Orishas

A carved ivory vessel that once belonged to a king of Owo, by Yoruba artist (17th to 18th century).

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

The orishas (or oriṣas) are essentially the gods of the Yoruba pantheon. However, the term “orisha” cannot be easily defined. They are not merely deities; instead, an orisha “is a complex multidimensional unity linking people, objects, and powers.”[1]

There are more than 400 orishas in total (the precise number varies depending on the source). Each orisha is involved in daily human life in some way, and they are often called upon for assistance in navigating problems, both large and small. Naturally, some of these gods occupy a more prominent position in Yoruba religion than others (see below).

Pronunciation

English

Yoruba

Orisha Oriṣa Phonetic

IPA

[oh-REE-shah] /òˈɾìʃà/

Who is the most powerful orisha?

Crown of Obatala (Ade Obatala) by Yoruba artist (late 19th to early 20th century).

Museum of High ArtCopyrightThe orishas collectively control all the elements of the universe; however, each individual orisha’s power varies depending on their domain of authority. The most powerful orisha is undoubtedly the supreme god, Olorun (also known as Olodumare). Olorun’s domain is the infinite universe, the skies, and the heavens. The other Yoruba gods effectively function as his emissaries.[2]

Where do the orishas live?

The orishas live in the heavens, far above the earth. Most orishas cannot easily travel to the human realm, but certain gods were gifted with the power to act as messengers between the world of the gods and the world of humans. For example, in the Ifa religion of Yorubaland, both Ọrunmila and Eshu have the ability to travel between realms. They deliver messages to the humans and sacrifices to the gods.

How many orishas are there?

Kneeling female figures are popular in Yoruba religious art. They are meant to represent a suppliant of the orishas, by Areogun of Osi (late 19th or early 20th century).

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0The total number of orishas is open to debate, varying from 200 to over 1,700, depending on the source.[3] However, the most commonly accepted number is 401. The orishas are collectively known as “Orishanla” (a name that is also given to the creator god Ọbatala). [4]

The most important and powerful orishas number around a dozen; these are the deities who are most “active in earthly affairs and universal in Yoruba belief.”[5] The rest of the Yoruba pantheon is made up of lesser orishas and ancestors.

Origins of the Orishas

A statuette of Eshu for an altar, by Yoruba artist (late 20th century).

African Arts GalleryCopyrightAccording to one creation myth, in the beginning there was only one orisha, the “Divine Spirit,” who lived in a house at the foot of a sheer rock wall.[6] He had a slave called Eshu who attended to all his needs. But Eshu hated his master.

One day, Eshu climbed to the top of the cliff and pushed a large boulder over the edge. The boulder fell on top of the orisha’s house and crushed the Divine Spirit within. The god shattered into pieces, which were then scattered in all directions by the wind.

In this way, pieces of the Divine Spirit came to be found in all places and within all living beings, including the natural elements. Today, all 401 orishas—collectively known as Orishanla—contain a fragment of the divine.[7]

Carved breast-feeding woman thought to represent Oduduwa, by Yoruba artist (1890-1920).

Science Museum GroupCC0Another creation myth describes the violent birth of some of the most important orishas. This story begins with Orangun, the son of Yemaja and her brother Aganju (both primordial deities). One day, Orangun attacked and raped his mother and ended up impregnating her. Yemaja fled from her son in horror in the wake of this horrific act.

While fleeing from him, the goddess tripped and fell. Suddenly, sixteen orishas were born from her pregnant belly.[8] These included Olokun (the ocean); Osha (the lagoon); Shango (thunder); Oshun, Oya, and Oba (Shango’s three wives); Ogun (iron); Oke (the mountain); Oko (the farm); Aje (wealth); Sun; Moon; and Obaluaiye (disease), among others.[9]

List of Notable Orishas

The Yoruba pantheon contains hundreds of orishas. Together they created the universe and the human race, and all remain involved in humans’ daily lives. Each orisha has their own significance for the Yoruba people, though the precise worship and importance of individual orishas varies across Yorubaland. The most notable orishas are those connected with fertility—both human and agricultural.

Olorun

The brass bust depicts an unknown Yoruba king, by Yoruba artist (14th – 15th century).

British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Olorun, also called Olodumare, is the most powerful orisha of the Yoruba pantheon. He is the creator of the universe as well as the father of all other gods. Unlike some orishas, Olorun is not anthropomorphic (i.e., he does not resemble humans). Instead, he is a formless being.

Along with being the supreme god, Olorun is also the god of justice who judges the fate of humanity. It is Olorun who decides whether someone has a good heart and whether they are worthy of the gods’ favor. He also chooses when a person’s life is at its end.[10]

Olorun inhabits the heavenly home of the orishas and rarely descends to the human world. However, he is always watching and listening to human wishes and complaints. His faithful servant and messenger, the chameleon Agemo, carries Olorun’s commands to both orishas and humans.

Ọbatala

The ogbin obatala drum belongs to the Ijebu-Yoruba peopple of Nigeria.

Fowler Museum at UCLACopyrightỌbatala is one of the oldest orishas and the second highest divinity, after the sky god Olorun. He is best known as the creator of the world, including the solid land that humanity inhabits. He is also called the creator and sculptor of humans, a task assigned to him by Olorun.

According to myth, Ọbatala became inebriated while creating the first humans and accidentally malformed his creations. As a result, he is now considered the guardian of disabled people.[11]

Ọbatala is an anthropomorphic deity, closely resembling his peasant worshippers.[12] This representation makes him a particularly relatable and appealing orisha for worship. He is a god of purity and creativity, and his worshippers often invoke his help with conception and fertility.

Oduduwa

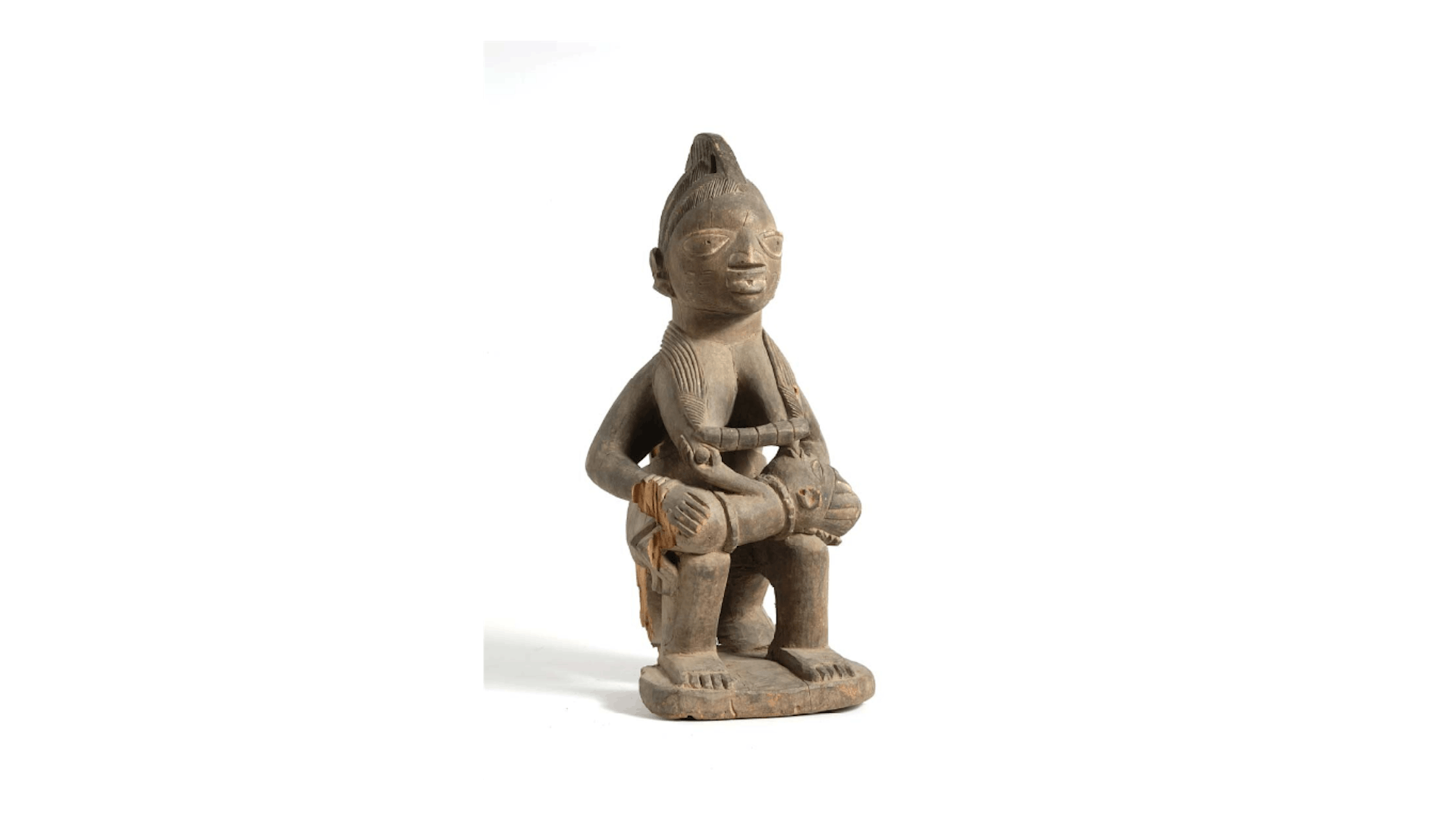

A seated figure of a breast-feeding woman, possibly Odudua. Yoruba artist (pre-1959).

Collectie Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen CC BY-SA 4.0Oduduwa is the name of both a primordial deity and a deified ancestor. As a primordial deity, she is the wife of Ọbatala and assisted him in the creation of humans. Oduduwa and Ọbatala are often considered two halves of a single being, symbolized by a white calabash (a kind of gourd).[13]

After Ọbatala became intoxicated while creating the first humans (see above), Oduduwa took over for him. She is therefore considered the mother of the Yoruba people.

Ọrunmila

Ifa diviners would tap on their divination trays with these wands while praising Orunmila. Yoruba artist (20th century).

Kruizenga Art MuseumCopyrightỌrunmila, also known as Ifa, is the god of divination and the first ever babalawo (oracle) of the Yoruba people. He is also the primary deity of the Ifa religion. Ọrunmila is one of the only gods who can travel unimpeded between the realm of the orishas and the human realm. Because of this, he carries messages between the humans and orishas.

Along with divination, Ọrunmila is also the god of wisdom and fate. This allows him to predict the future and relay those predictions to his oracles on earth. His worshippers consult these oracles for advice on all matters.[14] Ọrunmila is one of the most popular orishas, widely worshipped throughout Yorubaland.

Eshu

Wooden figure representing the god Eshu, by Yoruba artist (1880–1920).

Science Museum GroupCC0Eshu (or Eṣu) plays a vital role in the Ifa religion by carrying messages and sacrifices to the gods from human worshippers. Like Ọrunmila, he is one of the only gods who can travel between the two worlds. He ensures that the correct sacrifices are always offered to the orishas.[15]

Eshu is also known as Legba or Elegba in the diasporic Yoruba religions. In this iteration, he is a mischievous trickster orisha, as well as the guardian of thresholds and crossroads. Eshu is also responsible for unpredictability and confusion.

Many of Eshu’s myths involve him playing pranks on the god Ọbatala.[16] By contrast, Eshu has a close relationship with the divination god Ọrunmila. Eshu is one of the most popular and recognizable orishas of the Yoruba religion.

Yemaja

An ibeji or figure of Yemaja (Iemanja) from the Museo Afro Brasil carved by a Yoruba artist and dated to the 20th century. Image photographed by Sailko, (2013).

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY 3.0Yemaja (or Yemọja) is the primordial goddess of water. Unlike other water deities, whose powers only extend to certain bodies of water, Yemaja has dominion over all water and all other water orishas. In fact, she is revered as the mother of all orishas.[17]

Yemaja is predominantly a goddess of fertility and childbirth; as such, her worshippers are mainly female. They believe that the water from Yemaja’s oceans and rivers has the ability to heal infertility. Yemaja is also a protector of women during childbirth.

Shango

A carved votive figure of Shango on horseback, by Toibo of Erin (1920s-1930s).

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0Shango (or Ṣango) is the god of thunder, lightning, and other formidable elements of nature. As such, he is one of the most powerful and feared of all orishas.[18] Tradition holds that the sound of thunder comes from Shango beating his drum to summon lightning. The god is well known for having three wives—Oshun, Oya, and Oba—all of whom control stormy weather and violent winds.[19]

Shango has many myths associated with him, some of which tell of his ability to breathe fire. The battle-ax (or oshe) serves as a symbol of the god, communicating his ferocity. In most myths, Shango is portrayed as a deified ancestor who was once a tyrannical ruler of the Oyo Kingdom.

Oshun

Olójú Foforo (The Owner of Deep-Set Eyes) is a carved mask depicting a priestess of Osun, by the artist Dàda (c.1880 - 1954).

Yale University Art GalleryCopyrightOshun (or Ọṣun) is the goddess of the Oshun River and the patron of the town of Osogbo. She is also the goddess of love, beauty, and diplomacy. Though primarily known as a peacemaker, Oshun will not hesitate to fiercely protect her followers. She is one of the three wives of Shango, the god of thunder and lightning.

Oshun is a benevolent and generous goddess, closely associated with kingship and the royalty of the Osogbo Kingdom. Most of her myths tell the foundation story of Osogbo, next to the Oshun River. The Ọṣun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria is still a popular place of worship for her followers. [20]

Oya

An equestrian shrine figure (Ojúbọ Ẹlẹ́ṣin) depicting a priestess of Ọya, by Yoruba artist (1920 - 1940).

Yale University Art GalleryPublic DomainOya is a fearsome goddess of storm winds, tornadoes, hurricanes, and the Niger River. She is another one of Shango’s wives (along with Oshun and Oba).

Oya is a temperamental deity who is easily offended. She therefore requires frequent sacrificial offerings and prayers to prevent destructive storm winds. Along with the wind, she is the guardian of the gates of death, where she acts as a gatekeeper between the human world and the afterlife.[21]

Obaluaiye (Babalú-Ayé)

A carved wooden figure of Shopona, mounted on a horse. Yoruba artist (n.d)

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Obaluaiye (also known as Babalú-Ayé or Sòpònno) is the god most closely associated with disease, especially smallpox. He is greatly feared for his power to destroy entire cities with pestilence.

Obaluaiye requires constant sacrifices to ensure that he does not send down a plague. If the god does decimate a region, he demands to be thanked for the destruction, no matter how horrible.[22]

Ogun

A blacksmith's staff (opa ogun) use for ceremonies in honor of Ogun by Yoruba artist, (20th century).

High Museum of ArtCopyrightOgun is the god of iron, blacksmithing, warfare, and hunting. Warriors and hunters invoke the god for protection before battle or hunting. He is also known as a remover of barriers and obstacles.[23] Ogun is primarily known for giving humanity the gift of iron and for teaching them metalwork.

Olokun

A pot from a woman's shrine to Olokun, by Edo artist (16th to 19th century)

British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Olokun is the orisha of the primordial ocean. According to Yoruba creation mythology, Olokun inhabited the world long before Ọbatala created the earth; she lived in a world of sea and mist, while the other gods occupied the sky.[24]

In some traditions, Olokun is a male sea god, while in others she is a goddess—the same deity as Yemaja (see above). Olokun is an orisha of fertility whose followers believe her waters can cure infertility. Though she is a fearsome and temperamental goddess, known to wreak havoc, Olokun is also a fierce warrior who protects her worshippers—especially sailors.[25]

Orisha-Oko

Wooden dance mask representing a follower of Orisha-Oko, by Yoruba artist (pre-1908).

British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Orisha-Oko is the god of agriculture, harvesting, and farming. He is a popular orisha in Yorubaland; farmers call upon him whenever they are experiencing poor crop yields. In his capacity as an agricultural deity, he is also a fertility god who is responsible for the fertility of the farmlands.[26]

Ibeji

Pair of twin figures (Ère Ìbejì) by Yoruba artist (late 19th-early 20th century).

Brooklyn MuseumPublic DomainIbeji is both the god of twins and the Yoruba word for twins. In Yoruba tradition, twins are thought to possess one soul within two bodies; both are part of the same god.[27] To the Yoruba people, the birth of twins is considered a good omen and a blessing from the gods.

Osanyin

Wooden figure with a hole on top to hold medicine from an Osanyin shrine, by Biro (1959).

British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Osanyin is the orisha of herbal medicine, herbalists, and healing. He is also a divinity of forests, trees, and hunting. The god is believed to heal those suffering from mental illness or from ailments attributed to hexes or witchcraft.

Osanyin is able to transform into a bird to travel the world, observing humankind and protecting his followers from harm.[28]

Types of Orishas

A religious object made from a buffalo horn and cowrie shells, by Yoruba artist (n.d).

British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Scholars usually divide the orishas into three categories: primordial deities, natural deities, and deified ancestors.

The primordial deities existed long before the creation of the earth and humanity. These early gods include Ọbatala (the creator of the world), Oduduwa (Ọbatala’s wife, who helped create the first humans), and Ọrunmila (the god of divination).[29]

Natural deities are the personifications of natural forces and phenomena. These are the orishas of the seas, lakes, rivers, trees, and weather. Notable nature gods include the three wives of Shango—Oshun, Oya, and Oba—who are all river deities, as well as Orisha-Oko (the god of agriculture) and Osanyin (the god of herbal medicine). Despite being the god of thunder and lightning, Shango is not considered a nature deity but rather a deified ancestor.

Deified ancestors are people who once lived on earth but who were transformed into orishas upon their death. These ancestors are usually notable figures from human history, such as kings. Once an ancestor is deified, their descendants are able to claim a divine origin.[30] The most notable deified ancestor is Shango, who was once a mortal king of Oyo. He later became the fearsome god of lightning and thunder.

Worship

Objects that would accompany a divination tray (opon ifa) and used by a diviner (babalawo) in the Ifa religion, Yoruba artist (19th century).

Museum of Witchcraft and MagicCopyrightWorship of the orishas is the most important aspect of the Yoruba religion; as such, it assumes a range of different forms and functions. Worship may include prayers, festivals, songs, music, and sacrifices, among other rites and practices. Priests play an important role in the correct execution of religious ceremonies.

During religious ceremonies, songs of praise are often sung to invite the presence of a god. Musical instruments, such as drums, are a crucial addition to these praise songs, as is the use of praise names for the specific deity being called upon. For example, in a musical invocation of Ogun, the phrase “Òsìn Imdlé” (“Chief of Divinities”) may be used as a praise name.[31]

Sacrifices to the orishas are another important aspect of traditional Yoruba religion. Several different types of sacrifices are made, including thanks offerings, votive offerings, propitiatory offerings (i.e., offerings to appease the gods), and preventive offerings.[32] Propitiatory offerings are often made when there is a crop failure or disease outbreak. Orisha-Oko and Obaluaiye are often the recipients of this type of sacrifice.

Ifa is a particular form of traditional Yoruba religion. It centers on divination and communing with Ọrunmila, the god of divination (who is called Ifa in this context). In this worship, babalawos (or oracles) of Ifa are consulted in order to predict future events and ask for advice. The oracles read cowrie shells to determine Ọrunmila’s answers to his worshippers’ questions.