Phaedra (Play)

Phaedra by Alexandre Cabanel (1880)

Fabre Museum, MontpellierPublic DomainOverview

The Phaedra is a Roman tragedy composed by Seneca during the time of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (first century CE). The play—which to some extent is a reworking of Euripides’ Hippolytus—portrays the grim consequences of Phaedra’s unrequited love for her stepson Hippolytus.

The Phaedra delves into themes of gender, family, guilt, and humans’ relationship with nature. It has been highly influential throughout Western history, inspiring many adaptations, and is still widely read today.

Key Facts

Who wrote the Phaedra?

The Phaedra is attributed to the Roman author Seneca, usually thought to be Seneca the Younger. However, some scholars have made the case that the play was actually authored by Seneca the Elder, the father of Seneca the Younger.

A double herm of Seneca and Socrates (3rd century CE)

Antikensammlung, Berlin / CalidiusCC BY-SA 3.0What is the Phaedra about?

In Seneca’s play, Phaedra tries to seduce her stepson Hippolytus. When Hippolytus spurns her advances, she accuses him of having raped her. This leads to the death of Hippolytus and, eventually, to Phaedra’s own death: she ultimately kills herself out of guilt and shame.

A fresco showing Phaedra with her nurse from the House of Jason in Pompeii (1st century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainTitle

Seneca’s Phaedra takes its title from the central character of the play, the wife of Theseus and the stepmother of the doomed Hippolytus.

The name “Phaedra” is Greek in origin, known from numerous Greek mythical sources (Greek Φαίδρα, translit. Phaídra).

An earlier tragedy titled Phaedra is known to have been produced by the Greek dramatist Sophocles, but this work is now lost. Euripides’ play on the same subject has survived intact, but it was titled Hippolytus rather than Phaedra (after the other central character of the tale).

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Phaedra Φαίδρα Phonetic

IPA

[FEE-druh] /ˈfi drə/

Author

The Phaedra is among the corpus of plays attributed to Seneca. Most modern scholars claim that the Seneca in question is Seneca the Younger (Lucius Annaeus Seneca), who was born between 1 BCE and 4 CE and died in 65 CE.

However, no ancient source explicitly states which Seneca composed these works. Thus, it is possible that the so-called “Senecan Tragedies” were, in fact, composed by Seneca the Elder (also named Lucius Annaeus Seneca), the father of Seneca the Younger. A celebrated writer, Seneca the Elder lived from approximately 54 BCE to 39 CE.

The Senecas came from a Roman equestrian family in Corduba, Spain. Seneca the Elder enjoyed a distinguished career as an orator and writer. He composed a few historical works that have been lost, as well as two rhetorical handbooks, the Controversiae (“Controversial Issues”) and the Suasoriae (“Persuasions”), selections of which do survive.

Seneca the Younger was educated in Rome, where he had a notable public career as the tutor and advisor of Nero, who became emperor in 54 CE. However, he eventually fell out with the tyrannical emperor. After being implicated in the Pisonian Conspiracy against Nero in 65 CE, he was forced to commit suicide.

The Death of Seneca by Manuel Domínguez Sánchez (1871)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainSeneca the Younger was an important orator and philosopher. An adherent of Stoicism—a philosophical school stressing virtue ethics—Seneca produced various philosophical works as well as a collection of Moral Letters. He also wrote a satirical account of the deification of the emperor Claudius, called the Apocolocyntosis (“Pumpkinification”).

Ten tragedies attributed to Seneca have survived, including the Medea, the Phaedra, and the Trojan Women (though two of the ten—Octavia and Hercules on Oeta—are usually thought to have been written by a different author). Interpretations of these tragedies have been heavily influenced by Seneca the Younger’s philosophical leanings, with many scholars finding Stoic themes throughout the plays.

Though little is known about the reception of Senecan tragedy in ancient Rome, the collection became quite important in Renaissance and early modern Europe. Many later European works—including the tragedies of Shakespeare—were heavily influenced by the tradition of Senecan tragedy.

Mythological Context

The story of Phaedra and Hippolytus originated as one of the ancient Greek myths surrounding Theseus, the most famous hero of the city of Athens. The myth is best known from Euripides’ tragedy Hippolytus—probably the main source of inspiration for Seneca’s Phaedra.

Euripides actually wrote two tragedies on the myth of Hippolytus. The first (sometimes known as Hippolytus Veiled—Hippolytos Kalyptomenos in Greek—to distinguish it from the second play) was condemned by contemporaries and is known today only from fragments.

The second Hippolytus play (sometimes known as Hippolytus Crowned, or Hippolytos Stephanephoros in Greek) had much better luck, winning first prize in dramatic competition and surviving intact to the present.

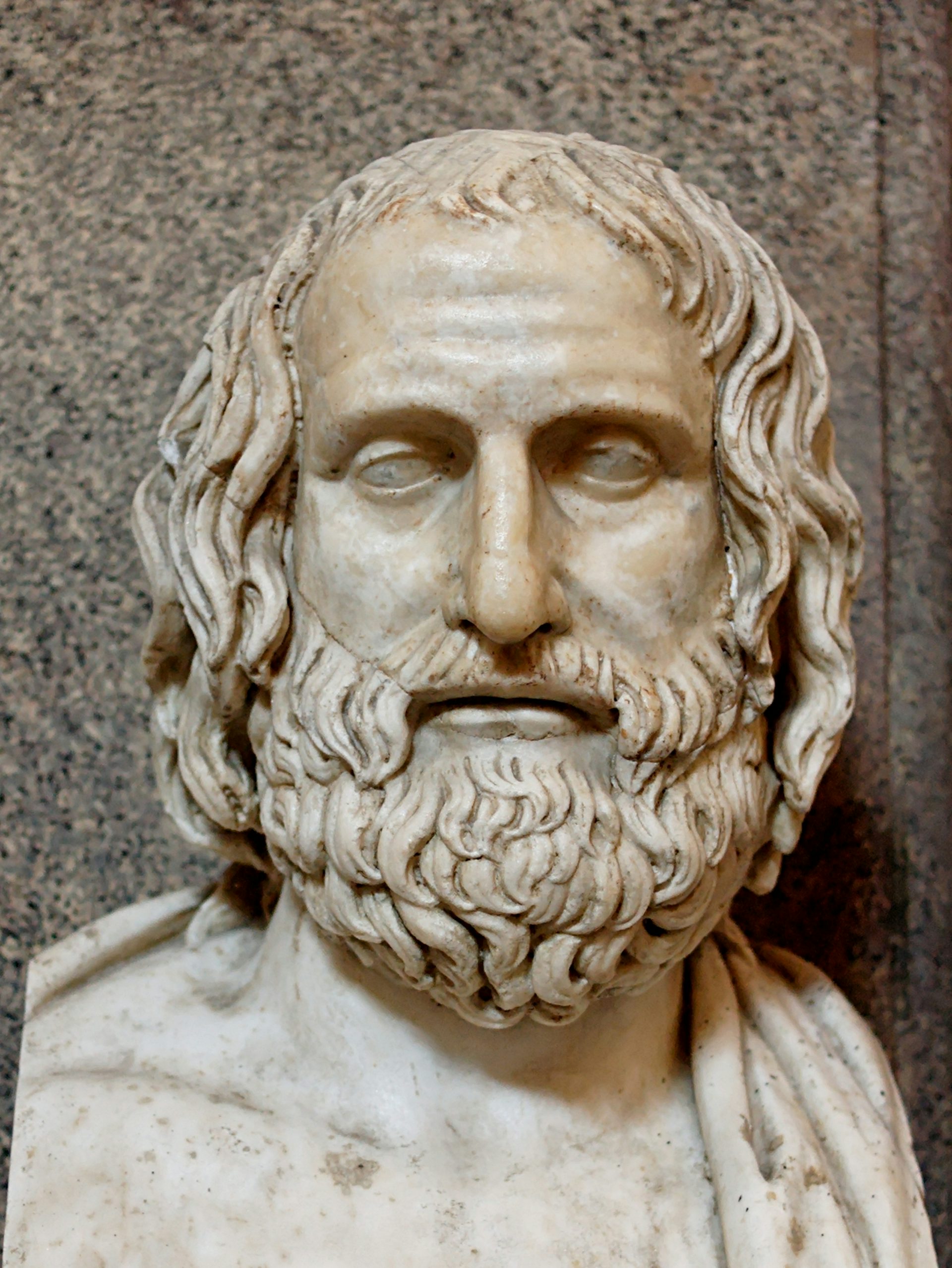

Roman bust of Euripides after a Greek original from ca. 330 BCE

Vatican Museums, Vatican / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainEuripides’ version of the myth of Hippolytus and Phaedra—or at least, the one known from his second surviving Hippolytus—presents Phaedra’s passion for her stepson as a divine punishment from Aphrodite, who is angry at Hippolytus for neglecting her worship by remaining a virgin. The conscientious Phaedra, horrified by her inappropriate feelings, finally confides in her nurse, who promises to help her.

In a key scene, Euripides has Phaedra’s nurse proposition Hippolytus on her mistress’s behalf, but only after making him swear an oath never to repeat her words to anyone. Hippolytus is disgusted by Phaedra’s advances and violently rebuffs her. Despairing, Phaedra kills herself—but not before accusing Hippolytus of raping her.

Theseus, having just returned home from an embassy, learns of Phaedra’s accusation and confronts Hippolytus. Hippolytus does his best to defend himself without breaking the vow of silence he made to the nurse—but to no avail. Theseus ultimately banishes Hippolytus and asks Poseidon to punish him for his supposed crime.

Poseidon, unfortunately, grants Theseus’ prayer, causing Hippolytus’ horses to panic and trample their master as he is leaving Athens. Euripides then has Artemis appear above the stage to reveal the truth to Theseus and rebuke him for his behavior. The dying Hippolytus is brought in, and father and son are reconciled before the end.

Though this quickly became the most recognizable version of the myth of Hippolytus and Phaedra, it was not the only one circulating in antiquity. Euripides’ first Hippolytus, for example, seems to have departed from the second version of the play in several notable ways, including by placing Phaedra’s suicide after the death of Hippolytus, rather than before it.

The Death of Hippolytus by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1715)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainAnother adaptation of the myth was Sophocles’ Phaedra, which is now known only from fragments. Sophocles’ play apparently differed from both of Euripides’ in several ways, including by having Theseus return from the Underworld rather than from an embassy.

Other than these Attic tragedies, the myth of Hippolytus and Phaedra received surprisingly few literary treatments in Greek literature. One fourth-century BCE critic and scholar, Asclepiades of Tragilus, recorded a version of the story in which Phaedra propositions Hippolytus while he is governing Troezen. In this version, as in Euripides’ first Hippolytus, Phaedra kills herself only after Hippolytus’ death.

A little later, the Hellenistic poet Lycophron produced a poem titled Hippolytus, though this work has not survived, and next to nothing is known about it.

Roman literature was familiar with the myth even before Seneca. There are references to Hippolytus or Phaedra in the poems of Virgil and Ovid, for example; particularly important among these works is Ovid’s Heroides 4, a poem presented as a letter from Phaedra to Hippolytus.

Other Roman authors claimed that after Hippolytus’ untimely demise, he was resurrected by the prodigious healer Asclepius and lived the rest of his life in Italy.

Characters

The following is a list of characters from Seneca’s Phaedra, in order of appearance:

Hippolytus (son of Theseus; stepson of Phaedra)

Phaedra (wife of Theseus; stepmother of Hippolytus)

Nurse

Chorus

Theseus (king of Athens; husband of Phaedra; father of Hippolytus)

Messenger

Synopsis

Act 1

The play begins with a long ode sung by Hippolytus, the son of the Athenian king Theseus and an Amazon woman (either Hippolyta or Antiope, depending on the source). A chaste young man, Hippolytus is preparing to go hunting and prays to Diana, the virgin goddess of the wild, for success.

Hippolytus’ stepmother Phaedra, a princess from Crete, enters and stands before the palace. She laments that her husband Theseus has been away for so long on a quest to help his friend Pirithous abduct Proserpina from the Underworld. She speaks of her mother Pasiphae’s unholy passion for her husband’s prize bull, hinting that she, too, is under the sway of a forbidden passion.

A fresco from Pompeii showing Phaedra with an attendant (ca. 20–60 CE)

British Museum, London / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainIt is gradually revealed that Phaedra is in love with her stepson Hippolytus, who shuns all women. Phaedra’s nurse tells her mistress to try and control this dangerous desire. But when Phaedra confesses that she fears she cannot, the nurse promises to help her.

The Chorus enters and sings their first choral ode. They proclaim the power of love and the unrivaled sway of Venus and Cupid—the gods of love—who can overcome even the most powerful deities.

Act 2

Hippolytus enters, having returned from the hunt. The nurse speaks to him first, trying in vain to convince him to relax his commitment to chastity. Hippolytus responds by praising the purity of the natural world and deprecating all women.

Phaedra, meanwhile, falls in a faint. Hippolytus revives her and Phaedra reveals to him, in stages, that she is in love with him. Hippolytus is disgusted and almost kills Phaedra, before changing his mind and fleeing in horror.

Phaedra and Hippolytus by Josef Geirnaert (1819)

Bowes Museum, Barnard CastlePublic DomainThe nurse decides to accuse Hippolytus of raping Phaedra in order to hide her mistress’s crime. The Chorus is troubled by all that has happened and sings the second ode, praising the beauty of Hippolytus, while noting that the beautiful often suffer terrible fates.

Act 3

Theseus comes back from the Underworld and finds Phaedra on the verge of suicide. At her husband’s insistent questioning, Phaedra finally “admits” that Hippolytus raped her, threatening her with his sword. Theseus is furious and prays to his father Neptune, asking him to destroy Hippolytus. This is followed by the Chorus’s third ode, which laments the arbitrary power of fate.

Act 4

A messenger enters and mournfully describes Hippolytus’ death: while Hippolytus was riding his chariot by the shore, a terrifying bull rose from the sea and caused his horses to panic. Hippolytus was thrown from his chariot, became tangled in the reins, and was torn apart. Theseus weeps at the news, experiencing conflicting emotions over the death of his son.

In their fourth ode, the Chorus observes that the gods make the rich and powerful suffer more than the lowly.

The Death of Hippolytus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1860)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAct 5

Phaedra grieves over the body of Hippolytus, finally confessing the truth to Theseus before killing herself. Theseus is devastated by the news, severely reprimanding himself for his son’s death. He tries desperately to reassemble Hippolytus’ dismembered corpse and gives orders for the body to receive an honorable burial.

Style and Composition

Seneca’s Phaedra is an example of what the Romans called a fabula crepidata or fabula cothurnata—a tragedy in Latin, but composed in the Greek style. While Seneca’s tragedies are the only surviving examples of this literary genre, they were hardly the most important or famous representatives in antiquity.

The most highly regarded authors of such tragedies were Ennius (239–169 BCE), Pacuvius (220–ca. 140 BCE), and Accius (170–ca. 90 BCE), all of whom lived long before Seneca. Unfortunately, their works are now known only from fragments.

Ennius, Pacuvius, and Accius all wrote tragedies designed to be performed on the stage, with actors, costumes, scenery, and prompts. Yet by the first century CE—the period in which Seneca’s tragedies were being composed—stage tragedies had gone out of fashion.

Probably the last important tragedy composed for the stage was the Thyestes of L. Varius Rufus, which was first performed in 28 BCE (the play, though regarded as a masterpiece in antiquity, is now lost). Thereafter, tragedies were typically recited in front of smaller (and usually upper-class) audiences.

A Roman mosaic showing the theatrical masks of tragedy and comedy (2nd century CE)

Capitoline Museums, RomePublic DomainSeneca’s tragedies are examples of the type composed for recitation rather than stage performance. Though they bear some similarities to the earlier stage-tragedies—including a taste for gruesome violence—they also depart from the older models in important ways, favoring a more artificial rhetorical style. Indeed, the rhetoric of Seneca’s plays frequently draws attention to itself, with characters often breaking into rhetorical “declamations.”

Senecan tragedy is also full of elaborate metaphors and similes and grandiose language. This has led some critics to view these works as unbalanced creations, forever vacillating between elegance and bombast.

Themes

Seneca’s Phaedra uses stylistic devices such as rhetoric, metaphor, and simile to explore diverse themes, including the destructive potential of passion, humans’ relationship with nature, fate, guilt, and gender.

Many scholars have seen the central theme of the Phaedra as passion’s triumph over reason—a major concern for the Stoics, who privileged virtue and reason above all else. Phaedra serves as the most obvious example of the consequences of failing to control one’s impulses. Yet Hippolytus and Theseus are also ruled by their emotions, and their unruly passions ultimately destroy Theseus’ family.

Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix from Vulci (ca. 440–430 BCE) showing Theseus (left) killing the Minotaur (right)

British Museum, London / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5Natural imagery also pervades the play, including references to the woods, animals, and hunting. Seneca uses this imagery to reflect on humans’ relationship with the natural world and with the passions that govern them (instead of being governed by them).

Each character’s relationship to nature also embodies their personality and worldview. Thus, the innocent and naive Hippolytus equates nature with freedom; the jaded Phaedra views nature as hostile and dangerous; and the tyrannical Theseus views nature as an enemy to be conquered and subjected.

Behind the play’s exploration of passion and its destructiveness is a tension between fate and human responsibility. Phaedra is the first to view her actions as determined by external factors, such as fate, the will of the gods, or even hereditary guilt. Phaedra, like her mother Pasiphae (who begot the Minotaur after sleeping with the Cretan Bull), is plagued by a forbidden love.

Hippolytus, similarly, is viewed as paying for the sins of his father (or even those of his stepmother). And the Chorus often sings of the power of fate and the gods over human affairs.

Opposing this sense of predestination is the notion that human beings are responsible for their own actions. This idea is articulated most clearly by the nurse, but is generally rejected by the other characters—to their great detriment.

Sex and gender roles also occupy an important place in the play. Hippolytus is a fervent misogynist who shuns women and views them as the root of all evil.

But Phaedra also struggles with the expectations of her gender; her desire for Hippolytus in some ways exposes the hypocrisy of ancient gender roles, where men (like Theseus) had free rein to behave as perversely as they pleased, while women (like Phaedra) were expected to remain chaste and submissive.

Phaedra and Hippolytus by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (ca. 1802)

Fogg Museum, Harvard UniversityPublic DomainReception

The myth of Phaedra and Hippolytus was favored by Roman poets and artists of the Imperial period, well into the fourth or fifth century CE. Seneca’s Phaedra, composed during the very early Imperial period, no doubt had a hand in inspiring this popularity.

Marble sarcophagus showing the myth of Hippolytus and Phaedra (ca. 290 CE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainSeneca was also immensely popular in Renaissance Europe. During the fifteenth century, Pomponius Laetus inaugurated a tradition of performing Latin dramas (including Seneca’s) on the stage. Seneca’s Phaedra was produced in 1490, with additional productions emerging in subsequent centuries.

Seneca’s Phaedra spawned many adaptations, including Racine’s famous Phèdre (1677) as well as a shorter poem or mini-drama by Swinburne (1866). Senecan tragedies also inspired English tragedians such as Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe (and Shakespeare, too, though probably to a lesser degree). Even some operas, like Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), owe something to Seneca’s play.

Today, the Phaedra is one of the most widely read Senecan tragedies. It is still sometimes performed on stage.

Translations

Translations of Seneca’s Phaedra usually appear alongside other Senecan tragedies. The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Miller, Frank Justus, ed. and trans. Seneca: Tragedies, Vol. 1: Hercules Furens, Troades, Medea, Hippolytus, Oedipus. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917: Older prose translation with facing Latin text (Phaedra is translated under the title Hippolytus). Though it has been replaced in the Loeb Classical Library with a newer translation, it can still be found online.

Ahl, Frederick, trans. Seneca: Phaedra. Masters of Latin Literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986: Verse translation with a useful introduction and notes.

Boyle, Anthony James, ed. and trans. Seneca’s Phaedra. Liverpool: Francis Cairns, 1987: English translation with facing Latin text; includes a commentary.

Wilson, Emily, trans. Seneca: Six Tragedies. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010: Well-regarded verse translation with linked explanatory notes.

Fitch, John G., ed. and trans. Seneca: Tragedies, Vol. 1: Hercules, Trojan Women, Phoenician Women, Medea, Phaedra. Rev. ed. Loeb Classical Library 62. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018: Accurate prose translation with facing Latin text.