Phaethon

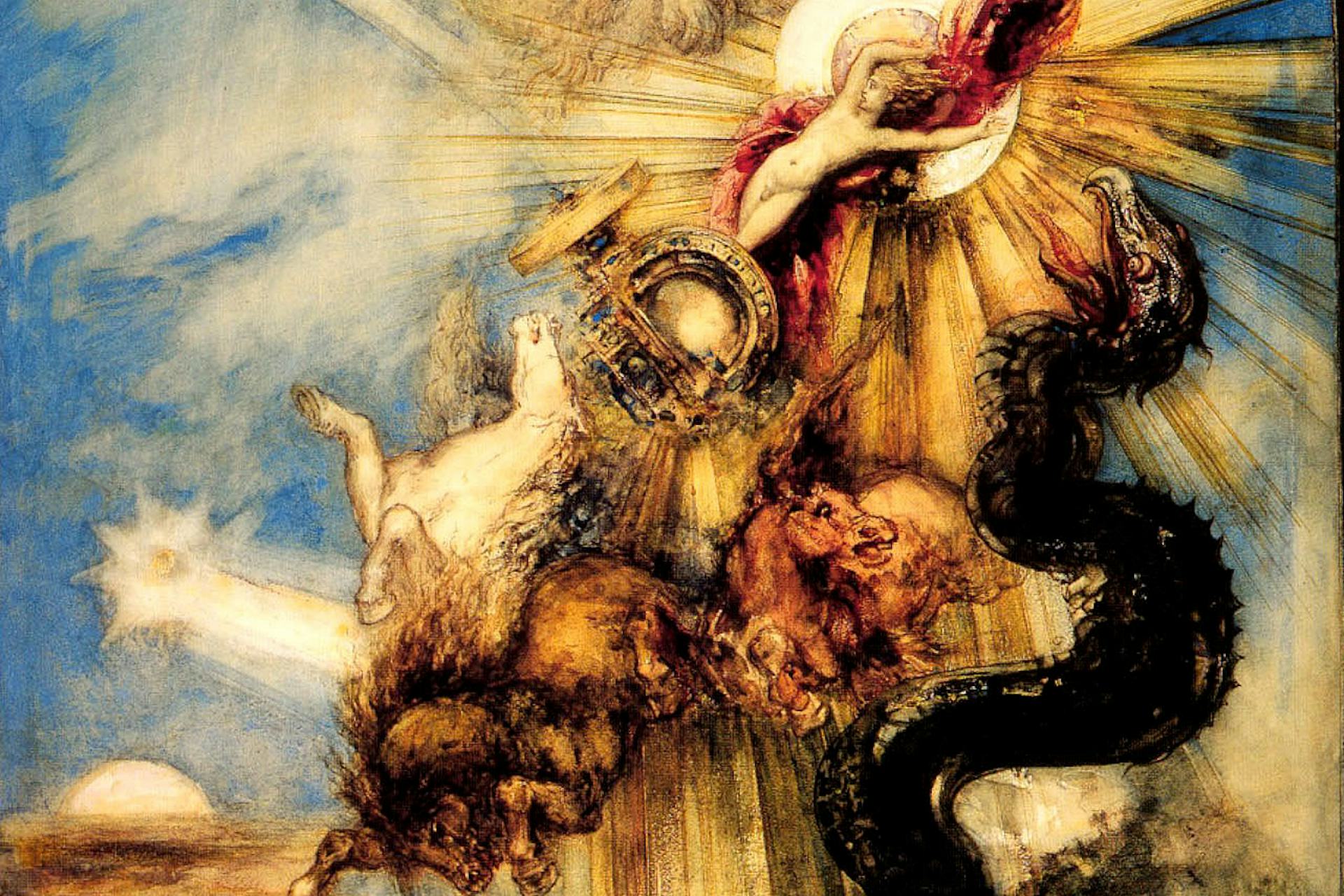

Phaethon by Gustave Moreau (1878)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainOverview

Phaethon was the son of Helios, the god of the sun, and Clymene, an Oceanid. He was raised by his mother alone, but upon discovering his father’s identity, he set out to find Helios’ palace in the Far East. Helios welcomed Phaethon with open arms and agreed to grant his son one request. In response, Phaethon foolishly demanded to drive the chariot of the sun across the sky.

Alas, Phaethon lost control of the unruly horses pulling the chariot; he would have set the whole world on fire had Zeus not killed him with his lightning bolt. Struck down by the king of the gods, Phaethon fell from the chariot into a remote river known as the Eridanus. There, his sisters—the Heliades—mourned for him until the gods took pity on them and turned them into poplar trees.

Etymology

The name “Phaethon” (Greek Φαέθων, translit. Phaéthōn) is the participle of the Greek verb φαίνω (phaínō), meaning “to appear, shine.” Phaethon’s name can thus be translated as “the shining one.” In English, the name is sometimes also spelled “Phaëthon.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Phaethon Φαέθων (Phaéthōn) Phonetic

IPA

[FEY-uh-thuhn] /ˈfeɪ ə θən/

Alternative Names

According to one source, Phaethon’s name was originally Eridanus; it was changed to Phaethon—“the shining one”—due to his fateful ride in the bright chariot of the sun. Meanwhile, the river into which he fell became known by his former name, Eridanus.[1]

Attributes

General

Phaethon’s chief characteristic was his hubris or brashness; though he was only a mortal, Phaethon desired to drive the chariot of the sun, which only Helios (a god) could control. This arrogance led to Phaethon’s downfall.

Iconography

Phaethon rarely appeared in ancient art before the time of the Roman Empire (ca. 27 BCE–476 CE). He was occasionally depicted in vase paintings but was much more popular in sculpture. Artists tended to favor scenes like his meeting with his father Helios or his disastrous ride in the chariot of the sun.[2]

Family

In the most familiar tradition, Phaethon was the son of Helios, the sun god, and an Oceanid (or perhaps a mortal) named Clymene.[3] In other traditions, however, Phaethon’s mother was Prote, the daughter of Neleus,[4] or Rhode, the daughter of Asopus.[5] Most authorities gave him several sisters or half-sisters known as the Heliades (after their father Helios).

One late source, the Roman mythographer Hyginus, made Phaethon the son not of Helios but of Helios’ son Clymenus and the Oceanid Merope.[6]

Red-figure calyx-krater showing Helios riding his chariot out of ocean (ca. 430 BCE), excavated in Puglia, Italy

British MuseumCC BY-SA 4.0Mythology

Origins

Already in antiquity, the myth of Phaethon was sometimes thought to have originated in a genuine cosmic fire caused by the movements of the celestial bodies.[7] Presumably these ancient authors were referring to what we would now call a meteorite impact; some contemporary scholars and geologists have indeed speculated that the Phaethon myth was inspired by such an impact.[8]

The Chariot of the Sun

For the most part, the myth of Phaethon and his disastrous attempt to drive the chariot of the sun is consistent across ancient sources, with only occasional variations.

Phaethon was the son of Helios, the god of the sun, but he was raised by his mother alone, kept far away from his powerful father. As he was entering adulthood, Phaethon decided to go in search of his father.

In some accounts, the vain Phaethon simply wanted to verify that he really was the son of a god. But in another account, which seems to have originated in a lost tragedy by Euripides, Phaethon’s mother sent him to Helios to calm his anxieties about his upcoming wedding.[9]

When Phaethon reached Helios’ magnificent palace, located in the Far East near the rays of the rising sun, Helios greeted him warmly. He promised to grant Phaethon anything he wished. The proud Phaethon demanded to drive the chariot of the sun across the sky for one day. Helios was horrified and begged his son to ask for something else:

I’d fain deny this wish, which thou hast made,

Or, what I can’t deny, wou’d fain disswade.

Too vast and hazardous the task appears,

Nor suited to thy strength, nor to thy years.

Thy lot is mortal, but thy wishes fly

Beyond the province of mortality:

… Let not my son a fatal gift require,

But, O! in time, recall your rash desire;

You ask a gift that may your parent tell,

Let these my fears your parentage reveal;

And learn a father from a father’s care:

Look on my face; or if my heart lay bare,

Cou’d you but look, you’d read the father there.

Chuse out a gift from seas, or Earth, or skies,

For open to your wish all Nature lies,

Only decline this one unequal task,

For ’tis a mischief, not a gift, you ask.[10]

But Phaethon would not be dissuaded. With a heavy heart, Helios turned over the reins of his chariot to Phaethon, carefully instructing him on how to keep the fiery horses in check (in Euripides’ version, Helios actually accompanied Phaethon on his ride).

Phaethon, naturally, was not strong enough to control the chariot or its divine horses. The horses swerved from their path and came close to setting the world on fire.

In an effort to put a stop to this wanton destruction, Zeus struck Phaethon with a lightning bolt—though according to some versions, Phaethon simply fell from the chariot. In either case, Phaethon plummeted to his death, and the gods helped Helios regain control of his chariot.

After Phaethon’s fall, his sisters, the Heliades, searched far and wide for his body. They eventually found him by the Eridanus, a remote river sometimes identified with the Po in northern Italy. The Heliades mourned their brother without rest until the gods took pity on them and turned them into poplar trees, forever weeping tears of amber.[11]

Phaethon was also mourned by Cycnus, the young king of the Ligurians who was Phaethon’s close friend or lover. Cycnus was likewise transformed by his mourning, becoming a swan or a constellation (depending on the source).[12]

Print of the transformation of the Heliades and of Cycnus by Hendrick Goltzius (1590)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainIn another version, Phaethon took the chariot without Helios’ permission, enlisting the help of the Heliades to carry out his task. According to this account, Phaethon fell from the chariot not because he was struck down by Zeus but because of his own terror. The Heliades were then turned into poplar trees as punishment for helping Phaethon.[13]

Finally, there may have been yet another version of the story, known only from ancient art, in which Artemis helped kill Phaethon.[14]

Popular Culture

The myth of Phaethon has remained tremendously popular in Western culture: references to Phaethon can be found in the works of Dante, Shakespeare, and many others. More recently, his myth has been adapted in modern poetry, novels, cinema, and radio. A few celestial bodies have also been named after Phaethon.

Whereas for the ancients, Phaethon generally symbolized hubris and the dangers of infringing on the realm of the gods, modern interpretations are more sympathetic: Phaethon has increasingly come to symbolize mankind’s struggle for power and individualism in a harsh universe.

In Angus Wilson’s novel Setting the World on Fire (1980), for example, a painting of Phaethon inspires the protagonist’s emergent understanding of himself. Meanwhile, one of the characters in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (1957) composes an opera in which Phaethon is ultimately successful in controlling the chariot of the sun.