Phoenix

The bird Phoenix by Cornelis Troost (ca. 1720–50).

RijksmuseumPublic DomainOverview

The Phoenix, a creature with links to Egyptian mythology, was a bird that resembled a fiery eagle, with red and gold plumage. Its mythology primarily focused on its death and subsequent rebirth. In the most familiar account, it would live for 500 years, after which it would burn itself on the altar of the sun in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis and be reborn from its own ashes.

Ever since antiquity, the Phoenix has been a potent symbol of death and resurrection. Its myth remains popular today.

Etymology

The etymology of “Phoenix” (Greek Φοῖνιξ, translit. Phoînix) is uncertain. The name is identical to a Greek word that can mean “palm tree,” “reddish-purple,” or “Phoenician”; as a result, scholars since antiquity have sought creative connections between the Phoenix and the other diverse meanings of the word φοῖνιξ (phoînix). The name can be interpreted as anything from “shining bird” to “reddish-purple bird,” “palm tree bird,” or “Phoenician bird,”[1] but there is no clear consensus on which is the “correct” etymology.

Scholars agree that the word φοῖνιξ (phoînix) is quite old, existing in some form since the Greek Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1100 BCE); it appears in the Linear B script (used before the adoption of the Greek alphabet) as po-ni-ke. Even at this early date, the word possessed multiple meanings, including “palm tree” and “griffin.”

Some scholars have suggested that the name of the Phoenix came from the bird’s Egyptian name, benu. This word in turn seems to have been derived from the Egyptian verb wbn, meaning “to shine.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Phoenix Φοῖνιξ (translit. Phoînix) Phonetic

IPA

[FEE-niks] /ˈfi nɪks/

Attributes

Locales

The Phoenix was most closely associated with Egypt and the sacred city of Heliopolis (“Sun City”).[2] But it was also connected with other exotic lands: some sources claimed that it lived or died in Arabia,[3] Ethiopia,[4] Phoenicia,[5] Assyria,[6] or the Far East/India.[7]

A few sources wrote that the Phoenix lived in an Eden-like grove sacred to the sun.[8] But there were other traditions, too, including one in which the Phoenix lived in a special palm tree in Egypt, the syagrus palm, which died and was reborn with the Phoenix.[9]

Appearance

The first author to give a full description of the Phoenix was Herodotus, a fifth-century BCE historian. Herodotus based his account on pictures of the Phoenix that he claimed to have seen in Egypt, which showed the bird with gold and red plumage, “most like an eagle in shape and size.”[10]

Illustration of the Phoenix from Justin Bertuch’s Bilderbuch für Kinder (1806).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainMany later sources also gave reports of the Phoenix’s appearance. According to Pliny the Elder, for example, the Phoenix

is of the size of an eagle, and has a brilliant golden plumage around the neck, while the rest of the body is of a purple colour; except the tail, which is azure, with long feathers intermingled of a roseate hue; the throat is adorned with a crest, and the head with a tuft of feathers.[11]

The Phoenix’s crest became an important attribute of the bird in many sources.[12] Some added that the feathers of the Phoenix’s crest resembled the rays of the sun or even that the creature was crowned with a kind of colorful ring, halo, or star representing the sun.[13]

A particularly impressive description of the Phoenix can be found in the Exodus, a fragmentary Greek tragedy by an obscure Jewish poet named Ezekiel who seems to have lived around the third century BCE:

[The Phoenix] was about twice the size of an eagle

And had multi-colored wings.

His breast was purplish

And his legs red. From his neck

Saffron tresses hung beautifully.

His head was like that of a cock.

He gazed all around with his yellow eye

Which looked like a seed.

He had the most wonderful voice.

Indeed, it seemed that he was the king of all the birds.

For all of them

Followed behind him in fear.

He strode in front, like an exultant bull,

Lifting his foot in swift step.[14]

Thus, it is clear that there were conflicting accounts of the Phoenix’s appearance. Some sources said it was about the size of an eagle, while others claimed it was much larger—one even described the Phoenix as the size of an ostrich.[15] All agreed that the creature had magnificent and colorful plumage (it was often compared to a peacock), though the specifics differed: some said the Phoenix had only gold and red feathers, while others added purple, yellow, green, or blue plumage.[16]

Sex

Since the Phoenix did not reproduce sexually, the question of its sex—or if it even had a sex at all—was open to debate. Ancient authors usually left the question unanswered. A handful of authorities were convinced that the Phoenix did have a definite sex (one even made the strange claim that the Phoenix proved its identity to the priests of Heliopolis by displaying its genitalia), but did not specify or claim to know whether that sex was male or female.[17] Others speculated that it could be male, female, asexual, or bisexual.[18]

Food

Like its other attributes, the Phoenix’s diet was unusual. Some said it never ate at all (or at least, was never seen eating).[19] Others said that it did not eat ordinary food but survived solely on aromatic plants and spices like frankincense,[20] that it was fed by the heat of the sun and by the wind,[21] or that the young Phoenix was fed with miraculous dewdrops from heaven but no longer ate once it reached maturity.[22]

Lifespan

Perhaps the most distinctive attribute of the Phoenix was its impressively long lifespan, though not all authorities agreed on the exact length of that lifespan. Many simply reported that the Phoenix lived a very long time.[23]

According to the most common tradition, the Phoenix lived for 500 years.[24] However, the Roman historian Tacitus pointed out that some sources had tallied the creature’s lifespan at 1,461 years.[25] Others gave its age as 1,000 years,[26] 540 years,[27] 654 years,[28] or 7,006 years.[29] The earliest source we have on the Phoenix is a fragment of a poem attributed to Hesiod, in which an unnamed Naiad claims that the bird lived for 972 human lifetimes:

Nine generations long is the life of the crow and his cawing,

Nine generations of vigorous men. Lives of four crows together

Equal the life of a stag, and three stags the old age of a raven;

Nine of the lives of the raven the life of the Phoenix doth equal;

Ten of the Phoenix we Nymphs, daughters of Zeus of the aegis.[30]

If we assume a human generation lasts approximately 30 years (the standard in most ancient Greek sources), this would mean that Hesiod’s Phoenix lived for a monumental 29,160 years (or thereabouts).

Death and Rebirth

After the Phoenix had completed its lengthy lifespan—however long that was—it was immediately reborn. Once again, there was considerable disagreement surrounding the death and rebirth of the Phoenix. The various traditions tended to fall into two main camps.

In one tradition, the old Phoenix would build a nest from aromatic plants and spices. It would then burst into flames and burn together with its nest; from the ashes, a new Phoenix would arise.[31] According to some authorities, the Phoenix would only build its nest in Egypt.

Illustration of the Phoenix burning in its nest from the Aberdeen Bestiary (12th century).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn a less familiar (but still important) rival tradition, the old Phoenix would simply lie in the nest it had built until it died and decomposed. A new Phoenix would eventually be born from the remains, emerging (according to some) as a worm. As soon as the new Phoenix had grown strong enough, it would carry what was left of its predecessor to Heliopolis in Egypt to rest upon the altar of the sun god.[32]

Iconography

The Phoenix rarely appeared in ancient Greek art. However, representations of the creature became more common during the Hellenistic (323–31 BCE) and Roman (27 BCE–476 CE) empires, when Egypt was controlled first by the Macedonians and then by the Romans. For example, the Phoenix did appear on some coins of the Roman Empire, which typically showed the bird with a halo or crown topped by the rays of the sun.[33]

A coin (Roman nummus) showing the emperor Constans on the obverse and a Phoenix standing atop a globe on the obverse. Minted in Trier between 348 and 350 CE to commemorate Rome’s 1,000th anniversary.

Portable Antiquities SchemeCC BY 2.0History

Origins

The Greeks themselves generally believed that the Phoenix came from Egypt.[34] Modern scholars, however, are less certain that the Egyptian benu had a direct or straightforward influence on the development of the Phoenix myth in Greece.[35]

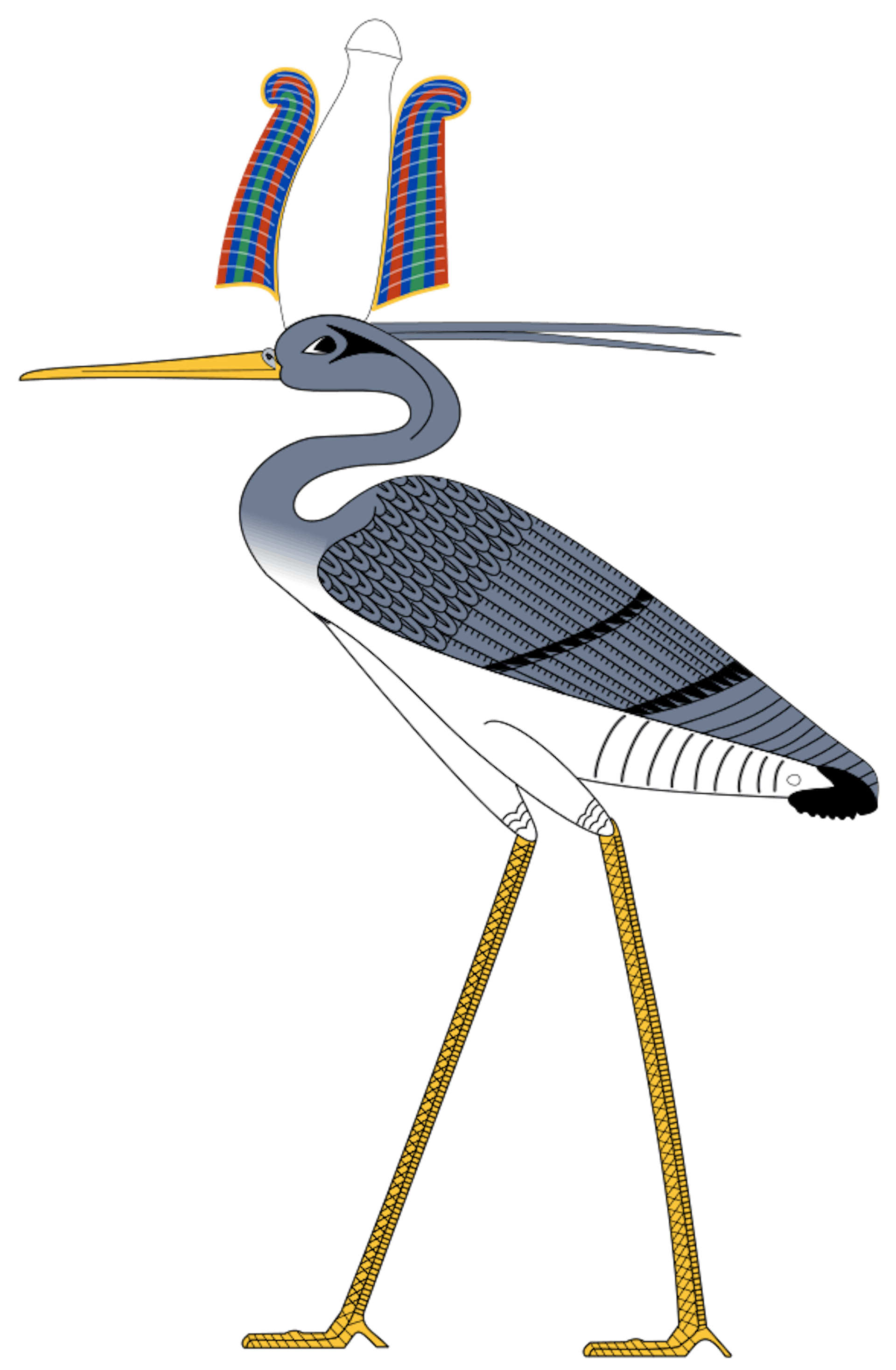

There were, of course, similarities between the Phoenix and the benu: both were connected with the cult of the sun god in Heliopolis, both were born spontaneously, and both represented birth, creation, and time cycles.

But there were also important differences. The Egyptian benu usually looked something like a heron with two large feathers on the back of its head—not quite the huge, eagle-like, and rainbow-colored bird of Greek mythology. The benu was often depicted perching on a sacred willow tree in the temple of the sun in Heliopolis. And though the benu was, like the Phoenix, born asexually or spontaneously, the details of its birth are unknown from any Egyptian source.[36]

Illustration of the Egyptian Benu based on New Kingdom tomb paintings.

Jeff DahlCC BY-SA 4.0The Greeks and Egyptians were not the only civilizations with a resurrecting sun bird. Other cultures—whether independently or inspired by their neighbors’ lore—spoke of similar creatures. The Romans, of course, adopted the Phoenix directly from the Greeks. But Judaism also has a kind of Phoenix, the ḥôl, which first appeared in the Book of Job[37] and was further developed in later rabbinical sources. According to this tradition, while living in the Garden of Eden, Eve offered the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge not only to Adam but to all the animals; the only animal to refuse was the ḥôl, which received eternal life as its reward.[38]

Sightings

A few historical sightings of the Phoenix were reported in ancient texts. Pliny the Elder, citing various sources, wrote that the Phoenix was said to have appeared in the years 96 BCE and 36 CE. He added that a Phoenix was brought to Rome during the reign of the emperor Claudius in time for the 800th anniversary of Rome’s founding (47 CE), but that there could be no doubt that “it was a fictitious phoenix only.”[39] Tacitus, a Roman historian, reported that a Phoenix was sighted in 34 CE.[40]

Symbolic Interpretations

Because of its long lifespan, the Phoenix was sometimes connected with the concept of the Great Year, a renewal of the world and the beginning of a new era; according to this tradition, the Phoenix marked the end of one Great Year and the start of a new one.[41] Of course, there was no agreement in antiquity regarding the length of the Great Year, just as there was no agreement on the length of the Phoenix’s lifespan.

To the Greeks as well as the Egyptians, the Phoenix was also a natural symbol of rebirth and creation: its life cycle was always renewed, with the Phoenix resurrecting after it had died (arising, in some traditions, from its own ashes).

The Phoenix was also adopted by early Christians, who viewed it as a symbol of the immortal soul or even the resurrection of Jesus Christ.[42]

Pop Culture

The Phoenix never lost its hold on the public’s imagination and is still widespread in contemporary pop culture.

In literature, Phoenixes can be found in works by C. S. Lewis, J. K. Rowling, Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett, and many others.

The Phoenix has also been popular in music. For example, a Phoenix straddles the top of the logo used by the British rock band Queen. Phoenixes have also featured in numerous songs, album titles, and music videos, not to mention operas.

Performance poster showing the Queen logo.

TheMillionaireWaltzCC BY-SA 4.0The Phoenix—or references to it—has also appeared in film and television. There are several ships in the Star Trek universe named after the Phoenix. In the X-Men franchise, “Phoenix” is the dreaded alter ego of the superhero Jean Grey, while an episode of the TV series Supernatural features a strangely humanoid Phoenix.

Phoenixes are also popular in video games. Egyptian characters in the game Age of Mythology can summon Phoenixes, and various adaptations of the Phoenix can be found in RuneScape, League of Legends, and Sonic Unleashed, among others.

Finally, the Phoenix has many modern namesakes, including the capital city of Arizona.