Python

Apollo and the Python by Cornelis de Vos, after Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1636–38)

Museo Nacional del PradoPublic DomainOverview

Python was a huge, monstrous serpent, sometimes said to be a son of Gaia. In many traditions, he served as the original keeper of the oracle at Delphi. When the god Apollo was still young—possibly just a baby—he chased Python down and slew him with his bow and arrows. Afterwards, Apollo established the oracle at Delphi on the site, destined to become one of the most important oracles of antiquity.

The myth of Python existed in many variants and evolved over time. As a result, there are conflicting accounts of the motivation for the battle between Python and Apollo, the serpent’s sex, and even its name.

Etymology

The etymology of “Python” (Greek Πύθων, translit. Pýthōn) is uncertain, though that name has been used to designate the serpent slain by Apollo since at least the sixth century BCE.[1]

The ancient Greeks derived the name “Pytho,” another name for Delphi, from the verb πύθομαι (pýthomai), meaning “to rot, decay”; they believed that the site got its name from the rotting corpse of Python after it was slain by Apollo. According to a kind of circular logic, they presumably derived the serpent’s name from the same word.

Yet it is also possible that the name “Python” comes from the Greek word πυνθάνομαι (pynthánomai), meaning “to learn, inquire.”[2] Python would translate as “the learned one” or even “the enlightened one”—a far cry from “the rotting one.”

Yet another possibility (albeit a more far-fetched one) is that Python’s name was derived from the Egyptian site of pr-jtm, commonly known as “Pithom.” There is evidence that the Egyptian god Atum (from which the site derived its name) was worshipped there in the form of a serpent, perhaps suggesting a connection with the serpent Python.[3]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Python Πύθων (translit. Pýthōn) Phonetic

IPA

[PAHY-thon] /ˈpaɪ θɒn/

Alternate Names

Though “Python” became the most familiar name for the snake that Apollo killed at Delphi, it was not the only one attested in ancient sources. An important alternate name was Delphynes.[4] There are also accounts of a female serpent-monster named Delphyne, perhaps representing yet another variant of Python (who was indeed female in the earliest sources for the myth).[5]

Attributes

The myth of Python changed and developed over time; as a result, there are several conflicting versions of the creature.

The only consistent defining attribute of Python was that it lived at or near Delphi (often in a cave).[6] Its name varied, and many sources did not refer to it by any name at all.

Even the creature’s sex was uncertain. In fact, though Python was depicted as male in all sources that used that name for him, there were other important traditions in which the serpent slain by Apollo at Delphi was female. In the earliest known account of the myth, for example, Apollo battled an unnamed female snake.[7] Other sources spoke of two serpents, a male and a female, called Delphyne and Delphynes.[8] By the fifth century BCE, however, the serpent that Apollo fought was almost always known as Python, and was almost always male.[9]

Apollo and Python by Artus Quellinus the Elder (17th century). Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium.

King Baudoin FoundationCC BY-SA 4.0Descriptions of the creature’s appearance were more consistent. Python was always represented as a very large serpent. Some authors embellished by adding specific features to his description, such as dark eyes, a green or blue body, or a threefold tongue. Many expressed Python’s unbelievable size by remarking that he covered the mountains or enclosed them in his coils (indeed, this became something of a commonplace in ancient poetry). A late writer, Menander Rhetor, gave an especially vivid description:

[Mount Parnassus] it covered with its spirals and coils, and nothing of the mountain remained bare. It held its head over the very crest, rearing up towards the heaven itself. When it needed to drink, it consumed whole rivers; when it needed to eat, it annihilated whole flocks.[10]

It is surprisingly rare to find representations of Python in ancient art. He did, however, become more popular among artists during the Imperial period (27 BCE–476 CE). Though his size varied in art, Python was always shown as a large serpent, echoing his portrayal in literature.[11]

Family

Most sources do not say anything about Python’s parentage. Those that do, however, make him the child of Gaia, the earth goddess, most likely without a father.[12]

Family Tree

Parents

Mother

Mythology

Origins

The origins of Python are obscure. Initially, the serpent that came to be known as “Python” seems to have been a nameless female serpent that terrorized the lands around Delphi; this is what we find in the third Homeric Hymn (the Homeric Hymn to Apollo).

Eventually, though, more and more sources made the serpent male and gave him the name “Python” (though the variant “Delphynes” is also attested). Others added that the serpent was the child of Gaia, the primordial goddess of the earth.

Python was closely associated with the oracular site of Delphi, located in central Greece. An early tradition made Python the guardian of the oracle during the primordial era, when it belonged to Gaia and was operated by the Titaness Themis.[13] There are a few variations of this tradition. In one, Python was not only the guardian but actually the owner of the oracle.[14] In another, he shared the oracle with the Titan Cronus, father of Zeus and the other Olympians.[15]

Ruins of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, Greece (fourth century BCE), the site said to have once been held by Python.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Other traditions made Python more of a villain. Some said that, far from guarding the oracle of Delphi, he laid waste to the region.[16] Others, though, said that the region was already a wasteland when Python arrived and took over.[17] The third Homeric Hymn, perhaps to make the creature even more terrible, added that when Hera brought forth the monster Typhoeus, she gave it to the serpent of Delphi (here unnamed) to raise.[18]

The Battle with Apollo

Ancient traditions disagreed on the reasons for the battle between Apollo and Python. There are three main versions:

In one version, Apollo’s goal was simply to take over Delphi. Since Python was the current owner or guardian of the oracle, Apollo needed to kill him first.[19]

In another version, Python had been terrorizing Delphi, and Apollo wanted to free the region from the cruel monster.[20]

In yet another version, Python had pursued Leto when she was pregnant with Apollo and his twin Artemis. According to this account, the creature had been sent by Hera, who was jealous that her husband Zeus had slept with Leto. But Python may have pursued Leto after learning through his prophetic powers that he would be killed by one of Leto’s children. In either case, as soon as Apollo was born—while he was still a baby in his mother’s arms, in fact—he fought Python as revenge for chasing his mother.[21]

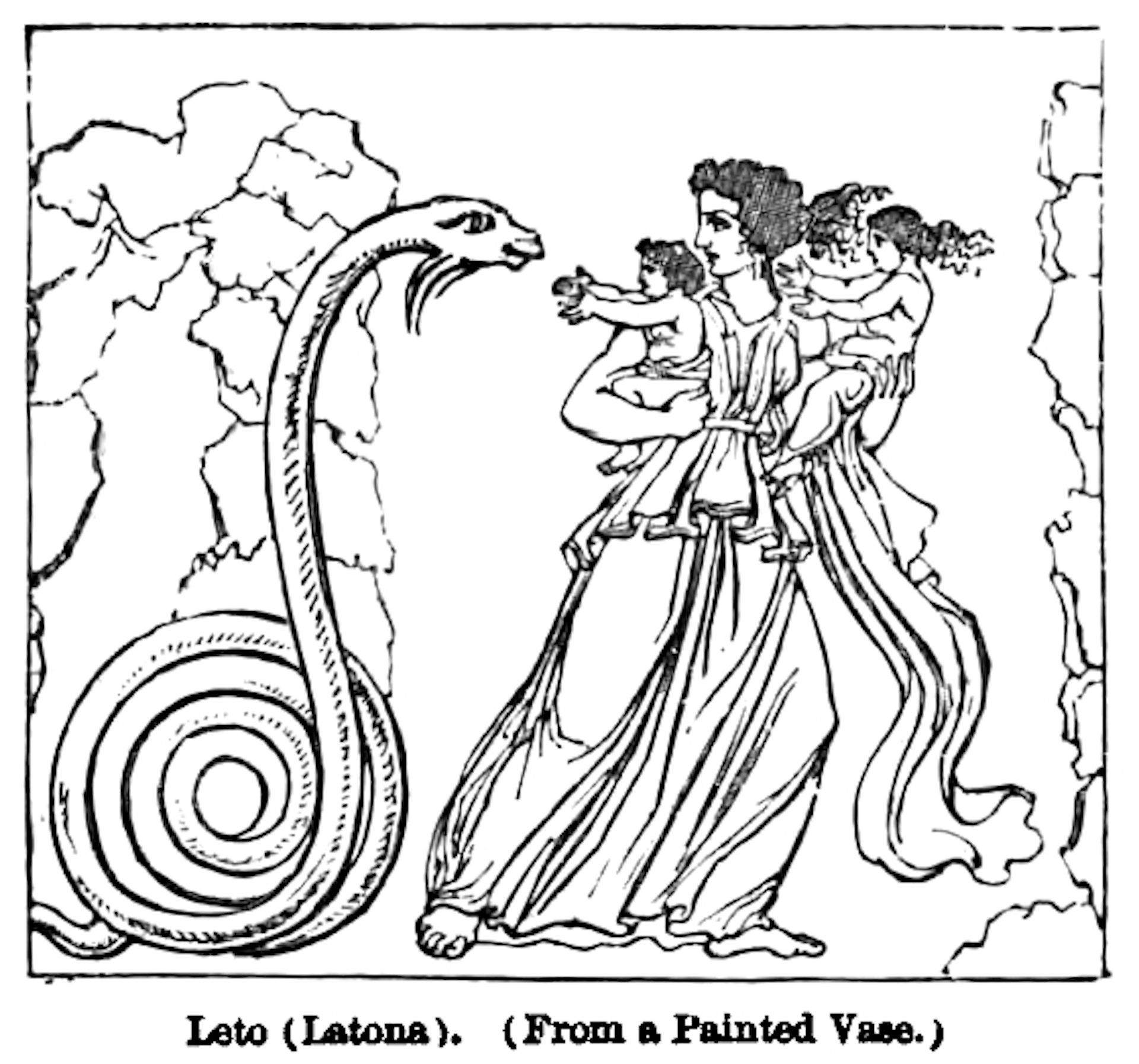

Drawing after a lost Apulian red figure neck amphora showing Leto with Apollo and Artemis pursued by Python (early 4th century BCE).

A Smaller Classical Mythology by William Smith (1882)Public DomainWhatever the reasons for the fight, the battle with Python was the first great act of the young Apollo. In some versions, his sister Artemis fought alongside him.[22] Sources agree that the battle took place either at Delphi[23] or somewhere nearby (Tempe,[24] Tegyra,[25] or Gyrneia[26]), and that Apollo ultimately killed Python with his bow and arrows.[27] The third Homeric Hymn describes the serpent’s fall:

Then she, rent with bitter pangs, lay drawing great gasps for breath and rolling about that place. An awful noise swelled up unspeakable as she writhed continually this way and that amid the wood: and so she left her life, breathing it forth in blood.[28]

After Python was dead, it was sometimes said that Apollo buried the body at Delphi beneath the omphalos, the sacred stone that marked the exact center of the world.[29] But others said that Apollo placed the remains of the serpent in the great tripod of Delphi, which he then covered in the serpent’s own skin.[30]

Apollo Victorious over Python by Pietro Francavilla (1591).

Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainAfter killing Python, Apollo established an oracle at Delphi, where worshippers from all over the Greek world came to honor him. His victory was commemorated in several ways. First, Delphi came to be known as Pytho, while Apollo’s priestess was called the Pythia. Apollo also instituted the Pythian Games, which were celebrated every four years,[31] as well as the feast of Septerion, celebrated every nine years.[32]

Pop Culture

Python continues to appear in modern pop culture, most notably in Rick Riordan’s The Trials of Apollo. In this series of five novels, Apollo has become mortal and must regain control of his oracles from the resurrected Python. In the final book of the series, The Tower of Nero, Python is at last defeated.