Scylla

Scylla and Glaucus by Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1636).

Musée Bonnat-HelleuPublic DomainOverview

Scylla was a nightmarish monster of obscure origins. The most common description gave her the body and head of a woman, six long serpentine necks (each ending in a mouth with three rows of teeth), twelve feet, and six dog heads growing out of her waist.

Scylla lived in the cliffs on one side of a narrow strait, just opposite the whirlpool Charybdis. Any sea creatures or sailors forced to cross the strait needed to make a terrible choice: either pass by Charybdis and risk being sucked into the sea, or pass by Scylla and become a meal for the six darting heads. Scylla featured most famously in the myth of Odysseus’ wanderings.

In the earliest traditions, Scylla was simply a monster, born of other monsters. But later sources sometimes claimed that Scylla was originally a beautiful nymph who was transformed into a monster by an envious goddess.

Etymology

The name “Scylla” may be related to the Greek words skylax, meaning “puppy,” and skylion, meaning “dogfish.”[1] There may also be a connection with the verb skyllō, “to tear apart.” Sure enough, Scylla was imagined as a monster with both dog and fish features who tore apart her victims.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Scylla Σκύλλα Phonetic

IPA

[SIL-uh] /ˈsɪl ə/

Attributes

Locale

Scylla lived in the cliffs of a narrow strait, directly opposite the whirlpool Charybdis. Consequently, anything that passed through the strait—be it sea creature or ship—was doomed to be either swallowed up by Charybdis or attacked by Scylla. The location of this strait was originally said to be somewhere in the west but was later identified with the Strait of Messina, which separates the island of Sicily from mainland Italy.[2]

Appearance

The earliest description of the monster Scylla comes from Homer’s Odyssey:

Her voice is indeed but as the voice of a new-born whelp, but she herself is an evil monster, nor would anyone be glad at sight of her, no, not though it were a god that met her. Verily she has twelve feet, all misshapen, and six necks, exceeding long, and on each one an awful head, and therein three rows of teeth, thick and close, and full of black death. Up to her middle she is hidden in the hollow cave, but she holds her head out beyond the dread chasm, and fishes there, eagerly searching around the rock for dolphins and sea-dogs and whatever greater beast she may haply catch, such creatures as deep-moaning Amphitrite rears in multitudes past counting. By her no sailors yet may boast that they have fled unscathed in their ship, for with each head she carries off a man, snatching him from the dark-prowed ship.[3]

Other sources offered variations on this description. Apollodorus, for example, added that Scylla had six dog heads ringing her waist and that her twelve “misshapen” feet were actually dog feet.[4] Hyginus wrote that Scylla was a woman from the waist up, a fish from the waist down, and had six dogs coming out of her middle.[5] Other authors, meanwhile, gave Scylla six heads of various animals (not only dogs),[6] while still others gave her only three heads.[7]

Iconography

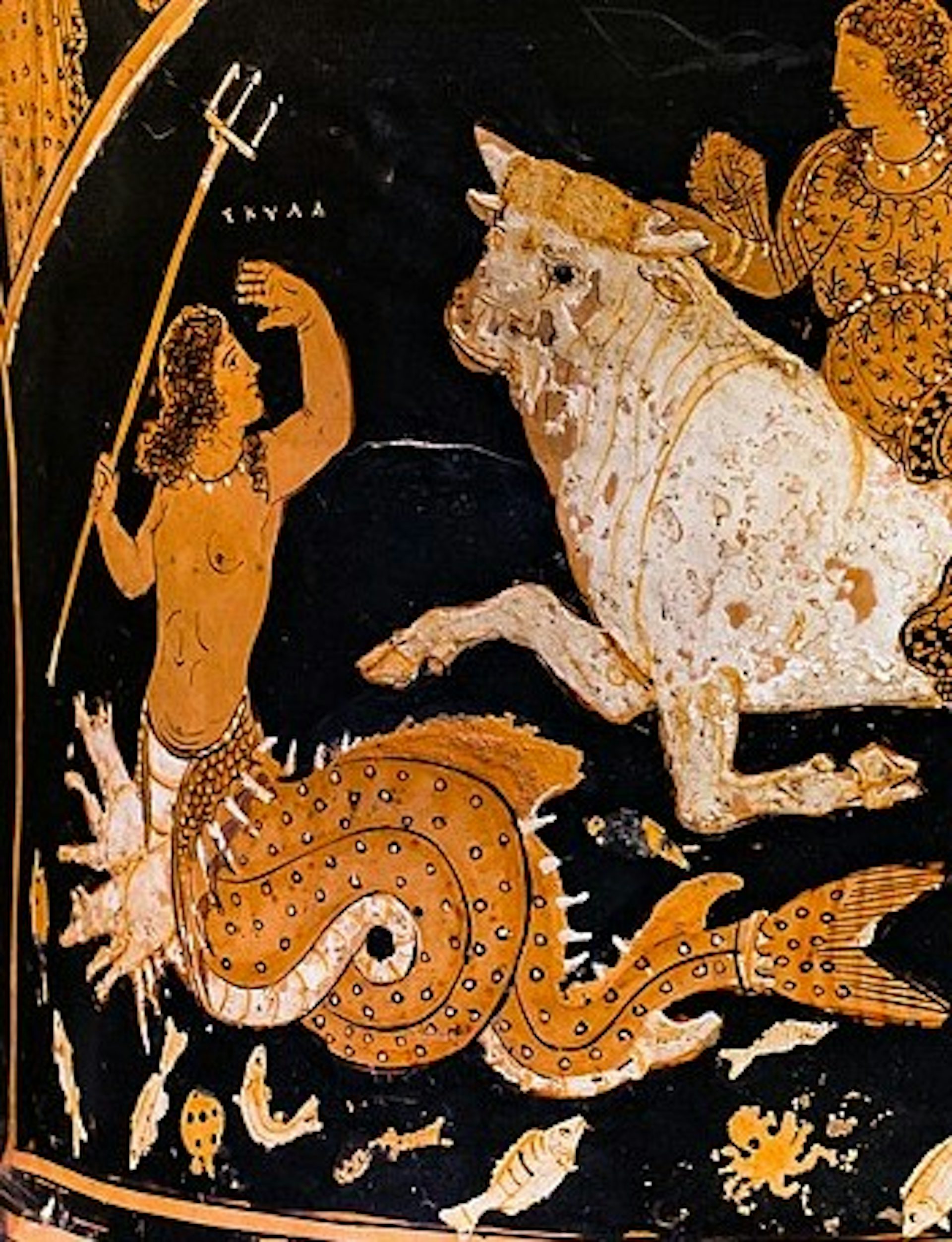

In the visual arts, by contrast, Scylla was usually represented as a young and beautiful maiden with mermaid-like features. This gentler Scylla also had fewer serpent necks and dog heads than in the literary tradition (usually three rather than six).[8]

Paestan red figure calyx-crater showing Scylla wielding a trident (ca. 350 BCE). Museo Archeologico Nazionale del Sannio Caudino, Montesarchio.

ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0Family

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

- Apollo, Deimos, Phorcys, Trienos, Triton, Typhoeus, Tyrrhenus

- Crataeis, Echidna, Hecate, Lamia

Mythology

Origins

The earliest mythical traditions had little to say about Scylla’s origins; in the Odyssey, for example, she was introduced simply as a monster born to the mysterious Crataeis. But in a tradition devised by later authors, Scylla was said to have originally been a beautiful Naiad who was transformed into a monster by a jealous goddess.

There are two versions of this story. In one, Scylla was the love interest of the sea god Glaucus. But Scylla did not return these affections; in fact, she was horrified by Glaucus’ appearance (he was part fish). Desperate, Glaucus begged the sorceress Circe to help him win Scylla’s love, but Circe was in love with Glaucus herself. Thus, instead of giving Scylla a love potion, she poisoned the water in which she was bathing. This caused Scylla to immediately transform into the part-fish, part-snake, part-dog monster of myth.[21]

Glaucus and Scylla by Bartholomeus Spranger (1580–1582). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThere is a variant of this story in which Scylla was the love interest of Poseidon, not Glaucus. In this version, Scylla was transformed into a monster by Poseidon’s wife Amphitrite.[22] In some traditions, Poseidon ultimately transformed Scylla into a cliff.[23]

Scylla and the Heroes

Scylla featured in the myths of several heroes (most famously Odysseus), whose adventures brought them to her dangerous lair.

Jason and the Argonauts

When Jason and the Argonauts were sailing back from Colchis with the Golden Fleece, they came close to being destroyed by Scylla and Charybdis. The route they had taken to get to Colchis—through the Clashing Rocks—had been closed off, and the only way back home was through the strait of Scylla and Charybdis.

But the goddess Hera, who loved Jason, was determined to preserve the hero from harm. She ordered Thetis and the other Nereids to guide the Argo through the strait so that they would be neither swallowed up by Charybdis nor torn apart by Scylla.[24]

Odysseus

Odysseus, one of the Greek heroes of the Trojan War, was forced to sail through the strait of Scylla and Charybdis on his voyage home from Troy. He was not so lucky in his encounter with Scylla.

Before making this passage, Odysseus was warned by the sorceress Circe to sail closer to Scylla so as to put as much distance as possible between himself and Charybdis: for while Scylla would kill six of his men—one for each of her heads—Charybdis would destroy his whole ship and kill every crew member.

Circe also gave Odysseus two further pieces of advice: first, not to arm himself or try to fight Scylla, as doing so would only give the monster a chance to pounce a second time and kill another six men; and second, to pray to Scylla’s mother, Crataeis, to hold off her daughter from pouncing more than once.

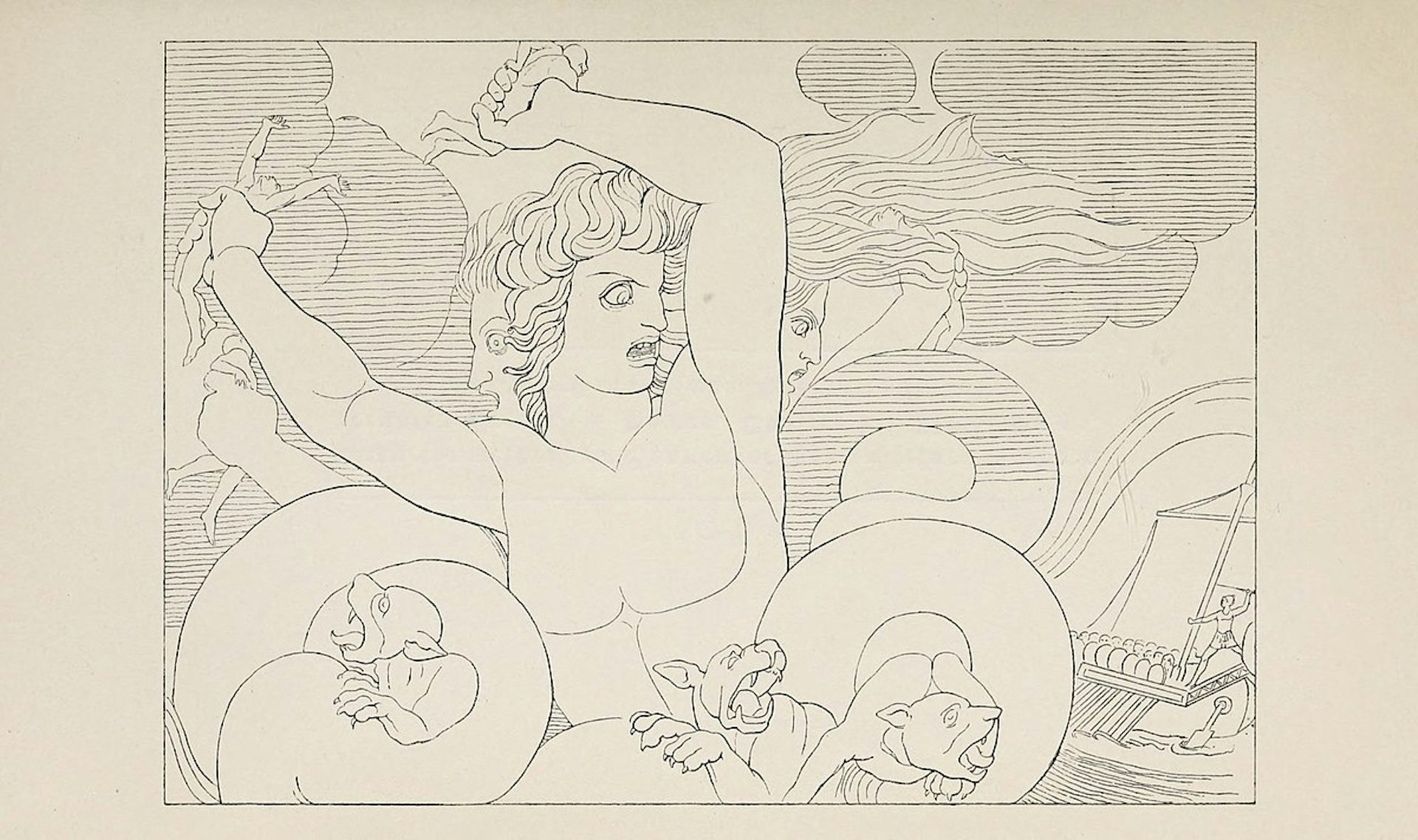

Illustration of Scylla attacking Odysseus and his crew by John Flaxman (1910).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOdysseus did as Circe instructed. When the time came, he did not give his men a chance to fight against Scylla, and six of them were snatched from the ship in each of the monster’s six mouths. Odysseus could do nothing but watch in horror as Scylla dragged his men to her rocky lair and devoured them.[25]

Aeneas

The hero Aeneas, who fought on the side of Troy during the Trojan War, also came close to encountering Scylla during his wanderings, though he was ultimately able to avoid the monster. According to Virgil, the Trojan prophet Helenus advised Aeneas on a detour that would allow him to sail around Scylla entirely.[26] But in another version of the story, recounted by Virgil’s younger contemporary Ovid, no detour was needed: Scylla had been transformed into a reef by the time Aeneas sailed by her.[27]

Death (and Resurrection)

In some traditions, Scylla was killed by Heracles. After Heracles had retrieved the giant cattle of Geryon as his tenth labor, he was forced to pass through Scylla’s strait. True to form, Scylla ate some of the cattle Heracles was bringing with him. Equally true to form, Heracles got his revenge by killing Scylla.

But Scylla did not stay dead for long. She was soon resurrected by her powerful father (likely envisioned in this tradition as Phorcys).[28]

Guardian of the Underworld

Roman poets sometimes imagined that Scylla—or even multiple Scyllae—guarded the gates of the Underworld along with other mythical monsters, including the Hydra, the Chimera, and the Centaurs. How Scylla (or the other Scyllae) acquired this role is unclear.[29]

Pop Culture

Scylla has been featured a few times in modern pop culture. She makes notable appearances in the 1997 miniseries The Odyssey and in Rick Riordan’s The Sea of Monsters, the second novel in the Percy Jackson and the Olympians series (adapted into a movie in 2013).