Shield of Heracles

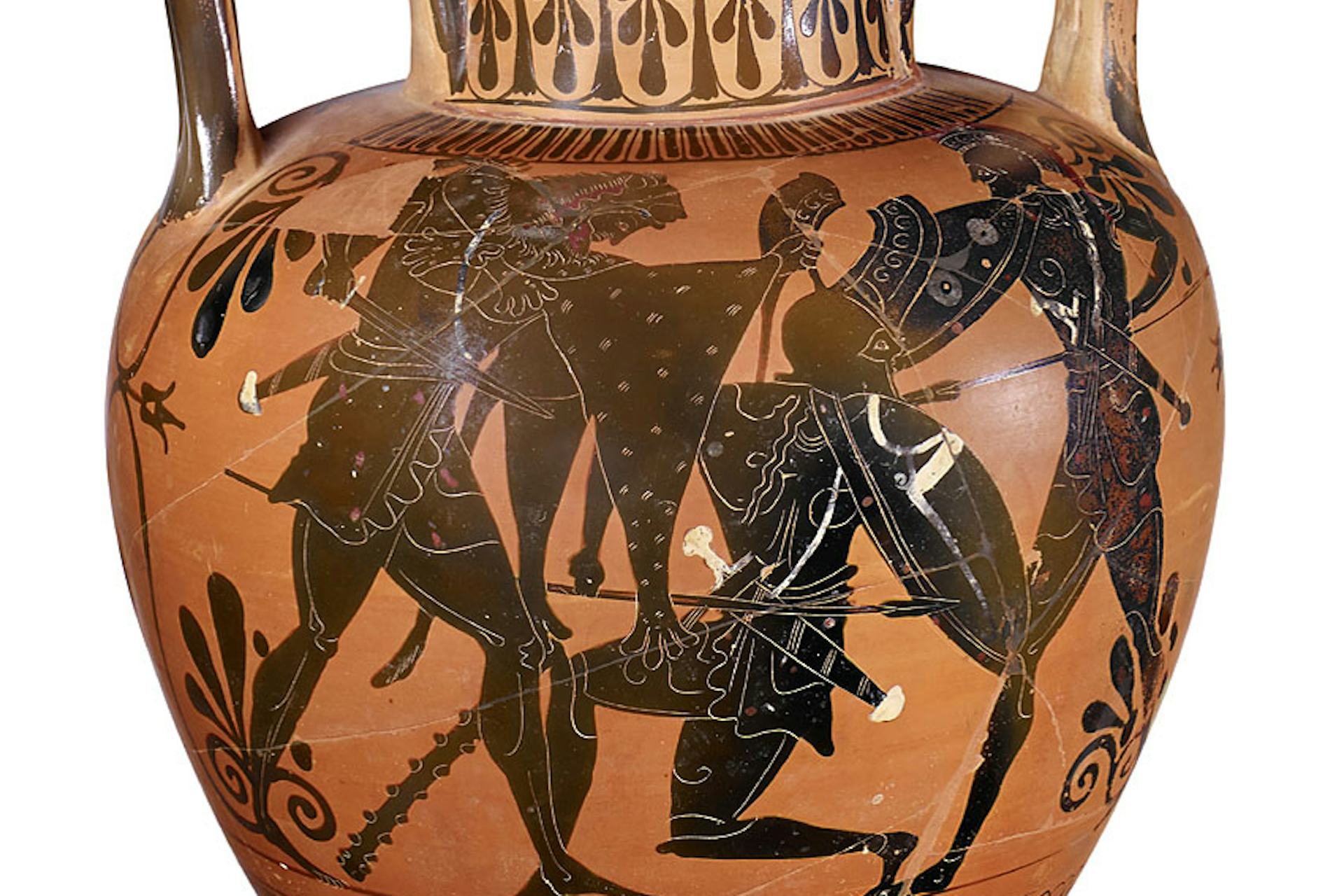

Attic black-figure neck amphora depicting Heracles (left) and Iolaus (right) fighting Cycnus (center), attributed to the Painter of Oxford 569 or to the Leagros Group (ca. 510–500 BCE)

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe HamburgCC BY 3.0Overview

The Shield of Heracles, sometimes known simply as the Shield, is a short Greek epic poem. It was traditionally listed as one of the works of Hesiod (best known as the author of the Theogony and the Works and Days). However, most scholars today claim that the Shield of Heracles was actually written by a later poet. It was probably composed around the early sixth century BCE, roughly a century after Hesiod produced his other famous epics.

Further complicating matters is the fact that the beginning of the Shield of Heracles appears to have been recycled from the Catalogue of Women, another epic poem traditionally attributed to Hesiod. Consequently, the Shield of Heracles likely represents not a single poem with a single author but rather a hodgepodge of multiple poems or fragments by many different authors.

The Shield of Heracles tells of a battle between Heracles, the greatest of the Greek heroes; Cycnus, a formidable warrior in his own right; and Cycnus’ father Ares, the god of war himself. This battle, which is only briefly recounted, ends with Heracles killing Cycnus and injuring Ares. But the heart of the poem is a long and detailed description—known as ekphrasis in Greek—of the ornate shield Heracles carries with him into battle. This is a remarkable passage with important parallels in other ancient epics.

Title

The poem’s full title, Shield of Heracles (Greek Ἀσπὶς Ἡρακλέους, translit. Aspìs Hērakléous), is frequently shortened to just Shield (Greek Ἀσπίς, translit. Aspís). Some scholars refer to the poem by its Latin name, Scutum (the Latin word for “shield”).

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Shield of Heracles Ἀσπὶς Ἡρακλέους (translit. Aspìs Hērakléous) Phonetic

IPA

[sheeld uhv HER-uh-kleez] /ʃild əv ˈhɛr əˌkliz/

Author

In antiquity, the Shield of Heracles was traditionally attributed to Hesiod, the author of the Theogony and the Works and Days. He is one of the earliest known Greek poets, writing around 700 BCE.

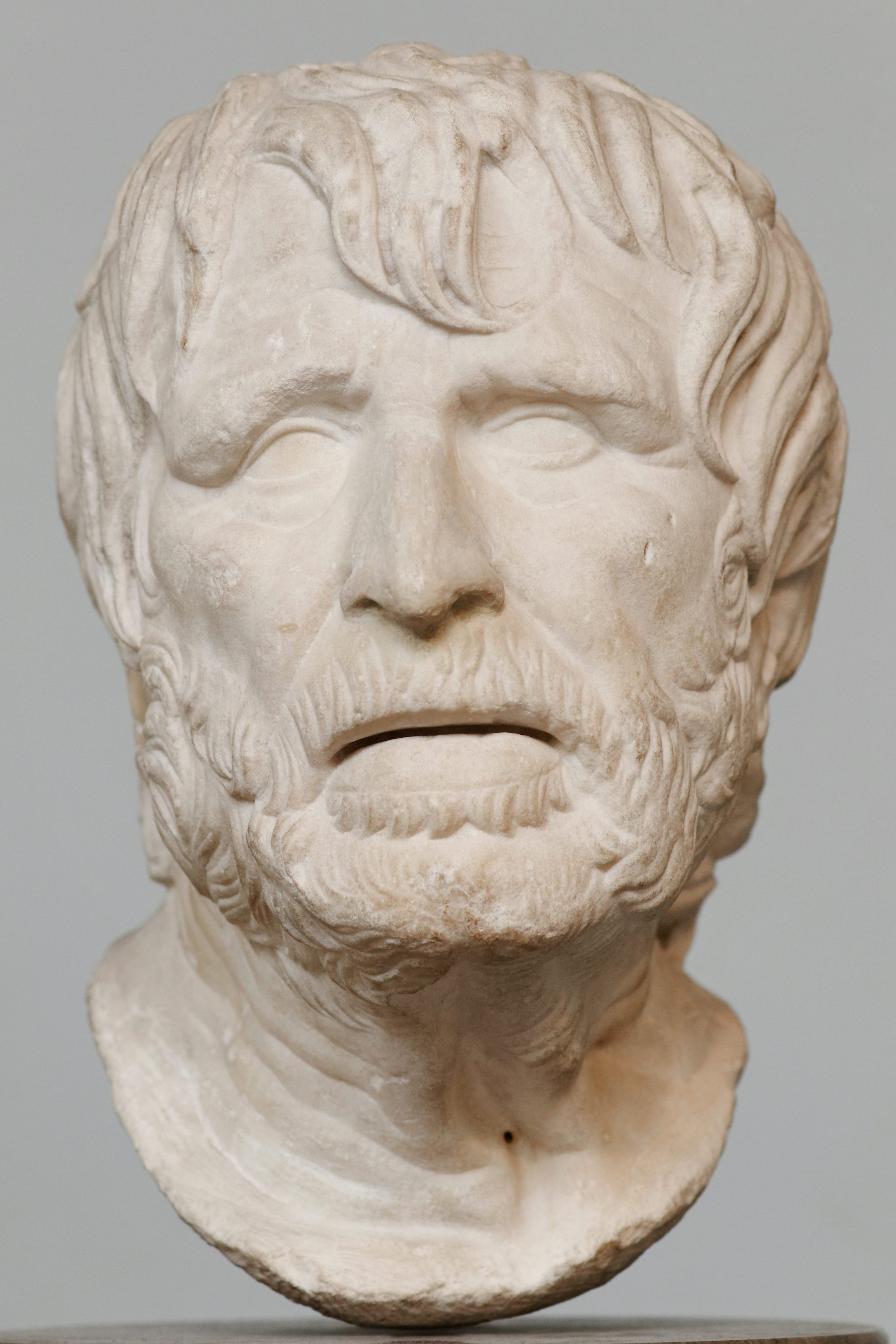

The so-called “Pseudo-Seneca,” now thought to be an imaginative portrait bust of Hesiod. Roman copy of Greek original from around the 2nd century BCE.

British Museum, London / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainHowever, the authorship of this text has long been contested. The ancient scholar Aristophanes of Byzantium noted that the opening lines of the Shield of Heracles were taken from the Catalogue of Women, another epic attributed to Hesiod—but the authorship of the Catalogue is equally unclear.

Today, scholars usually date the Shield of Heracles—or at least the parts of it not taken from the Catalogue of Women—to the first decades of the sixth century BCE. Since Hesiod was writing over a century earlier, this means that he could not possibly be the poem’s author. Unfortunately, nothing at all is known about the true author of the Shield of Heracles.

Mythological Context

The Shield of Heracles represents an interesting stage in the development of Heracles’ myth. Often remembered as the most famous of the Greek heroes, Heracles carried out an extraordinary number of heroic exploits—more than enough to fill several lifetimes, as ancient authors sometimes pointed out.

But the myth of Heracles took time to develop. In the earliest works of written Greek literature—the Iliad and the Odyssey—Heracles is mentioned only a handful of times. By the end of the eighth century BCE or the beginning of the seventh, he had become almost ubiquitous in Greek mythology, appearing everywhere as a successful warrior and prolific slayer of monsters.

Yet the myth of Heracles does not seem to have assumed its standard form until around the end of the seventh century BCE. This is when the poet Pisander of Rhodes wrote his Heraclea, a major early epic on the myths of Heracles (which now survives only in fragments). Pisander introduced or consolidated all the most famous features of the Heracles myth: it was Pisander who gave Heracles his famous club and lion skin and fixed the number of Heracles’ “labors” at twelve.[1]

Hercules and the Hydra by Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1475)

Uffizi Gallery, Florence / Google Arts and CulturePublic DomainThe Heracles of the Shield of Heracles represents the hero just as these new developments were taking shape. In this poem, however, Heracles fights like the heroes of Homer, with shield, spear, and chariot; the club and lion skin do not yet come into play.

Interestingly, while the club and lion skin eventually became canonical, Heracles’ shield—so exquisitely described by the author of the Shield of Heracles—never did. All the same, the poem still gives us a fascinating portrait of Heracles at an early stage in the development of his myth—almost, though not quite, the Heracles we know today.

Synopsis

In just under 500 lines of verse, the Shield of Heracles tells of a battle between Heracles and Cycnus. Its most important passage (which takes up nearly half of the poem) is a description, or ekphrasis, of the magnificently decorated shield that Heracles carries into battle.

Heracles’ Genealogy (1–56)

The Shield of Heracles begins by recounting the hero’s genealogy. We hear of how Zeus, the king of the gods, and the warrior Amphitryon both slept with Amphitryon’s wife Alcmene on the same night. This caused Alcmene to give birth to twins with different fathers: the stronger one—Heracles—was the son of Zeus, while the more ordinary one—Iphicles—was the son of Amphitryon.

This passage seems to have been taken from the Catalogue of Women, a long genealogical epic also attributed (probably incorrectly) to Hesiod.

Battle Preparations (57–138)

Many years later, Heracles and his nephew Iolaus set out to meet Cycnus, a son of the war god Ares, in battle. This Cycnus had angered Apollo by robbing travelers on their way to his oracular sanctuary at Delphi. Encouraged by Athena, Heracles and Iolaus prepare to face Cycnus and Ares.

The Shield of Heracles (139–321)

As Heracles arms himself for battle, the narrator pauses to describe his beautiful shield, forged by the smith god Hephaestus himself. The shield features magnificently carved scenes involving gods, warriors, beasts, and monsters.

The Battle (322–480)

With Iolaus as his charioteer, Heracles rides out to meet Cycnus. After a brief fight, Heracles prevails. He then fights Cycnus’ father Ares and wounds him with the help of Athena. The gods return to Olympus, Heracles claims victory, and Cycnus is buried.

The “Ludovisi Ares,” second-century CE Roman copy of Greek original from ca. 320 BCE

Wikimedia Commons / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainStyle and Composition

The Shield of Heracles is believed to have been primarily composed in the first few decades of the sixth century BCE. However, its first 56 lines, which detail Heracles’ genealogy, seem to have been taken from a different epic, the Catalogue of Women.

Like the Shield of Heracles, the Catalogue of Women was attributed to Hesiod in antiquity. But also like the Shield, the Catalogue is now thought to have been written by a considerably later author. This does not necessarily mean that the two poems are the work of the same author, though they do seem to have been written around the same time.[2]

Like the epics of Homer or the genuine epics of Hesiod, the Shield of Heracles follows the basic conventions of early Greek epic poetry: it employs dactylic hexameter and an elevated, artificial diction, which does not appear to have corresponded to any spoken dialect of ancient Greek. The battles, speeches, and detailed descriptions found in this brief poem have stylistic parallels with other Greek epics.

Themes

The main theme of the Shield of Heracles—its raison d’être, so to speak—is the meticulous description of Heracles’ shield, which takes up most of the central half of the epic and gives the poem its title.

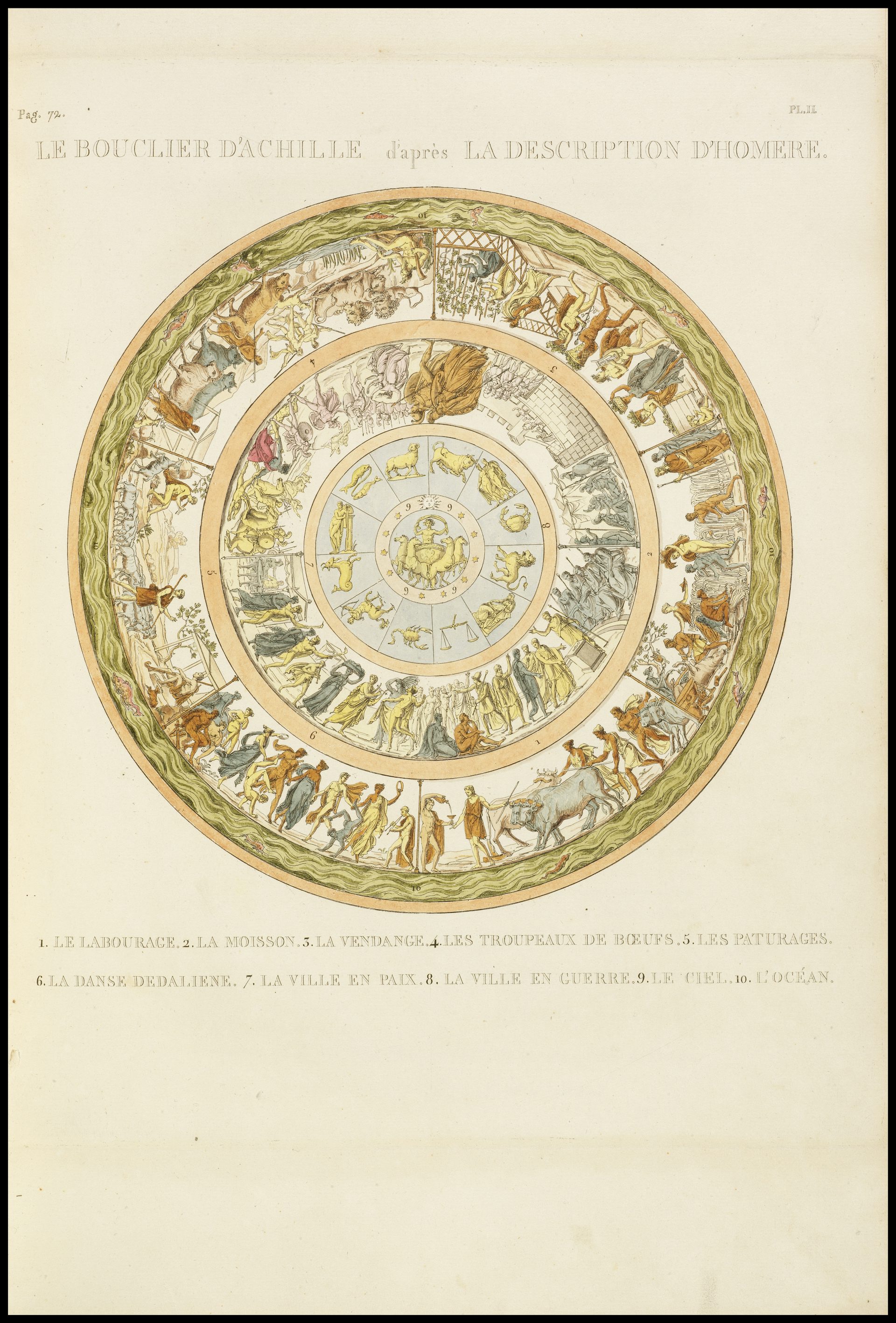

This type of detailed description of an object—known as ekphrasis in Greek—was an important trope in ancient Greek and Latin literature. Perhaps the most famous example of ekphrasis is the description of Achilles’ shield in Book 18 of Homer’s Iliad. Unsurprisingly, the portrayal of Heracles’ shield here owes a great deal to Homer’s earlier text.

Hand-colored etching of the shield of Achilles according to the description of Homer by Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy (1814)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThere are some similarities between the two shields, of course: both were fashioned by Hephaestus, the god of the forge, and both represent scenes from every aspect of life. But the shield of Heracles interprets life somewhat differently than the shield of Achilles. With Heracles, there is a stronger emphasis on the terrifying and the gruesome: we are presented with fearsome divine personifications such as Phobos (Fear) and Eris (Discord), animals such as snakes, boars, and lions, monsters such as Centaurs, and even gods at war.

There are also more peaceful scenes of human life and society, but the author of the Shield of Heracles has a definite taste for the macabre (though some parts of the description were likely added by later poets). Take the shield’s depiction of the war god Ares:

And on the shield stood the fleet-footed horses of grim Ares made of gold, and deadly Ares the spoil-winner himself. He held a spear in his hands and was urging on the footmen: he was red with blood as if he were slaying living men, and he stood in his chariot. Beside him stood Fear and Flight, eager to plunge amidst the fighting men.[3]

This interest in the macabre is what ultimately sets the author of the Shield of Heracles apart from the other epic poets on whom he is drawing (especially Homer).[4] Many themes in the text—including the clash of heroic warriors, the intervention of the gods in human affairs, and the importance of piety—are typical of the time and the genre. But the poet’s imagery marks him as a true individual (albeit an individual whose name we do not know).

Reception

The Shield of Heracles never achieved the popularity of the Homeric epics or the genuine Hesiodic epics (the Theogony and the Works and Days).[5] Nonetheless, the poem does appear to have been reasonably popular in antiquity. Its influence was strongly felt in sixth and fifth century BCE vase painting, with many vases representing the battle between Heracles and Cycnus as described in the short epic.[6]

The ekphrasis of Heracles’ shield may have also influenced scenes in later ancient literature, such as Virgil’s description of the shield of Aeneas in Book 8 of the Aeneid (though the influence of Homer was almost certainly greater).[7]

But the Shield of Heracles was quickly forgotten, overshadowed by other works of greater renown. It was regularly copied and printed throughout European history, but certainly not prized in the same way as the genuine epics of Hesiod. Today it is almost never read except by a few scholars and specialists.

Translations

Translations of the Shield of Heracles are usually found together with the Theogony and the Works and Days (the genuine works of Hesiod). The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful translations:

Evelyn-White, H. G., trans. Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914: A rather old-fashioned prose translation. Can be found in the public domain and thus remains an accessible option.

Lattimore, Richmond, trans. Hesiod: The Works and Days, Theogony, The Shield of Herakles. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959: Old but still highly-regarded translation in non-metrical, non-rhyming verse.

Athanassakis, Apostolos N., trans. Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Shield. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983: Readable free verse translation with commentary.

Most, Glenn, trans. Hesiod, Vol. 2: The Shield, Catalogue of Women, Other Fragments. Loeb Classical Library 503. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007: A very accurate, readable new prose translation, replacing Evelyn-White’s older translation in the Loeb Classical Library series.

Powell, Barry, trans. The Poems of Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, and the Shield of Heracles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017: Accessible verse translation, complete with helpful annotations.