Cerberus

Overview

Cerberus was the offspring of Typhoeus and Echidna and the guard dog of the Underworld. A servant of Hades (the Greek god of the dead), Cerberus prevented the inhabitants of the Underworld from returning to the land of the living. He was well suited to this task: in most traditions, Cerberus was a gigantic hound with three heads and a mane of snakes. In some versions he was even more terrifying, with fifty or even one hundred heads.

As his twelfth and final labor, Heracles was sent to fetch Cerberus from the Underworld. This was the most daunting of Heracles’ deeds and was accomplished only with the aid of the gods.

Etymology

The etymology of Cerberus’ name is uncertain. Some ancient sources believed that the name “Cerberus” was derived from the Greek word kreōboros, meaning “flesh-devouring.”[1]

Modern scholars mostly dismiss this etymology, but they agree on little else. Some have attempted to trace the name to an Indo-European origin through the Sanskrit sarvarā (“spotted”), the epithet of one of the dogs of Yama (the god of death).[2] Bruce Lincoln, a professor of religion at the University of Chicago, has suggested a connection with Garmr, one of Hel’s guard dogs in Norse mythology.[3] According to Lincoln, both names may have been derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *ger-, meaning “to growl.”

Such Indo-European etymologies have been met with skepticism, however.[4] Whatever the origins of Cerberus’ name, it is most likely pre-Greek.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Cerberus Κέρβερος Phonetic

IPA

[SUR-ber-uhs] /ˈsɜːrbərəs/

Alternate Names

In Homer, Cerberus was called simply “the hound” (kyōn).[5] Other sources called him “the hound of Hades.”

Titles and Epithets

The epithet trikranos, “three-headed,” was sometimes used for Cerberus.

Attributes

Appearance and Abilities

Ancient sources offered conflicting accounts of Cerberus’ appearance. According to Hesiod, the earliest author to give a description of him (in the eighth or seventh century BCE), Cerberus had fifty heads.[6] Pindar, writing in the fifth century BCE, gave Cerberus one hundred heads.[7] Almost all later sources, however, limited him to just three heads, with snakes along his mane and back, and a snake tail.[8] One notable exception is the Roman poet Horace (65–8 BCE), who gave Cerberus a single head with three tongues, ringed by one hundred snakes.[9]

John Tzetzes, an eleventh-century CE Byzantine poet and scholar, sought to reconcile these conflicting versions by giving Cerberus fifty heads—three of them dog heads, and the rest heads of various other beasts.[10] Cerberus was usually represented with only one body, but according to the Athenian tragedian Euripides[11] and the Roman poet Virgil,[12] he had multiple bodies in addition to multiple heads.

Hades, the god of the dead, posted Cerberus at the gates of the Underworld. Rather than preventing people from coming in, like most guard dogs, Cerberus’ job was to ensure that nobody left. According to Hesiod, Cerberus had “a cruel trick” to help him with this task:

On those who go in he fawns with his tail and both his ears, but suffers them not to go out back again, but keeps watch and devours whomsoever he catches going out of the gates of strong Hades and awful Persephone.[13]

In later sources, Cerberus’ abilities expanded beyond a mere taste for raw flesh: it was said that his eyes flashed fire,[14] his jaws dripped venom,[15] and his hearing was unparalleled.[16]

Iconography

Cerberus was a popular subject for ancient artists from an early period. He is known to have appeared on the Throne of Amyclae, a monument to the god Apollo constructed in the sixth century BCE.[17]

Ancient artists depicted Cerberus with three, two, or even just one head (but never with more than three). He was also often shown with snakes growing out of his body or with a snake tail.[18]

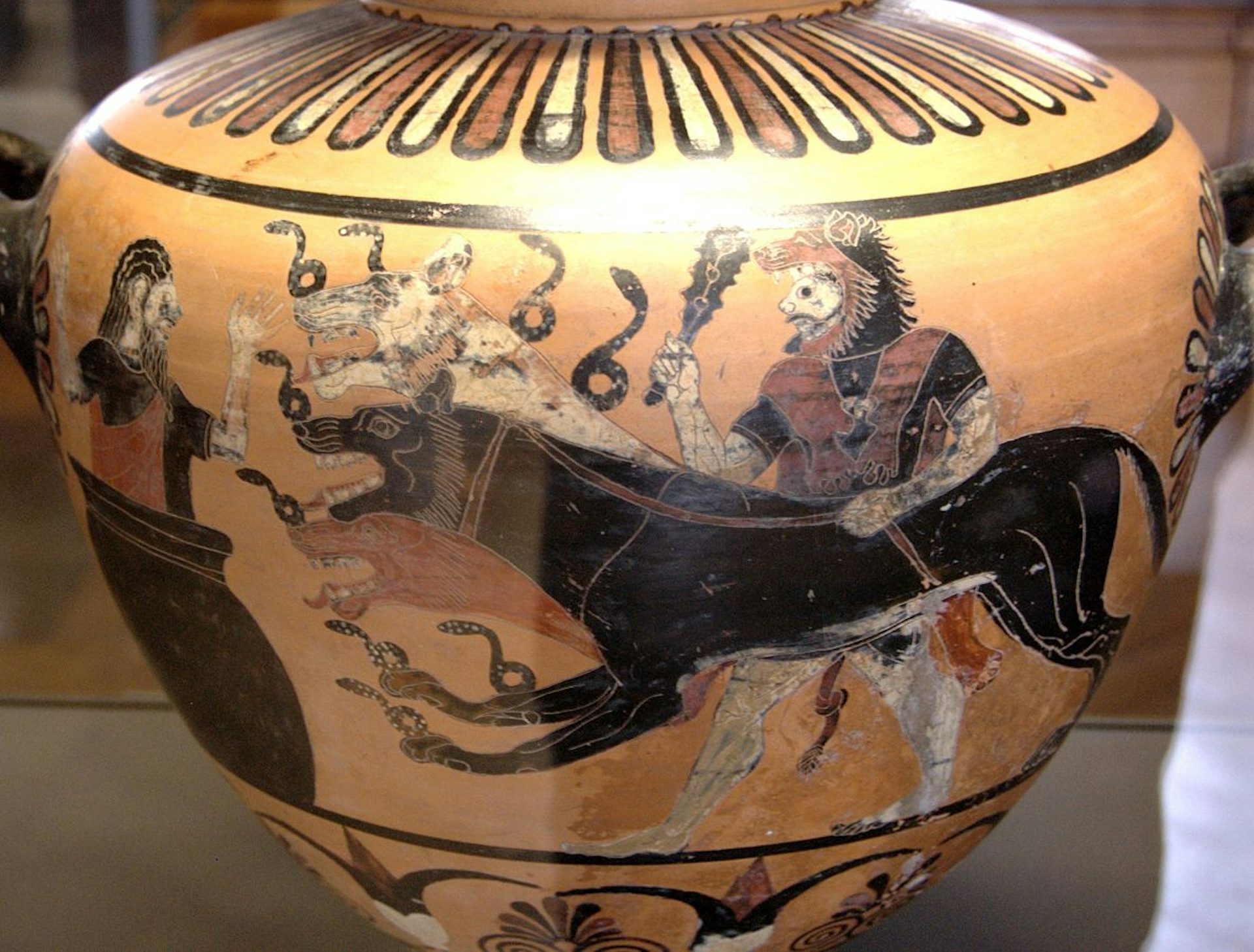

Hydria showing Heracles bringing Cerberus to Eurystheus by the Eagle Painter (c. 525 BC).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFamily

Family Tree

Mythology

Heracles’ Twelfth Labor

Cerberus is best known through his connection with the myth of Heracles. As his twelfth and final labor for Eurystheus, the king of Mycenae, Heracles was sent to fetch Cerberus from the Underworld. Like Heracles’ other labors, this task was expected to be impossible, but Heracles managed to accomplish it anyway.

Preparation and Descent to the Underworld

In his quest to capture Cerberus, Heracles received considerable assistance. According to many traditions, he prepared for his descent to the Underworld by becoming an initiate of the Eleusinian Mysteries,[20] a cult of Demeter and Persephone that promised worshippers a privileged afterlife. Heracles’ initiation into these mysteries helped him pass through the Underworld unharmed.

In many accounts, Heracles received further help from either Hermes, the messenger of the gods (but also the guide to the Underworld),[21] Athena,[22] or both Hermes and Athena.[23] Hermes and Athena were also depicted in many artistic representations of Heracles’ Twelfth Labor.

When he entered the Underworld, Heracles fought one of Hades’ henchmen (named either Menoetes[24] or Menoetius[25]) and freed Ascalaphus (who had once angered Demeter).[26] He was also said to have encountered Theseus and Pirithous, two companions who had been taken prisoner by Hades while trying to carry off his wife Persephone. In most traditions, Heracles was able to rescue Theseus but not Pirithous.[27]

The Capture of Cerberus

There were different accounts of how Heracles ultimately captured Cerberus.

In the most familiar version of the myth, Heracles presented himself before Hades and asked to “borrow” Cerberus. Hades agreed, but only if Heracles “mastered [Cerberus] without the use of the weapons which he carried.”[28] The hero then wrestled the hound with the invulnerable skin of the Nemean Lion as protection, finally managing to subdue and restrain him.

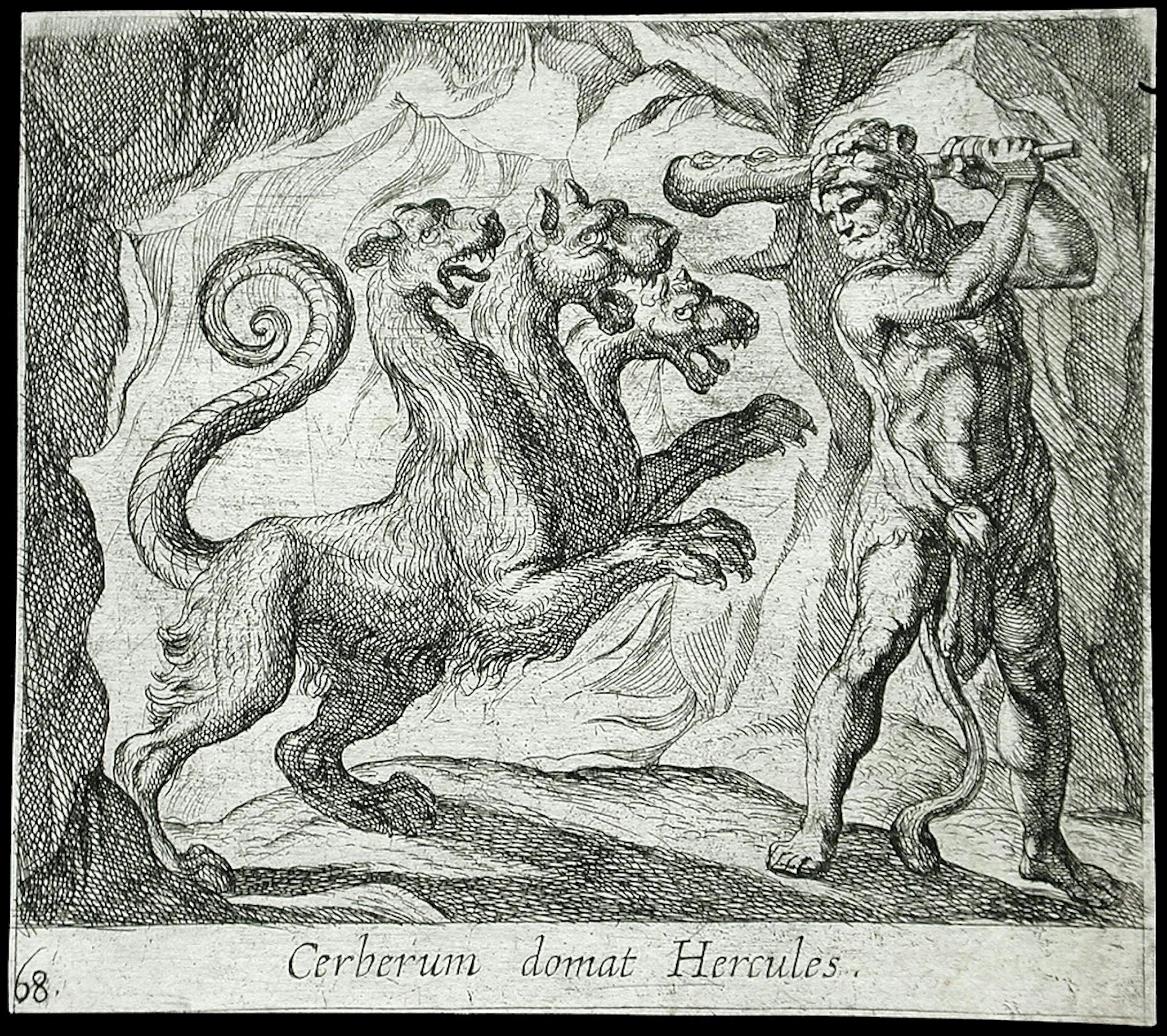

In artistic representations, on the other hand, Heracles was often shown fighting Cerberus with a club or even a stone. In the Roman tragedy Hercules Mad by Seneca (first century BCE or first century CE), it is reported that the hero used his club to subdue Cerberus.[29]

Cerberum domat Hercules ("Hercules Tames Cerberus"), etching by Antonio Tempesta (1606).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThere also seems to have been an early version of the myth in which Heracles needed to fight Hades for Cerberus.[30] In one story, Hades refused to let Heracles take Cerberus even after he had beaten him without weapons; justifiably angry, Heracles shot Hades with an arrow.[31] In other versions, it was Persephone, Hades’ queen, who delivered Cerberus to him.[32]

After capturing Cerberus, Heracles bound him in chains and dragged him out of the Underworld.

Leaving the Underworld

Now that Heracles had captured Cerberus, he needed to bring him to King Eurystheus in Mycenae. This was no easy task: Cerberus did not leave the Underworld willingly. The ferocious guard dog raged as Heracles dragged him, for the first time, into the light of day. According to some accounts, Cerberus vomited or foamed a toxic bile as he was brought into the world of the living, and from this bile grew the poisonous aconite plant.[33]

Hercules and Cerberus by Peter Paul Rubens (1636).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainBefore bringing Cerberus to Eurystheus, Heracles paraded the guard dog of death throughout Greece. After he had displayed the creature to Eurystheus, Cerberus was returned to the Underworld, where he reprised his old post as the infernal guard dog.

Orpheus

Heracles was one of only a few mortals who entered the Underworld alive and managed to come back; another was the musician Orpheus. After losing his wife Eurydice on their wedding day, Orpheus vowed to retrieve her from the clutches of death.

In contrast to Heracles, Orpheus invaded the Underworld not by brawn but by his musical talent; he played and sang so beautifully that he moved the infernal gods to grant him safe passage through the land of the dead. The Roman poet Virgil wrote that, upon hearing Orpheus’ music, “Cerberus stood agape and his triple jaws forgot to bark.”[34] Thus, Cerberus was once again subdued by an extraordinary mortal.

Pop Culture

In modern pop culture, Cerberus most often appears in adaptations of the Heracles myth, such as the 1997 Disney film Hercules and the 1990s TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys. In the 2014 film Hercules, Cerberus is reimagined as a more realistic enemy: three wolves that the hero must fight.

Outside of film, Cerberus is a “summon” in the video game Final Fantasy VIII. In J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997), the three-headed dog Fluffy was inspired by Cerberus.