Argus Panoptes

Mercury, Argus and Io by Abraham Bloemaert (ca. 1592).

Centraal MuseumPublic DomainOverview

“All-seeing” Argus was an enormous monster covered in countless eyes. Unsleeping, ever-vigilant, and loyal, he was a servant of the goddess Hera. In her jealousy, Hera had tasked Argus with guarding Io, a lover of her husband Zeus. But Zeus sent Hermes to liberate Io, and the messenger god slew Argus in the process.

In some traditions, Hermes used brute force against Argus. But in the more familiar account, he outsmarted Argus, lulling him to sleep with his music and then cutting off his head once all of his eyes were closed. Hera, grieved at the death of her loyal servant, either transformed Argus into a peacock or placed his many eyes on the peacock’s tail feathers.

Etymology

The name “Argus” (Greek Ἄργος, translit. Árgos) seems to be derived from the word ἀργός (argós), which means both “shining, brilliant” and “quick, agile.” This word, in turn, comes from the Indo-European *h₂rǵ-, meaning “white.”[1] Several mythological figures were given the name Argus—many of them, unsurprisingly, associated with the city of Argos in the Peloponnese.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Argus Ἄργος (Árgos) Phonetic

IPA

[AHR-guhs] /ˈɑr gəs/

Titles and Epithets

Argus’ most famous epithet was πανόπτης (panóptēs), “all-seeing.” This epithet was frequently used as a sort of surname, so that we often hear Argus referred to as “Argus Panoptes.”

Attributes

General

Argus, a gigantic man usually connected with the city of Argos, was best known for his numerous eyes. Though ancient sources all agreed that he possessed an unusual number of eyes, there was some debate over the exact number. According to Pherecydes, Argus had three eyes, with his extra eye placed on the back of his head by Hera.[2] According to the Aegimus, an obscure lost poem attributed to Hesiod, he had four eyes, two of them on the back of his head.[3] Many later authors did not specify the exact number of eyes, instead saying that he had many eyes all over his body,[4] while the Roman poet Ovid gave Argus one hundred eyes.[5]

Argus used his abundant eyes to great effect. He did not need to sleep, though some sources noted that if he did become tired, he could close some of his eyes while leaving the rest open and awake.[6]

Argus was also very large and strong. He wore a bull’s hide, taken from a bull that he had killed in Arcadia.[7] One (very late) author included Argus “Panoptes” in a list of the Giants—monstrous children of the primordial earth goddess Gaia who had tried to overthrow the Olympian gods[8]—but this was not the standard tradition.

Iconography

In ancient art, Argus was most often depicted guarding Io or battling Hermes. From the fifth century BCE on, artists represented him with eyes all over his body, giving him a very distinctive and easily identifiable appearance. But some representations were more unusual, with one black-figure amphora from the late sixth century BCE showing Argus as a Janus-like figure, with faces on the front and back of his head.[9]

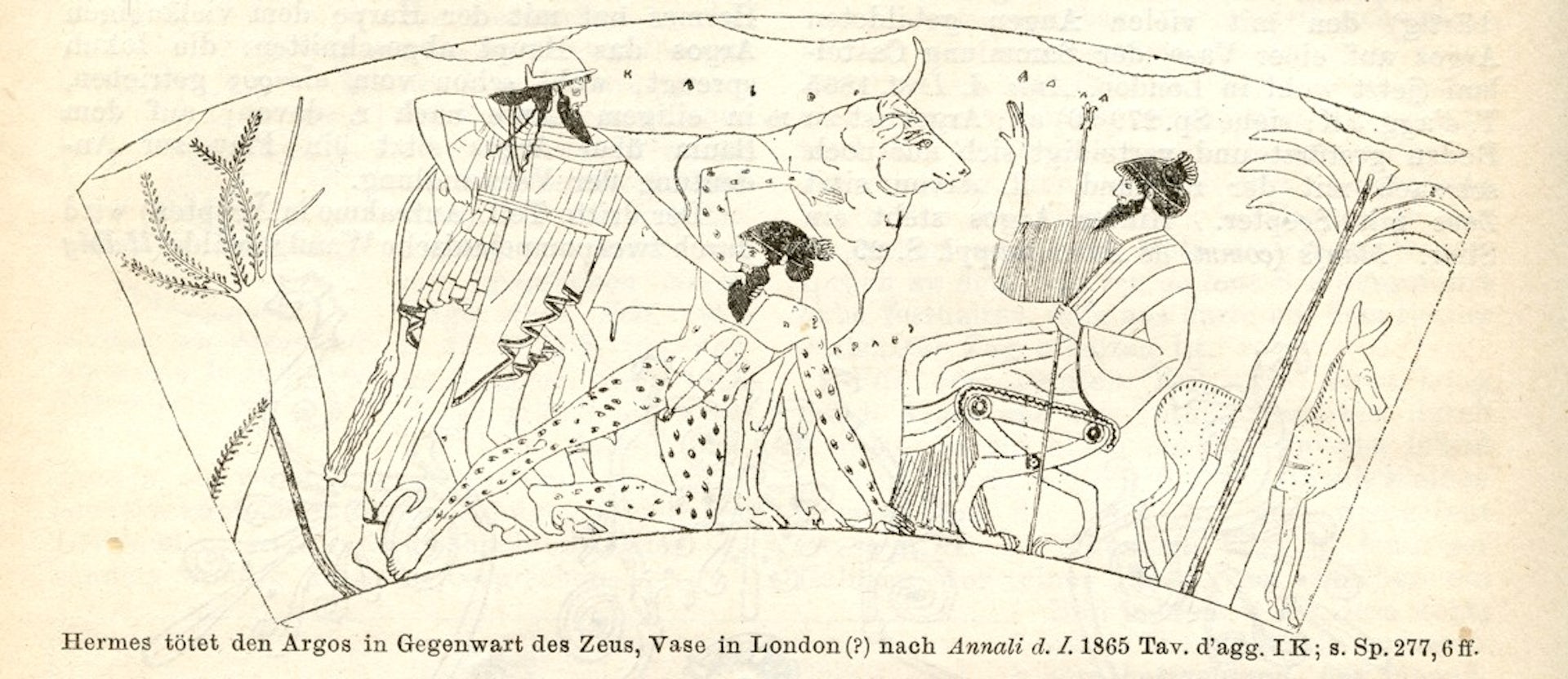

Illustration of an Attic red-figure stamnos showing Argus killing Argus, represented here with eyes all over his body (fifth century BCE). From Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher, 1890.

Wilhelm Heinrich RoscherPublic DomainFamily

Family Tree

Parents

Fathers

Mothers

- Argus (son of Zeus)

- Arestor

- Inachus

- Ecbasus

Mythology

The Deeds of Argus

Though Argus was best known for his role in the myth of Io, he carried out other impressive feats as well. Argus killed the monster Echidna, who had been attacking and robbing travelers, by sneaking up on her as she slept. He also killed a bull that was ravaging Arcadia and a satyr who had robbed the people of Arcadia of their cattle. Finally, back in Argos, he avenged the late Argive king Apis by putting the man’s murderers to death.[16]

The Guardian of Io

Hera enlisted the services of Argus when she wished to punish her enemy Io. Io was an Argive princess who had once been a priestess of Hera. But Zeus, Hera’s husband, fell in love with Io, and the two became lovers. When Hera discovered the affair, she transformed Io into a cow, but this did not have the effect Hera had hoped for: instead of ending the affair, Zeus simply transformed himself into a bull and continued sleeping with Io. In a rage, Hera whisked Io away and appointed Argus (who in some traditions was Io’s relative)[17] to stand guard over her.

Argus was a natural choice for this task: he had many eyes (as many as a hundred in some accounts) and did not need to sleep. In one tradition, however, it was Hera who equipped Argus to be an effective guardian by giving him a third eye and removing his need to sleep.[18] In an effort to put an end to Zeus’ affair, the loyal Argus tied Io to an olive tree in the sacred grove where Hera had hidden her, somewhere between Argos and Mycenae.[19]

Wall painting showing Argus guarding Io, represented here with cow horns rather than as a cow. From the House of Meleager (first century CE).

ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0Zeus soon learned what had happened to his bovine lover and sent Hermes to set Io free. In the most familiar tradition, Hermes used trickery to kill the unsleeping Argus; he lulled him to sleep with the sweet music of his flute, and then—when every last one of Argus’ eyes was shut in peaceful slumber—he cut off his head:

While Hermes pip’d, and sung, and told his tale,

The keeper’s winking eyes began to fail,

And drowsie slumber on the lids to creep;

’Till all the watchman was at length asleep.

Then soon the God his voice, and song supprest;

And with his pow’rful rod confirm’d his rest:

Without delay his crooked faulchion drew,

And at one fatal stroke the keeper slew.

Down from the rock fell the dissever’d head,

Opening its eyes in death; and falling, bled;

And mark’d the passage with a crimson trail:

Thus Argus lies in pieces, cold, and pale;

And all his hundred eyes, with all their light,

Are clos’d at once, in one perpetual night.[20]

In a different version, however, a certain Hierax (“hawk”) blabbed and revealed Hermes’ plot so that stealth was no longer an option. As a result, Hermes killed Argus by simply throwing a large stone at him.[21]

Hermes’ slaying of Argus gave rise to one of the god’s most important epithets: ἀργειφόντης (argeiphóntēs), or “slayer of Argus.”[22] This myth was also used to explain Hermes’ connection with stone heaps: when Hermes was put on trial for the murder of Argus, the gods used pebbles to cast their votes for his acquittal.[23]

Hera, meanwhile, grieved for her loyal servant Argus. She either transformed the dead Argus into a peacock or placed his many eyes on the peacock’s tail feathers.[24] She then continued to hound Io, sending a gadfly to torment her; in at least one account, the maddened Io believed this gadfly to be the phantom of Argus.[25]

Pop Culture

Argus is still sometimes remembered in modern pop culture. In Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians franchise, he is reimagined as a laconic security guard in the service of the Olympian gods (still covered in eyes, of course). Several animals with eye-spot patterns have also been named after Argus, including the Argus gecko, the Argus monitor, and the species of pheasant known as the great argus.