Sisyphus

Overview

Sisyphus was a Greek king usually associated with Corinth. He was famously cunning, but unfortunately also deceitful and impious. In the most common version of the myth, Sisyphus managed to cheat Death and thereby extend his life (the details of how he accomplished this vary across different sources).

Eventually, however, Sisyphus did die. For acting against the will of the gods, Sisyphus received a terrible punishment in the afterlife: he was sent to Tartarus, roughly the Greek equivalent of hell, where he was forced to roll a giant boulder up a hill, only for it to roll back down once he reached the top. Sisyphus was thus forced to endlessly repeat the same grueling task for all eternity.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Sisyphus” (Greek Σίσυφος, translit. Sisyphos) is uncertain. In 1906, German scholar Otto Gruppe suggested that it was derived from the Greek word sisys, meaning “goatskin”—a reference, supposedly, to a rain-charm that employed goatskins.[1] More recently, other scholars have suggested some connection with the Greek word sophos, meaning “clever” or “wise.”[2]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Sisyphus Σίσυφος (translit. Sisyphos) Phonetic

IPA

[SIS-uh-fuhs] /ˈsɪs ə fəs/

Titles and Epithets

Sisyphus only appears occasionally in surviving ancient literature and therefore only has a few epithets. He was sometimes referred to as “Aeolides,” meaning “son of Aeolus”—a reference to his father, the Thessalian king Aeolus. But Sisyphus’ most common epithets evoked his craftiness through such Greek words as kerdiōn and aiolomētēs (meaning simply “crafty”).

Attributes and Iconography

Sisyphus’ chief personal attribute was his cunning. In the Iliad, he is described as the “craftiest of men,”[3] while the poet Pindar wrote that he was “like a god…very shrewd in his devising.”[4]

But Sisyphus also had a tendency to overstep his mortal bounds and offend the gods, which caused him no end of trouble. In the end, his most famous attribute was not an aspect of his personality at all but rather the punishment for which he will always be remembered: the huge stone that he was forced to roll up a hill in Tartarus for all eternity.

In ancient art, Sisyphus was most commonly represented with his stone in Tartarus.[5]

Family

Sisyphus was the son of Aeolus, an early king of Thessaly, and his queen Enarete. His brothers included Cretheus, Athamas, Salmoneus, and Perieres,[6] as well as Deion and Magnes (in some sources).[7] His sisters included Canace, Alcyone, Pisidice, Calyce, and Perimede. In some traditions, however, Sisyphus’ siblings shared their names with Greek cities and towns, including Mimas,[8] Tanagra,[9] and Arne[10]—which, according to local myths, had been named after them.

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

- Aeolus (son of Hellen)

- Enarete

Siblings

Brothers

Sisters

- Athamas

- Cretheus

- Deion

- Magnes

- Perieres

- Salmoneus

- Alcyone

- Canace

- Calyce

- Perimide

- Pisidice

Consorts

Wife

Lovers

- Merope

- Anticlea

- Medea

Children

Sons

- Almus

- Glaucus (son of Sisyphus)

- Odysseus

- Ornytion

- Porphyrion

- Sinon

- Thersander

Mythology

King of Corinth

Sisyphus was usually described as the king of Ephyra (the original name of Corinth).[15] He was sometimes said to have actually founded the city.[16] But in other traditions, Medea made Sisyphus king of Corinth after she killed the city’s royal family.[17]

Crime and Punishment: Three Versions of Sisyphus

In antiquity (as is still the case today), Sisyphus served as a cautionary tale for the terrible consequences of offending the gods. In the Odyssey, Odysseus describes seeing Sisyphus pushing his stone in the Underworld:

Verily he would brace himself with hands and feet, and thrust the stone toward the crest of a hill, but as often as he was about to heave it over the top, the weight would turn it back, and then down again to the plain would come rolling the ruthless stone. But he would strain again and thrust it back, and the sweat flowed down from his limbs, and dust rose up from his head.[18]

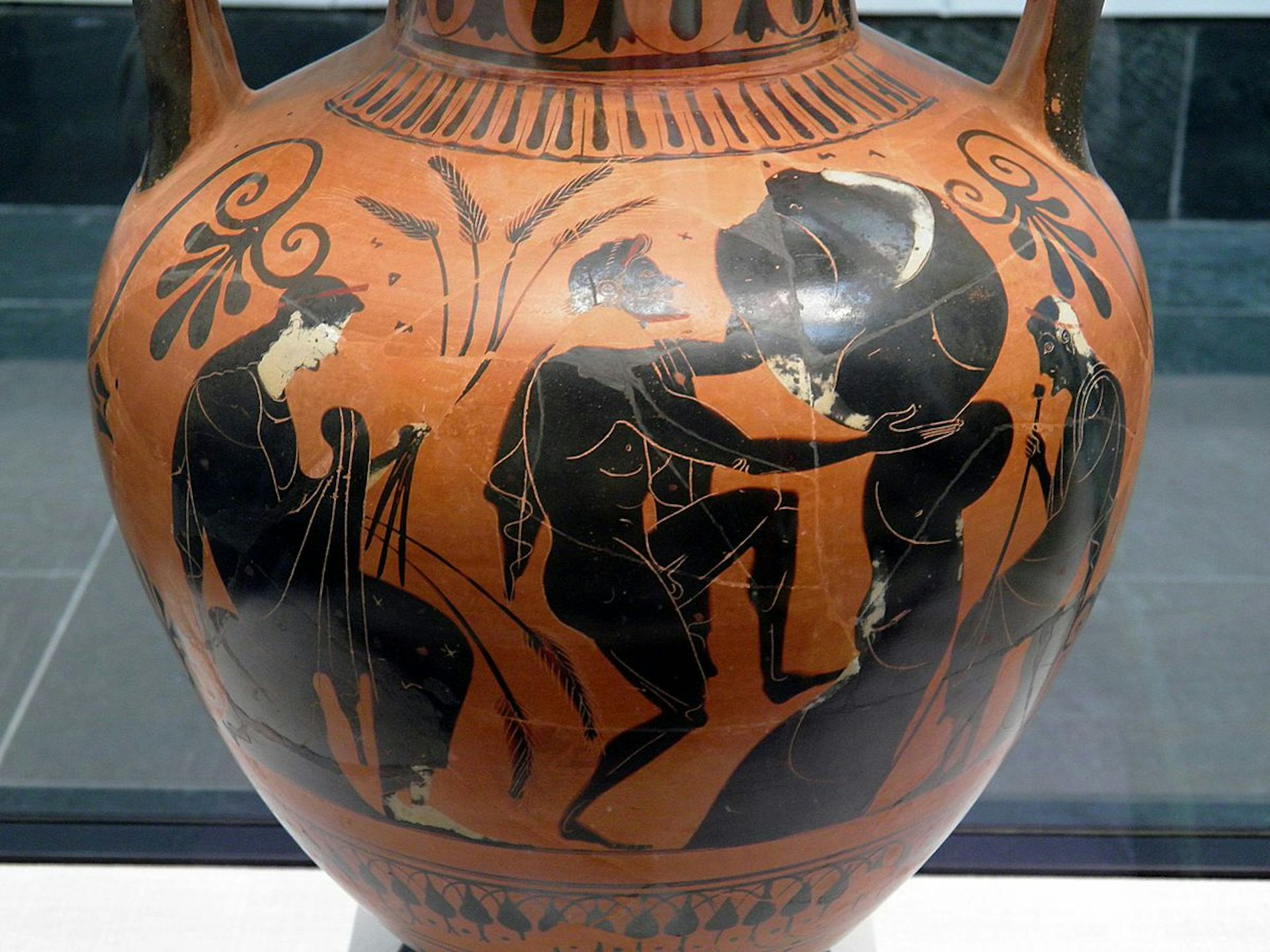

Attic black-figure amphora showing the punishment of Sisyphus in the Underworld. Attributed to the Acheloos Painter (ca. 525–500 BCE). Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich, Germany.

Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0But there were different accounts of the crime that so memorably provoked the gods’ wrath.

Two Ways to Cheat Death

In what has become the most familiar tradition, Sisyphus was punished because he cheated Death. The most complete account of this myth comes from a summary of the story as it would have been told in the lost writings of Pherecydes, a genealogist and mythographer of the fifth century BCE.

According to Pherecydes, it all started when Sisyphus revealed to the river god Asopus that he had seen Zeus carrying off Aegina, Asopus’ daughter. In revenge, Zeus sent Death to take Sisyphus to the Underworld. But Sisyphus managed to chain Death. Because of this, all humans (not just Sisyphus) were temporarily spared from death—at least until Zeus sent Ares to set things right.

After Death had been freed, he seized Sisyphus and took him to the Underworld—but not before Sisyphus instructed his wife Merope not to perform the customary funerary rituals for him. When Sisyphus reached the Underworld, he convinced Hades (or Hades’ queen Persephone, in some versions) to let him return to the world of the living to punish his wife for neglecting his funeral. Once back, of course, he did not return to the Underworld.

Eventually, however, Sisyphus died of old age. Once he was back in the Underworld for good, the gods punished his all-too-brief victory over death by forcing him to forever push a stone up a hill.[19]

Asopus, Aegina, and Zeus

Several well-known authors—among them the geographer Pausanias and the mythographer Apollodorus—simplified the myth of Sisyphus by excluding his attempts to cheat Death. As in Pherecydes’ account, Sisyphus told Asopus that Zeus had carried off Aegina. In exchange for this information, some said, Sisyphus was given a spring on the Acrocorinth. But the gift, however grand, was little consolation in the end: in this version, Sisyphus received his eternal punishment solely for betraying Zeus’ secret.[20]

This myth follows a pattern seen elsewhere in Greek mythology, in which a god disproportionately punishes someone for revealing their secrets. Other examples include Battus, transformed into a stone by Hermes after he disclosed that the infant god had stolen Apollo’s cattle, or Ascalaphus, buried alive by Demeter after he testified that Persephone had tasted food in the Underworld (which forced her to forever remain Hades’ wife). The version of Sisyphus described by Pausanias and Apollodorus thus joins the ranks of other ill-fated mythological tattletales.

Sibling Rivalry: Sisyphus vs. Salmoneus

In another tradition, recorded by the Roman mythographer known as Hyginus,[21] Sisyphus was locked in a bitter conflict with his brother Salmoneus. The hatred between them was so deep that Sisyphus went to the oracle of Delphi to learn how he might kill Salmoneus. The oracle told him that if he had children with Salmoneus’ wife Tyro, they would do the deed for him.

Sisyphus followed the oracle’s advice and bore two sons with Tyro. But when Tyro learned the prophecy, she killed the children. Tantalizingly, the text breaks off precisely where it would have described what Sisyphus did next: presumably, he took a cruel revenge on Tyro. Whatever the exact details, Sisyphus’ actions were apparently savage enough to earn him his famous punishment.[22]

Other Myths

Sisyphus features in a handful of other myths.

In some traditions, Sisyphus was tangentially involved in the sad myth of Ino. After Hera drove Ino mad enough to drown herself and her son Melicertes, Sisyphus found Melicertes’ body washed up on the shore of Corinth. He buried the body and founded the Isthmian Games, athletic and artistic contests held every two years in honor of the boy.[23]

Another myth pitted Sisyphus against Autolycus, also a famous mythological trickster. Autolycus, a son of Hermes, was a skillful thief—almost impossible to catch. But Sisyphus found a way to outsmart him. Autolycus stole from Sisyphus’ herd, and true to form, he disguised the crime almost perfectly, slipping the animals away undetected and even changing their appearance. But Sisyphus had marked the bottoms of his animals’ hooves and so was able to prove Autolycus’ crime.[24]

Pop Culture

The most well-known modern adaptation of Sisyphus is Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), an essay on the philosophy of the absurd.

Sisyphus has also appeared in cinema and television, including the 1990s television series Xena: Warrior Princess and Hercules: The Legendary Journeys. More recently, Sisyphus inspired the Korean series Sisyphus: The Myth (2021).