Orpheus

Orpheus by George de Forest Brush (1890).

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainOverview

Orpheus, the “father of songs,” was a musician and hero of Greek mythology. He was the son of the Thracian mortal Oeagrus (or of the god Apollo) and one of the nine Muses.

Orpheus was a larger-than-life musician: his songs had the ability to move animals, rocks, and trees, and Orpheus himself was regarded not only as a musical innovator but also an important religious figure. In one of his exploits, Orpheus sailed with the Argonauts, whom he saved from the Sirens by drowning out their lethal song with his own.

The main myth of Orpheus involved his love of Eurydice, who died right after she and Orpheus were married. Orpheus descended to the Underworld to rescue her from death but ultimately failed to bring her back. After returning to the land of the living alone, he serenaded the world with his tragic song until he was finally killed by a band of Thracian women or maenads.

Who were Orpheus’ parents?

Orpheus’ father was either a Thracian man named Oeagrus or, in an alternative genealogy, the god Apollo, who was closely associated with art, music, and inspiration. His mother was usually said to have been one of the nine Muses.

Augustan fresco showing Apollo with a kithara from the House of the Scalae Caci on the Palatine Hill in Rome

Palatine Museum, Rome / Dody escouade deltaPublic DomainWhat were Orpheus’ attributes?

Orpheus was imagined as a handsome young man clothed in elaborate Thracian garb. His most important attribute was no doubt his lyre, which he played with unparalleled skill. Sometimes Orpheus was represented in natural scenes, surrounded by wild animals that his music had tamed.

Nymphs Listening to the Songs of Orpheus by Charles François Jalabert (1853)

The Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainHow did Orpheus die?

In the best-known tradition, Orpheus wandered the world aimlessly after he lost his beloved Eurydice, playing his haunting and beautiful music wherever he went.

He was eventually torn apart by the women of Thrace or by the maenads—crazed female worshippers of Dionysus (according to one source, he angered the women by neglecting their company, having decided to mourn Eurydice for the rest of his days).

Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus on his Lyre by Gustave Moreau (1865)

Musée d'Orsay, ParisPublic DomainOrpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus fell deeply in love with a nymph named Eurydice. But on the day of their wedding, Eurydice was bitten by a venomous snake and died.

Heartbroken, Orpheus descended to the Underworld to restore his beloved Eurydice to the land of the living, but he ultimately failed in his quest. In this famous myth, Hades told Orpheus that he could have Eurydice back, but only if he did not turn around as she followed him out of the Underworld. Unfortunately, Orpheus did look back, and Eurydice was lost forever.

Orpheus and Eurydice, attributed to Filippo Pedrini (18th or 19th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEtymology

Different etymologies for Orpheus’ name have been proposed since antiquity. An old folk etymology, recorded by the Roman mythographer Fulgentius, derives the name from the Greek oraio-phōnē, meaning “best voice.”[1]

Modern scholars have suggested that the name “Orpheus” is related to the Indo-European *orbho- or *h₃órbʰos, meaning “orphan” or, more metaphorically, “bereft, abandoned.”[2] The -eus at the end of the name is a suffix attested in some Greek names as early as the Bronze Age and indicates something like “one who has to do with.”[3] Thus, Orpheus’ name roughly translates to “he who has something to do with being orphaned/bereft”—likely a reflection of the loss of his beloved Eurydice.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Orpheus Ὀρφεύς Phonetic

IPA

[AWR-fee-uhs, -fyoos] /ˈɔr fi əs, -fyus/

Titles and Epithets

One of the first epithets to be connected with Orpheus was onomaklyton, “famous of name.”[4] In the fifth century BCE, the poet Pindar referred to Orpheus as aoidan patēr, “father of songs,” and euainētos, “well-praised.”[5] Orpheus also had other epithets, including chrysolyrēs, “of the golden lyre,” and paian, “healer.”

Attributes and Iconography

Orpheus’ most important attribute was his musical prowess, which far transcended normal human abilities. His music was said to have had power over all things, animate and inanimate alike:

While with his songs, Orpheus, the bard of Thrace,

allured the trees, the savage animals,

and even the insensate rocks, to follow him...[6]

Orpheus was regarded as a great musical innovator, the inventor of epic, lyric, and other forms of poetry and song. He was also sometimes credited as the inventor of other important arts, including medicine,[7] writing,[8] and agriculture.[9]

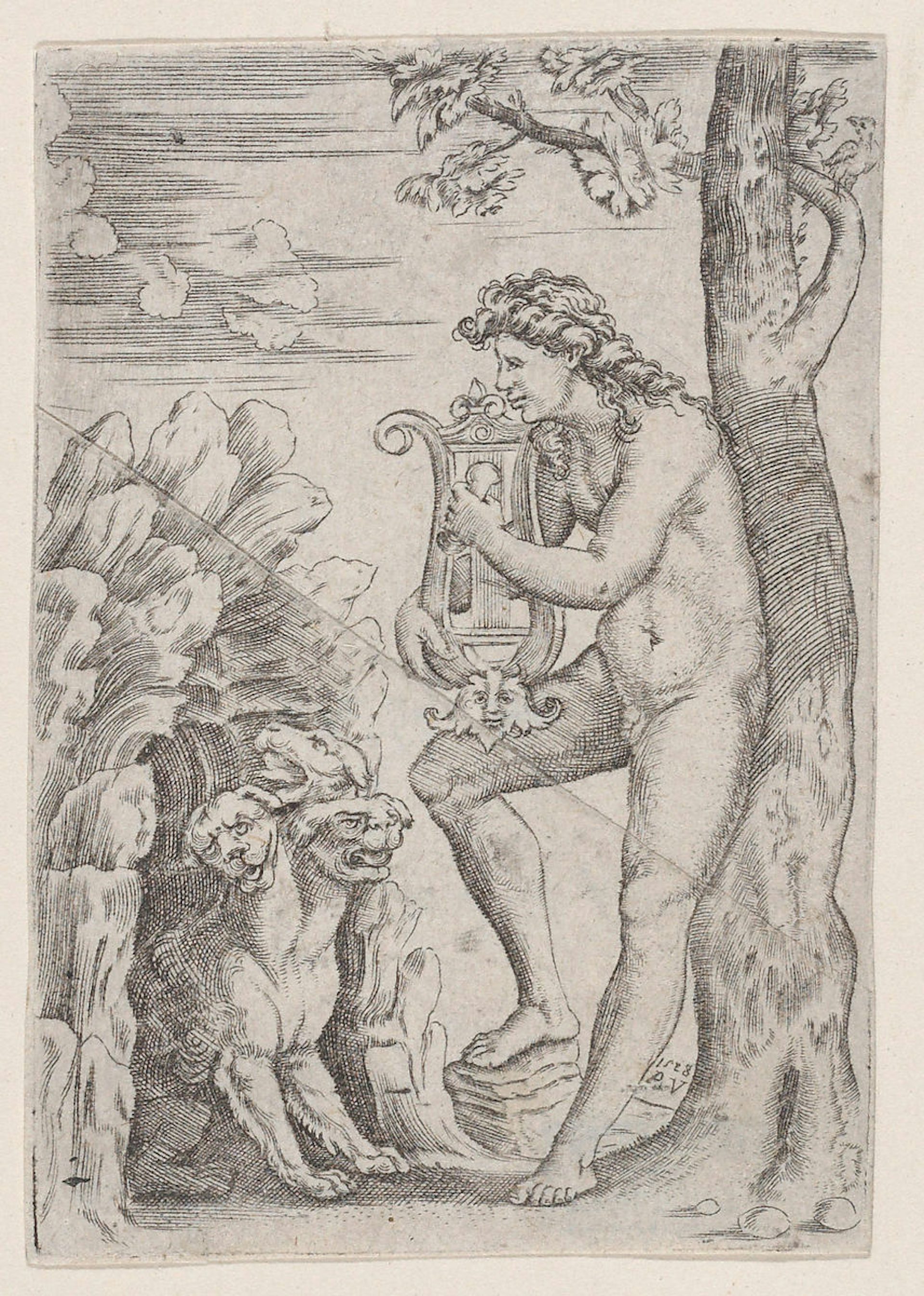

Orpheus by Agostino Veneziano (1528).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainFinally, Orpheus was also a religious and prophetic figure closely associated with Dionysus, the god of wine and madness. He was the mythological inventor of initiation rites in general. More specifically, however, he was the founder of the mysterious Orphic Mysteries, and many ancient religious poems (such as the Orphic Hymns and the Orphic Argonautica) were attributed to him.[10]

Orpheus was a popular figure in ancient art, where he was usually represented as a boyish young man with a lyre, often surrounded by the wild animals and forces of nature that his music was supposedly able to tame.[11]

Family

Orpheus was usually said to have been the son of the Muse Calliope and a mortal man named Oeagrus.[12] But some sources made Orpheus’ father the god Apollo,[13] while others made his mother the Muse Polymnia,[14] the Naiad Menippe,[15] or one of the nine daughters of Pierus.[16]

In some traditions, Orpheus’ brother was Linus, another mythological poet. Linus made the mistake of trying to teach music to the impatient Heracles, who killed him one day in a fit of rage.[17]

In most sources, Orpheus’ love interest (and, for less than a day, his wife) is called Eurydice,[18] though one source names her as Agriope.[19]

According to Diodorus of Sicily, Orpheus was the father of the prophet and philosopher Musaeus, who was associated with the religious mysteries of Attica.[20]

Mythology

Origins

In most traditions, Orpheus came from the wintery region of Thrace, located to the northeast of mainland Greece. But other traditions placed his hometown in northern Greece—for example, in the town of Bisaltia[21] or in Pimpleia (located in the foothills of Mount Olympus, the home of the Greek gods).[22]

As a young man, Orpheus quickly proved himself an inordinately gifted musician (hardly a surprise for the son of a Muse). He was sometimes said to have received the lyre as a gift from Apollo himself, and to have improved on the instrument by increasing the number of strings to nine (in honor of the nine Muses).[23] Orpheus traveled the world, learning about the gods and spreading knowledge about their worship.[24] According to some sources, he voyaged as far as Egypt.[25]

The Voyage of the Argonauts

According to one popular tradition, Orpheus sailed with the Argonauts, a band of Greek heroes who accompanied Jason in his quest for the Golden Fleece.[26] Orpheus proved a great help to the other heroes, providing them with musical accompaniment to guide their rowing as well as entertainment.

When the Argonauts needed to sail by the Sirens, sea monsters who lured sailors to their death with their enchanting song, Orpheus played his lyre so beautifully that he drowned out the Sirens and saved the crew.

Orpheus and Eurydice

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, though quite ancient, is best known through the works of the relatively later Roman poets Virgil and Ovid (around the end of the first century BCE and the beginning of the first century CE).[27]

According to Virgil and Ovid (and a handful of others), Orpheus and Eurydice fell in love and were married. But on their wedding day, Eurydice was bitten by a venomous snake and died (at the time, she was either fleeing from an unwanted suitor or dancing with the nymphs).

Understandably heartbroken, Orpheus resolved to bring Eurydice back from the Underworld. Armed only with his lyre, he was one of the few mortals in Greek mythology to ever pass through the Underworld alive; the shocking beauty of his music stilled even Cerberus, the terrifying three-headed guard dog of Hades.

Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1861).

Museum of Fine Arts, HoustonPublic DomainOrpheus’ journey and his music so moved Hades and Persephone, the king and queen of the Underworld, that they permitted Orpheus to take Eurydice back with him to the land of the living—but only if Orpheus did not turn around while leading her up. As Orpheus was leaving the Underworld, he began to worry that Hades had deceived him. To reassure himself, he peeked behind his shoulder, only to see Eurydice snatched away forever because he had disobeyed the gods of the Underworld:

And now with homeward footstep he had passed

All perils scathless, and, at length restored,

Eurydice to realms of upper air

Had well-nigh won, behind him following—

So Proserpine had ruled it—when his heart

A sudden mad desire surprised and seized—

Meet fault to be forgiven, might Hell forgive.

For at the very threshold of the day,

Heedless, alas! and vanquished of resolve,

He stopped, turned, looked upon Eurydice

His own once more. But even with the look,

Poured out was all his labour, broken the bond

Of that fell tyrant, and a crash was heard

Three times like thunder in the meres of hell.[28]

There appear to have been different versions of this myth. In one, retold by the philosopher Plato, the gods actually did trick Orpheus when he descended to the Underworld to bring back his wife. Instead of giving him the real Eurydice, the gods presented Orpheus with a phantom—a punishment, says Plato, for Orpheus' cowardice in being unwilling to die for his wife.[29]

Death

There is no standard version of how Orpheus died. In most traditions, he was unable to stop mourning the loss of his wife. Thus, he wandered the world playing sad melodies on his lyre until he was eventually torn apart by a band of Thracian women or Dionysian maenads.

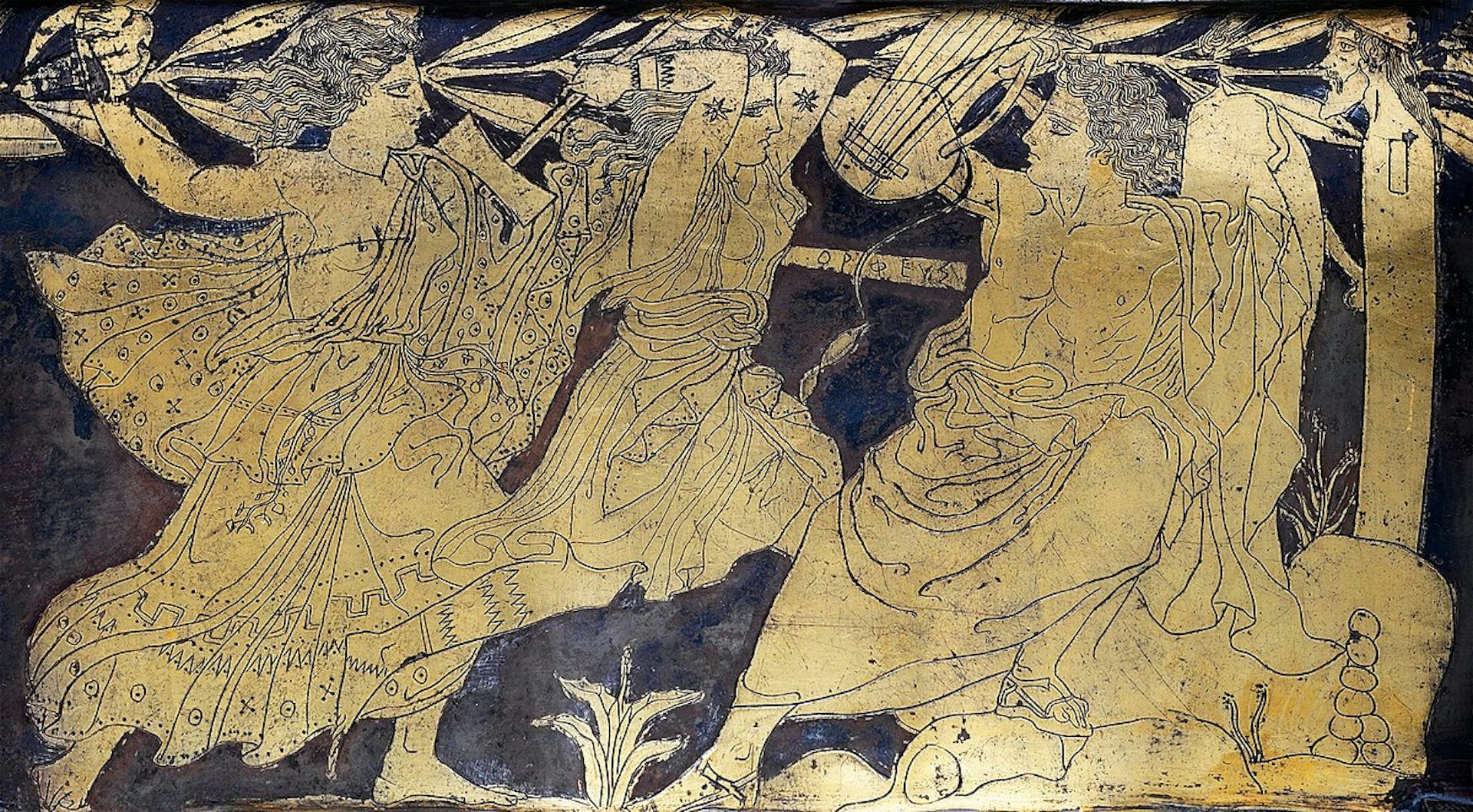

Silver kantharos showing the death of Orpheus (ca. 420–410 BCE).

Vassil Bojkov CollectionCC BY-SA 4.0But various sources had different ideas about why Orpheus was killed. In one version, Orpheus had offended Dionysus somehow (either by denying his divinity, neglecting to honor him in his music, or spying on his mysteries), so Dionysus sent his maenad worshippers to murder him.[30]

In other sources, it was the female sex as a whole that Orpheus had offended. When he lost Eurydice, Orpheus either shunned women completely (in favor of homosexual relationships), became a vicious and outspoken misogynist, or convinced the husbands of the women of Thrace to accompany him on his wanderings. Because of this, he was killed by a band of angry women.[31]

In the version of the myth recorded by Plato, on the other hand, Orpheus’ death was punishment for his cowardice: because he would not die for a woman, he ultimately met his end at the hands of women.[32]

Another strange version of the myth makes Aphrodite responsible for Orpheus’ death. When Aphrodite and Persephone both competed for the affections of the handsome Adonis, Zeus ordered Orpheus’ mother Calliope to resolve their dispute.

When Calliope ruled that each should possess Adonis for half of the year, Aphrodite was dissatisfied and punished Calliope by devising a creative way to get her son Orpheus killed: she caused all the women of Orpheus’ native Thrace to fall in love with him at once. When the women each tried to take Orpheus for herself at the same time, they tore him limb from limb.[33]

In one final version, Orpheus was not killed by women at all but by Zeus, who struck him down with a lightning bolt as punishment for teaching mortals the mysteries of the gods (possibly writing).[34]

However varied these different accounts of Orpheus’ death, most of them involved him being brutally torn apart. Many sources told of how his head, still singing sweetly or even delivering fateful oracles, floated down to the island of Lesbos.

After being buried (by either the Thracians, the Lesbians, or the Muses), the gods honored Orpheus by turning his lyre into a constellation.[35] His tomb was said to have been located either in Thrace,[36] Macedon,[37] or Lesbos.[38]

Roman floor mosaic showing Orpheus surrounded by animals (3rd century CE). Regional Archaeological Museum of Palermo, Palermo, Italy.

Giovanni Dall'OrtoCC0Worship

Orphic Literature

As the most important musician of myth, Orpheus came to be regarded as the author of a body of philosophical and theological poems—what is known today as “Orphic literature.” Orpheus’ role as the founder of Greek mystery cults begins with these poems.

It goes without saying that none of the ancient Orphic literature was actually written by the mythical (and probably largely fictional) Orpheus. The earliest Orphic literature probably dated to around the end of the sixth century BCE, and very little of it survives today. Much of what is known of this early literature comes from the writings of Plato in the early fourth century BCE[39] and from the Derveni Papyrus, a fragmentary commentary on an Orphic poem from the late fourth century BCE (discovered in 1962).

The bulk of Orphic literature deals with theogony—that is, the birth of the gods and the cosmos.[40] The Orphic theogonies tended to differ from more traditional Greek theogonies, such as that of Hesiod, on important points. For example, the Orphic theogonies placed obscure figures such as Nyx, Aether, Protogonus, and Phanes ahead of the earliest Hesiodic gods.

Orphic literature also seemed to describe not one Dionysus but two, with the first Dionysus born of Zeus and his daughter Persephone before being killed and eaten by the Titans.

Other Orphic literature (such as the Katabasis) was eschatological, dealing with questions of death and the fate of the soul. Still other texts (such as the Teletae) outlined specific rites and rituals through which initiates into mystery cults (especially the Eleusinian Mysteries) could live a blessed life and secure eternal bliss for their immortal souls.

Some Orphic literature dates from a much later period. The Orphic Hymns, for example, are a corpus of 87 poems composed between the third century BCE and the second century CE. They address numerous gods—some familiar (Zeus, Dionysus, etc.), and others quite obscure (Aether, Sabazius, etc.)—and appear to have been used in actual rituals.

Even later than the Orphic Hymns are the Orphic Argonautica and the Lithica. The Orphic Argonautica is presented as an eyewitness account of the voyage of the Argonauts as told by Orpheus himself. It makes various references to Orphic cosmogony. The Lithica is a strange poem that describes the secret qualities of stones.

Orphic (and Other) Mysteries

There appear to have been societies in ancient Greece that used the Orphic literature ascribed to the mythical Orpheus as a guide to their lives and religious practices. These Orphic Mysteries (sometimes also called “Orphism” or “Orphic religion”) were thus “basically Orphic literature.”[41]

Followers of Orpheus (sometimes called Orpheotelestae, or “Orphic ritualists”) were already well known by the Classical period (479–323 BCE), being mentioned in the writings of Plato and other contemporary authors.[42] They were known for certain distinctive practices, including vegetarianism and, in some cases, abstinence from sex. They also used rituals to ensure a blissful afterlife for their immortal souls.

The Orphic Mysteries influenced and sometimes became confused with other ancient mystery cults. These included the Dionysian or Bacchic Mysteries, which were long believed to have borrowed important elements from the Orphic Mysteries;[43] the Eleusinian Mysteries, whose beliefs in the immortality of the soul closely resembled those of the Orphics; and Pythagoreanism, which, like Orphism, prescribed lifestyle rules such as vegetarianism.[44]

Pop Culture

Orpheus continues to exert a major presence in modern pop culture. The myth of his love for Eurydice was turned into several operas and ballets by composers such as Igor Stravinsky and, more recently, Harrison Birtwistle and John Robertson.

In literature, Orpheus has appeared in numerous works. Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus (1922) remains well known. Margaret Atwood’s Orpheus and Eurydice cycle of poems (1976–86) and Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice (2003) retell the myth from Eurydice’s perspective.

Other authors have adapted the myth to new settings: Poul Anderson, for example, transposed the tale to a futuristic science fiction setting in his 1972 novelette Goat Song. Orpheus also features in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman graphic novel series (1989–2015), where he is the son of Morpheus, the embodiment of dreams.

There are several famous cinematic and dramatic retellings of the Orpheus myth as well. Marcel Camus’ 1959 film Black Orpheus, adapted from Vinicius de Moraes' play Orfeu da Conceição (1956), sets the myth in twentieth-century Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval. Jean Cocteau’s Orphic Trilogy, consisting of the films The Blood of a Poet (1930), Orpheus (1950), and Testament of Orpheus (1959), is also based on the Orpheus myth.

More recently, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice was retold in Anaïs Mitchell’s 2010 musical Hadestown.