Tyr

Overview

The one-armed god of the Norse pantheon, Tyr was a member of the Aesir tribe who represented war and bloodshed. Somewhat paradoxically, he was also known as a bringer of justice and order. Tyr’s contradictory nature stems largely from a lack of information about him. Mentioned only sparingly in the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda, the works that form the backbone of Norse mythology, Tyr was best known for wrestling the monstrous hound Fenrir and losing his arm in the process.

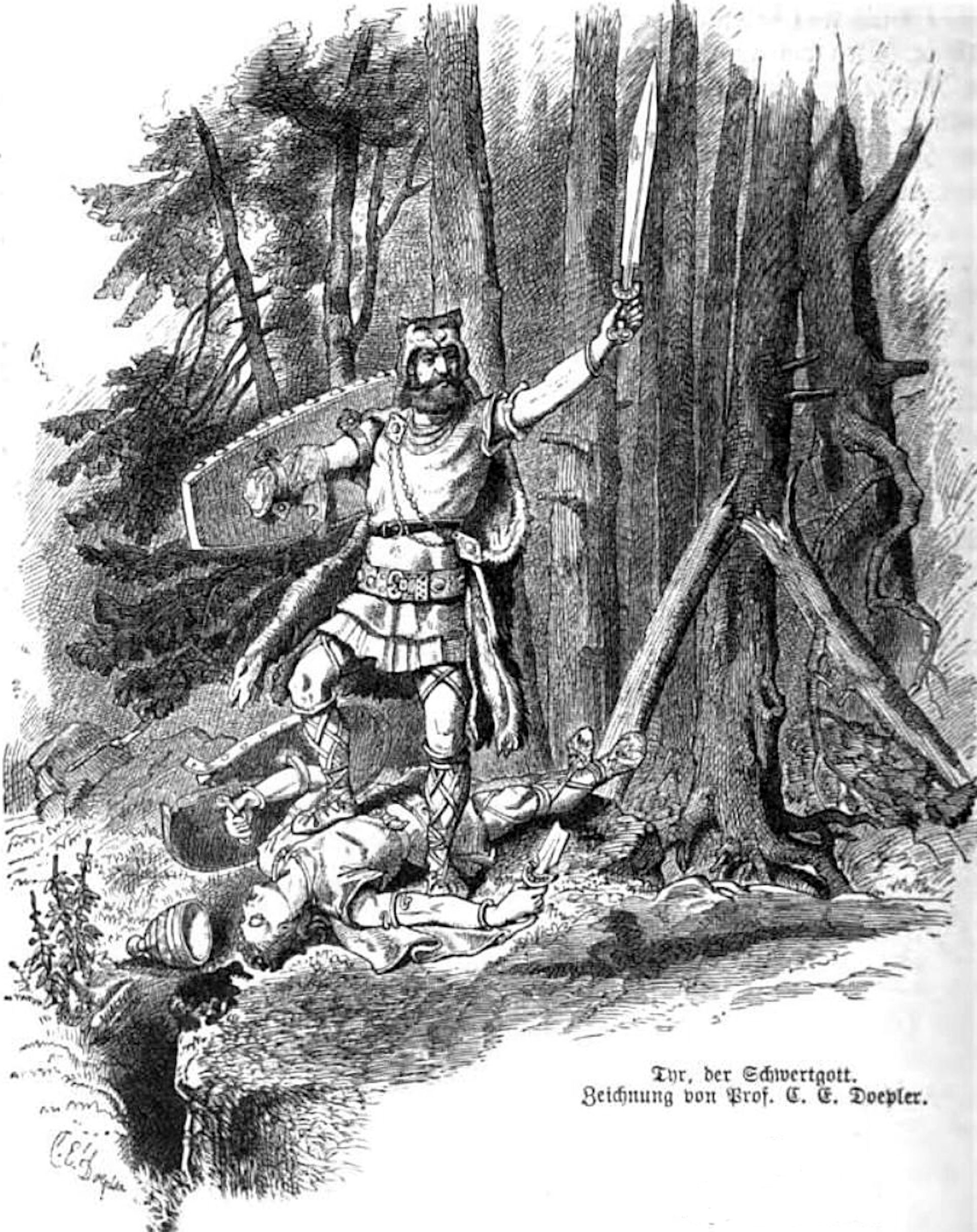

Tyr, with his severed arm in the shield straps and sword raised, vanquishes a foe. Image from Wilhelm Wägner, Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden (Leipzig and Berlin: Otto Spamer, 1882), p.162.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOften associated with Norse mythology, Tyr actually originated as a Germanic deity during the early centuries of the common era. While he was a powerful figure in Germanic religion, by the Viking era (800–1100 CE) his importance had waned. His former prominence among the Germanic peoples and the Norse, however, was attested by the use of his name for the letter “T” of the runic alphabet, as well as for the word Tuesday, which meant “Tyr’s day.”

Etymology

The name “Tyr,” meaning “a god” or even “the god,” stemmed from the Proto Indo-European *dyeus-, by way of the Proto Germanic *Tiwaz, meaning “god or deity.” This was the same root used in the names of Zeus, king of the Greek gods, and Jupiter, king of the Roman gods. Because this word was reserved for the most powerful of deities, scholars have speculated that Tyr once held such a position. By the time the first Norse epics were recorded, however, Tyr’s importance had declined significantly.

Attributes

Tyr was a more than just a brave warrior—he was also a reliable source of wisdom and a champion of justice. These descriptions, admittedly, relied on brief mentions of the god in the Norse epics. The most detailed description of the god was derived from the Gylfaginning, a book of the Prose Edda by the thirteenth-century Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson. It read:

Yet remains that one of the Æsir who is called Týr: he is most daring, and best in stoutness of heart, and he has much authority over victory in battle; it is good for men of valor to invoke him. It is a proverb, that he is Týr-valiant, who surpasses other men and does not waver. He is wise, so that it is also said, that he that is wisest is Týr-prudent.[1]

Tyr’s most notable attribute was his missing right hand (or arm), generally depicted as being severed at the wrist or forearm. This missing limb had been devoured by Fenrir, the ravenous giant wolf sired by Loki and the jötunn Angrboda. Fenrir would later play a central role in Ragnarök.

Tyr with a sword and severed hand in a 1680 Icelandic edda manuscript

Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic StudiesPublic DomainFamily

Tyr was either the son of Odin, the “All Father” and king of gods, or Hymir, a giant from an obscure section of the Poetic Edda called the Hymiskviða (the “Lay of Hymir”). While the latter text omitted mention of Tyr’s mother, it identified his grandmother as a woman with nine hundred heads.

Most scholars have come to the consensus that Odin was Tyr’s true father. As Sturluson wrote in the Skáldskaparmál: “‘How should one periphrase Týr? By calling him the One-handed God, and Fosterer of the Wolf, God of Battles, Son of Odin.’”[2]

By virtue of being Odin’s son, Tyr was a half-sibling to the chief members of the Aesir tribe. Tyr’s half-siblings consisted of some of the most prominent figures in Norse mythology, including Thor, Baldur, Váli, and Vidarr, as well as Heimdall, Hermod, Bragi, and Hodr.

Family Tree

Mythology

Tyr and the Kettle of Giants

Tyr appeared as a central character in only two myths. He first appeared in the Hymiskvitha, an unfinished work, though he suddenly disappeared from the tale mid-narration. The story concerned Thor’s search for a fabled kettle—one large enough to brew prodigious quantities of ale. Tyr claimed that the kettle was in the possession of Hymir, a giant whom Tyr identified as his father.

The two gods traveled to Hymir’s home and found that the giant was away. Tyr’s grandmother was there, however, and urged them to hide lest they incur Hymir’s wrath. The gods found this to be sage advice, and took refuge in one of Hymir’s monstrous kettles. When Hymir finally arrived, he smashed a pillar where Tyr and Thor were hiding. The kettles were scattered instantly, and the gods found themselves exposed. Hymir grew fearful at the sight of the mighty Thor, and called for three oxen to be cooked for his guests. Thor ate two and took the other as bait, claiming he would use it when he went fishing with Tyr the next day. At this point, Tyr disappears from the story.

Tyr, Fenrir, and Ragnarök

Tyr was best known for losing his hand (or arm) to Fenrir, the giant wolf. This story, briefly recounted in the Gylfaginning, emphasized Tyr’s bravery, as well as his willingness to sacrifice for justice. Fenrir grew up in Asgard and lived among the gods, though only Tyr was brave enough to approach him. Knowing that Fenrir would play a critical role in Ragnarök, the gods played a “game” in which they would try to ensnare him. Fenrir always “won,” however, and broke his bonds each time. Seeking something that would confine Fenrir for good, the gods commissioned the crafty dwarves of Svartalfheim to construct a durable set of fetters, which they lovingly called Gleipnir.

Tyr sacrifices his hand to Fenrir in this Icelandic edda manuscript (1765-1766).

Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic StudiesPublic DomainWith Gleipnir in hand, the gods sought to trap the beast once more. The presented Gleipnir to Fenrir and challenged him to one final game.[3] When Fenrir saw how thin the bonds were, he grew suspicious, claiming that the gods were trying to deceive him. He only consented to the game after Tyr agreed to place an arm in his mouth. With this makeshift insurance policy in place, Fenrir allowed the gods to bind him. The great wolf struggled against his bonds, and for the first time found that he could not break them. Realizing that the gods did not intend to release him, Fenrir bit down on Tyr’s hand:

When the Æsir enticed Fenrir-Wolf to take upon him the fetter Gleipnir, the wolf did not believe them, that they would loose him, until they laid Týr’s hand into his mouth as a pledge. But when the Æsir would not loose him, then he bit off the hand at the place now called ’the wolf’s joint;’ and Týr is one-handed, and is now called a reconciler of men.[4]

The text also revealed Tyr’s fate during Ragnarök, the “twilight of the gods.” When the final battle between gods and jötunn commenced, Tyr would both slay and be slain by the wolf Garmr: “Then shall the dog Garmr be loosed, which is bound before Gnipa’s Cave: he is the greatest monster; he shall do battle with Týr, and each become the other’s slayer.”[5]

Pop Culture

The legacy of Tyr has been maintained in popular culture at least in part by the Faroese metal band Tyr. The band has explored Norse myths and themes in their music, having released albums such as How Far to Asgaard (2002), Eric the Red (2003), Ragnarok (2006), and The Lay of Thrym (2011).

Tyr’s greatest legacy, however, is the word “Tuesday.” Once known as “Tyr’s day,” the word has endured for centuries and is now more popular than ever.