Parvati

Overview

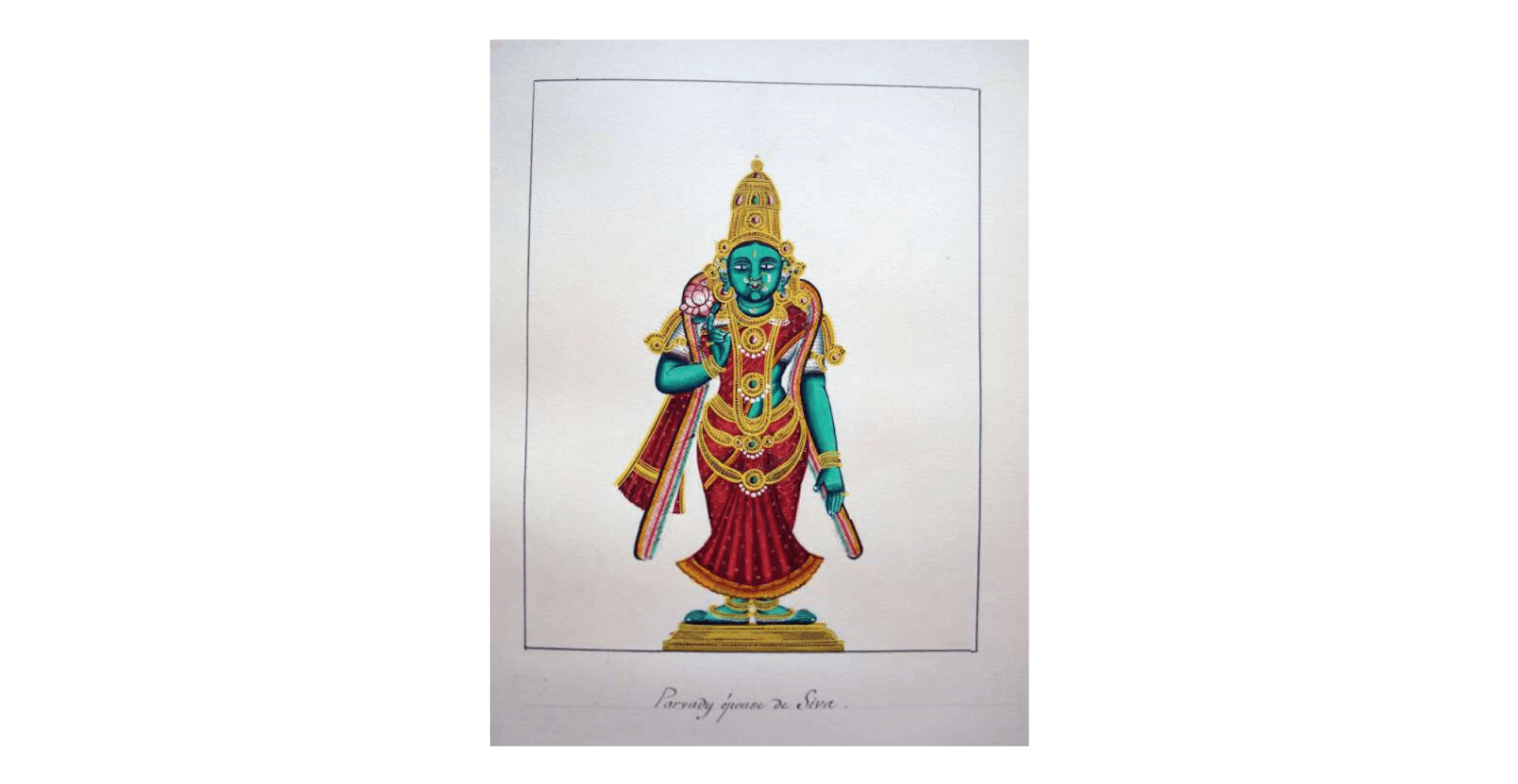

Painting of Parvati with green skin, arrayed in jewelry and holding a lotus. Tamil Nadu, ca 1850. British Museum, London.

Trustees of the British MuseumPublic DomainCompared to other goddesses of Indian mythology, Parvati is set apart for two reasons.

Firstly, she is known for practicing extreme asceticism, a set of practices normally reserved for men in ancient Indian society. These practices include leaving home, living on only one meal a day, meditating for hours, holding one arm above one’s head for years at a time, making four fires and sitting between them during the hottest part of the day, dressing in tree bark, and so on. In this way, she mirrors her husband Shiva, also known as an ascetic god.

She is also important due to her identification with a number of different goddesses—both warlike and wrathful goddesses such as Kali and Durga and more peaceful goddesses such as Ambika, Sati, and Annapurna. Worshippers see her as either a manifestation of one of these goddesses or as the ultimate source of them.

Aside from her asceticism and association with mountainous areas, Parvati is worshipped as a goddess of hearth and home, marriage, and family. But she is by no means a passive goddess. According to one tale in the Shiva Purana, she grew so angry at the death of her child Ganesha that she summoned an army of celestial warrior goddesses and assaulted the heavens. She was only calmed once Ganesha was brought back to life.

Parvati also actively pursues her own goals; for example, she undertook her extreme asceticism in order to impress Shiva and convince him to marry her. Even after this plan succeeded, Parvati had to persuade him to be properly married in accordance with orthdox Hindu Brahmanical rites. Later, Parvati insisted on having a child despite Shiva’s reluctance and mockery.

Having “tamed” the wild god Shiva, who usually keeps a safe distance from normal society, she has become the embodiment of domestic home life. The fact that both Parvati and Shiva enthusiastically practice austerities in the mountains—the antithesis of the orthodox Hindu householder ideal—makes them a complicated couple.

Etymology

The etymology of Parvati’s name is straightforward: it derives from the Sanskrit parvata, meaning “mountain” or “mountainous.” Pārvatī is an adjectival form of parvata, denoting her descent from her father, the personification of the Himalayan Mountains, whose names include “Himavan” and “Himavat” (also meaning “mountain”). In this sense, “Parvati” means either “Mountainous One” or “Daughter of the Mountain.”

Pronunciation

English

Sanskrit

Parvati or Pārvatī पार्वती Phonetic

IPA

[PAR-vuh-tEE] / paːrʋɐtiː /

Alternate Names

Parvati has a fluid relationship with a number of other goddesses found in Hindu literature and mythology. She is often characterized as the source of, or the same being as, the following goddesses:

Sati (सती), “Virtuous”

Durga (दुर्गा), “Impassable” or “Tough Going”

Kali (काली), “Black” or “Time”

Annapurna (अन्नपूर्णा), “Full of Food”

Ambika (अम्बिका), “Mother”

Titles and Epithets

Many of Parvati’s epithets reflect her strong association with mountains:

Shailasuta (शैलसुता), “Daughter of the Mountain”

Gauri (गौरी), “Golden”

Giriputri (गिरिपुत्री), “Daughter of the Mountain”

Girirajaputri (गिरिराजपुत्री), “Daughter of the Mountain King”

Girisha (गिरीशा), “Mistress of the Mountain”

Uma (उमा), “Mother”

Shakti (शक्ति), “(Feminine) Power”

Attributes

Parvati is often depicted holding such objects as a lotus, vase, rosary, mirror, or trident. She is sometimes shown gesturing, an indication that she is granting boons.

Domains

Because of the lengths Parvati went to in order to marry Shiva, she is known as a goddess of fertility, love, marriage, and the householder ideal in general—a foil to her starkly ascetic husband. Yet the extreme austerities she practices high in the Himalayas also make her a symbol of asceticism and shakti (feminine power).

Family

Due to Parvati’s status as a symbol of both domesticity and shakti, family is essential to her mythology. Her most important relationships are with her husband, Shiva, the god of destruction, and her sons Ganesha and Karttikeya, gods of removing obstacles and war, respectively.

Parents

Fathers

Mother

- Himavati

- Daksha

- Mena

Siblings

Sisters

- Ragini

- Kutila

Consorts

Husband

Children

Sons

- Skanda Karttikeya

- Ganesha

- Andhaka

Mythology

Origins

Earliest Evidence

While Parvati does not appear in Vedic literature, literary and numismatic sources from the first few centuries BCE and CE reference a figure that possibly served as her prototype. In the Kena Upanishad (3.12) we read:

sa tasminnevākāśe striyamājagāma bahuśobhamānāmumāṃhaimavatīṃ tāṃhovāca kimetadyakṣamiti

At that very spot [Indra] came upon a woman, Uma, Daughter of Himavati, radiant in appearance, and said to her, “What spirit is this?”

This passage establishes that a figure named “Uma,” who was also the daughter of the mountain, was already in circulation in the later centuries BCE, although it is uncertain whether she can be identified as the same figure who would later become Parvati or Sati-Parvati.

More reliable dating comes from the coinage of the Kushana king Huvishka (ca. 150 CE). One gold coin in particular shows an image of Huvishka on the obverse and an image of two gods on the reverse. The figures are labeled as ΟΟΜΑ (“Ooma”) and ΟΗÞΟ (“Wesho”) in Baktrian, a Central Asian-Iranian language that used a modified form of the Greek alphabet. The Baktrian spelling corresponds to Uma, a name for Parvati, while “Wesho” is sometimes identified with Shiva or Herakles.

Gold coin of King Huvishka with Uma (Parvati) and Wesho (possibly Shiva) on the reverse. Minted in western India, ca. 150 CE. British Museum, London.

Trustees of the British MuseumPublic DomainOrigins of Goddesses in Hinduism

Several scholars have postulated that Parvati originated from pre-Aryan goddesses of the Indian subcontinent, who gradually merged and were adopted into Vedic and Brahmanical traditions. According to David Kinsley,

It is quite possible that Pārvatī’s early history and origin may lie with a goddess who dwelled in the mountainous regions and was associated with non-Āryan tribal peoples … Such a goddess would be an appropriate mate for Śiva, himself a deity who dwells in mountainous regions and on the fringes of society.[2]

The origin of Hindu goddesses in general is a concern for Cornelia Dimmit and J. A. B. van Buitenen, who note the almost complete lack of goddesses in Vedic literature. They agree that their origin, along with many traits of Vishnu and Shiva found in the Hindu Puranic texts, can be traced to non-Aryan Indian peoples that coexisted with the early Aryan invaders who made up the upper classes:

Almost every goddess in the Purāṇas is married to a god, with the exception of the fierce and war-like Durgā and Kālī. Perhaps the marriage of gods and goddesses in Hindu mythology reflects a synthesis that in fact occurred between two different races and cultures in the early history of Indian culture.[3]

Wendy Doniger expands on this idea and postulates a two-stage development for Hindu goddesses:

first the Indo-Aryan male gods were given wives, and then, under the influence of Tantric and Śāktic movements which had been gaining momentum outside orthodox Hinduism for many centuries, these shadowy female figures emerged as supreme powers in their own right, and merged into the great Goddess.[4]

The “great Goddess” here refers to Mahadevi, an all-powerful and creative goddess according to Shakti traditions in Hinduism. She is the ultimate source for all other goddesses, gods, the Vedas, and the entire universe. Shaiva traditions claim that Mahadevi is none other than Parvati herself.

Former Life as Sati

Before her life as Parvati, she lived as the goddess Sati, daughter of Daksha, who was the son of the god Brahma. By all accounts, she was the embodiment of the Hindu ideal of a virtuous wife.

When her father insulted both Sati and Shiva by not inviting them to a ceremony, Sati grew so incensed that she killed herself by walking into a fire. According to the Devibhagavata Purana, “Because of this offence, Satī burnt that body, which [Daksha] had begotten, in the fire of her yoga, with a desire to demonstrate the dharma of ‘suttee.’”[5] The goddess Sati eventually gave her name to the now-abandoned Hindu practice of widows committing suicide by throwing themselves onto the funeral pyres of their husbands.

David Kinsley sees Sati as a mediating figure. On one side stands the worldly, established, orthodox religious life, characterized by the householder ideal. On the other stands the ascetic lifestyle in which one remains celibate and homeless, wandering from town to town and living without a family. By marrying Shiva, Sati bridged these two poles. “When she kills herself,” Kinsley writes, “she precipitates a clash between these two worlds, between Dakṣa and Śiva, which is initially destructive but ultimately beneficial and creative.”[6]

When Shiva learned of Parvati’s death, he was so distraught that he carried her charred remains over his shoulder. In the process, fifty-one pieces of her body fell to the earth and became religious sites. Her yoni (vagina) fell to the earth last, and Shiva came down to earth in the form of a linga (phallus) so that he could stay with her forever.

Pursuit of Shiva

In one tale, Parvati was born with two sisters, and all three desired Shiva for a husband. At the time, the entire cosmos was threatened by a terrible demon (as was often the case), this time in the form of the buffalo demon Mahisha. His fierce power came from a blessing which said that he could only be killed by Shiva’s shakti, or immense feminine power.

All three sisters began practicing asceticism at the age of six, and their efforts so impressed the gods that they suspected one of the girls might eventually slay Mahisha. The gods took the eldest daughter, Ragini, to heaven and asked the creator god Brahma if she was the one. But Brahma was unimpressed and transformed her into a raging river that flooded Brahma’s heaven. The gods tested the second daughter, Kutila, but she too was unworthy. And so Brahma transformed her into the twilight.

After losing her first two daughters, their mother Mena told Parvati, “O, don’t!”[7] to stop her from practicing austerities and meeting the same fate as her sisters. But it was too late: Parvati sat in the mountains, “her mind fixed on the god who holds the trident, whose banner bears the bull,” and “having united with Rudra (Shiva) in her heart, she continued to practice intense tapas.”[8]

When the gods came to take Parvati to heaven, her brilliance so astounded them that they stood in awe of her radiance and could not approach her. Brahma announced that Mahisha was as good as slain already, for Parvati was the one.

Some time later, Shiva came to Parvati’s father’s house to rest. He immediately recognized his former wife Sati reborn and set out to test her resolve. When she went to the mountains to perform austerities and worship Shiva, he disguised himself as a hermit and taunted her, saying that her soft hands and rich clothes made her unsuitable to marry a god who wanders clad in ashes and animal skins. He even hurled insults against Shiva (himself) to see how she would react.

But Parvati refused to entertain the strange, wandering hermit any further. Anyone insulting Shiva deserved to be killed, she said, and anyone listening to such a person was bound to suffer as well. Since she could not be swayed from her desire, he dropped the illusion and grabbed her as she turned to leave, saying:

If you leave me, where will you go? O Śivā,[9] I will not leave you alone. I have tested you, blameless woman, and find you firmly devoted to me. … Because of your tapas, I shall be your servant from this moment on. Due to your loveliness, each instant without you lasts an Age. Cast off your modesty! Become my wife forevermore!

The two then flew away to Mount Kailasha. In time, she did her part to defend the cosmos by slaying the buffalo demon Mahisha.

Another version of the story explains that Parvati’s desire to marry Shiva was tied to her desire to defeat the demon Taraka. The demon had performed austerities and impressed Brahma, who granted him a blessing that only the child of Shiva could slay him. Naturally, Taraka understood this to mean that he was invincible, for Shiva was the archetype of the unmarried ascetic, unlikely ever to have children. Knowing this, the gods impressed upon Parvati the need for Shiva to bear a child and sent her to seduce him. In time she was successful, and their war-god son Skanda went on to slay the demon.

Marriage with Shiva

After winning Shiva’s hand, Parvati explained that their previous marriage (when she was Sati) had not been performed correctly—her father had not worshipped the planets properly—and so their lives had fallen into disarray. This time, she declared, they were to have a proper marriage:

Hence, o lord, you will celebrate marriage in accordance with the rules for the fulfilment of the task of the gods. The customary procedures of the marriage shall certainly be followed. Let Himavat know that an auspicious penance has been performed well by his daughter.[10]

At first, Parvati’s parents were unsure whether to agree to their marriage. After all, Shiva had no family, no mother and father, and no great fortune to speak of. He lived as a hermit in the Himalayas, smeared himself with ashes, and spent time in graveyards and cremation grounds. Parvati’s mother, Mena, said bluntly to her husband:

O lord of mountains, I shall not give my daughter endowed with all good accomplishments to Śiva with ugly features, ignoble conduct and defiled name … I would rather drown myself in the great ocean. I shall never give my daughter to him.[11]

It was only through the intervention of seven sages sent by Shiva that they changed their hearts. The sages praised the god and spoke of all his good qualities. Most of all, they reminded Himavan and Mena that Parvati was destined to bear the son who would slay Mahisha and Taraka, and that the planets would soon be in the proper alignment to ensure a healthy child.[12]

According to Parvati’s wishes, they were married in a traditional Brahmanical Hindu ceremony, with all the gods, gandharvas, and apsaras[13] in attendance as the couple circled the sacrificial fire.

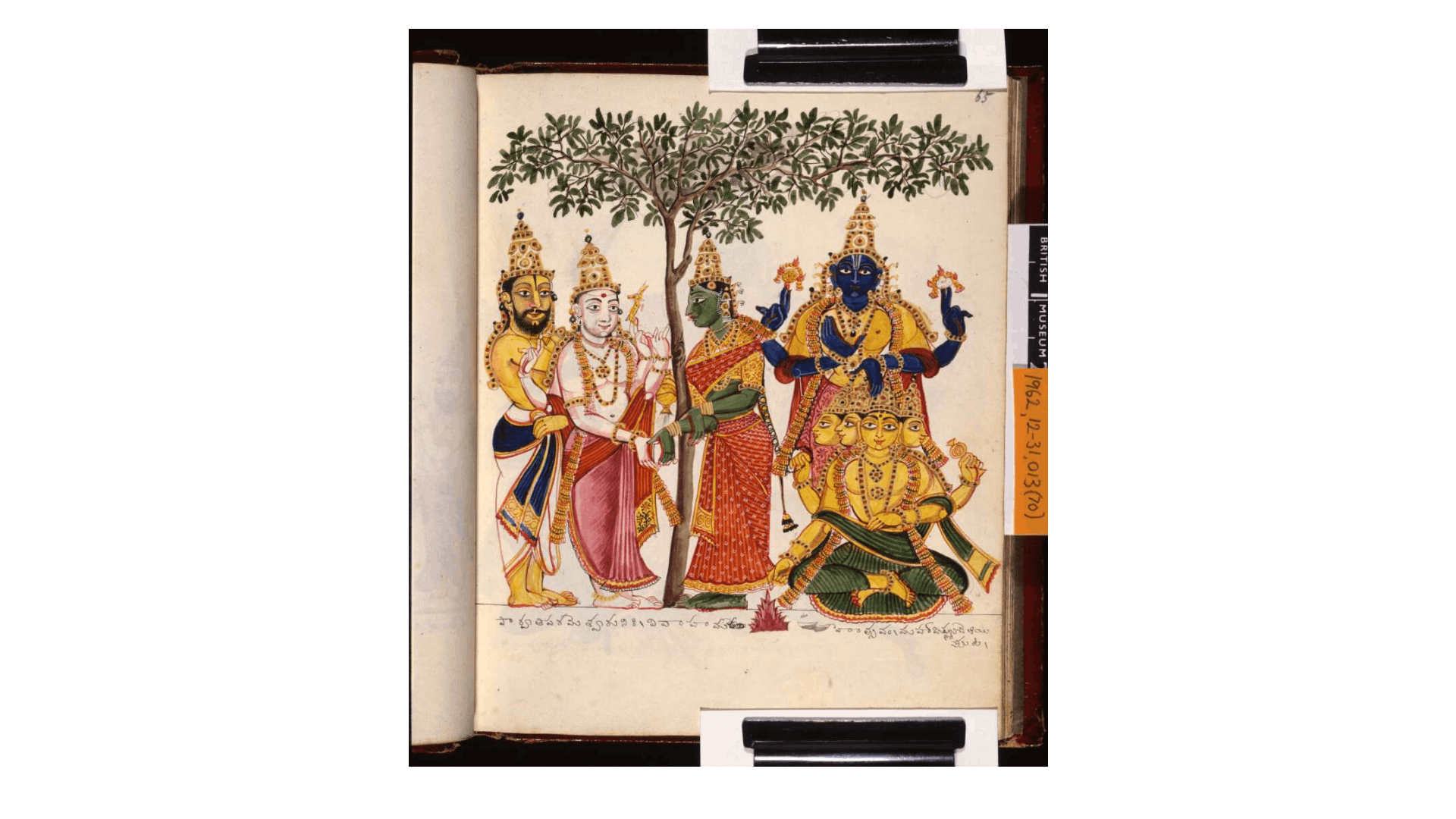

Watercolor painting of the marriage of Parvati and Shiva. Vishnu watches while the four-headed god Brahma performs a fire sacrifice and Parvati's father, Himavan, pours water over the couple's hands to seal their wedding, ca. 1830. British Museum. London.

Trustees of the British MuseumPublic DomainParvati’s Skin Color

A number of episodes with Parvati and Shiva involve everyday relationship problems that escalate to mythological proportions. Shiva once playfully jabbed at Parvati that while his skin was white as a crescent moon, hers was as dark as a blue lotus, and he compared the two of them to a black snake wrapped around a white sandalwood tree.[14] Presumably still joking, he declared, “You offend my sight.”

Parvati did not take kindly to this and replied that he was quick enough to overlook his own faults and project them onto her. Since one of Shiva’s nicknames is “Mahakala,” meaning “Great Death” or “Great Black One,” it was hypocritical for Shiva to call her “Kali” (meaning “Black”). She left in a fury and swore to practice asceticism in the mountains until her skin turned golden.

When Shiva’s attempts to de-escalate their fight failed, he lamented, “Truly, the daughter is like her father in all her ways … Your heart is as hard to fathom as a cavern of Himālaya … and you are as difficult to enjoy carnally as snow.”[15]

Parvati created a massive lion from the powerful, angry curses that she swore at her husband. In time, her ascetic practices caught the attention of Brahma, who offered her a blessing. Parvati asked for a golden body so that her husband would stop calling her dark-skinned. Brahma agreed, and a dark-skinned goddess appeared from her body, leaving a golden counterpart behind. The lion became the new goddess’s mount, and she became known as Kaushiki, meaning “Sheath,” because she had once formed Parvati’s outer layer.

Parvati then returned to her husband to display her new golden skin.

Phyllite statue of Gauri-Parvati with four arms. Ganesha arises from a lotus held in her surviving left hand. Pala dynasty, ca. tenth century CE.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Birth of Ganesha

Parvati is the mother of Ganesha, the elephant-headed god. More details about her relationship with Ganesha can be found in his origin story and in Shiva’s mythology.

Parvati and Kali

According to one story, Kali was born in the middle of a furious battle between demons and the goddess Parvati. The demon army, led by the asuras[16] Chanda and Munda, arrayed itself with its footmen, horsemen, chariots, and elephants and charged straight at the goddess. Parvati grew so enraged at their attempts to kill her that her face grew black as ink. Then suddenly:

there issued forth from between her eyebrows Kālī, with protruding fangs, carrying a sword and a noose, with a mottled, skull-topped staff, adorned with a necklace of human skulls, covered with a tiger-skin, gruesome with shriveled flesh. Her mouth gaping wide, her lolling tongue terrifying, her eyes red and sunken, she filled the whole of space with her howling.[17]

After springing out of Parvati’s face, Kali went on to slay the demon army, down to the very last chariot.

Parvati and Durga

Parvati and Durga are often identified as the same figure in different forms. Stories vary regarding Durga’s origins; the Vishnu Purana claims that she arose from Vishnu himself as “the power that makes him sleep or as his magical, creative power.”[18]

The Skanda Purana says that a powerful demon once threatened the entire cosmos. To defeat him, Shiva asked for help from Parvati, who took on a more violent and warlike form. After slaying the demon, she became known as “Durga,” meaning “inaccessible, danger, distress.”[19]

Another tale from the same text says that a buffalo demon once tried to marry Parvati as she was practicing meditation in the mountains to win over Shiva. When the demon refused to take no for an answer, she became the goddess Durga and slew the demon.

Other tales say that Durga arose from the discarded flesh that Parvati left after shedding her skin. The Vamana Purana, however, claims that the discarded skin developed not into Durga but into the goddess Kaushiki, who then created the goddess Kali.

Parvati and Shakti

Regarding Parvati and her relationship with the concept of shakti, David Kinsley notes:

The idea that the great male gods all possess an inherent power by which or through which they undertake creative activity is assumed in medieval Hindu mythology. When this power, or śakti, is personified it is always in the form of a goddess. Parvati, quite naturally, assumes the identity of Shiva’s śakti in many myths and in some philosophical systems.[20]

As shakti represents the active power of a male god, Parvati assumes an active role in her relationship with Shiva, whether by pursuing him for marriage or convincing him to have children. She urges the otherwise indifferent and detached Shiva towards creation and procreation. Without her, Shiva is inert.

Their relationship is also expressed in a more philosophical sense, with Shiva representing purusha, “person” or “spirit,” and Parvati representing prakriti, or “nature.” The latter, like shakti, is the active force that compels the otherwise passive purusha. Kinsley explains this complex shakti relationship by emphasizing their complementary natures:

Just as in the mythology Pārvatī is necessary for involving Śiva in creation, so as his śakti she is necessary for his self-expression in creation. It is only in association with her that Śiva is able to realize or manifest his full potential. … In short, the two are actually one—different aspects of ultimate reality—and as such are complementary, not antagonistic.[21]

Painting of Parvati playing music to attract Shiva's attention. Shiva sits on his tiger-skin rug next to his mount, Nandi, so enraged at having his meditation interrupted that his hair stands on end. Guler, Himachal Pradesh, nineteenth century.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainParvati and Shiva as Ardhanarishvara

The complex and complementary relationship of Shiva and Parvati is personified in the figure of Ardhanarishvara, literally “the half-woman lord” or “the lord who is half woman.” This divine character is split down the middle, with Shiva usually forming the right half and Parvati forming the left. As A. L. Basham writes,

An interesting iconographical development is that of the Ardhanārīśvara, a figure half Śiva and half Pārvatī, representing the union of the god with his śakti. As Śiva is worshipped in the liṅga or phallic emblem, so Durgā is worshipped in the female emblem, or yoni.[22]

The tale of Sati’s body parts falling to earth, only to have Shiva dismember himself so that his linga would rest forever with her fallen yoni (see above), reinforces their identity as the union of male and female.

Worship

Festivals and/or Holidays

The Gauri Habba (or Gowri Habba) festival comes just before Ganesha Chaturti, a major holiday for Parvati’s son Ganesha. According to tradition, the goddess comes down from Mount Kailasha to visit her parents’ house, and Ganesha comes the next day to bring her back home. The festivities are centered around women; activities include creating small idols of Parvati out of turmeric, decorating clay idols, and giving packets of small gifts to married women.

The festival of Navaratri, or “Nine Nights,” sets aside a night of devotion and celebration for each of Parvati’s (or Durga’s, depending on the tradition) nine avatars, forms, or manifestations. Observations of the festival vary from region to region in India, with some areas feasting on some days and fasting on others. The particular gods or goddesses to be celebrated vary as well, with Durga having greater pride of place in eastern India.

Temples

Being so closely associated with Shiva, images of Parvati often appear in Shiva temples. But Parvati—whether as Parvati herself, as Sati, or as one of her associated goddesses—is the central figure in many temples.

In her former life as Sati, she ended her own life after her father insulted Shiva. Shiva was so distraught at her death that he carried her on his shoulder and danced in his grief, causing fifty-one pieces of her body to fall to earth. Each site where a body part fell became a holy place, known as a shakti pitha, or a “seat of shakti.”

The temple at Kamakhya in Assam is one such shakti pitha, marking the spot where Sati’s yoni fell. Another is Kalighat Temple in Kolkata, marking the place where one of Sati’s toes fell.

Pop Culture

Parvati remains a popular goddess throughout South and Southeast Asia and is widely worshipped in both Shaiva and Shakti traditions of Hinduism. As the mother of Ganesha and the wife of Shiva, the great destroyer god, Parvati can be found wherever Shiva and Ganesha are worshipped.