sometimes represented carrying away the deceased or bringing them to the Underworld. But his exact purpose and function is unclear, as it was more often the god Hermes who was considered responsible for bringing souls to the Underworld, while Hades was the ruler of the dead. Thanatos seems to have been above all a symbolic entity, representing the inexorable approach of death.

Iconography

Thanatos appeared in ancient art from an early period. He seems to have been especially prominent in Classical Athenian vase painting. In the beginning, he was usually depicted as a winged young man in the company of his twin brother Hypnos; but over time, Thanatos took on a more frightful appearance, with shaggy hair and beard and a hooked nose.

Especially popular among artists was the scene from the Iliad in which Thanatos and Hypnos were sent by Zeus to carry the body of the hero Sarpedon from the battlefield. One of the most famous of all Athenian vases, the so-called “Euphornios Krater,” depicts this scene. But Thanatos was also represented as the escort of other deceased heroes or mortals.

The so-called “Euphronios Krater,” an Attic red-figure calyx-krater signed by Euxitheos (potter) and Euphronios (painter) showing Hypnos (left) and Thanatos (right) carrying away the body of Sarpedon (center bottom) as Hermes (center top) presides

National Museum, Cerveteri / Jaime Ardiles-ArcePublic DomainThanatos could be found in other visual arts as well. For instance, there were statues of him and his brother Hypnos in the citadel of Sparta.[5] Thanatos and Hypnos were also featured on the famous ornamental Cypselus Chest, where the two gods were shown as children sleeping in the arms of their mother Nyx.[6]

The Romans generally avoided depicting the personified god of death, presumably due to superstition. Over time, depictions of Thanatos became rarer among the Greeks as well.[7]

Family

Thanatos was the son of Nyx, the primordial goddess of the night. In the most familiar account, known from Hesiod’s Theogony, Thanatos was one of several children of Nyx born without a father, who collectively represented various dark and evil forces. Thanatos’ siblings thus included Momos (“Blame”), Eris (“Strife”), and the Moirae (“Fates”), among many others. Thanatos also had a twin brother, Hypnos, the personification of sleep.[8]

There were other versions of Thanatos’ genealogy as well. According to Hyginus, he was born not to Nyx alone but rather to Nyx and her consort Erebus, the embodiment of darkness.[9] Alternatively, Thanatos was sometimes said to have been the child of Gaia and Tartarus,[10] or of the obscure goddess Astraea.[11]

Mythology

Thanatos played a limited role in Greek mythology. He was sometimes sent by the gods to carry away the body of a mortal who had died. In one famous scene from Homer’s Iliad, for example, Zeus dispatched Thanatos and his twin brother Hypnos (“Sleep”) to carry his son Sarpedon off the battlefield during the Trojan War. Thanatos and Hypnos sped to the body and spirited it away to Sarpedon’s home in Lycia for a proper burial.[12]

In a few memorable myths, Thanatos found himself bested by mortals. Sisyphus, the king of Corinth, was even so bold as to bind Thanatos in chains when he came to take him to the Underworld. Sisyphus was thus able to escape death for a time. But his actions led to a dangerous crisis: with Thanatos in chains, death had been—temporarily—abolished.

The gods finally sent Ares, the god of war, to release Thanatos from his chains. Sisyphus was forced to die, but he managed to trick the Underworld gods a second time. He told his wife not to bury him with the proper rites; after descending to the Underworld, he then convinced the gods of death to let him return to the world above so as to discipline his wife. Once restored to the land of the living, of course, Sisyphus did not return to the Underworld. But death did eventually get its hands on Sisyphus, and once the king was back in the Underworld for good, he was sent to suffer in Tartarus for all eternity.[13]

Another myth told of how Heracles beat Thanatos. It all began when Apollo devised a way for his mortal friend Admetus, the king of the northern Greek town of Pherae, to escape death: if Admetus found somebody willing to die in his place, he could go on living. Admetus’ wife Alcestis nobly volunteered to die for her husband. But when Thanatos came to collect Alcestis, another one of Admetus’ powerful friends, the strongman Heracles, stood in his way. Heracles managed to fight Thanatos off and thus rescued Alcestis.[14]

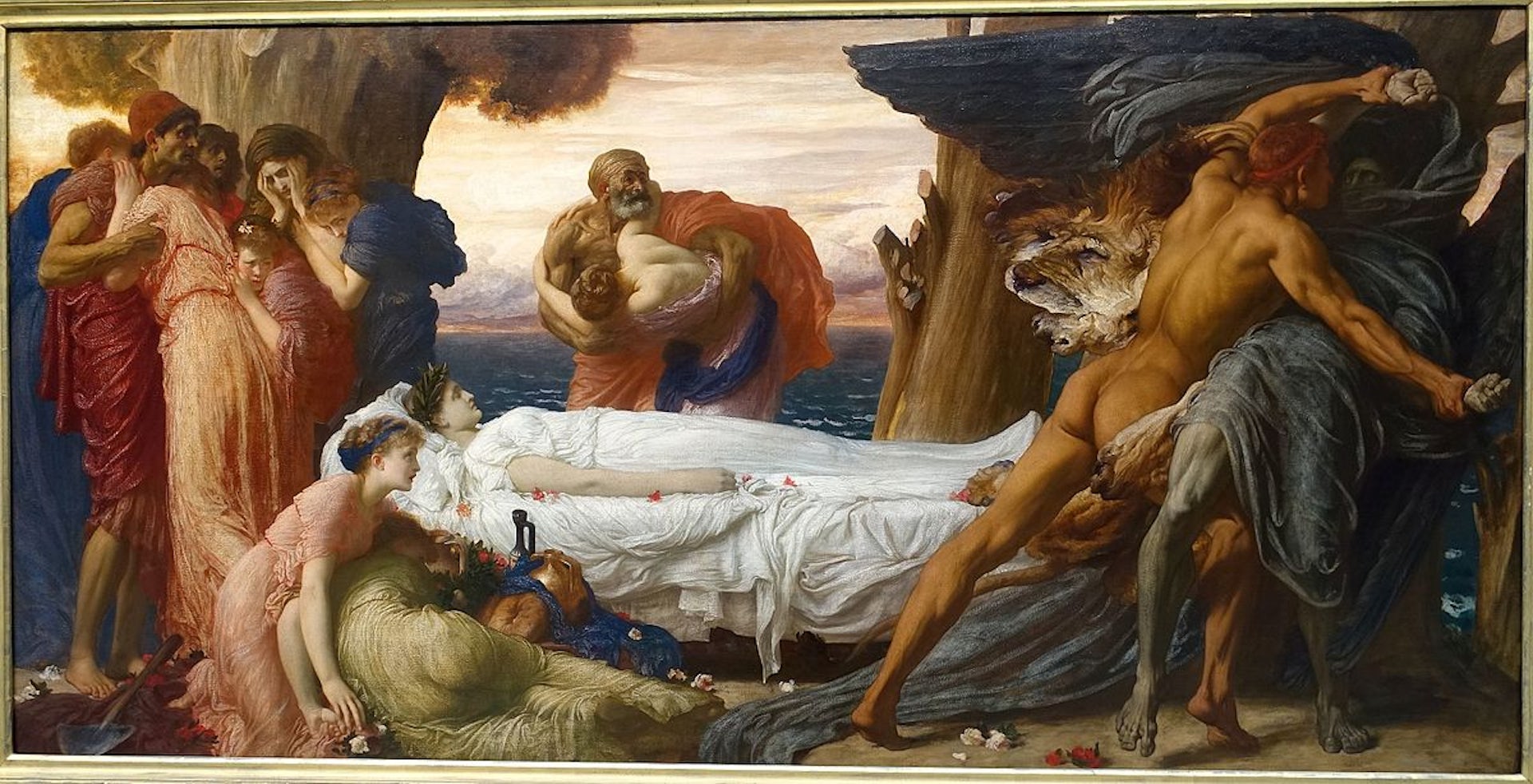

Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis by Frederic Lord Leighton (ca. 1869–1871)

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT / DaderotPublic DomainPop Culture

Thanatos continues to influence personified representations of death—though the figure of Death in contemporary pop culture is a far grimmer character, with his dark cowl and scythe. The Thanatos of Greek mythology is still sometimes remembered: for example, two of the main characters in Neil Gaiman’s graphic novel The Sandman, Dream and Death, are reworkings of the Greek twins Hypnos and Thanatos.

Thanatos has been prominent in the realms of psychology and medicine as well. Sigmund Freud famously wrote about the death drive, “Thanatos,” which he opposed to the life drive, “Eros.” Thanatos also lives on in such terms as “thanatology” and “euthanasia.”