Skanda Karttikeya

Overview

Karttikeya—son of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction, and his wife Parvati—plays an important role in the Hindu pantheon as the leader of the gods’ army. While not as well known as his brother, the elephant-headed god Ganesha, Karttikeya is popular throughout South Asia, especially in the Tamil-speaking south, where he is known as Murugan.

Karttikeya’s various origin stories offer different accounts of his parentage, but most sources agree that both Agni and Shiva played important roles in his conception and birth. Much like Krishna, Karttikeya is often depicted as a young man or infant due to his epithets, “Kumara” and “Murugan,” meaning “boy” or “youth.”

Karttikeya made a name for himself as the slayer of the demon Taraka, who had oppressed the gods for centuries. In some versions of his birth, his very conception was the result of the gods’ search for someone powerful enough to defeat the demon.

Etymology

Karttikeya derives his name from the Krittikas, the six goddesses who personify the Pleiades constellation and who nursed him as an infant. “Karttikeya” can thus be translated as “of the Krittikas” or “relating to the Krittikas.”

His other common name, Skanda, means “shedding, hopping, leaping” or “effusion” in Sanskrit.[1] He came by this name because the seed of his father, whether Shiva or Agni, was too powerful to bear, and so it was cast off or “shed” (Sanskrit skanna). It was from this cast-off seed that Skanda was born.

This etymology appears numerous times in the relevant Sanskrit literature, including the Ramayana: “Because the seed (skannaṃ) flowed from the womb, the gods called him ‘Skanda.’”[2]

Pronunciation

English

Sanskrit

Karttikeya or Kārttikeya कार्त्तिकेय Phonetic

IPA

[Kahrt-ti-KAY-uh] /ka:rttɪke:jɐ/

Titles and Epithets

Kumāra (कुमार), “Young”

Murugan (मुरुगन्), “Youth”

Shanmukha (शन्मुख), “Six Heads”

Skanda (स्कन्द), “Shed”

Subrahmaṇya (सुब्रह्मण्य), “Dear to Brahmins”

Tārakavadha (तारकवध), “Taraka-Slayer”

Sanankumāra (सनंकुमार), “Ever Young”

Attributes

Much like the popular god Krishna, Karttikeya is often portrayed as a child or youthful figure due to his nickname Kumara, meaning “youth” or “boy.” His mount is a peacock named Paravani that he defeated in battle and pressed into service. Karttikeya has a distinctive appearance due to his six heads, which he grew so that the six Krittikas could all nurse him at the same time. He can also be identified by his red or golden skin and is typically shown wielding a spear.

Domains

Karttikeya is a fearsome god of war as well as of beauty and youth.

Family

Karttikeya’s parentage is a complicated matter, as Shiva, Agni, and several other gods and goddesses all played important roles in his birth. The most common myth holds that his father and mother are Shiva and Parvati, making the elephant-headed god Ganesha his brother. His consorts are Devasena (literally “Army of the Gods,” stressing his martial qualities) and Valli.

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

As with many Indic figures, Karttikeya’s origins are uncertain; he does not appear in Vedic literature and is likely the result of disparate gods merging over centuries. A. L. Basham claims that Skanda or Kumara (other names for Karttikeya) “was probably originally a non-Āryan divinity” whose cult became widespread in the early centuries CE before waning in the medieval period.

In the south of India, his cult remained popular, and “the name and attributes of the god were imposed on the chief deity of the ancient Tamils, Murugan, by which name Skanda is still sometimes known in the Tamil country.”[3] Basham explains that Murugan was originally an orgiastic fertility and mountain god with similar characteristics to the hypermasculine mountain god Shiva.

Richard Mann stresses the importance of non-Indic elements and populations in Skanda’s development. Based on iconographic and early textual evidence from the Mahabharata and Ayurvedic texts, he argues that “Skanda was a central part of a propitiation cult designed to protect children from disease-causing deities in and around the Mathurā region.”[4]

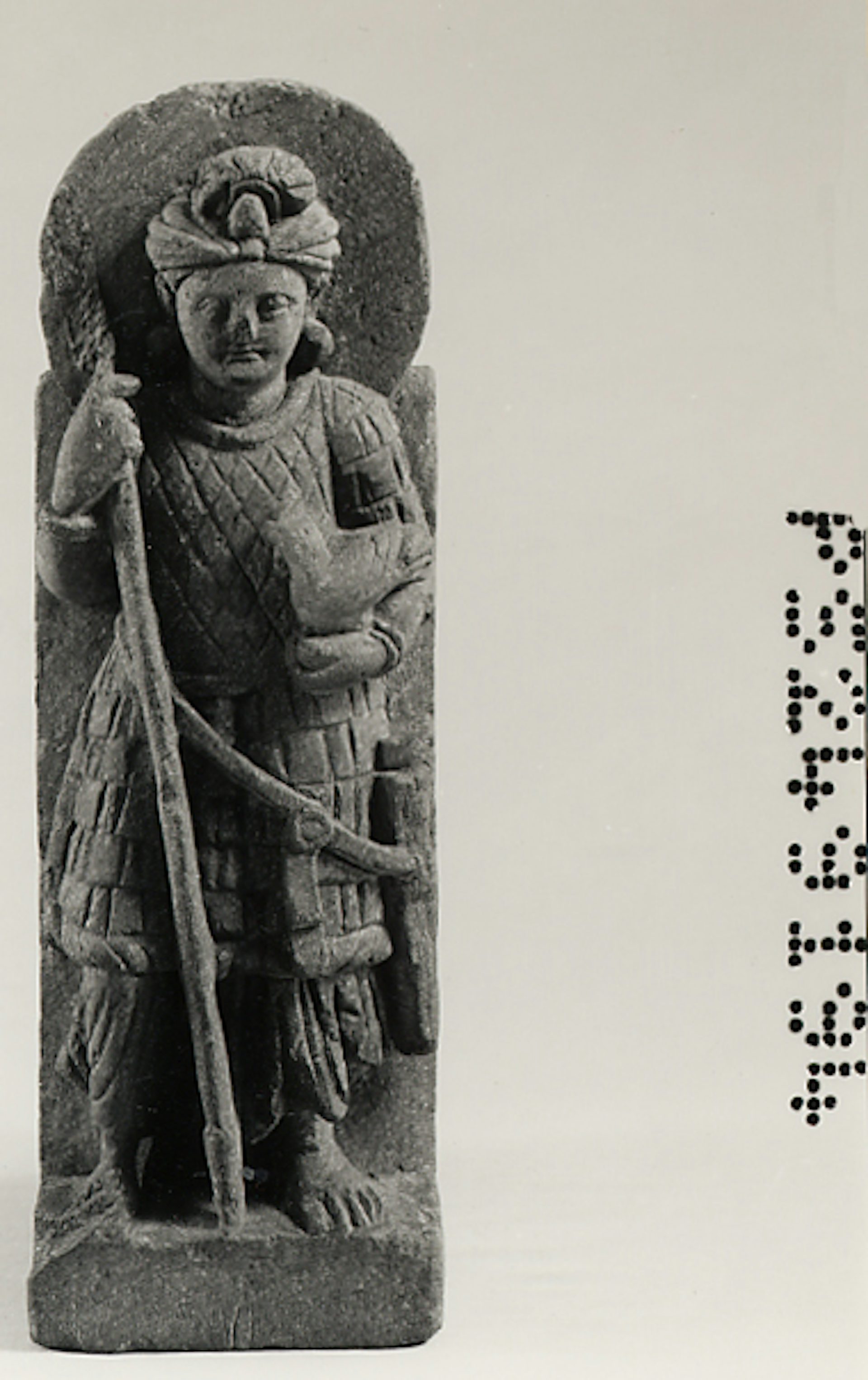

According to Mann, it was the rising power of the incoming Parthians, Indo-Scythians, Indo-Greeks, and Kushanas in the early centuries CE that spurred Skanda’s evolution into the god of war. Indeed, in iconography, Skanda is routinely depicted as wearing more militaristic Parthian-style or Kushana-style clothing. By the Gupta period, Skanda had achieved the form recognizable to modern Hindus as Karttikeya.

Schist sculpture of Skanda-Karttikeya dressed as a Kushana noble. A halo, indicative of the Gandharan school, frames his head. His right arm holds a spear while his left holds a bird, possibly a chicken or peacock. Gandhara, ca. second century CE.

Trustees of the British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Taking all the different tales of Karttikeya’s birth into consideration (see below), Pranabananda Jash summarizes Karttikeya’s tangled development as follows: “Whatever might have been the earlier history of the origin of Skanda Karttikeya, it is undoubtedly a product of a complex intermeshing of numerous ethnic and cultural elements in its final stage.”[5]

Birth and Parentage

Karttikeya’s mythology—like that of his brother, the elephant-headed god Ganesha—largely focuses on his birth. The main disagreement among the various surviving textual traditions is whether his father is Agni, the god of fire, or Shiva, the god of destruction.

Birth by Agni and Svaha in the Mahabharata

According to the version told in the great Hindu epic the Mahabharata, Skanda-Karttikeya is the son of Agni, the fire god, while Shiva and Parvati play no role whatsoever in his birth.

The story begins long ago, when the terrible demon Taraka was oppressing the gods and overwhelming them in battle. Indra went looking for a virile hero who could lead his heavenly army and defeat Taraka once and for all. Soon he came upon the maiden Devasena (literally “Army of the Gods”), who told him that her future husband would be a mighty warrior and conqueror of all the gods’ enemies. This power would be due to a blessing granted by her father, but only the successful suitor would receive that blessing.

All the gods assembled at the hermitage of Vasishtha and six other powerful sages, where they arranged for a great fire sacrifice. After Agni, the god of fire, had taken the oblations to heaven and returned, he gazed upon the wives of the seven sages and lusted madly for them. His desire—or more specifically, his anguish at being unable to act on his desire—drove him to such despair that he resolved to go into the forest and abandon his body (that is, commit suicide).

At this time, the goddess Svaha desired Agni and resolved to seduce him through trickery. After transforming herself to look like one of the sages’ wives, she made love to him. But because Agni’s seed burned, she transformed herself into a bird and dropped it into a golden pot far away on a mountain plateau. Six times she took on the form of one of the wives, and each time she left the seed in the pot on the mountain.

Within no time at all—a mere four days—the seed formed itself into the god Skanda-Karttikeya, with six heads and twelve arms and legs. Glowing like the rising sun, he bellowed a great roar that shook the gods, demons, and even the earth itself to the core.

Indra, the king of the gods, saw Skanda’s great power and was afraid, fearing that one day Skanda would overthrow him. Thus, he sent the six Krittikas, the stars of the Pleiades, to slay the child.[6] But their hearts melted upon seeing the young Skanda, their breasts overflowed with milk, and they resolved to treat him as their son. For this reason, he is known as Karttikeya, “Son of the Krittikas.”

But Indra was not so easily foiled in his efforts: he assembled his army and attacked Karttikeya while the boy was still young. The youthful god roared once more upon seeing the army of the gods, and a great bellow of flame erupted from his mouth, burning many. Seeing this, Indra gave up his efforts and the two made peace, with Skanda-Karttikeya being appointed general of the gods’ army.

In recognition of Skanda’s might, Indra arranged for him to marry Devasena, and the powerful blessing given to her by her father passed on to Skanda. Because of this marriage, Skanda-Karttikeya is also known as Devasenapati, meaning “Lord of Devasena,” or, more literally, “Lord of the Army of the Gods,” a reference to both his marriage and his position as general.

Birth by Shiva (and then by Agni and Ganga) in the Ramayana

The Ramayana relates two different tales of Karttikeya’s birth. In this epic poem, Rama and his brother Lakshmana ask the sage Vishvamitra to tell them what he knows about the goddesses Uma (also known as Parvati) and Ganga, two daughters of the mountain god Himalaya.

In the first tale, Vishvamitra recalls that, after their marriage, Shiva and Parvati spent over a hundred years consummating their love. Fearing that a child too powerful to control would come of their union, the gods asked the creator god Brahma what they should do. Together, they all went to Shiva and begged him not to have a child. Out of kindness and regard for the welfare of the world, Shiva agreed. “But,” Shiva asked, “who should receive my seed if I should shed it?” And the gods answered that the earth should receive it.

The poem continues:

Thus answered, Shiva shed his seed on the surface of the earth,

And the earth with her mountain groves was covered with its splendor.

Then the gods said this to the oblation-eater (the fire god Agni),[7]

“Enter that great splendor of Shiva, together with the gods of winds and airs.”

And there arose a white mountain covered with that fire,

and a heavenly forest of reeds as bright as the sun,

wherein illustrious Karttikeya was born of fire.[8]

When Parvati discovered what had happened, she was furious at the gods for having begged Shiva not to conceive a child with her, and at the earth goddess for having received his seed. In her rage, she cursed the gods to be forever childless.

This version is noteworthy due to the total absence of the demon Taraka. In this account, Karttikeya’s birth is not planned as a means of defeating the demon but is instead accidental, the result of Shiva letting his seed fall to the earth.

The second tale concerns Parvati’s sister Ganga, the divine embodiment of the great Ganges River in north India. Immediately after being cursed by Parvati, the gods went to Brahma and asked him what they should do now. The curse was permanent, Brahma said, and the gods would never be able to bear children again—except for Agni and the goddess Ganga, who would bear a child so powerful that he would destroy the enemies of the gods.

Not wanting to waste any time, Agni propositioned Ganga for a child, and she agreed. The goddess made love in the form of a heavenly nymph. Soon, her very veins were aflame with the child she was bearing, and her whole body felt as if it was on fire. She was forced to take the golden fetus out of her divine womb and place it carefully high up in the mountains.

All around the golden fetus the earth turned to silver, and beyond that copper and other precious metals. Soon the six Krittikas came to nurse the child, who grew six heads so that he could drink from all of them at once. He quickly grew powerful enough to challenge the gods’ enemies, and so the gods made him the general of their armies.

Birth by Shiva in the Vamana Purana

As if aware of the many competing versions of Karttikeya’s birth, the one found in the Vamana Purana offers a creative solution that allows for many different gods to be considered his parents.

After interrupting the love-play of Shiva and Parvati, Agni consumed Shiva’s seed so that the powerful substance would not fall to the earth and destroy the cosmos. But even he, the god of fire, was burned with searing heat. He carried it for five thousand years—so long that his entire body became golden, thus giving him the nickname Hiranyaretas, “Golden Seed.”

But at last he could endure the burning no longer, and he sought the river goddess Kutika. Explaining that the seed would cause untold destruction unless someone bore it, Agni persuaded Kutika to take it within her flowing waters.

After bearing the seed for another five thousand years, Kutila, too, was unable to take the terrible heat. And so she went to the creator god Brahma for counsel, who told her to throw the seed into a vast thicket of reeds high up in the mountains. After ten thousand years, he said, it would finally develop into a child.

In time, the vast thicket and all the wildlife nearby turned a brilliant golden color, and when the child Karttikeya was born at last, the six Krittikas came by and nursed him. Just as with the other versions, the boy grew six heads so that all six could nurse him at once.[9]

At the time, only Brahma knew of Karttikeya’s birth, but when Agni learned that the child had been born, the fire god raced as quickly as he could to the thicket, with the goddess Kutila beside him. Shiva and Parvati accompanied them as well.

Agni, Kutila, Shiva, and Parvati were each convinced that they were the rightful parents of the child. The wise Parvati suggested that the child should decide: he would be the son of whomever he went to for protection. Everyone agreed to this, but Karttikeya would not leave anyone out. Just as he had grown six heads to satisfy all the Krittikas, he now split himself into four different figures, with each going to a different parent.

Karttikeya went to Agni in the form of Mahasena, to Shiva as Kumara, to Parvati as Vishakha, and to Kutila as Shakha. When the Krittikas asked who the father of the child was, Shiva responded:

By the name of Karttikeya he will be your little boy; as Kumara he will be the immortal son of Kutila; as [Parvati’s] son he will be called Skanda, and as Guha he will be mine. As [Agni’s] little boy, he will be known as Mahasena, and as the son of the reed thicket, Sharadvata. Because of his six faces, the long-armed one will be called Shanmukha, or Six-Face. So will the lord, the great Yogin, be known on the earth.[10]

In this way, the Vamana Purana is able to explain why many gods and goddesses claim Karttikeya as their own, as well as the origin of the various names he is known by.

The Slaying of Taraka

In many accounts, Karttikeya is best known for slaying the demon Taraka. As the story goes, long ago the asuras and devas (titans and gods) waged an endless war for supremacy. During this time, the demon Taraka undertook many years of yogic asceticism in order to appease the creator god Brahma and receive a blessing. His asceticism grew so fierce that he generated immense heat and burned the world.

In exchange for ending this fiery destruction, Taraka demanded that Brahma bless him with a form of invincibility: according to this blessing, no god, not even Shiva or Vishnu, could harm him, and only a child born of Shiva could slay him. With this newfound invulnerability, the titan oppressed the gods and drove them away in battle after battle.[11]

The gods, meanwhile, did all they could to ensure that Shiva enjoyed his marriage bed with Parvati so that they would have a child. In time, Karttikeya was born, and he quickly grew to be a mighty and competent warrior. For besting Indra in battle, he was appointed general over all the armies of the gods and received Indra’s daughter Devasena, “Army of the Gods,” for a wife.

When the titan Taraka heard of this child, he rushed to assemble an army. Karttikeya, though still an infant, mounted his war elephant before ultimately deciding on a fantastical flying chariot for his vehicle in the upcoming battle. Soon the two armies were arrayed against each other with elephants, chariots, foot soldiers, and horsemen, and the roars of their battle cries echoed like thunder clouds before the rainy season.

Hundreds of thousands fell in the ensuing battle. Severed elephant trunks and heads littered the ground. Gods and asuras clashed. Many warriors on the gods’ side challenged Taraka, among them Muchukanda and Virabhadra, and only the boon granting Taraka near-invincibility saved him from death. Though Muchukanda pierced him with a javelin and Virabhadra shot him with a trident, he got up instantly each time.

The gods put the army of the asuras to rout, and in revenge Taraka sprouted a thousand arms, mounted a lion, and sprang upon the gods’ army. His lion ravaged their mounts—horses, elephants, and bulls. And with his thousands of weapons, he slashed limbs and severed divine heads. He even laid low Indra, the king of the gods, striking him with his own lightning bolt.

At last, Taraka and Karttikeya faced each other, and the titan mocked Karttikeya and all the gods for pitting an infant boy against him in battle. Javelins flew back and forth between them. Each struck the other. Though the odds seemed insurmountable, a disembodied voice spoke above the battlefield to console the gods and their army and reassure them that the boy was certain of victory. After honoring Shiva, Parvati, and Vishnu, Karttikeya at last cut off the demon’s head with one swift stroke.

The victors rejoiced at winning the day, and Indra and all the rest showered the boy with flowers.

The Race Around The World

For all of Karttikeya’s might and skill in war, his elephant-headed brother Ganesha is a wily god who sometimes outwits his stronger brother. According to the Shiva Purana, both Ganesha and Karttikeya desired to be the first of the brothers to marry, and their parents, Shiva and Parvati, decided to settle the matter with a contest: whoever could travel around the world fastest would have the honor.

With that, the race was on, and Karttikeya immediately sped away across the world, fast as lightning. As the stronger and faster of the two, he was confident that he would soon be married. Meanwhile, the wily Ganesha stayed at home and walked around Shiva and Parvati. He then announced that he had won the race and expected his marriage to begin soon.

According to Ganesha, his parents were his world, and so in walking around them he had circled the globe. They relented with great pride and admiration, and he was married shortly thereafter.[12] Meanwhile, Karttikeya was greatly distressed at having lost the race so underhandedly, causing a lasting rift between him and the rest of the family.

Karttikeya in Buddhism

As is often the case with gods in Hindu mythology, Karttikeya also appears in Buddhism, where he is known in the early Pali texts as Sanankumara, “Ever Young.” Although not as important in Buddhism as Indra or Brahma, Karttikeya remains a powerful god who protects the Buddha. He is classified as a Mahabrahma, a great Brahma, one of the mightiest categories of gods.

Sanankumara also takes an active role in preaching to the other gods about the benefits of following the Buddha. According to the Janavasabha Sutta, the thirty-three gods that made up much of the Vedic pantheon had assembled to discuss important matters. Sanankumara disguised himself and descended from his own heaven to converse with them. Manifesting thirty-three exact doubles of himself, he spoke with each of the gods at once about the virtues of the Buddha and his followers, changing his persuasion tactics and words to suit each particular god’s disposition.

Sanankumara is often cited as the author of the following Buddhist verse:

The Kṣatriya is best among those beings who favor the clan.

One accomplished in wisdom and conduct is best among gods and men.[13]

As the god traveled to East Asia along with the rest of the religion, he developed into a Dharmapala, a guardian deity who protects Buddhas and their teachings. In China he is worshipped as 鳩摩羅天 (Jiū mó luó tiān).

Worship

Festivals and/or Holidays

Thaipusam, a three-day ceremony honoring the moment when Murugan-Karttikeya received his spear from his mother Parvati, is popular throughout Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Southeast Asia.

Temples

Karttikeya has active and thriving temples across South and Southeast Asia. The Batu Caves near Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia are notable for boasting the largest statue of Murugan in the world, painted in gold and standing 140 feet tall.

Pop Culture

Karttikeya remains a popular Hindu god to this day. In Tamil Nadu and other areas with a strong Tamil presence, such as Sri Lanka and Malaysia, he is widely worshipped as Murugan and is one of the most important gods in the region.