Orion

Diana Accepts the Huntsman Orion into her Company by Etienne Delaune (1540–1583)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Orion is best remembered as a mighty hunter. However, there is no standard version of his mythos: many different tales were told about Orion, and more often than not these myths contradicted each other.

Virtually all traditions agree that Orion was a mortal hunter of extraordinary size, strength, and skill, and that he later became the constellation still known as Orion. All further details—his family, birth, homeland, death, and so on—diverge widely across ancient sources.

One of Orion’s most important characteristics was his lustfulness. He had many lovers (fathering fifty sons by as many nymphs) and pursued many others still. In one tradition, he raped the daughter of the Chian king Oenopion, who then put out Orion’s eyes in a rage. Orion was forced to travel to the Far East to regain his eyesight.

In other traditions, Orion even made amorous advances toward Artemis herself, the virgin goddess of the wild and of hunters. Some said that Orion’s love for Artemis was what led to his death, though in other accounts it was Gaia, the primordial goddess of the earth, who had Orion killed.

Following his death, Orion was put in the sky as a constellation—a reward, it seems, for his bravery and strength. Though he was an important figure in early Greek mythology, Orion was later eclipsed by other, similar mythical figures, such as Heracles.

Some traditions connected Orion to Crete or even Sicily, but he was most often said to have been Boeotian in origin. Indeed, the Boeotians worshipped him as a hero.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Orion” (Greek Ὠρίων, translit. Ōríōn) is obscure. The ancient Greeks sometimes claimed that it came from the verb οὐρέω (ouréō), meaning “to urinate, ejaculate”—an etymology connected to one of the myths of how Orion was born (see below). But this is likely no more than a folk etymology.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Orion Ὠρίων (Ōríōn) Phonetic

IPA

[uh-RAHY-uhn] /əˈraɪ ən/

Alternative Names

In the ancient sources that claimed Orion’s name was derived from οὐρέω (ouréō, “to urinate, ejaculate”), some added that this name was later changed for the sake of propriety.[1]

According to one author, Orion was sometimes also called Candaon (Greek Κανδάων, translit. Kandáōn) by the people of Boeotia—a name he shared with an obscure god worshipped by the Greeks’ northern neighbors. This name may have meant something like “dog strangler.”[2]

Attributes

Locales

Orion was usually associated with the region of Boeotia in central Greece. His homeland was most often named as Tanagra, in the southernmost corner of the region,[3] though some said that he was born in a town called Hyria (itself regarded as part of either Tanagra or nearby Thebes).[4] Others said that Orion was from Euboea, the large island separated from Boeotia by a narrow strait.[5]

But this was not the only tradition concerning Orion’s homeland, nor perhaps even the original one. In the earliest known sources on Orion, he was connected instead with Crete, a major island in the Aegean Sea; his mother, it was said, was one of the daughters of the Cretan king Minos. Other traditions linked Orion with lands even further away, including the island of Sicily.[6]

Appearance and Abilities

Orion was described as a powerful hunter of incredible size.[7] But he was not just a large brute: he was also said to have been astonishingly handsome.[8] Orion could be recognized by the weapons he carried: a great sword and a bronze club.[9] In Book 11 of the Odyssey, the hero Odysseus claims to have marveled at Orion—and his arms—during his visit to the Underworld:

I marked huge Orion driving together over the field of asphodel wild beasts which he himself had slain on the lonely hills, and in his hands he held a club all of bronze, ever unbroken…

In addition to his strength and ability as a hunter, Orion was also granted the ability to walk on water.[10] But this may have simply meant that Orion was so tall that he could wade through the sea without being fully submerged. The Roman poet Virgil, for instance, writes of

tall Orion stalking o'er the flood.

(When with his brawny breast he cuts the waves,

His shoulders scarce the topmost billow laves)[11]

One early source added another skill to Orion’s already impressive list of powers, stating that Orion had inherited the gift of prophecy from his male ancestors.[12]

Constellation

Orion was known as a constellation from a very early period,[13] having been placed in the heavens after he died. This constellation was thought to pursue the Pleiades (a star cluster) across the sky, a celestial phenomenon that inspired further myths about Orion.[14] Another constellation—Sirius, or the “Dog Star”—was regarded as Orion’s dog.[15]

As a constellation, Orion—ever the hunter—was said to be in constant pursuit of the constellation Lepus, the hare. But some sources, deeming a hare unworthy of Orion’s talents, instead claimed he was chasing Taurus, the bull.[16]

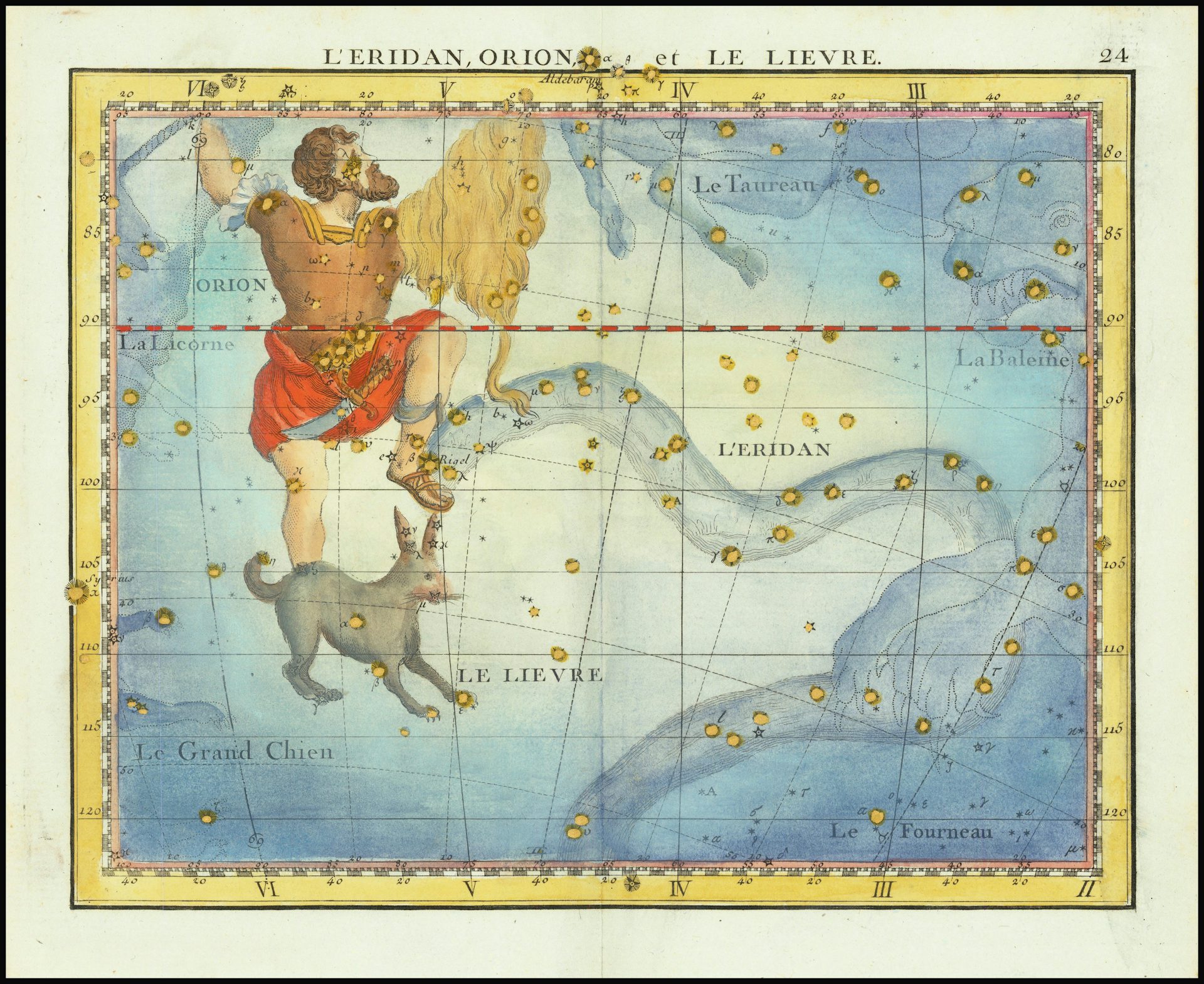

Eridanus, Orion, and Lepus by John Flamsteed (1776)

Jean Nicolas Fortin, Atlas Celeste de ForsteedPublic DomainIconography

When Orion appeared in ancient art, he was always depicted in full hunter regalia. Usually he would be shown carrying some kind of weapon, such as a club, a sword, or a lagobolon (a kind of missile used for hunting hares). He sometimes sported a hunter’s outfit (a short tunic and mantle), but more often he was shown nude.

It was not unheard of for artists to depict Orion as the opponent of Artemis, echoing many literary accounts of his myth. But he was most often represented as a constellation, eternally pursuing his quarry across the heavens.[17]

Family

There were several different versions of Orion’s parentage. In the earliest accounts, Orion was the son of the sea god Poseidon and a mortal woman named Euryale (herself a daughter of the Cretan king Minos).[18]

In another famous tradition, perhaps of somewhat later origin, Orion was born from a bullhide covered in the semen of the gods Zeus, Poseidon, and Hermes; he was then brought up by a Boeotian man named Hyrieus.[19] Other sources described Orion as “earth-born,” or a son of the earth goddess Gaia.[20]

Orion was a prolific lover. He had a wife named Side, about whom nothing is known except that she was cast into Hades for boasting that she rivaled the goddess Hera in beauty.[21] Orion also had many lovers, including Eos, the rosy goddess of dawn,[22] and a Chian girl named Merope.[23]

Orion’s various unions gave him many children. Two of his daughters, Metioche and Menippe (also known as the Coronides), sacrificed themselves to save Boeotia from a plague, after which they were worshipped in the region.[24] Another daughter of Orion’s, Menodice, was the mother of Hylas, a companion of Heracles who sailed with the Argonauts.[25]

In one tradition Orion was also the father of Mecionice, sometimes named as the mother of Euphemus—one of the Argonauts and an ancestor of the Battiads.[26]

To these daughters we may add some fifty sons whom Orion fathered with as many nymphs.[27] One of these sons was the prophet Acraephen, who gave his name to the town of Acraephia near the sanctuary of Apollo on Mount Ptois.[28] Another son of Orion, Dryas, helped defend Thebes against the invading army led by the “Seven against Thebes.”[29]

Mythology

Origins

The myth of Orion appears to have been very ancient; he may have emerged as a hunting hero as early as the Bronze Age. Orion has often been compared to shaman figures and larger-than-life heroes from other cultures, especially figures known for their extraordinary size, strength, and hunting prowess. Examples include the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh, the Ugaritic Aqhat, and the Celtic Cúchulainn.[30]

But the Greeks’ interest in Orion seems to have waned early on. Perhaps he was viewed as too primitive a hero amidst an influx of new technologies, including agriculture, writing, and organized warfare.

At any rate, many of Orion’s functions—as a hunter of wild beasts, a warrior, and so on—were assumed by other heroes (especially Heracles), who quickly eclipsed him in importance. This early loss of interest may explain why Orion’s myths were never “standardized” by any poets.

The strange patchwork quality of Orion’s mythology is reflected in accounts of his birth. In one tradition, the pious Boeotian Hyrieus had acted as a host to the gods Zeus, Poseidon, and Hermes; wishing to reward the man’s hospitality, the gods promised to grant him a single request. Hyrieus asked for a son.

The three gods promptly ejaculated on a bullhide, then buried the semen-covered scrap of leather in the earth. This was how Orion was born (and perhaps how he got his name, which can be translated as “the ejaculated one”).[31]

This eventually became the prevailing myth of Orion’s birth. But other traditions connected Orion with the royal family of Crete or with other genealogies (see above).

Orion, Oenopion, and Merope

Orion was notorious for his lecherous ways. In one story, he tried to force himself on the Pleiades (or their mother Pleione), who implored Zeus to help them escape. Zeus answered their prayer by turning them into stars—the star cluster still known today as the Pleiades.[32]

In another story, it was Eos, the goddess of the dawn, who pursued Orion, abducting the handsome hunter so that she could have her way with him.[33]

But the most notorious of Orion’s affairs was with Merope (sometimes called Aero), the daughter of King Oenopion of Chios. Orion had fallen in love with Merope and tried to win her hand.

In one version of the story, Oenopion promised to let Orion marry his daughter if the famous hunter cleared Chios of wild beasts—only to change his mind after Orion had already delivered on his end of the bargain. Eventually, the frustrated Orion broke into Merope’s chamber and raped her. Oenopion retaliated by putting out Orion’s eyes.

Orion, now blind, made his way to the island of Lemnos, where the smith god Hephaestus had his workshop. Hephaestus took pity on Orion and gave him his servant Cedalion as a guide. From astride Orion’s massive shoulders, Cedalion led his new master east, where Orion regained his vision when he looked upon the rays of the rising sun (others said it was the sun god Helios himself who healed him).

Orion then turned back to take revenge on Oenopion, who escaped by having his people hide him beneath the earth.[34]

Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun by Nicolas Poussin (1658)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOrion in Sicily

Another body of myths told of Orion’s adventures in Sicily. In one story, Orion was said to have helped Zanclus, the founder of the Sicilian city of Zancle (later known as Messina), to build the promontory that formed its harbor.[35]

Another story, seemingly very ancient, related that there was once a broad sea separating Sicily from the boot of Italy. It was Orion who built the headland, known as the Peloris (modern Punta del Faro), that extended along the northern part of the island. He then erected a temple to Poseidon on the very tip of the island and migrated east to Euboea.[36]

The Death of Orion

There were many different versions of how Orion died, some of them flatly contradicting one another. These traditions can be roughly divided into two groups.

In the first group of myths, Orion was killed by Artemis. But her motivation for killing him, as well as her method, varied across sources. In the earliest attested account, Orion was shot down by Artemis on Ortygia for reasons that are not entirely clear.[37]

Other authors elaborated on this story, begetting further variants. According to some, Orion tried to rape Artemis, who sent a giant scorpion to kill him[38] or else shot him down with her arrows.[39] According to others, Orion tried to rape not Artemis herself but rather Artemis’ handmaiden Upis, and it was for this reason that Artemis killed him.[40]

According to others still, Orion did not try to rape anyone but simply challenged Artemis to a discus contest[41] or mocked her abilities as a huntress[42]—displaying an insolence for which he could only pay with his life.

But in one account, Artemis actually fell in love with Orion and even wished to marry him, despite the fact that, until then, she had been firmly committing to remaining a virgin. This horrified Artemis’ twin brother Apollo, who decided to trick Artemis into killing her would-be ravisher.

Spotting Orion’s head one day as he was swimming in the sea, Apollo bet Artemis that she could not hit the distant speck with her arrow. Not one to miss an opportunity to show off, Artemis shot Orion straight through the head, not realizing what she was doing until it was too late.[43]

Diana Over Orion’s Corpse by Daniel Seiter (1658)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainIn another group of traditions, Orion was killed not by Artemis but by Gaia, the goddess of the earth (in these accounts, Orion was usually described as a friend and hunting companion of Artemis, rather than her enemy).

As the story goes, Orion foolishly boasted that no beast of the earth was a match for him. This evidently offended or provoked Gaia, who promptly brought forth a giant scorpion to disprove Orion’s claim.

After Orion was killed by the scorpion, Artemis and her mother Leto asked that he be placed in the stars (in some accounts, this was a reward for saving them from the terrible scorpion). Zeus agreed to their request, and Orion became a constellation.[44]

Worship

Orion was highly revered in Boeotia and had a famous tomb in Tanagra (near Mount Cerycius, modern-day Mount Tanagra).[45] The presence of a tomb suggests that Orion was likely worshipped as a hero in the region. He may have also been the recipient of hero cult elsewhere in Greece.

Popular Culture

Retold and reinterpreted by countless individuals over the centuries, the myth of Orion remains widely known today.

In contemporary literature, Orion has appeared in many different guises, some of them quite surprising and original. For twentieth-century authors such as René Char and Claude Simon, Orion served as a potent symbol of human life and of writing. In his Orion series, Ben Bova reimagined Orion as a servant of various gods, traveling through time.

Orion also appears in Rick Riordan’s The Heroes of Olympus series, where he is (mis)represented as one of the villainous Giants fighting against the Olympians.

Orion has likewise been an important figure in Western music, featuring in a number of operas from the seventeenth century and beyond. Most recently, he has appeared in compositions by Philip Glass, Tōru Takemitsu, Kaija Saariaho, and John Casken.