Asclepius

The Finding of Aesculapius by Giovanni Tognolli (between 1822 and 1839)

Walker Art Gallery, LondonPublic DomainOverview

Asclepius, the son of Apollo and a mortal princess, was one of only a handful of figures in Greek mythology who was worshipped as a hero as well as a god. He grew up to be a renowned physician, so skilled that he even had a cure for death. But his talents (especially his ability to raise the dead) threatened the order of the cosmos, leading Zeus to kill him with a lightning bolt.

In time, the Greeks came to regard Asclepius as one of their most important gods—the god of medicine and healing. He received worship in temples and cult centers throughout the ancient Mediterranean. A benevolent god, he was thought to appear to the sick in dreams with instructions on how they could cure themselves of their ailments.

How was Asclepius born?

Like many other important mythological figures, Asclepius was not born under the best of conditions. He was conceived from the union of the god Apollo and the Thessalian princess Coronis or Arsinoe (there were different versions). But when Coronis/Arsinoe was unfaithful to Apollo, the god had her killed.

As his former lover lay on her funeral pyre, Apollo cut her unborn child from her womb. Apollo gave the child—Asclepius—to the wise centaur Chiron, who raised him and taught him important skills.

The Finding of Aesculapius by Giovanni Tognolli (between 1822 and 1839)

Walker Art Gallery, LondonPublic DomainWhat were Asclepius’ attributes?

Asclepius was the prototypal physician of Greek mythology. He was usually represented with a beard and long, curly hair, wearing a coak that left his chest exposed.

Asclepius’ most distinctive attribute was his staff or rod. A snake—which the Greeks associated with healing and medicine—was often shown coiled around this rod. Dogs were also dear to Asclepius.

Statue of Asclepius, Roman copy (ca. 160 CE) after a 4th-century BCE Greek original, from the Temple of Asclepius at Epidaurus

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / MarsyasCC BY-SA 3.0Was Asclepius a god?

Asclepius was one of the few figures of Greek mythology who was worshipped as both a hero and a god. Though mortal by birth, he became the most important healing god of the Greek pantheon. Asclepius had sanctuaries throughout the Greek world, including a particularly famous one at Epidaurus.

The Offering to Asclepius by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1803)

Museum of Fine Arts, ArrasPublic DomainAsclepius Cures Death

In myth, Asclepius’ healing skills eventually grew so formidable that he was able to cure death. But bringing a dead man back to life was seen as a dangerous infringement on the powers of the gods. Thus, to preserve the cosmic order (and his own authority), Zeus killed Asclepius by striking him down with a thunderbolt.

Asclepius’ father Apollo was devastated at the death of his son. In a fit of heartbroken fury, he killed the Cyclopes, the one-eyed creatures who had fashioned Zeus’ thunderbolts for him. Eventually, however, Asclepius ascended to the ranks of the immortals, becoming the Greek god of healing.

Marble relief showing Asclepius (left) and his daughter Hygieia (right) (1st century CE)

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden / NearEMPTinessCC BY-SA 4.0Etymology

The etymology of the name “Asclepius” (Greek Ἀσκληπιός, translit. Asklēpios) remains unknown. Some have connected it to the Hittite roots aššula(a)- (“well-being”) and pai/pi- (“to give”). Others have suggested a connection with the Greek words aiglē and aglaos, meaning “glorious” (often found in epithets of Asclepius’ father, Apollo).

Finally, some have pointed out that Asclepius’ name contains elements typical of Pre-Greek names (a/ai followed by -glap- or -sklap-/schklap/b-) and may thus have been Pre-Greek in origin (Robert Beekes reconstructs the original form of the name as *(a)-sʸklap-).[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Asclepius Ἀσκληπιός (translit. Asklēpios) Phonetic

IPA

[uh-SKLEE-pee-uhs] /əˈskli pi əs/

Alternate Names

In ancient Greece, Asclepius’ name existed in a number of different variants. The most common form was Ἀσκληπιός (Asklēpios), but other attested forms include the Doric and Aeolian Ἀσκλαπιός (Asklapios) and the Boeotian Ἀσχλαπιός or Αἰσχλαβιός (Aschlapios or Aischlabios).

In one little-known tradition, recorded by the Byzantine scholar and poet John Tzetzes, Asclepius’ name was originally Hepius and was only changed to Asclepius after he cured the Epidaurian king Ascles.[2]

The Romans, who adopted the worship of Asclepius relatively early, Latinized his name as Aesculapius (which remains a common alternate spelling).

Titles and Epithets

Asclepius had a large number of epithets in the ancient world, an indication of his significance as a hero and god. Some of his most important and familiar epithets include iatros (“healer”), amymōn (“peerless”), and sōtēr (“savior”). Asclepius was also sometimes addressed as paian, a distinctive title usually used to call on a god as healer (and most often associated with Asclepius’ father, Apollo).

Attributes and Iconography

As both hero and god, Asclepius represented the supreme physician. He was worshipped by the Greeks as the god of medicine and healing.

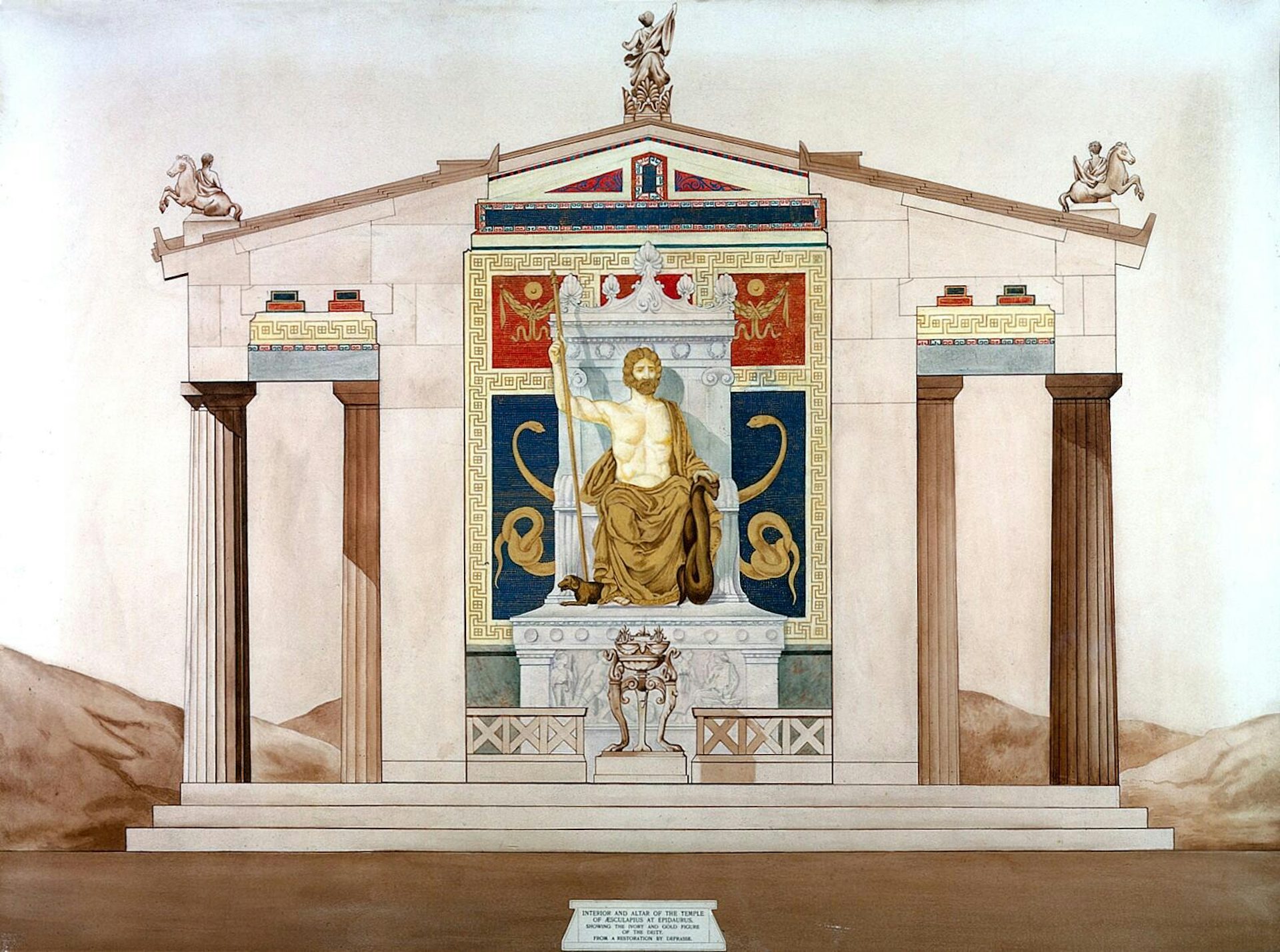

In his iconography, Asclepius was usually depicted as a mature man with a beard and long, curly hair, wearing a cloak that wrapped over one shoulder and left his broad chest exposed. He was typically shown standing, but in one of his most famous ancient representations—the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of him from Epidaurus—he was seated on a throne.[3]

Reconstruction showing what the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Asclepius at Epidaurus may have looked like. Drawing by Alphonse Defrasse, from Henri Lechat's Epidaure, restauration et description des principaux monuments du sanctuaire d'Asclépios (1895).

Wellcome CollectionPublic DomainAsclepius’ most important symbols or attributes were the staff and the snake. The snake was often coiled around the staff, forming the famous “Rod of Asclepius.” Occasionally, he was also represented with a dog.[4]

The Roman author Hyginus gives a mythical account of how Asclepius came to be associated with the snake:

When [Asclepius] was commanded to restore Glaucus, and was confined in a secret prison, while meditating what he should do, staff in hand, a snake is said to have crept on to his staff. Distracted in mind, [Asclepius] killed it, striking it again and again with his staff as it tried to flee. Later, it is said, another snake came there, bringing an herb in its mouth, and placed it on its head. When it had done this, both fled from the place. Where upon [Asclepius], using the same herb, brought Glaucus, too, back to life.[5]

In reality, it is more likely that the snake became Asclepius’ symbol because of the creature’s supposed healing properties. Snakes were often found in temples of Asclepius,[6] and it was even said that Asclepius sometimes took the form of a serpent in his “epiphanies” (his appearances to mortals).[7]

Family

Asclepius’ father was Apollo, the Olympian god associated with healing, prophecy, and the arts.[8] His mother, however, was less certain. According to the best-known version, Asclepius’ mother was a mortal woman from Thessaly named Coronis.[9] But in other versions, she was a Messenian woman named Arsinoe.[10] There was also supposedly a Phoenician version in which Asclepius was fathered by Apollo without a mother.[11]

Marble relief of Asclepius and his daughter Hygieia, the personification of health. From Thermae (late 5th century BCE). Istanbul Archaeological Museums, Istanbul, Turkey.

PriorymanCC BY-SA 3.0Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

The mythology of Asclepius’ origins is rather tangled. From an early date, there were two different genealogies in circulation: in one, Asclepius was the son of Apollo and Coronis, daughter of the Thessalian Phlegyas; in another, he was the son of Apollo and Arsinoe, daughter of the Messenian Leucippus. Thus, both Thessaly (in northern Greece) and Messenia (in southern Greece) laid claim to Asclepius, though the Thessalian version was probably more widely accepted.

Regardless of the genealogy, the myth of Asclepius’ birth seems to have generally been the same. Coronis (or Arsinoe) was loved by Apollo and became pregnant with Asclepius. But Coronis/Arsinoe ultimately married a mortal named Ischys. When Apollo heard about the marriage from a raven, he punished the bird for his ill tidings by turning him black. Then he (or his sister Artemis) killed Coronis/Arsinoe.

When Coronis/Arsinoe lay upon the funeral pyre, Apollo (or his brother Hermes) saved his son by cutting open the dead girl’s womb and snatching him away. Asclepius was then raised by the wise centaur Chiron.[16]

Woodcut depicting the birth of Asclepius, from Alessandro Beneditti's De Re Medica (1549).

Research GatePublic DomainIn a later version of the myth, Asclepius was again the son of Apollo and Coronis. This time, however, Coronis gave birth to the child while traveling with her father and subsequently abandoned him in the city of Epidaurus (in central Greece). There, the baby was suckled by a goat and guarded by a dog before being found and raised by a shepherd named Arethanas.[17]

Asclepius and the Art of Medicine

Asclepius grew up to become a remarkably talented physician. According to Pindar,

those who came to him afflicted with congenital sores, or with their limbs wounded by gray bronze or by a far-hurled stone, or with their bodies wasting away from summer's fire or winter's cold, he released and delivered all of them from their different pains, tending some of them with gentle incantations, others with soothing potions, or by wrapping remedies all around their limbs, and others he set right with surgery.[18]

Asclepius eventually became so skilled in the art of medicine that he could even cure death. According to one tradition, he was ordered to restore the life of Glaucus, the son of the powerful King Minos, and was locked up in a dungeon until he complied.

While in the dungeon, Asclepius saw a snake and promptly killed it. Later, he spied another snake entering the dungeon carrying an herb. When this snake put the herb in the mouth of the dead snake, the deceased creature came back to life. Upon seeing this, Asclepius used the herb to bring Glaucus back from the dead.[19]

According to a different tradition, it was the goddess Athena who gave Asclepius what he needed to raise the dead: the blood of the Gorgon Medusa. Asclepius realized that while the blood from the left side of the monster was poisonous, the blood from the right side was a powerful panacea that could cure death.[20]

In some traditions, Asclepius was one of the Argonauts[21] and participated in the Calydonian Boar Hunt.[22]

Death and Deification

Asclepius’ astonishing abilities eventually provoked the anger of the gods. By raising the dead (including Glaucus, Theseus’ son Hippolytus, and the Spartan king Tyndareus, according to various sources), Asclepius became guilty of violating the natural order of the cosmos. Fearing that there would soon be nobody left in the Underworld, Zeus killed Asclepius with a lightning bolt.[23]

Illustration of Asclepius resurrecting the dead Hippolytus by Antonio Tempesta (1606). From edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEnraged, Asclepius’ father Apollo lashed out. He did not dare to attack the all-powerful Zeus directly, so he took out his anger on the Cyclopes (or, in some versions, their sons), who were responsible for fashioning the lightning bolt Zeus had used to strike down Asclepius.[24] Zeus, in turn, punished Apollo by forcing him to become the slave of the mortal Admetus.

Asclepius, however, did not remain dead for long. Indeed, the Greeks worshipped him as a god (not just a hero), suggesting that at some point he was resurrected, made immortal, and deified.[25]

Worship

Temples

There were hundreds of temples of Asclepius (called Asclepiaea, or Asclepiaeon in the singular) in the ancient world. One of the oldest ones was in Tricca, regarded locally as the place where the god had been born.[26] There was another impressive (but likely more recent) temple of Asclepius at Messenia, which a rival local tradition also claimed as the site of the god’s birth.[27]

The cult of Asclepius began rapidly expanding during the fifth century BCE. It was during this time that the two most important ancient cults of Asclepius were established on the Aegean island of Cos and in the central Greek city of Epidaurus.

Both Cos and Epidaurus boasted a great Asclepiaeon. Cos was also home to a school of physicians known as the Asclepiadae.[28] Hippocrates, the most famous physician of ancient Greece, was a member.

Ruins of the Temple of Asclepius in Epidaurus.

ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0The Asclepiaeon of Epidaurus became particularly renowned. It was surrounded by a sacred complex and a grove in which it was forbidden for anyone to die or be born.[29]

The cult of Asclepius continued to spread throughout Greece, with special help from Epidaurus.[30] Asclepius thus came to Sicyon,[31] Aegina,[32] Tegea,[33] and Athens, where he was worshipped first at the harbor of the Piraeus and then, by the end of the fifth century BCE, on the slopes of the Acropolis.[34]

The cult also spread to other, more distant sites, including Pergamum and Smyrna in modern-day Turkey and even Italy. The Asclepiaeon of Rome, established in 293 BCE, became quite important. Suffering from a severe plague, the Romans had been instructed by an oracle to import the cult of Asclepius from Epidaurus. A great temple was built on Tiber Island after the sacred snake of Asclepius, brought by boat from Epidaurus, chose it as its new home.[35]

Asclepiaea temples tended to share certain features. For example, they were usually located outside of the main town, often in a valley or by the seashore.[36] Like the temples of other gods, Asclepiaea also included a statue or “cult image” of Asclepius, situated in a prominent place; particularly famous was the giant chryselephantine cult image in the Asclepiaeon of Epidaurus.[37] Most Asclepiaea also had a sacred snake who lived in the sanctuary, and some, like the one at Epidaurus, had a sacred dog.

The central feature of the Asclepiaea was an incubation room (called an enkoimētērion in Greek). Sick worshippers could sleep in this special room in the hope that Asclepius would appear to them and cure them, or tell them in a dream how they could cure themselves. Those who had been cured in this way would dedicate a tablet or stele in which they described how the god had helped them and gave thanks. Many such tablets still survive, detailing some remarkable illnesses and cures.[38]

Finally, Asclepius was frequently worshipped together with the other members of his healing family: his father Apollo, his sons Machaon and Podalirius, and his daughters (especially Hygieia).

Festivals and Holidays

The festival of Asclepius, called the Asclepiaea, was celebrated wherever there was an Asclepiaeon (a temple of Asclepius). The Asclepiaea of Epidaurus, held every fifth year, were particularly important. These included athletic as well as musical competitions.[39]

Athens, which had another important sanctuary of Asclepius, celebrated both an Asclepiaea (twice per year) and an Epidauria (to commemorate the day when Asclepius was brought to Athens from Epidaurus).[40]

On feast days and in his various temples, Asclepius received different types of sacrifices. These included standard burnt sacrifices,[41] but also hair sacrifices to him or his daughter Hygieia.[42]

Pop Culture

Asclepius is largely absent from modern pop culture; today, Olympian gods such as Zeus, Poseidon, and Athena or warrior-heroes such as Heracles and Achilles are much more familiar to the general public. But Asclepius is still occasionally mentioned in some contemporary adaptations of Greek mythology, such as the 1990s TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians franchise.

The “Rod of Asclepius” (sometimes called the “Staff of Asclepius”)—the symbol of Asclepius’ snake-entwined staff—has become a popular logo for many medical services and organizations, including the World Health Organization. Unfortunately, the Rod of Asclepius is sometimes confused with the caduceus, a wand entwined with two snakes (not just one) and used by the god Hermes to convey the souls of the dead to the Underworld.

Flag of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain