Vishnu

Overview

As the preserver god, Vishnu keeps the cosmos running smoothly, ensuring that everyone and everything is in its proper place. He sends his avatars to earth in order to restore dharma, the righteous order of the universe, whenever it is threatened.[1] Often this threat takes the form of some demon or titan who tries to overthrow the rule of the gods. Famous examples of Vishnu’s avatars include Rama and Krishna, heroic figures of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata who are worshipped in their own right.

An intricately carved ivory shrine depicting the dashavatara, or ten avatars of Vishnu. ca 1800

National Museum, New DelhiPublic DomainOther avatars serve as primordial creators and shapers of the world, such as the boar avatar, Emusha, who dredges up the earth from the cosmic ocean and divides it into continents.

Etymology

According to Monier Monier-Williams, the name “Vishnu” probably derives from the Sanskrit root √viṣ, meaning “to work, perform, rule, subdue.”[2] Although he renders “Vishnu” as “Worker,” he acknowledges the common translation of the name as “the All-Pervader”—perhaps in reference to the widespread adjective vishva, meaning “all-pervader, omnipresent,” ascribed to Vishnu in the Vishnu Sahasranama.

Pronunciation

English

Sanskrit

Vishnu or Viṣṇu विष्णु Phonetic

IPA

[VISH-noo] /’ʋɪʂɳʊ/

Alternate Names

Vishnu and his avatar Krishna loom large in the Mahabharata, which has a long hymn devoted to his names, titled the Vishnu Sahasranama (“The Thousand Names of Vishnu”). His most popular epithets include:

Hari (हरि), “Carrying [Away]”

Narayana (नारायण), “He Whose Abode is Water”

Prajapati (प्रजापति), “Lord of Progeny”

Vasudeva (वासुदेव), “Son of Vasudeva”[3]

Attributes

One of the features shared by all of Vishnu’s avatars is blue skin. His vehicle is Garuda, the semi-divine king of the birds. Vishnu is often depicted holding a mace, a lotus, a conch shell, and his favorite weapon, the discus.

Family

According to Vaishnava traditions of Hinduism, Vishnu stands as the supreme god and is self-born (svayambhu), without a mother or father. This feature is shared with Shiva in Shaivite traditions. Vishnu’s wife is Lakshmi, goddess of fortune, prosperity, and wealth.

Vishnu reclining on the great serpent Shesha and floating on the cosmic ocean. Brahma is born from a lotus growing from Vishnu's navel. As he awakens between cosmic ages, Lakshmi massages his feet, ca. 1800 CE.

The Walters Art MuseumCC0Family Tree

Consorts

Wife

- Lakshmi

Mythology

Avatars

Vishnu is known for his frequent use of avatars in his quest to restore the cosmic order. The number of avatars varies between ten, twelve, and twenty-two; the ten most popular are detailed below. They run the full spectrum of the cosmic timeline, appearing at the creation of the earth as well as at the end of the current cosmic cycle.

The typical order in which the avatars appear shows a development from animal to human. The first three avatars are varying types of aquatic or semi-aquatic animals, followed by Narasingha (literally “Man-Lion”). The rest are humans—all male.

Matsya the Fish

Long ago, a righteous king named Manu performed great austerities for millions of years. In return, the creator god Brahma granted him a blessing. Rather than asking for invincibility (a common wish among demons), his request was far more selfless. He bowed respectfully and said, “I want only one thing from you, the ultimate boon: make me the protector of all standing and moving creatures when the dissolution happens.”[4]

It was not long before the need for his protection grew dire. As the king made water offerings to the ancestors, a single small fish fell into his hands. Only a day after he had taken the fish into his care, it grew and cried out for a bigger container. After three days, the new bowl was also too small for the fish. Soon it outgrew a well and even a pond. Now a league in length, it cried out, “Save me, save me, excellent king!” But the river Ganges itself could not contain its bulk, and soon the entire ocean was nothing more than a pool in comparison.

Now at the end of his wits, Manu saw the fish for who he really was: “Are you some sort of demon, or are you Vasudeva [Viṣṇu]? How could you be anyone else, such as you are? Now I recognize you, the lord, in the form of a fish! O Keśava, you have fooled me indeed; O Hr̥ṣīkeśa, Jagganātha, Jagaddhāma, praise be to you!”

Now recognized, Vishnu spoke in the form of the fish and told Manu that at the dissolution of the world, a great flood would wash away all things. But the gods had crafted a boat, and Manu was to gather all creatures—those born from eggs, plants, and sweat, as well as those born living—and bring them aboard. Manu was then to fasten the boat onto the fish’s horn.

In the lead-up to the dissolution of the world, a hundred-year famine broke out, followed by searing heat and solar flares, and everything burned. Seven clouds burst open and flooded the world, and all the seas merged into one violent ocean. Only Manu, a handful of gods (Soma, Surya, Brahma, and Vishnu), and the seer Markendeya survived. Throughout all this ruin, Manu gathered the world’s plants and animals onto his boat.

Once all were safely aboard, Vishnu guided the boat and told Manu the secrets of the cosmos and the creation of the world. At the beginning of the new age, the Krita Age, Manu reigned as lord of all things on earth.[5]

Kurma the Tortoise

When Vishnu assumed the form of Kurma the tortoise, his goal was not to slay a demon or right a wrong. Instead, he wanted to help the gods achieve immortality by churning the cosmic ocean. In short, the gods and demons decided to set aside their differences and work together in order to create amrita, the nectar of immortality. To do so, they needed to churn the cosmic ocean just as they would churn milk in order to make butter.

But no ordinary churning tools would do: for this, they uprooted the great mountain Mandara, with all its trees, herbs, and animals, and plunged it into the ocean. They then wrapped the giant snake Vasuki around the mountain, with the gods taking one end and the demons the other, and began to twist the mountain and stir the ocean.

Their task was an arduous one, for the mountain’s great size meant that it would not stay afloat. To remedy this problem, Vishnu took on the form of Kurma the tortoise and supported the mountain with his great shell. The gods and demons were then able to complete their task and create the sacred amrita.[6]

Emusha the Boar

Long ago, Vishnu took on the form of a boar, variously named “Emusha,” “Varaha,” and “Prajapati”—the first avatar that was not purely aquatic. His great deed was one of creation: when all the world was still just an ocean, he discovered the earth underneath the waters, in the underground regions of hell.

The earth goddess saluted him reverently and implored him to raise her up, as he had in earlier ages when he took on the avatars of a fish and a tortoise. According to the Vishnu Purana, she praised him as the sole creator, preserver, and destroyer of the world and revealed that he variously takes the form of Brahma (traditionally known as the creator god), Vishnu (the preserver god), and Rudra (another name for Shiva, the destroyer god).[7]

She continued with her prayers, saying,

No one knoweth thy true nature; and the gods adore thee only in the forms it hath pleased thee to assume. … Whatever may be apprehended by the mind, whatever may be perceived by the senses, whatever may be discerned by the intellect, all is but a form of thee. I am of thee, upheld by thee; thou art my creator, and to thee I fly for refuge. … Thou art sacrifice; thou art the oblation[8] … thou art the Vedas … The sun, the stars, the plants, the whole world; all that is formless, or that has form; all that is visible, or invisible; all, Purushottama,[9] that I have said, or left unsaid; all this, Supreme, thou art.[10]

Vishnu (as Emusha the boar) then raised up the earth with his tusks, placed it carefully on top of the water, and spread it in all directions so that it grew from the size of a single hand span to the great mass it is now. Because the earth was so stretched, it was able to float on the water. For this reason, the earth is also called “Prithivi,” or “The Extended One.”

Vishnu as Emusha then took hold of the earth, raised up mountains, and carved out valleys. Since the world had been divided into seven continents in earlier cosmic ages, he re-created these continents and formed divisions between the earth, heavens, hells, and ether.

Emusha later slew the demon Hiranyaksha, sparking a hatred between Vishnu and Hiranyaksha’s brother, Hiranyakashipu (see below).

Narasingha the Man-Lion

Vishnu took the form of Narasingha (literally “Man-Lion”) in order to slay the demon Hiranyakashipu. The demon had once performed a great deal of austerities and in return was granted a blessing: invincibility. He could not be slain by god, man, or beast, on the ground or in the sky.[11]

With his invulnerability, he fought the gods and reestablished demons as rulers of the cosmos. Moreover, he banished the gods and took for himself whatever sacrifices or ritual offerings were meant for his foes.

Hiranyakashipu harbored a bitter grudge against Vishnu, for it was Vishnu (in the avatar of a boar) who had slain his brother, Hiranyaksha, many ages past. But his son, Prahlada, was a devout worshipper of Vishnu and openly praised the god as being even greater than his father.

Eventually, Hiranyakashipu grew so angry at his son’s worship that he tried to kill him several times. But each time, Prahlada’s devotion—and Vishnu himself—saved him from certain death.

When Hiranyakashipu sent his servants to kill his son, their weapons had no effect; when snakes bit Prahlada on every inch of his body, he felt no pain; elephants’ tusks came back blunted when they tried to gore him.

“Behold,” Prahlada exclaimed, “the tusks of the elephants, as hard as adamant, are blunted. But this is not by any strength of mine. Calling up Janārdana is my defence against such fearful affliction.”[12] The demon king tried to poison him, threw him out of a window, and cast him into the sea tied down with weights, but to no avail. His son shook off every attempt and returned to preach about the omnipresent Vishnu.

By this point, Hiranyakashipu had reached his wits’ end and asked his son why Vishnu was not visible in a pillar in his grand hall if the god was everywhere at all times. He then rose and struck the pillar—and to his shock, the god did appear. Narasingha, the lion-man avatar, burst out of the pillar and enacted his final, brutal revenge on the demon for defeating the gods: he ripped Hiranyakashipu’s chest open with his claws.

Stone image of Narasingha slaying Hiranyakashipu, ca. seventh century CE.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBecause Narasingha was neither man, nor beast, nor god, he was able to slay the demon despite his seeming invulnerability. Moreover, as he ravaged Hiranyakashipu, Vishnu kept the demon on his thighs so that he was neither on the ground nor in the sky.

Vamana and the Three Strides

One of the most important tales of Vishnu goes back to Vedic times and deals with the neverending tug of war between the gods and demons for control of the cosmos. The story appears variously in the Rig Veda and the Shatapatha Brahmana.

In the Rig Veda we find a series of verses proclaiming the wonders of Vishnu:[13]

I will proclaim the heroic deeds of Viṣṇu, who measured apart the earthly realms, who propped up the upper dwelling place, when the wide-striding one stepped forth three times.[14] Viṣṇu is praised for his heroic deed, he who stayed in the mountain wandering cruelly like a wild beast. All creatures dwell in his three wide steps.

Let the resounding prayer go forth to Viṣṇu who lives in the mountains, the wide-striding one, the bull who alone measured apart with three steps this far extended dwelling-place.[15]

The Vedic concept of creation is based on measuring out and dividing the elements, a theme seen earlier when Vishnu (as a boar) spread out the earth and divided it into continents.[16]

Later Hindu literature, including the Shatapatha Brahmana and Vayu Purana, expands on this event and has Vishnu taking three strides in the form of Vamana the dwarf.[17] During the Treta Age long ago, the demons got the upper hand against the gods, and the demon king Bali reigned supreme over the cosmos. To restore the gods’ place, Vishnu’s avatar appeared, diminutive and unintimidating, with short arms and legs. He strode into Bali’s court while the demons were performing a sacrifice[18] and requested a blessing:

“O king, you are the lord of the three worlds,” said Vamana. “Everything is in you. It behoves you to grant me (the space covered by) three paces.”[19]

Bali accepted this request, not thinking much of the short Vamana. But his amusement turned to dread as the seemingly insignificant dwarf grew to a monstrous size: “But the dwarf, the lord, stepped over the heaven, the sky, and the earth, this whole universe, in three strides.”[20] And with those three strides he assumed control of the cosmos and banished Bali and all the demons with him to hell, routing them in all directions. With the cosmos in the hands of the gods, Vishnu anointed Indra as their king.

The version in the Shatapatha Brahmana also depicts Vishnu’s incredible expansion but does away with the three strides. In this version, the demons were dividing the cosmos amongst themselves and measuring distances with the hides of oxen. The gods gathered among them to ask for their own share and placed Vishnu (again as a dwarf) on an altar for their sacrifice. Seeing the short god, Bali arrogantly proclaimed that the gods could have only as much as Vishnu could rest on.

In response, the clever gods worshipped Vishnu and enclosed him in each direction with a different poetic meter: the Gayatri meter in the south, the Trishtubh meter in the west, the Jagati meter in the north, and Agni, the god of fire himself, in the east. After worshipping him until they were exhausted, the gods soon controlled the cosmos.

Parashurama

Vishnu’s avatars usually descend to earth to right a wrong brought about by a powerful demon: Rama slays Ravana, Narasingha slays Hiranyakashipu, Vamana takes his three strides and wrestles control of the cosmos from the demon king Bali, and so on. In contrast, Parashurama, or “Axe-Bearing Rama,” comes to earth to humble the Kshatriya warrior caste for their mistreatment of Brahmins.[21]

At one time, King Arjuna[22] of the Kshatriya caste honored and gave sacrifices to Dattatreya, a divine sage. In return, he was granted invincibility, a thousand arms, wealth, fame, strength, and mastery of Yoga.[23]

Meanwhile, Parashurama was born into the family of the pious Brahmin Jamadagni and his wife, Renuka. Jamadagni had little of value except for an excellent sacrificial cow; his wealth consisted of the vast amount of tapas, or asceticism, that he had accumulated over the years from a life of sacrifice.

One day the Kshatriya king went out hunting with his army, servants, and attendants and came across Jamadagni’s hut. The Brahmin graciously received the king and his men and served them milk, butter, and other forms of dairy from his sacrificial cow. But the king, upon seeing the cow, judged its worth to be greater than all his worldly wealth. Consumed with greed, he seized the animal and led it back to his capital city.

Luckily for the king, Parashurama had been away during his stay. But when the Brahmin’s son returned and learned of what had happened, he resolved to get his father’s cow back, no matter the price. Seizing his bow and axe, he set off.

Arjuna the king returned to his city just in time to find Parashurama waiting for him, his terrible axe in hand. Vishnu’s avatar slew the king’s army then and there, hacking away not only at the men but also at the horses, chariots, and elephants. Soon, only Arjuna was left, but the king was not to be trifled with, for he still had a mighty blessing and a thousand arms. With those arms, he loosed hundreds of arrows at once at Parashurama. But it was no use: he fell as easily as the rest of his army.

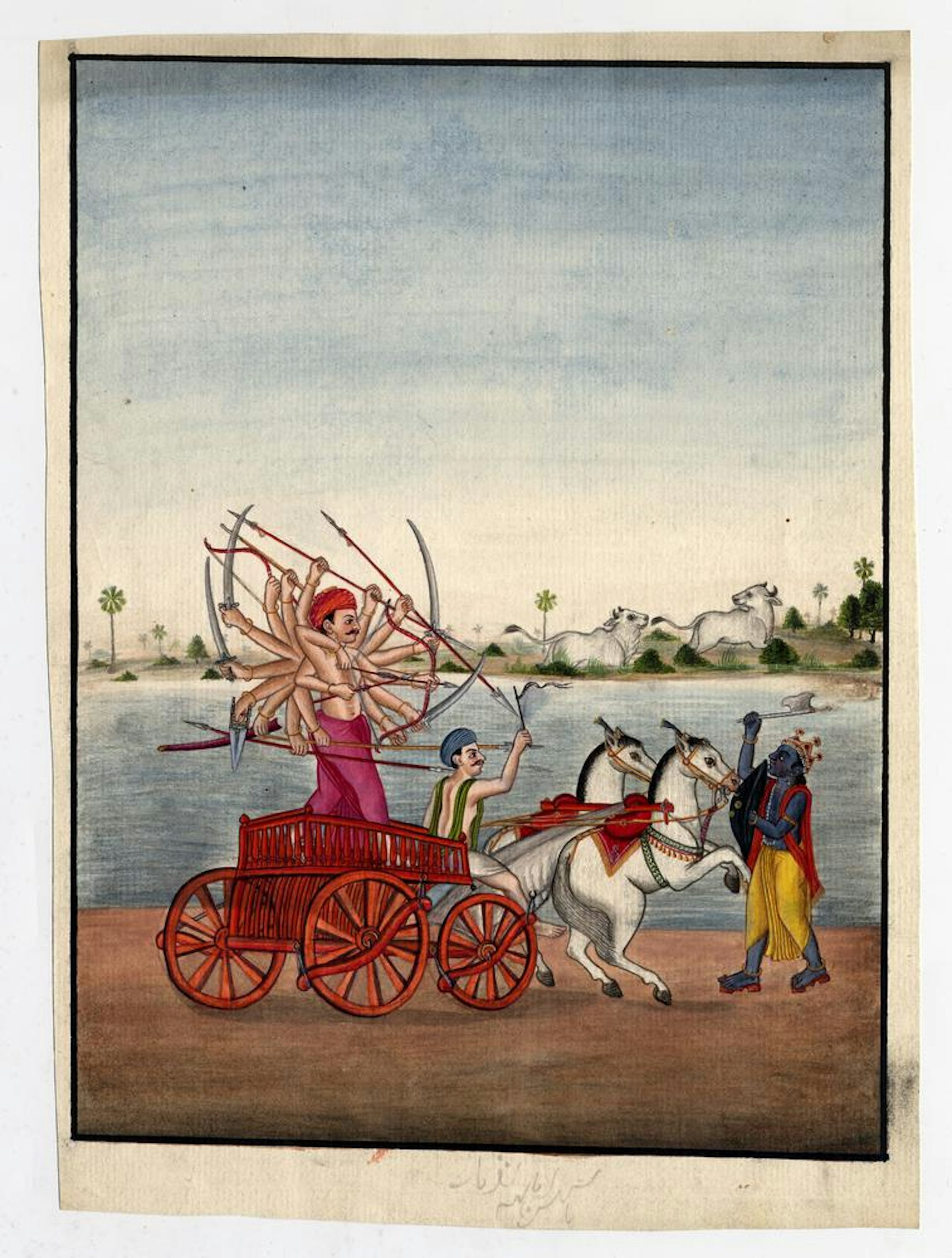

Parashurama, notable for his blue skin and war axe, in battle with the many-armed Kshatriya king Arjuna for stealing his father's cow, ca. 1880.

Trustees of the British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0For a time, Parashurama and his family prospered with the return of the cow. But Arjuna’s sons still lived; though they had fled in terror at Parashurama’s onslaught, they now wanted revenge for the death of their father. Sneaking into Jamadagni’s hut while Parashurama was away, they slew the Brahmin, thus continuing the cycle of hatred and revenge.

In response, Parashurama broadened his hatred to all members of the Kshatriya caste. He returned to the city once more, slew all the Kshatriyas with his terrible battle axe, and made a mountain of their heads in the city center. Indeed, in his rage he wiped out the warrior caste not just once but twenty-one times and “filled nine lakes in Samantapañcaka with their blood.”[24]

In the end, Parashurama was able to bring back his father. He rejoined Jamadagni’s head to his body and gave sacrifices to himself, for he was none other than Vishnu’s avatar. He also bathed in the Sarasvati River to cleanse himself of all guilt and sin. Jamadagni then rose once more and eventually became a great sage.

Rama

Vishnu descends to earth and is born as Rama in order to slay the demon Ravana and restore dharma. Rama is the son of Dasharatha, the husband of Sita, and the hero of the epic poem the Ramayana.

Krishna

Perhaps the most popular avatar of Vishnu, Krishna looms large over the epic poem the Mahabharata and plays a central role in the Bhagavad Gita. Like Rama, Krishna is a divine hero-prince. Unlike most other avatars, however, he often acts as a trickster figure who steals butter and plays pranks, especially during his youth.

The Buddha

At one time, the war betweens the devas and daityas (gods and demons) raged in favor of the demons, and the gods were driven back from their strongholds. They reasoned that the demons owed their skill in battle solely to their righteous adherence to the Vedas and to the sacrifices they drew power from.

To combat this, the gods supplicated themselves before Vishnu, saying, “They take pleasure in the duties of their own class, and they follow the path of the Vedas and are full of ascetic powers. Therefore we cannot kill them, although they are our enemies, and so you should devise some means by which we will be able to kill the demons, O lord, soul of everything without exception.”[25]

Vishnu’s solution to their prayers was to emanate a magical illusion from his body in the shape of an ascetic—bald, naked, and carrying peacock feathers—whom he named “the Buddha.”[26] This naked ascetic, Vishnu said, will walk among the demons and give them false teachings. Being thus deluded, the demons will fall from the righteous path of the Vedas and Brahmins and be fair game for slaughter.

His plan was a rousing success, for the magical illusion convinced many of the demons to abandon the Vedas, give up sacrificing animals, and take up Buddhism, Jainism, and other ascetic traditions. In the battles that followed, the demons suffered terrible defeats without the protection provided by sacrificing and honoring Brahmins.

This penultimate avatar differs from the rest in that Vishnu is not born as a mortal (unlike Rama and Krishna, for example). Instead, the Buddha is strictly a magical delusion (māyāmoha) summoned by Vishnu’s magic. In fact, Vishnu’s delusion worked a little too well, convincing many humans to convert to Buddhism and Jainism. In this way, Vishnu uncharacteristically subverted his own grand purpose of restoring the righteous order of the universe.[27]

Kalkin

Vishnu’s final avatar, Kalkin, has yet to arrive. According to the Vishnu Purana, Vishnu will appear at the end of the present Kali Age when humanity has degenerated from its current state. In that distant time, people will live mostly in mountainous areas, wear clothes made from bark, and live on honey, flowers, roots, and vegetables. Kalkin will be born in the village of Shambhala to the Brahmin Vishnuyashas (Viṣnu-yaśas, “Glory of Vishnu”).[28]

With unlimited power and martial might, Kalkin is predicted to wipe out the barbarians and non-Hindus and reestablish all things in their proper order. When the minds of all people are thus restored and no longer degenerate, those who are left will serve as the seeds for future generations. The cycle of existence will then reset, beginning again in the Krita Age.

Wendy Doniger claims that the passage detailing Kalkin’s birth was written around the first few centuries CE, “a time when millennial ideas were rampant in Europe” and when Scythians, Parthians, and other nomadic peoples swept through northwestern India and established kingdoms there.[29] Anxiety about nomadic migrations is reflected in Kalkin’s supposed purpose of wiping out barbarians and non-Hindus, as many of the nomadic peoples and Indo-Greeks before them were followers of Buddhism.

Origins

Just as Shiva (in the form of his prototype, Rudra) can be traced back to the Vedas, so too can the preserver god, Vishnu. Today he has grown into one of the most worshipped gods in the Hindu pantheon, but his Vedic beginnings are far more humble. He often appears alongside other gods, such as Indra; it was Vishnu who helped Indra slay the great demon serpent Vritra, and he is sometimes called “Upendra” (“Little Indra”) and “Indranuja” (“Indra’s Little Brother).[30]

Although nowhere near as prevalent as Indra, Agni, and other Vedic gods, Vishnu is mentioned by name in a handful of cases.

Some of the Vedic mythology in question, such as that of Vishnu and the three strides that spanned the whole world, we have seen already in connection with his avatar Vamana. Monier-Williams argues that these three strides suggest a relationship with the sun, saying that the event can be “explained as denoting the threefold manifestations of light in the form of fire, lightning, and the sun, or as designating the three daily stations of the sun in his rising, culminating, and setting.”[31]

Wendy Doniger notes that “although only a small proportion of the mythology of Viṣṇu can be traced back to the R̥ig Veda—hardly any more than that of Śiva—Viṣṇu is a far more straightforward, orthodox god; those elements of proto-Indian worship which were assimilated to his cult are generally more benevolent, human, and conventional tha[n] those of Śiva.”[32]

Assimilation does indeed seem to be a key feature of Vishnu’s development, as is the case with many Hindu gods. His use of avatars highlights this: many of the avatars may well have begun as fully independent beings with no connection to Vishnu at all. But as time went on, Vaishnava sects began to adopt or assimilate more and more of these figures, leading to the current collection of avatars.

Worship

Temples

As one of the most popular gods, Vishnu has numerous temples throughout South and Southeast Asia. Given the sheer quantity of avatars and different forms that Vishnu assumes, these temples are dedicated to a wide variety of figures, but all can still be considered Vaishnava.

The Sri Ranganathaswami Temple in Tamil Nadu, India, with multitudes of colorful gods and figures carved onto the outside. It stands as one of the biggest Vaishnava temples in the world and is built in classic Dravidian style.

Tamil Nadu TourismThe Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple in Srirangam, Tamil Nadu stands out among Vaishnava temples due to its riot of colors. It is dedicated to the reclining form of Ranganatha, a form of Vishnu.

Angkor Wat, the well-known Buddhist temple complex in Cambodia, was originally built as a temple to Vishnu by Suryavarman II in the late twelfth century CE. The Khmer dynasty of the time practiced a variety of Indian traditions and paid special homage to Vishnu, Shiva, and the Buddha.

Angor Watt in Cambodia, built originally as a temple to Vishnu in the twelfth century CE, has since been converted to a Theravada Buddhist temple.

UNESCOCC BY-SA 3.0Pop Culture

Vishnu stands as one of the supreme gods in the Hindu pantheon, still worshipped and celebrated by millions every year. As such, depictions of Vishnu and his many avatars are common throughout South and Southeast Asia: statues, movie posters, street art, plays, and television series feature him prominently.

The live-action television series Vishnu Puran (2000) features Vishnu as the main character, showing him throughout the eons as he sends his avatars out into the world to re-establish dharma.