Styx

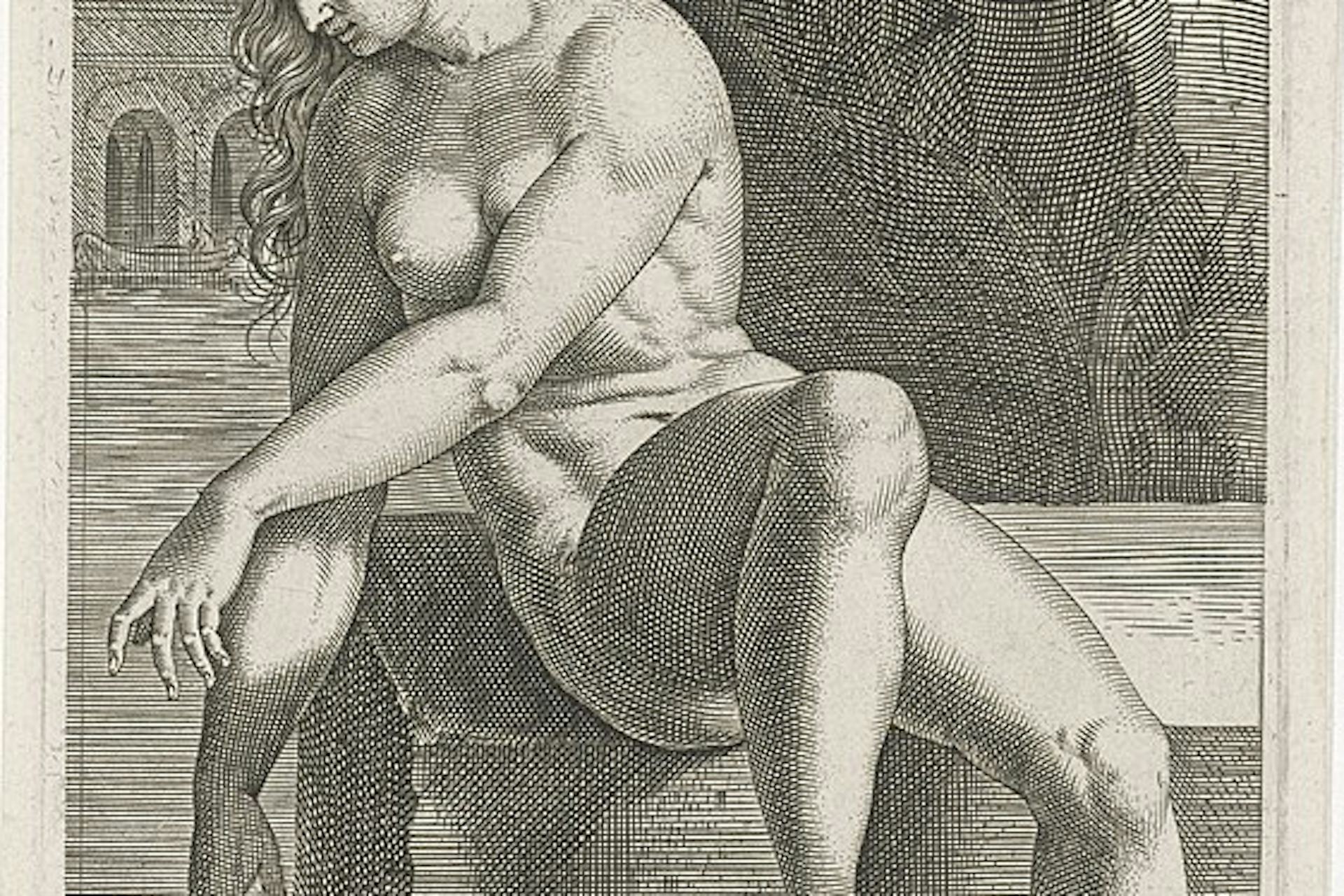

Styx by Philips Galle (1587)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainOverview

Terrible Styx, eldest daughter of Oceanus and Tethys, was one of the rivers of the Underworld and its goddess. The goddess Styx had supported the Olympians during their war against the Titans, and as a reward gods swore their most powerful oaths by her waters. Styx herself married her Titan cousin Pallas. Their children were Zelos (“Rivalry”), Nike (“Victory”), Kratos (“Strength”), and Bia (“Force”).

Etymology

The name “Styx” (Greek Στύξ, translit. Stýx) is an archaic formulation of the verb στυγέω (stygéō), meaning “hate, abhor, hold back.” Styx’ name appropriately means something like “Abhorrence.” Etymologically, the word may have originated in an Indo-European root *steug-.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Styx Στύξ (translit. Stýx) Phonetic

IPA

[stiks] /stɪks/

Titles and Epithets

As a daughter of Oceanus and Tethys, Styx was an “Oceanid” (Ὠκεανίς, Ōkeanís). The other epithets we find for Styx in Greek literature could describe her both as a goddess and as a river. As a goddess, Styx was sometimes called δεινή (deinḗ), a word that means “terrible” but also “formidable” and “awesome.”[2] As a river, on the other hand, the waters of the Styx were called κατειβόμενον (kateibómenon, “down-flowing”)[3] or simply ψυχρόν (psychrón, “cold”).[4]

Attributes

General

As a goddess, Styx can be imagined like most other goddesses: beautiful, dignified, regal. According to Hesiod,

She lives apart from the gods in her glorious house vaulted over with great rocks and propped up to heaven all round with silver pillars.[5]

But Styx was also a place—one of the rivers of the Underworld, over which the goddess Styx ruled. This dreaded river was usually described as a branch of the Ocean, the vast, world-encircling river embodied by Styx’s father Oceanus. Hesiod evocatively describes the river Styx as

the famous cold water which trickles down from a high and beetling rock. Far under the wide-pathed earth a branch of Oceanus flows through the dark night out of the holy stream, and a tenth part of his water is allotted to her. With nine silver-swirling streams he winds about the earth and the sea's wide back, and then falls into the main; but the tenth flows out from a rock…[6]

Of course, notions of the Styx mutated over time. Plato even envisaged it as a lake rather than a river.[7]

As one of the rivers of the Underworld, the Styx acted as a boundary between the world of the living and the world of the dead. The Styx encircled the Underworld nine times.[8] The other important rivers surrounding the Underworld were the Acheron, the Cocytus, the Phlegethon or Pyriphlegethon, and the stream of Lethe. Some added that the Cocytus was actually a branch of the Styx, just as the Styx was a branch of the Ocean.[9]

Roman authors sometimes represented Charon ferrying the souls of the dead across the Styx, though earlier sources had usually associated Charon with the Acheron.[10]

Many ancient authorities placed the Styx in the central Greek region of Arcadia, near the town of Nonacris. There was indeed a river there called the Styx (today it is called Mavronéri—“Black Water”—and is still identified with the Styx). The waters of this real-life river, fed by snow from the mountains, were icy cold—so cold, it was said, that they were instantly fatal. Locals made oaths by this river and transported its freezing water in vessels made from the hooves or horns of animals (any other materials were supposedly corroded by the water).[11] According to one legend, Alexander the Great was poisoned with water from this river.[12] Others, however, seem to have placed the Styx further north, closer to the River Titaressus in northern Greece.[13]

Mavroneri, a river in the Aroania Mountains in Achaia, Greece, near the city of Nonacris, identified since antiquity with the mythical River Styx

Artemis KatsadouraCC BY-SA 4.0Conversely, the Styx was also sometimes seen as a kind of elixir of life or immortality. This belief seems to have originated in later times. Take, for example, the myth in which Thetis tried to make her son Achilles immortal by dipping him into the waters of the Styx.[14]

But perhaps the most important attribute of the river Styx was its role in the oaths of the gods. When the Olympians first assumed control of the cosmos, Zeus decreed that an oath by the Styx was unbreakable. It is because of this that the Greek myths are full of gods making oaths by the Styx.

Iconography

Styx rarely appeared in ancient art. Only a few representations of her are known, and most of them show her in connection with the mythical scene in which Thetis tries to make her son Achilles immortal by dipping him into the Styx.[15]

Family

In the most familiar tradition, Styx was the firstborn daughter of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys, early gods of the sea. She was thus one of the three thousand Oceanids; her brothers were the three thousand Potamoi or “Rivers.”[16] But another tradition, reported in Hyginus’ Fabulae, claimed that Styx was the daughter of Nyx and Erebus, primordial deities who represented night and darkness.[17]

Detail from a mosaic depicting Oceanus and Tethys (third century CE)

Zeugma Mosaic Museum, Gaziantep / Bernard GagnonCC BY-SA 3.0Styx was married to Pallas, the son of the Titan Crius. Their children, according to Hesiod, were the personifications Zelos (“Rivalry”), Nike (“Victory”), Kratos (“Strength”), and Bia (“Force”);[18] Hyginus adds that they were also the parents of the Fountains, Lakes, and of the monster Scylla.[19]

According to Epimenides of Crete, a semi-legendary author of the seventh or sixth century BCE, Styx had a different consort, an otherwise unknown figure named Peiras, by whom she was the mother of the monster Echidna.[20]

Yet another obscure tradition, reported by the mythographer Apollodorus, made Styx one of Zeus’ many lovers and named her as the mother of Persephone, the bride of Hades and queen of the Underworld.[21]

Mythology

Origins

Styx originated from a branch of the Titans who were friends to the Olympians. Her parents, Oceanus and Tethys, were both Titans themselves, but they chose to support Zeus and the Olympians rather than their Titan siblings during the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympians and Titans. Styx likewise was an ally of the Olympians. Because of this, Styx, her parents, and her many siblings continued to thrive after the Olympians became the rulers of the cosmos, while the other Titans were imprisoned forever in Tartarus.

Styx Between the Titans and the Olympians

When Zeus and his siblings waged their war against the Titans, led by the savage Cronus, they sought all the help they could get. Styx, sent by her father Oceanus, went with her fearsome children Zelos (“Rivalry”), Nike (“Victory”), Kratos (“Strength”), and Bia (“Force”) to join Zeus: she was his first ally.[22]

After ten years, Zeus and his siblings finally triumphed over the Titans. Cronus and the other defeated Titans were locked up in Tartarus. Zeus and his siblings went to live on Mount Olympus, from which they came to be known as the “Olympians,” and became the new rulers of the universe.

The Olympians lavished honors on all who had helped them defeat the Titans. Styx’s honors were especially noteworthy. Styx’s children, Zelos, Nike, Kratos, and Bia, lived with Zeus himself on Mount Olympus.[23] Styx herself was appointed to be the “great oath of the gods:”[24] any oath that was sworn by her waters could not be broken.

Styx and the Oaths of the Gods

Whenever one of the gods needed to swear a solemn oath, they would swear it by the waters of the Styx. Iris, one of the messengers of the gods, would be sent to the Underworld to collect some water from the Styx in a golden jug. The god would then make their oath while pouring out a libation from the jug.[25] Other sources do not generally describe this ceremony when a god swears by the Styx, suggesting that just naming the river was enough.

Iris Carrying to Water of the River Styx to Olympus for the Gods to Swear By by Guy Head (1793)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MOPublic DomainAn oath sworn by the Styx was unbreakable. If the oath was broken, a terrible penalty was exacted:

For whoever of the deathless gods that hold the peaks of snowy Olympus pours a libation of her water and is forsworn, must lie breathless until a full year is completed, and never come near to taste ambrosia and nectar, but lie spiritless and voiceless on a strewn bed: and a heavy trance overshadows him. But when he has spent a long year in his sickness, another penance more hard follows after the first. For nine years he is cut off from the eternal gods and never joins their councils or their feasts, nine full years. But in the tenth year he comes again to join the assemblies of the deathless gods who live in the house of Olympus.[26]

The deterrent power of these penalties was evidently quite effective: for we hear of no gods who actually broke an oath sworn by the Styx, though we hear of many gods making such oaths.

Pop Culture

The River Styx continues to feature in modern adaptations of Greek mythology: today it is perhaps the most familiar river of the Greek Underworld. The Styx makes appearances, for example, in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series as well as in his Trials of Apollo series. In cinema, the Styx has also been represented in the TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess, where its waters appear typically eerie: dark, murky, covered in the requisite layer of misty fog. In Disney’s animated Hercules (1997), the Styx is a nauseous green river in which the souls of the dead are imprisoned for eternity.

Styx and her river also have numerous modern namesakes, including the rock band Styx and one of Pluto’s moons.