Works and Days

Pandora by Walter Crane (1885)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOverview

The Works and Days is an early Greek epic poem, composed around 700 BCE by the poet Hesiod (who also authored the Theogony). It is an important example of didactic poetry and a key source for many Greek myths.

The content of the Works and Days is extremely varied. Addressed to Hesiod’s brother Perses, the text combines farming instructions and a farmer’s calendar (the “Works” and “Days” parts of the poem, respectively) with mythological stories, fables, religious and ethical advice, and proverbial maxims. The result is a mine of information on early Greek literature, mythology, religion, and social life.

Title

The title Works and Days is a translation of the Greek Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι (translit. Erga kai Hēmerai). Some scholars still refer to the poem by its Latin name, Opera et Dies.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Works and Days Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι (translit. Erga kai Hēmerai) Phonetic

IPA

[wurkz uhnd deyz] /wɜrkz ænd deɪz/

Author

Hesiod, the author of the Works and Days, is one of the earliest known Greek poets. He belonged to the Archaic period of ancient Greek history (ca. 900–490 BCE), which saw important developments in technology, trade, the arts, and social life.

Hesiod and the Muses by Gustave Moreau (1860)

Musée National Gustave Moreau, ParisPublic DomainHesiod tells us a bit about his life in his own poetry—that he was the son of a poor tradesman and grew up in Ascra, a “miserable hamlet”[1] in Boeotia (in central Greece); that he was a shepherd until the Muses appeared to him one day and taught him to compose poetry;[2] that he once won a musical contest in Chalcis;[3] and that he had a brother named Perses who cheated him of his inheritance.[4] This sparse autobiography was later embellished, sometimes with rather unbelievable details.

Though debate continues over Hesiod’s life—who he was, when he lived, and whether a single “Hesiod” even existed—most scholars today agree that Hesiod lived around the end of the eighth century BCE and that he authored two works: the Theogony (in which Hesiod actually refers to himself by name) and the Works and Days. The many other poems attributed to Hesiod in antiquity—including the Shield of Heracles, the Catalogue of Women, and the Astronomy, among others—were most likely composed by someone else at a later period.

Mythological Context

The Works and Days is not a narrative poem like Hesiod’s other epic, the Theogony. Instead, it is a didactic poem that sets out to teach valuable lessons to the reader or addressee (in this case, the poem is addressed to the author’s wayward brother, Perses). Often, myths are used to demonstrate these lessons.

Some of the myths that appear in the Works and Days are familiar from other sources. The stories of Prometheus and Pandora, for instance, are also recounted in the Theogony. Other myths are more unique and may have been invented, in whole or in part, specifically for the Works and Days.[5]

The way Hesiod uses myth can be challenging. He begins the Works and Days with the curious remark that “after all, there was not one kind of Strife alone, but all over the earth there are two.”[6] This is evidently a correction of an earlier claim in the Theogony, where he had outlined the genealogy of just one “Strife” (the goddess Eris).[7] Hesiod, then, seems to treat mythology as something that is adaptable, malleable, and evolving.

Sometimes Hesiod’s contradictory use of myth is less self-conscious. For instance, both the myth of Pandora[8] and the Myth of the Races[9]—which are told back to back—are meant to explain the origins of human suffering. The use of two seemingly unrelated myths to explain the same phenomenon may seem odd or unnecessary to contemporary readers, but it is merely an example of “overdetermination”—that is, attributing more than one cause to the same event. This is a common feature of mythical narratives across the ancient world.

In his overarching message and worldview, however, Hesiod is fairly consistent. The Works and Days, like the Theogony, is markedly devoted to the power and justice of Zeus. Indeed, the poem opens with an eloquent hymn to Zeus:

Muses of Pieria who give glory through song, come hither, tell of Zeus your father and chant his praise. Through him mortal men are famed or unfamed, sung or unsung alike, as great Zeus wills. For easily he makes strong, and easily he brings the strong man low; easily he humbles the proud and raises the obscure, and easily he straightens the crooked and blasts the proud,—Zeus who thunders aloft and has his dwelling most high. Attend thou with eye and ear, and make judgements straight with righteousness.[10]

Throughout the poem, it is Zeus who represents the order of the cosmos, ensuring that justice is dispensed. Justice (Dike) is at one point represented as the daughter of Zeus; she reports the good and evil deeds of mortals to her father.[11] Humans, who are utterly powerless before Zeus and the other gods, must obey Zeus’ will or suffer the consequences.

Prometheus Bound by Peter Paul Rubens (1618)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia / Google Arts & CulturePublic DomainThe Works and Days was undoubtedly shaped by the historical climate in which it was composed. In the eighth and seventh centuries BCE, the Greeks began to interact much more frequently with their Mediterranean neighbors, and these older civilizations had a powerful influence on Greek culture. For instance, the Works and Days strongly recalls the “wisdom literature” that was common in the East: compare the Sumerian Instructions of Šuruppak, the Akkadian Counsels of Wisdom, Egyptian instructional literature, and the Hebrew Book of Proverbs. Hesiod’s use of parable and allegory—for example, the fable of the hawk and the nightingale[12]—has also been interpreted as having an Eastern touch.

Synopsis

The Works and Days is a varied text. It is framed as Hesiod’s advice to his brother Perses on how he might best lead a hard-working, honest life.

Proem (1–10)

The Works and Days begins with an introductory hymn or invocation (called a “proem”) praising Zeus. Hesiod then addresses his project to his brother Perses.

The Two Strifes (11–41)

Hesiod describes two “Strifes” (both personified by a goddess named Eris): a bad Strife who causes conflict, and a good one who inspires hard work. The lazy, unscrupulous Perses is urged to forsake the bad Strife and follow the good one.

The Myth of Prometheus and Pandora (42–105)

Hesiod describes the origins of hard work and suffering: after the Titan Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to mortals, Zeus punished them by sending Pandora, the first woman, to unleash all the evils of the cosmos upon them.

Red-figure calyx-krater showing the creation of Pandora, attributed to the Niobid Painter (ca. 460–450 BCE)

British Museum, London / ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0The Myth of the Races (106–201)

Hesiod traces the progression of mortals through five races (or ages): a golden race, a silver race, a bronze race, a race of heroes, and an iron race. The iron race—the one in which Hesiod is living and writing—is presented as an era of toil and injustice.

Justice and Work (202–334)

Hesiod stresses the value of behaving justly and working diligently. He warns that Zeus punishes the unjust.

Social and Religious Advice (335–80)

Hesiod gives some general advice on proper religious behavior as well as how to deal with one’s neighbors.

Farming Advice (381–617)

Hesiod gives detailed practical advice for farmers to follow throughout the year.

Sailing Advice (618–93)

Hesiod gives very basic advice on sailing, mostly quoting the authority of others.

Social Advice (694–723)

Hesiod gives further advice on dealing with other people.

Religious Advice (724–64)

Hesiod gives further advice on proper religious behavior.

The Days (765–828)

The final section provides a detailed calendar or almanac of days that are favorable or unfavorable for various activities. This is sometimes thought to have been a later addition to the poem.

Style and Composition

The Works and Days is generally thought to have been composed after the Theogony, the other epic attributed to Hesiod. This is because Hesiod begins the Works and Days by admitting he made a mistake in an earlier poem when he said there was only one goddess of strife[13]—seemingly a reference to the Theogony, where Hesiod does indeed claim there is only one Strife.[14] Since the Works and Days is able to allude to the Theogony, it must be the later of the two poems.

The Works and Days is also seen as more linguistically and stylistically refined than the Theogony, suggesting that it represents the work of a more mature poet.

Like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the Works and Days adheres to the basic conventions of Greek epic poetry, employing dactylic hexameter and an elevated and artificial linguistic diction, which does not appear to have corresponded to any spoken dialect of ancient Greek.

Unlike Homer’s epics, however, the Works and Days is not a narrative poem. While it does include narrative elements (like the myth of Pandora), it is more accurately classified as a didactic poem—that is, a poem that sets out to teach the reader about something. In this case, the “something” ranges from farming and sailing to proper religious behavior.

Terracotta figurine of a plowman from Thebes in Boeotia, Greece (ca. 600–575 BCE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5Themes

The two central themes of the Works and Days are work and justice. The poem is presented as a guide for the author’s brother, a man named Perses, who, with the help of “bribe-swallowing lords,”[15] seized more than his fair share of the family inheritance. But Perses sometimes appears to be little more than a literary device, with his failings constantly changing to suit the context and needs of the author.[16]

Hesiod has much to say in this didactic poem, and much of it is unsavory. In the Works and Days, as in the Theogony, Hesiod comes across as a curmudgeonly, pessimistic farmer with conservative ethical and religious values and a strong distaste for women. The author viciously attacks idleness and praises hard work;[17] he sees life as suffering, much of which he blames on women;[18] and he insists that the gods always see and promptly punish injustice.[19] Often, Hesiod says his piece directly; other times, he uses parables or allegories to get his point across.

As in the Theogony, the justice of Zeus is represented as the ordering principle of the cosmos. Mortals must work hard and behave justly because it is Zeus’ will; anyone who disobeys Zeus will bring righteous punishment down upon their head. This, it seems, is the central point of the poem, and what Hesiod wants to teach his wayward brother Perses.

The Works and Days is full of folksy sayings and advice. Some of these tidbits are quite sensible and continue to circulate in some form today. For example, Hesiod’s “it is better to have your stuff at home”[20] has become “there’s no place like home”; “do not put your work off till to-morrow and the day after”[21] has become “don't put off until tomorrow what you can do today”; “observe due measure: and proportion is best in all things”[22] has become “moderation in all things”; and so on. But other passages are more difficult to interpret, as, for example, when Hesiod muses on “how much more the half is than the whole.”[23]

Some parts of the Works and Days continue to stump scholars. For example, Hesiod first explains the sufferings of mortals with the myth of Pandora, but immediately afterwards offers a different explanation based on the Myth of the Races. It can also be difficult to discern the unity of the Works and Days, which is at once a farmer’s guide, a sermon on hard work and justice, and a collection of miscellaneous advice and sayings. But the text remains indispensable to our understanding of the ancient Greek world.

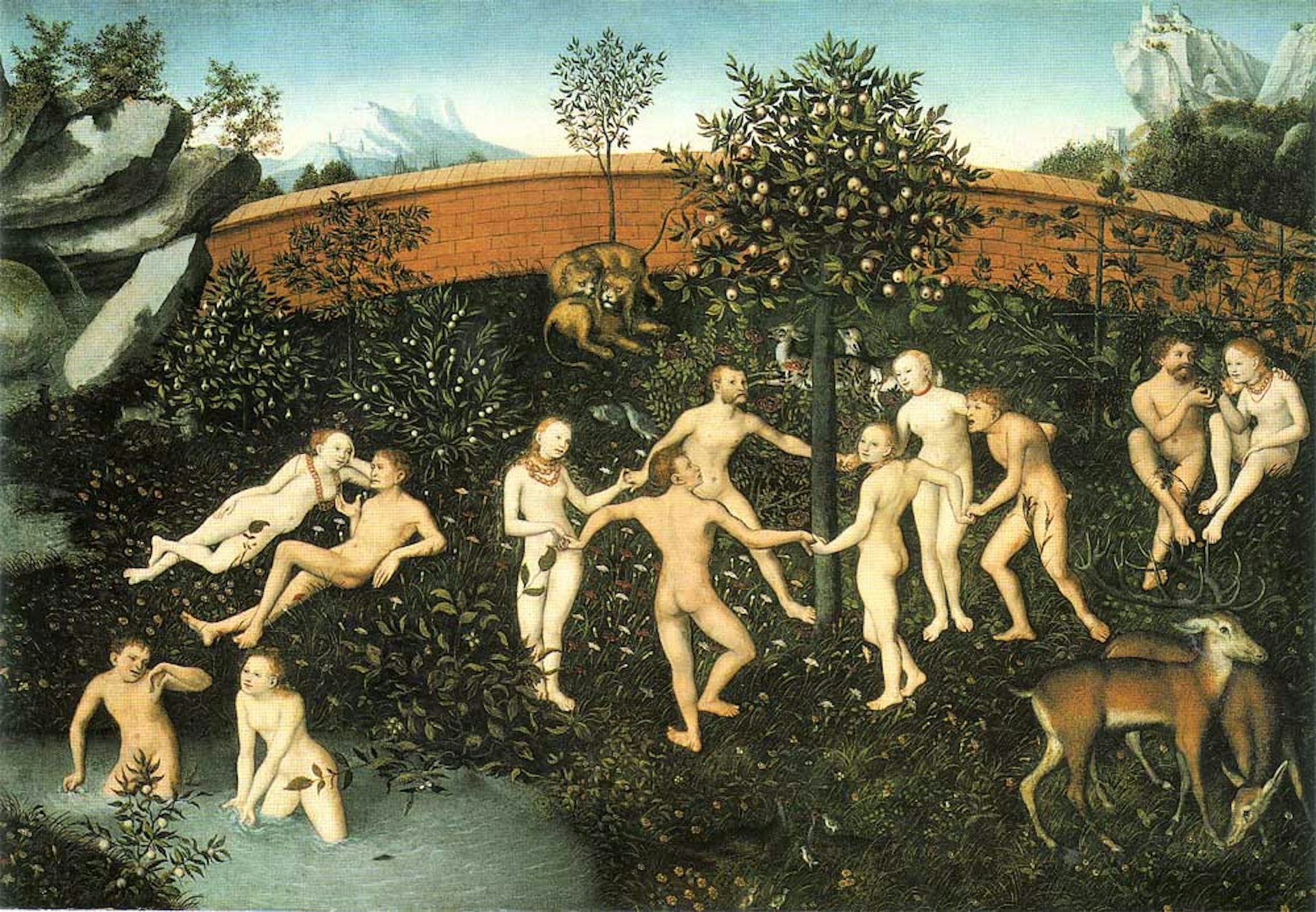

The Golden Age by Lucas Cranach the Elder (ca. 1530)

Alte Pinakothek, MunichPublic DomainReception

Hesiod was extremely influential in antiquity. His works, together with Homer’s, were considered the foundational literary and religious texts of the Greeks (and sometimes also of the Romans). Indeed, every ancient poet—from those, like Archilochus, who lived just after Hesiod, to imperial Roman poets like Virgil, Ovid, and Statius—can be said to have been influenced in some way by Hesiod.

Though Hesiod’s popularity waned during the European Middle Ages, the Works and Days was still sometimes admired for its ethic of hard work and honesty. Moreover, the Renaissance brought some renewed interest in Hesiod. The Pandora of the Works and Days became an especially popular subject for artists, featuring in the works of Jean Cousin the Elder, John William Waterhouse, Gabriel Rossetti, and many others.

Today, Hesiod is not as familiar in modern pop culture as Homer. The Works and Days in particular, with its heavy focus on farming, is often deemed of little interest to an increasingly urbanized world.

Translations

There have been numerous translations of Hesiod’s Works and Days (usually grouped together with the Theogony). The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful translations:

Evelyn-White, H. G., trans. Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914: A rather old-fashioned prose translation. Can be found in the public domain and thus remains an accessible option.

Lattimore, Richmond, trans. Hesiod: The Works and Days, Theogony, The Shield of Herakles. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959: Old but still highly-regarded translation in non-metrical, non-rhyming verse.

Wender, Dorothea, trans. Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days; Theognis: Elegies. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973: Readable verse translation, complete with brief commentary. The volume includes a translation of the poetry of Theognis.

Athanassakis, Apostolos N., trans. Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Shield. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983: Readable free verse translation with commentary.

Frazer, R. M., trans. The Poems of Hesiod. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983: Readable and accurate verse translation with commentary.

West, Martin L., trans. Hesiod: Theogony and Works and Days. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988: Prose translation that is very true to the original, produced by one of the most important scholars of Archaic Greek literature. Includes commentary.

Lombardo, Stanley, trans. Works and Days and Theogony. Hackett Classics. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993: Lively, rather folksy verse translation with added commentary.

Hine, Daryl, trans. Works of Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005: Readable, accurate, and annotated translation replicating the verse of the original (dactylic hexameter). The volume includes a translation of the Homeric Hymns.

Most, Glenn, trans. Hesiod, Vol. 1: Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006: A very accurate, readable new prose translation, replacing Evelyn-White’s older translation in the Loeb Classical Library series.

Schlegel, Catherine, and Henry Weinfield, trans. Theogony and Works and Days. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006: Unique translation employing rhyming iambic heptameter couplets. Flows well but is not always faithful to the original. Includes commentary.

Johnson, Kimberly, trans. Theogony and Works and Days: A New Critical Edition. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2017: Musical verse translation in bilingual edition that carefully seeks to preserve the structure of the original. Includes commentary.

Powell, Barry, trans. The Poems of Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, and the Shield of Heracles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017: Accessible verse translation, complete with helpful annotations.