Hecate

Hecate, Procession to a Witches' Sabbath by Jusepe de Ribera (pre-1620).

Wellington Collection (Apsley House)Public DomainOverview

Hecate was a powerful goddess of uncertain origin. She was usually called the daughter of the Titans Asteria and Perses, but there were many alternate versions of her parentage, including some that made her a daughter of Zeus. Though Hecate was most commonly depicted as a sinister goddess of magic, witchcraft, and the Underworld, she was sometimes portrayed as kind and helpful. Like Athena and Artemis, she was considered a virgin goddess.

It is difficult to define Hecate. She does not appear in the Homeric epics and was most likely adopted into the Greek pantheon from the Carians of Asia Minor. What we do know is that she was virtually ubiquitous in ancient Greece, being at once the goddess of witches, the household, crossroads and travel, agriculture, and more.

Etymology

The name “Hecate” (Greek Ἑκάτη, translit. Hekatē) is the feminine form of hekatos, an epithet of the god Apollo meaning “the one who works from afar.” But the true etymology of the name is uncertain. Moreover, the fact that Hecate had a Greek name does not necessarily mean that her cult originated in Greece (she more likely emerged from Caria in Asia Minor).[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Hecate Ἑκάτη (translit. Hekatē) Phonetic

IPA

[HEK-uh-tee] /ˈhɛk ə ti/

Alternate Names

Hecate was often identified with a number of other goddesses (both Greek and non-Greek), including Artemis, Selene, Persephone, Crataeis, and Brimo. Consequently, “Hecate” could be seen as an alternate name for any one of these deities.

The Romans often referred to Hecate as Trivia (“she of the triple road”), echoing the goddess’s association with crossroads.

Titles and Epithets

Hecate possessed numerous (sometimes contradictory) epithets that reflected the many different sides of her nature.

As an Underworld goddess, Hecate was chthoniē (“chthonic, of the Underworld”); as a goddess of magic and witchcraft, she was nyktypolos (“she who wanders at night”) or skylakagetis (“leader of dogs”); as a goddess of crossroads, she was trioditis (“she of the triple road,” translated into Trivia by the Romans) and enodia (“she of the road”); and in her capacity as a helper to mortals, she was sōteira (“savior”), atalos (“tender”), kourotrophos (“nurse of the young”), or phōsphoros (“bringer of light”).

Attributes

Functions, Origins, and Transformations

The powerful Hecate ruled over many domains. By the fifth century BCE, she was above all a goddess of magic and witchcraft, but she also had associations with the Underworld, ghosts, the moon, various animals (especially dogs and creatures of the night), female initiation (including marriage and childbirth), agriculture, and entrances to public and private spaces (such as crossroads, doorways, and fortifications).

Hecate’s functions thus encompassed virtually every aspect of human life (and death). But the origins of this strange and mysterious goddess are unclear. Hecate probably originated as a Carian goddess who was adopted by the Greeks during the Archaic Period (ca. 800–480 BCE).

Hecate also changed considerably over time. Unknown to Homer, she first appeared in the seventh century BCE, in Hesiod’s Theogony, where she was very different from the Underworld goddess of witchcraft she eventually became. Hesiod praises Hecate at length as a goddess “whom Zeus the son of Cronos honored above all.”[2] Hesiod’s Hecate has a share of earth, sea, and sky (but not the Underworld) and provides aid to all mortals: kings, warriors, athletes, shepherds, fishermen, mothers, children, and so on.[3]

Hesiod’s Hecate seems almost unrecognizable in light of later developments. By the fifth century BCE, she had become a much darker, more menacing figure. Though she was still sometimes seen as kind or helpful (it was during this period that the poet Pindar described Hecate as a friendly virgin),[4] she had become primarily a goddess of witchcraft, the night, and the Underworld. How and why this shift occurred remains a mystery.

Iconography and Symbols

In her earliest representations, Hecate looked like any other goddess, shown modestly robed and generally seated.

But around 430 BCE, Hecate acquired her distinctive triplicate appearance. Artists began to represent the goddess as a female figure with three faces or three bodies. This iconography reflected Hecate’s role as a goddess of the crossroads, with one face (or body) corresponding to each of the crossing roads, allowing Hecate to watch over each road simultaneously.

Statues of the triple-Hecate quickly became popular. Placed on poles or columns, these images—called hecataea (singular hecataeon)—could often be found before crossroads or even in front of private homes.

Aside from her triple form, Hecate was most often identified by a polos, a kind of cylindrical crown, and by torches. She was often accompanied by dogs. It was said that the howling or barking of these dogs would announce Hecate’s presence when she wandered at night, accompanied by an entourage made up of the souls of the dead—especially the souls of girls who had died unmarried or childless.[5]

A hecataeon from ca. 50–100 CE. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands.

SailkoCC BY 3.0Hecate’s other attributes and symbols included swords, snakes, polecats, red mullets, boughs, flowers, and pomegranates. Some sources represented Hecate as the guardian of the gates of the Underworld, or even as the keeper of the keys of the Underworld.[6]

There were a handful of unique depictions of Hecate in antiquity, some of which gave the goddess frightening features. One vase, for example, shows Hecate, accompanied by the Erinyes (“Fates”), with man-eating dogs for feet.[7] By late antiquity, the Orphics sometimes imagined Hecate as a terrifying figure with three heads (of a horse, a dog, and a lion).[8]

Family

Family Tree

Mythology

The Birth of Zeus

Hecate appears in some versions of the birth of Zeus. This myth tells of how the Titan Cronus, Zeus’ father, swallowed each of his children as soon as they were born, fearing they would someday overthrow him. But when his last child, Zeus, was born, Cronus’ wife Rhea decided to save the newborn’s life at all costs. Thus, she dressed a stone in swaddling clothes for Cronus to swallow while she hid the real Zeus away.

In most traditions, it was Rhea who brought Cronus the stone for him to swallow. But in one version, depicted on the eastern frieze of the Temple of Hecate at Lagina, Rhea sends Hecate to give Cronus the stone.[22]

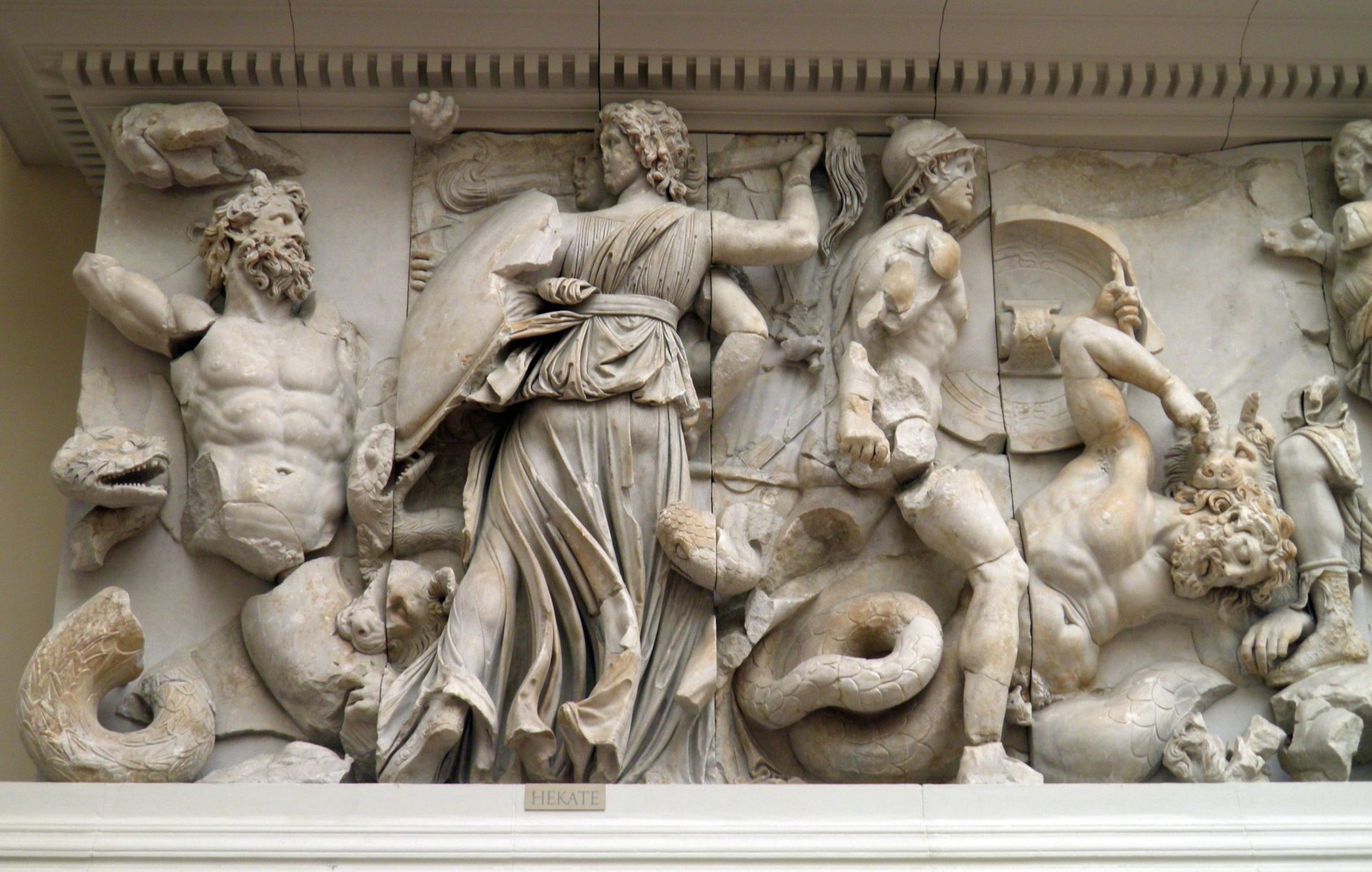

Gigantomachy

When the Olympians were attacked by the Giants, monstrous offspring of the earth goddess Gaia, Hecate sided with the Olympians. Fighting with her torches, she laid low the Giant Clytius.[23] This scene was sometimes represented in ancient art—for example, it appeared on the western frieze of Hecate’s temple in Lagina as well as on the famous Gigantomachy frieze of the Pergamon Altar.[24]

Hecate, wielding a torch, battles Clytius in this detail from the Gigantomachy frieze of the Pergamon Altar (2nd century BCE). Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany.

Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0The Abduction of Persephone

Hecate makes another appearance in the mythology of Persephone and her mother Demeter. When Persephone was abducted by her uncle Hades and spirited away to his gloomy Underworld kingdom, Hecate was the only one who heard her cries.

When Persephone’s mother, Demeter, was wandering the earth in search of her daughter, Hecate revealed what she had heard. Unfortunately, she did not know where Persephone had been taken. To find out that crucial piece of information, Hecate sent Demeter to Helios, the god of the sun, who alone could see everything that happened. Helios, in turn, revealed the truth: that Hades had taken Persephone.

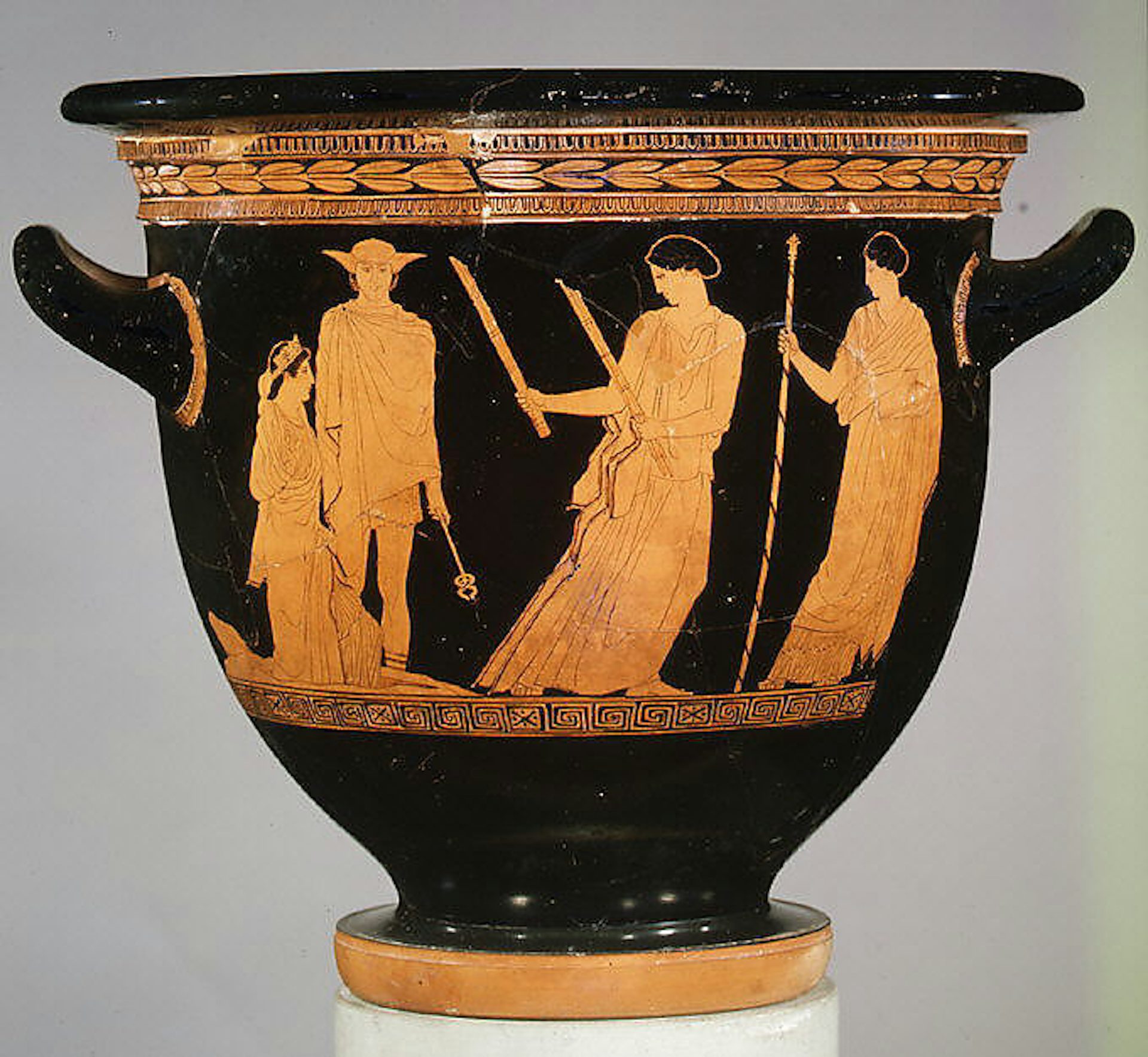

Eventually, Zeus forced Hades to restore Persephone to Demeter for at least part of the year. The girl was at last reunited with her mother and with Hecate, who became her attendant and continued to receive great honors in the cult of Demeter and Persephone (as a reward for helping with Demeter’s search).[25]

Terracotta red-figure bell-krater showing Persephone's ascension from the Underworld. Persephone (far left) is accompanied by Hermes (second from left), Hecate (center), and her mother Demeter (far right). Attributed to the Persephone Painter (ca. 440 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHecate and the Polecat

Another myth explains how Hecate became associated with the polecat (or weasel), which was one of her sacred animals. There are two versions of this myth.

One version is set at the birth of the hero Heracles. Since Heracles was the son of Zeus and his mortal lover Alcmene, Zeus’ jealous wife Hera wished to prevent his birth. She therefore sent Eileithyia (the goddess of childbirth) and the Moirae (the “Fates”) to hold Alcmene’s womb shut.

But Alcmene’s handmaid Galinthias, fearing for her mistress, tricked the goddesses: she announced that the child had already been born. Eileithyia and the Moirae, caught off guard, released their hold on Alcmene’s womb, allowing Heracles to be born. As punishment for tricking the gods, Galinthias was turned into a polecat. But Hecate took pity on her and made her into her sacred attendant.[26]

Another version tells of a witch named Gale. This witch was so sexually perverse that the gods punished her by turning her into a polecat. In this form, she was forced to serve Hecate—the god of witches.[27]

Hecate, Patron Goddess of Witches

Hecate was regularly invoked as the patron goddess of witches throughout Greek and Roman literature. Medea, the witch who helped Jason and the Argonauts in their quest for the Golden Fleece, was above all a devotee of Hecate.[28] Simaetha, whose story is told by the Hellenistic poet Theocritus, called on Hecate to help restore her lover Delphis to her.[29] Finally, Hecate features in the prayers of the Roman poet Horace’s Canidia, a cruel witch said to desecrate graves, kidnap, murder, poison, and torture.[30]

(FIGURE 5)

Worship

Temples and Sacred Spaces

Hecate had many temples in antiquity. In Athens, for example, there was a temple of Hecate Epipyrgidia (“Hecate on the Ramparts”) guarding the entrance to the Acropolis.[31]

Another important temple was located in Lagina, a town in the region of Caria on the southwest coast of Asia Minor (in modern-day Turkey). This was a monumental temple, complete with a great marble altar, decorative statues and friezes, and a courtyard. It was run by priests, priestesses, and eunuchs, each with their own distinct roles.[32]

Temple of Hecate at Lagina (outside of modern Turgut, Turkey).

RaicemCC BY-SA 4.0Other sites with temples of Hecate included Argos,[33] Samothrace,[34] and Aegina.[35]

Hecate’s sacred spaces also extended beyond temples. She was thought to control all kinds of entrances—to public spaces, private homes, roads, the Underworld, and so on. Because of this, statues or columns (called hecataea) representing her in her triple-formed guise were often found at entrances or in “liminal” spaces. Hecataea were especially common at crossroads but were sometimes also placed in front of private homes.[36]

Rituals, Festivals, and Holidays

Rituals honoring Hecate often involved food offerings. For example, she received offerings of fish, especially red mullet, which was considered taboo in other cults.[37] Cakes decorated with miniature torches were made for Hecate at the time of the full moon.[38] But, rather horrifyingly, she was also honored with the sacrifices of dogs and puppies.[39]

In Athens, which is where most of our evidence for Hecate’s worship comes from, Hecate was honored above all during new moon festivals. She would be lavished with deipna (“feasts”) made up of her favorite foods: bread, eggs, cheese, and, of course, dog meat. These would be left at crossroads all over the town and countryside.[40]

Hecate had exotic rituals in other parts of the Greek world. At her temple in Lagina, she was honored with a ritual called the kleidagōgia that involved the carrying of a sacred key (presumably representing the keys to the Underworld that Hecate was believed to possess). Hecate also had mystery cults, including at Samothrace and Aegina, where she was called upon to heal madness (among other things).[41]

Identifications and Associations

Hecate was frequently identified with other gods and mythical figures. These included Ereschigal, the Babylonian goddess of the Underworld;[42] Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon sacrificed before the Trojan War;[43] Persephone;[44] the Thessalian goddesses Enodia[45] and Brimo;[46] the Sicilian goddess Angelos;[47] Selene, goddess of the moon;[48] and, above all, Artemis[49] (there was even a shrine of Hecate at Erchia, in Attica, where sacrifices were offered to Artemis Hecate and Artemis Kourotrophos).[50]

Diana and Hecate by the circle of Rosso Fiorentino (16th century).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHecate was also associated with a handful of male gods, with whom she was sometimes worshipped. These included Apollo (as Apollo Delphinios), Asclepius, Hermes, Pan, and Zeus (as Zeus Meilichios and Zeus Panamaros).

Other Worship: Magic Papyri, Curse Tablets, and the Chaldean Oracles

Given her associations with magic, it is no surprise that Hecate was often invoked on the fringes of religious worship that dealt in magic, spells, and curses.

Hecate often appeared on “Magic Papyri,” papyrus texts produced in Egypt between 100 BCE and 400 CE that contained many obscure spells and magical formulas. Within these texts, she was usually identified with Baubo, Brimo, Persephone (or Kore), or Selene.

Hecate was also invoked on curse tablets. These tablets were engraved texts that called upon a god—usually a “chthonian” god associated with the Underworld (such as Persephone, Hermes, or Gaia)—to punish or harm an enemy, who would generally be named in the text.

Finally, the Chaldean Oracles, mystical texts produced between the third and sixth century CE, imagined Hecate in an entirely different light. Here, we find that Hecate has been transformed into the cosmic soul, an entity that can be grasped through ritual but also through contemplation.

Pop Culture

Nowadays, Hecate is remembered almost exclusively for her connections with the dark, ghostly aspects of magic and witchcraft. Though rarely encountered in modern adaptations of Greek myth, Hecate has influenced many systems of modern witchcraft and neopaganism, including Wicca. The “Triple Goddess” used by various neopagan groups is often identified with Hecate.