Thor

Overview

A paragon of strength and masculine virility, the storm god Thor was the fiercest of Norse deities. He was the son of Odin, the “all-father,” and a member of the Aesir tribe of deities. Among his many abilities, Thor commanded storms and rain, and brought lightning and thunder. Due to his prodigious sexual appetite and his aptitude for impregnating women, Thor was also associated with fertility. He wielded a war hammer called Mjölnir, and was thought to have red hair and a red beard.

Brave, powerful, and righteous, Thor fully embodied the hero archetype. Where Odin and Loki skulked and schemed, Thor faced his problems with a hammer in his hand and violence in his heart. Whenever a fearsome beast or wily jötunn threatened their peace, the gods generally turned to Thor for intervention.

Mårten Eskil Winge, Thor's Fight with the Giants (1872). With Mjölnir in hand, Thor lays waste to the giants from his chariot, which is pulled by his goats Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr.

Nationalmuseum, Sweden Public DomainThor was an extremely popular figure and one of the earliest attested deities in the Norse pantheon. References to Thor were found going as far back as the first century CE, when Roman writings referred to him as Jupiter. Relics depicting Thor and his hammer were among the most common archaeological artifacts found in Northern Europe. His cult thrived during the Viking Period of northern European history (ca. 800 to 1100 CE), and his lore survived in the folk traditions of modern Germanic language speakers.

Etymology

The name “Thor” (Þórr in the Old Norse, thunar in Old Saxon) meant “thunder,” and was an obvious reference to the god’s alleged control of the phenomenon.

When the Germanic peoples adopted the Roman calendar in the early centuries of the Common Era, they replaced the day called dies Iovis (“the day of Jupiter”) with Þonares dagaz, or Thor’s day. In modern English, this name survives as “Thursday.”

Among the many epithets describing Thor were Atli (“the terrible”), Björn (“the bear”), Einriði (“the one who rides alone,” a reference to Thor’s tendency to act on his own), Harðhugaðr (“brave heart” or “fierce soul”) and Vingthor (“the thunder hurler”).

Attributes

Above all things, Thor was brave, strong, and fierce. Thor, in truth, loved fighting and rarely passed on an opportunity to engage in it.

Thor wore a magical belt called Megingjörd (literally “power belt”) that was said to double his already substantial strength. Thor’s chief was weapon was Mjölnir (“grinder” or “crusher”), a terrible war hammer crafted by dwarves in their subterranean caverns. Besides spitting thunderbolts and laying waste to obstacles and enemies, Mjölnir could also resurrect the dead—though apparently only in certain cases. In order to wield his mighty hammer, Thor wore iron gloves named Járngreipr (“iron grippers”). While these three items were the ones most associated with the thunder god, Thor also possessed a staff known as Grídarvölr; he seldom used it, however.

Thor kept company with his two servants, the twins Thjálfi and Röskva. He rode in a chariot pulled by the goats Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. Remarkably, Thor regularly slaughtered the goats and ate them, only to resurrect them with Mjölnir so that they could continue to pull his chariot—and fill his stomach!

Thor’s realm was the field Þrúðvangr in Asgard, where he built his oaken hall, Bilskirnir. The building was said to be the largest ever erected and featured a grand total of five hundred and forty rooms.

Family

Thor was the son of Odin, the chief of the Aesir deities and highest of all gods. While his mother was variously known as Jord (“earth”), Hlödyn, or Fjörgyn, in all cases she was identified as a giant, making Thor half-jötunn. Thor’s heritage provided an interesting contrast with his noted enmity for the jötnar. By way of Odin, Thor had many prominent half-brothers including Baldur, Váli, and Vidarr. Other half-brothers included Tyr, Heimdall, Bragi, and Hodr.

Wood carved illustration from Olaus Magnus's A Description of the Northern Peoples (published in Rome, 1555). The illustration pictures the three main gods of the Norse: Frigg on the left, Thor seated on the throne in the center, and an armored Odin on the right. The wood carving shows how much Norse mythology was altered through the centuries. Here it is Thor, the most popular of Norse deities, and not Odin who is depicted as a lord.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn the fullness of his manhood, Thor married golden-haired Sif, a goddess associated with faith, family, and fertility. With Sif, Thor had a daughter known as Thudr, who may have become a valkyrie. Outside his marriage, Thor had a regular lover, Járnsaxa. With his jötunn lover, Thor had a son named Magni (“strength”). He also had many casual lovers and one-night stands. At least one of these encounters produced a son, Módi (“courage”), though the boy’s mother was not identified in any surviving Norse texts.

Family Tree

Mythology

Probably the most adventurous of the Norse deities, Thor had a mythology full of exploits and escapades. Such adventures included battling with foul monsters, journeying to distant lands, and even dressing as a woman.

Origins

Norse mythology seldom provided details about the childhoods and early lives of its main deities. Thor followed this pattern, and emerged in the sources as a full-fledged god with his entire repertoire of powers at his disposal. Nevertheless, a few historical details served to illuminate to Thor’s emergence as a god of the Germanic people.

Marble figurine of Thor resting on his hammer (ca. 1827-1829) by Hermann Ernst Freund

National Gallery of DenmarkPublic DomainThe first mentions of Thor were found in Roman sources. There, Thor was identified as Jupiter or Jove, the Roman god of strength who hurled lightning bolts (Jupiter was, in turn, based on the Greek god Zeus). The Romans commonly referred to the gods of foreigners by the names of the Romans deities who most nearly approximated their characteristics. The Romans were right to note the similarities. A deeper look at European, Near Eastern, and even South Asian religions has revealed remarkable similarities between Thor and other thunder-hurling deities, such as the Celtic god Taranis and the Vedic deity Indra. Whatever his origin in Norse myth, Thor appeared historically as a local variant of an archetypal Indo-European deity whose origins could be traced back to the second millennium BCE.

Mjölnir, the Hammer of Thor

The story of how Thor got his hammer was told in Snorri Sturluson’s Skáldskaparmál of the Prose Edda, and began with the typical antics of Loki, who mischievously cut off all of Sif’s golden hair. Understandably angry at this slight, Thor “seized Loki, and would have broken every bone in him.” Loki promised to make amends, however, by traveling to Svartalfheim, the home of the dwarves located in the caverns beneath the earth (dwarves perished in the sunlight, and thus were always skulking underground).[1] There, Loki would find the dwarves’ master builders and ask them to construct a new head of hair for Sif.

True to his word, Loki traveled to the home of dwarves and found the sons of Ivaldi, master craftsmen who fashioned new hair for Sif and two other masterworks: the unbreakable ship Skidbladnir, and the deadly spear Gungnir. Loki did not return to the gods just yet, however, for he saw an opportunity and concocted a clever plan. He sought out the dwarf brothers Brokkr and Sindri and taunted them, claiming that they could never craft anything as perfect as the creations of the sons of Ivaldi. Taking the bait, the brothers went to work and came back with three masterworks of their own. There was Gullinbursti, a golden-haired boar that could glow in the dark, run through any substance, and travel faster than horses. There was Draupnir, a golden ring that sprouted eight identical rings every ninth night. Last, but certainly not least was Mjölnir, the crusher. When Loki returned to Asgard, he gave the new hair for Sif and Mjölnir to Thor. The hammer was heavy, and only the thunder god had the strength to wield it. The other prizes Loki divvied up between Odin and Freya.

Found in Södermanland, Sweden, this runestone shows Thor’s hammer, a common theme in Norse inscription, thought to ward off evil and hallow sacral objects.

BerigCC BY-SA 4.0Thor, the Crossdresser

One of Thor’s more embarrassing adventures was precipitated by the theft of Mjölnir. In the Þrymskviða of the Poetic Edda, Thor awakened to find Mjölnir missing:

Wild was Vingthor when he awoke, And when his mighty hammer he missed; He shook his beard, his hair was bristling.[2]

Stumped, Thor went to the other gods and asked for help. They agreed to help Thor in his search, and Loki, borrowing Freya’s falcon cloak, flew away to find the missing hammer. At long last, Loki discovered it in the possession of Thrym, the king of the jötnar and lord of Jötunheimr. In exchange for Mjölnir’s safe return, Thrym demanded Freya’s hand in marriage. This was a proposition that the gods found untenable.

Back in Asgard, Heimdall hatched a scheme—the gods would dress Thor as Freya and Loki as her servant. Once they were disguised, the two gods would gain passage to Jötunheimr where they would reclaim Mjölnir. Proud Thor objected to this plan:

“Me would the gods unmanly call If I let bind the bridal veil.”[3]

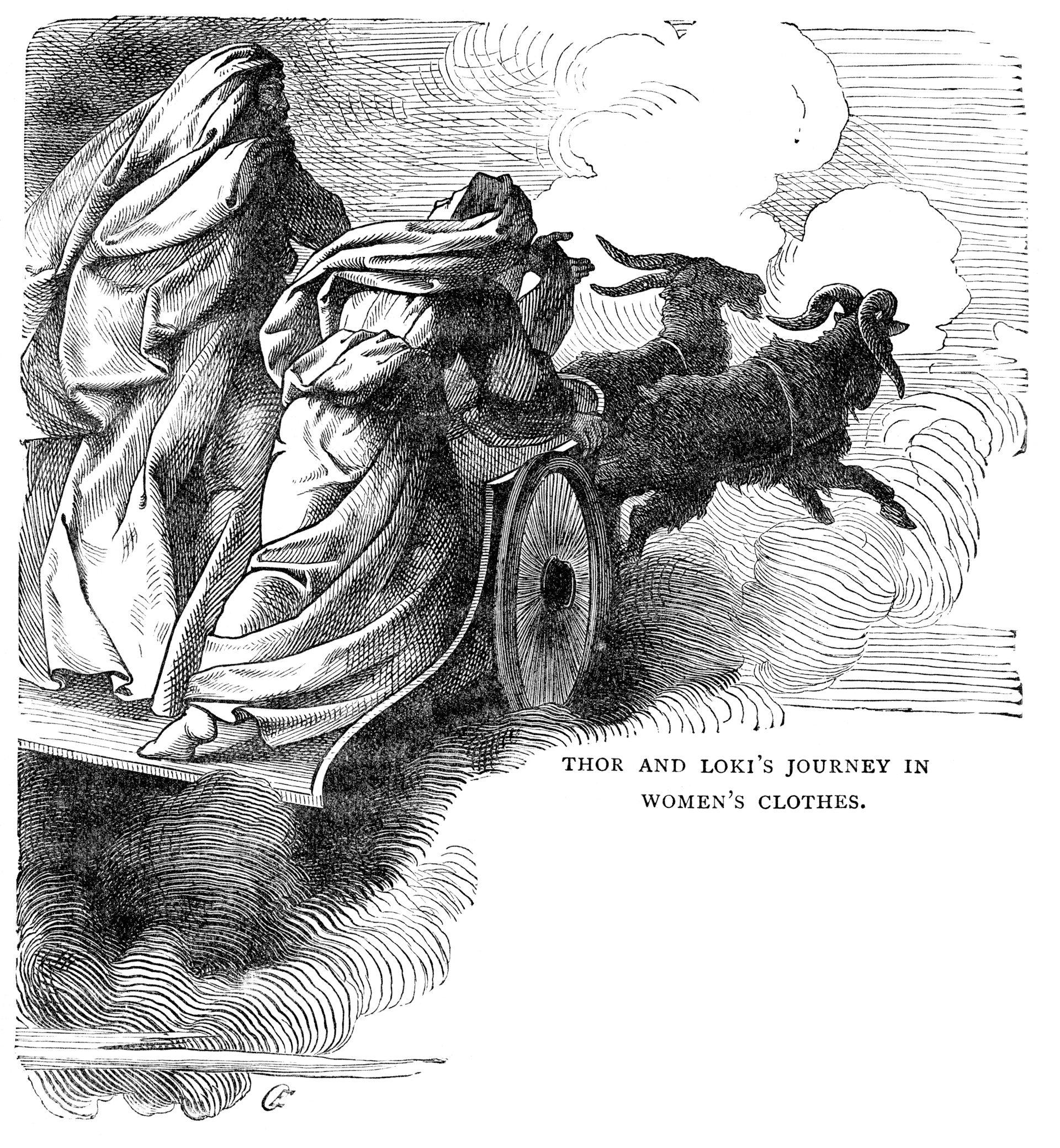

Thor and Loki are disguised in women's clothing in this 1882 illustration.

duncan1890 / iStockLoki, on the other hand, loved the idea and ultimately persuaded Thor to go along with it. The gods clothed Thor in a dress with gems, adorned him with Freya’s prized necklace Brísingamen, and covered his face with a bridal veil. Once all was ready, Thor and Loki traveled to Jötunheimr and gained access to Thrym’s hall. Believing Thor to be his bride, Thrym welcomed him to the hall and feted him with food and drink. Dressed as Freya, Thor devoured an entire ox, eight salmon, and three whole casks of mead. Finding this crude behavior rather odd for the lovely Freya, Thrym exclaimed:

“Who ever saw a bride more keenly bite? I ne’er saw a bride with a broader bite, Nor a maiden who drank more mead than this!”[4]

By this time, drink had made Thrym lusty, and he stole in under the veil for a kiss:

Thrym looked ’neath the veil, for he longed to kiss, But back he leaped the length of the hall: “Why are so fearful the eyes of Freyja? Fire, methinks, from her eyes burns forth.”[5]

Loki, dressed as Freya’s servant, jumped in to quell Thrym’s suspicions. He claimed that Freya had not slept in eight days, so eager was she to reach the king’s hall. Eventually, Thrym’s sister called for the marriage ceremony to commence. Thrym then fetched Mjölnir and placed it on Freya’s lap in order to sanctify the marriage. Laughing, “hard-souled” Thor raised the hammer and murdered the entire wedding party, including Thrym’s old sister:

First Thrym, the king of the giants, he killed, Then all the folk of the giants he felled. the giant’s sister old he slew.[6]

Thor, the Jötunn Hunter

As the grim story in the Thrymskvitha demonstrated, Thor despised the jötnar, and the giants most of all. Thor unleashed this hatred again in the Skáldskaparmál when he tangled with a giant called Hrungnir. The story began when Thor was away in the east slaying trolls—one of his favorite pastimes. Odin met Hrungnir in Jotunheimr and challenged him to a race, the course of which took the rivals and their steeds all the way to the gates of Asgard. Once there, the gods invited Hrungnir in for a drink. He drank his fill and boasted that he would topple Valhalla, raze Asgard to the ground, slay the gods, and carry Freya away to be his wife. The gods soon tired of his taunts:

But when his overbearing insolence became tiresome to the Æsir, they called on the name of Thor. Straightway Thor came into the hall, brandishing his hammer, and he was very wroth, and asked who had advised that these dogs of giants be permitted to drink there.[7]

Thor raised Mjölnir to slay Hrungnir—as he was wont do—but Hrungnir called him a coward for striking an unarmed man. Sensing some truth in the giant’s words, Thor showed mercy and allowed Hrungnir to return to Jotunheimr, where he armed himself with a massive whetstone. In “god-like anger,” Thor followed Hrungnir and cast his hammer at the giant from afar. In response, Hrungnir hurled his whetstone at Thor. The stone struck Mjölnir in mid-flight, however, and shattered into pieces. Though struck, Mjölnir flew on and struck the giant in the head:

But the hammer Mjöllnir struck Hrungnir in the middle of the head, and smashed his skull into small crumbs.[8]

Though Thor smote his opponent, he did not escape the encounter without injury: part of the whetstone lodged itself in his skull. The gods summoned a healer named Gróa, the wife of Aurvandill “the Valiant,” who successfully began to draw the stone from Thor’s head. To encourage her, Thor told her a tale about her husband Aurvandill. Rather than encouraging her, however, the story saddened her, rendering her unable to complete the work. Thus, Hrungnir’s stone, it was claimed, remained in Thor’s skull until Ragnarök.

In the Gylfaginning book of the Prose Edda, Thor again evinced his extreme distaste for giants, this time in the tale of the birth of Sleipnir. Once again, Thor was off in the east hunting trolls when a giant approached the gods and offered to build a palace capable of withstanding any attack by the jötnar. All he asked for in exchange was the sun, the moon, and Freya’s hand in marriage. The gods struck a deal with the giant wherein he would be granted everything he requested so long as he finished the building by the first day of summer. The gods never had any intention of granting the giants’ wishes, however. As the first day of summer neared and the giant’s work grew close to completion, Loki transformed himself into a mare and seduced the giant’s stallion, a magnificently strong beast whose assistance was vital to the giant’s work. Justifiably enraged, the giant attacked the gods, who in typical fashion appealed to Thor for protection. Never one to pass up an opportunity to kill giants, Thor rushed to their aid and smote the builder:

And straightway the hammer Mjöllnir was raised aloft; he paid the wright’s wage, and not with the sun and the moon.[9]

Jörmungandr, the Nemesis

Thor hated many creatures, but none so much as Jörmungandr, the sea serpent of Midgard (one of the Nine Worlds and the home of humans). Jörmungandr was one of the three monstrous offspring of Loki and the giantess Angrboda—the others being the wolf, Fenrir, and Hel, who presided over a kind of underworld—also called Hel—where the souls of the dead gathered. After Jörmungandr’s birth, Odin hurled the monstrosity into the seas surrounding Midgard. The monster eventually grew so large that it completely encircled Midgard and held its own tail in its mouth.

Thor and Jörmungandr tangled multiple times, but the most famous story played out across multiple sources, including the Gylfaginning and a poem called the Hymiskviða in the Poetic Edda. The encounter was part of a long and rambling story about Thor’s search for a cauldron large enough to brew beer for all the gods. Knowing that the giant Hymir possessed such a beastly cauldron, Thor set out to find him.

Thor, with the giant Hymir, is trying to lure and capture Jörmungandr, the sea serpent of Midgard in an 18th century Icelandic Prose Edda manuscript.

Public DomainWhen Thor found the giant, the two went fishing with Thor using the head of Hymir’s best ox as bait (Hymir begrudgingly allowed this). Once at sea, Hymir caught several whales while Thor ensnared none other than the serpent of Midgard, Jörmungandr. Ecstatic, Thor hurled the serpent onto the deck of the ship and smashed him with Mjölnir. Sources disagreed about what happened next, with the Hymiskvida claiming that the monster wriggled free and escaped back into the ocean, and the Gylfaginning claiming that Hymir set Jörmungandr free. Either way, the serpent lived to fight another day. The story concluded with Hymir attacking Thor and Thor slaying him in turn.

The Serpent at Ragnarök

Thor and Jörmungandr were fated to meet again during Ragnarök, the “fate of the gods” and the end of days for the Norse. According to the predictions offered by the völva narrator of the Völuspá (also in the Poetic Edda), the events of Ragnarök would begin when the serpent of Midgard released its tail from its mouth and wriggled onto dry land. There it would join its brother Fenrir, who would set the world aflame while Jörmungandr filled the air with poison. Thor and Jörmungandr would meet one last time, and while Thor was fated finally to kill his foe, he would sustain mortal wounds in the process. Thor would take nine steps after felling the serpent before succumbing to the serpent’s poison and dying:

Nine paces fares the son of Fjorgyn, And, slain by the serpent, fearless he sinks.[10]

Pop Culture

In many ways, Thor’s popularity persisted from the pre-Viking Age to the present era. According to Joseph Grimm, the nineteenth-century folklorist who popularized various Germanic myths and fairy tales, folklore about Thor was common among contemporary Scandinavians, who believed that his lightning frightened off trolls and other creatures of the jötnar.

During the nineteenth century, when Germanic and Scandinavian myth resurfaced to reinforce nationalist agendas, Thor was brought to the forefront of emerging national cultures in Western and Northern European countries. He was commonly depicted in paintings of the period, and writers and poets ranging from Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger (a Dane), to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (an American), to Rudyard Kipling (an Englishman) used Thor as a character in their literature.

Thor’s popularity surged in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries with the emergence of the Marvel comic book franchise and the ensuing Marvel Cinematic Universe. The Marvel works took certain liberties in adapting the thunder god to their fictional worlds. Thor, for example, was always noted to have red hair and a red beard in Norse mythology. In the comics, Thor was portrayed with blonde hair and beard, and this look was maintained for the film adaptations of the character. Additionally, while Loki was portrayed as Thor’s adopted brother in Marvel products, their relationship was less certain in myth. Loki was often portrayed as Thor’s uncle in traditionally Norse mythology, though there were times where his role was more ambiguous.

In many ways, however, the Marvel comics and movies remained true to the mythic Thor—he was brave, powerful, and violent. So too, he was filled with fondness for his hammer and enamored with beer. In other words, Thor maintained his status as the perfect Norse hero.