Odin

Overview

Widely worshiped by the Germanic peoples of the Middle Ages, Odin, furious lord of ecstasy and inspiration, was the highest of deities and the chief of the Aesir tribe of gods and goddesses.

Known as “all-father,” among many other epithets, Odin was usually depicted with one eye and a long beard. He would often be accompanied by his familiars—the wolves Geri and Freki, and ravens Huminn and Muninn—and rode an eight-legged horse named Sleipnir.

Befitting his kingly stature, Odin was also a mighty warrior—it was said that he never lost a battle; there were even some who believed he could not lose a battle.

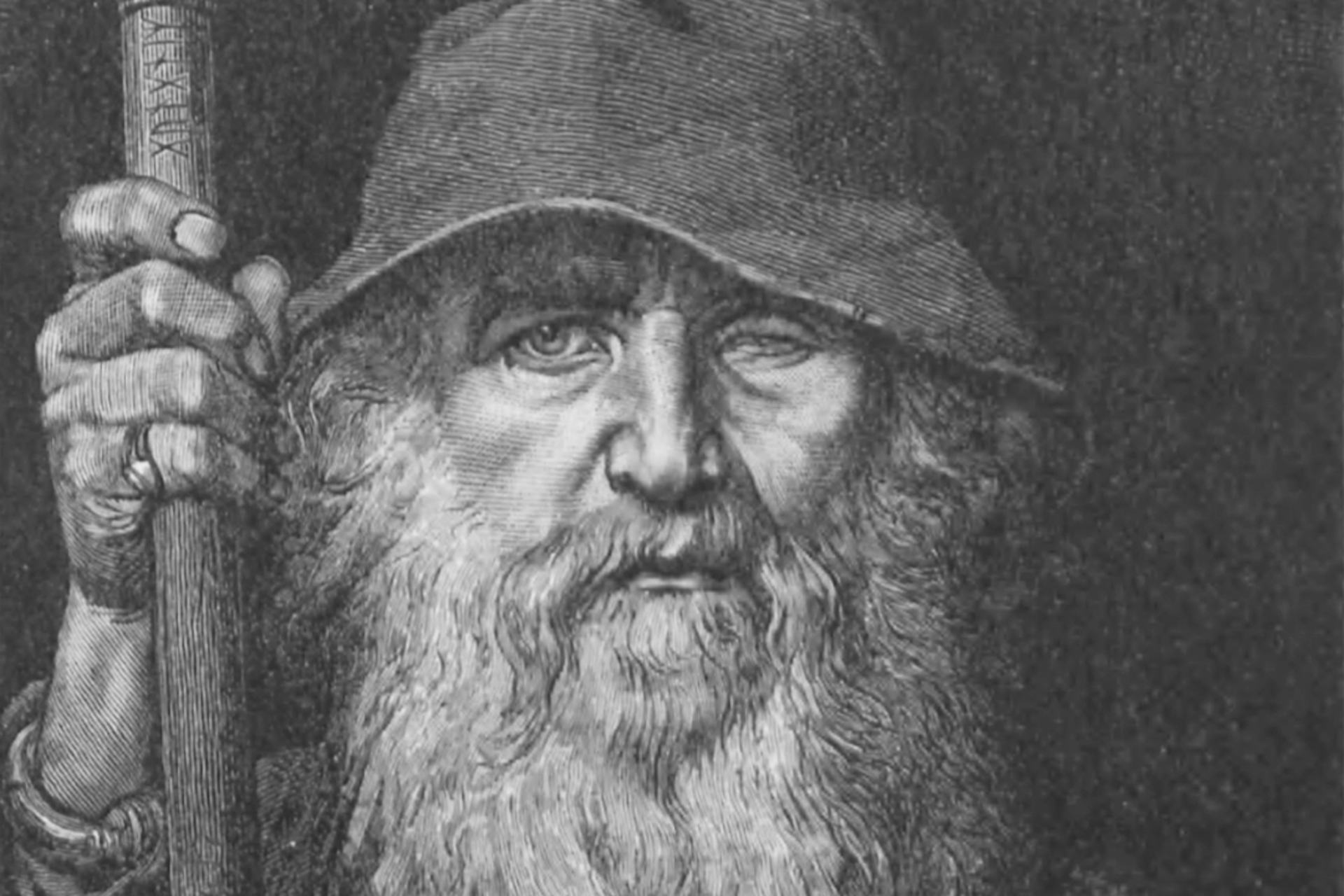

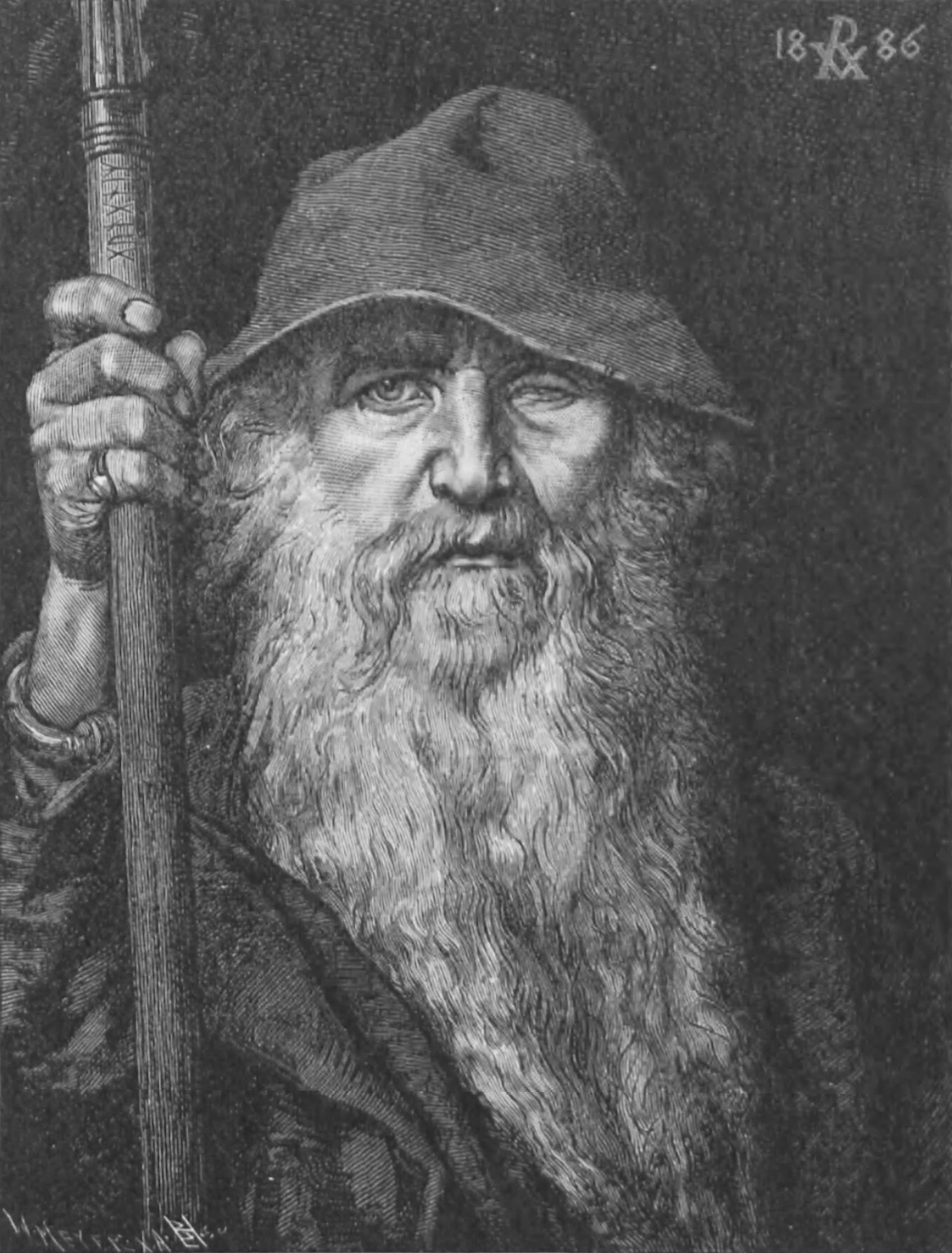

Oden som vandringsman, or Odin as Wanderer by Georg von Rosen (1886). This image appeared in an 1893 Swedish translation of the Poetic Edda (also known as the Elder Edda), a compilation of Norse mythic poetry that serves as the most important single source for the history of Norse mythology. This image better captures Odin as he appeared in myth. It has been said that J.R.R. Tolkien based the character of Gandalf on Odin.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDespite his military prowess, Odin defied many conventions of the warrior-king archetype so highly idealized by the Norse. While Odin kept his court in the hall of Valhalla located in Asgard—one of the Nine Realms in Norse mythology—he preferred to wander in the guise of a traveler.

He sought knowledge above all else—of his enemies and the future—and courted shamans, seers, and necromancers in order to attain it. He spoke in poetry and riddles and commanded beasts, even taking their forms upon occasion. Though hero gods, such as the mighty Thor, fought with brute strength and bravado, the trickster god Odin dismissed these tools in favor of craft and cunning.

Etymology

The name “Odin,” rendered in the Old Norse as Óðinn, derived from two words: óðr, meaning “fury, rage, passion, ecstasy, or inspiration,” and the masculine definite article suffix -inn. The name has been translated to mean “the Fury.” The German chronicler Adam of Hamburg proposed this as a literal translation in his eleventh-century work, the History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen.[1] Other translations included “the furious,” “the passionate,” “the inspired,” and, more appropriately, “the inspiring.” Odin was thought to inspire fury, passion, and ecstasy even as he was defined by such traits.

The name fit Odin's character nicely, as a kind of inspired fury and passion permeated his many thoughts and actions. In all his personae—as warrior and king, shaman and seer, traveler and trickster—Odin channeled a focused intensity and single-mindedness of purpose. Such focus was a boon; knowledge, magic, and war—among other domains over which Odin held sway—all necessitated such intensity.

Odin was recognized and commonly referred to in other Germanic languages: he was known as Wōden in Old English, Wōdan in Old Saxon, and as Wuotan and Wotan in Old German. The god’s name also lent itself to the word “Wednesday,” meaning “Wōden’s day.”

Attributes

Odin’s chief attributes were his wit, wile, and wisdom. Having cultivated the magical arts of seidr, the set of rituals enabling foresight, Odin could see the future and commune with spirits and the dead. He was also a shapeshifter who could take the form of snakes, eagles, and other powerful creatures. Additionally, Odin spoke in poetic verse and had the power to bewitch humans into committing deeds outside their characters.

Odin was often depicted with a staff or spear, but otherwise wielded no specific weapons. On multiple occasions, he consulted with the decapitated and embalmed head of Mimir which revealed many secrets to him. His magnificent throne Hlidskjalf offered a complete view of all Nine Realms.

Odin by Lorenz Frølich (1844). Odin is seen here in all his power, with wolves Geri and Freki and ravens Hunnin and Munin beside him. Scenes like this, depicting Odin as a mighty warrior-king resplendent in his glory, are typical of the revival of Germanic myth and imagery during the nineteenth century (often in the service of German nationalism). These depictions are not always in keeping with his mythological standing, however. It should be noted that there are virtually no images of Odin from the early centuries of the Common Era, when his cult thrived.

Statens Museum for KunstPublic DomainOdin’s familiars were the wolves Geri and Freki, who traveled alongside their master and scoured battlefields for the corpses of fallen warriors. Odin also kept a pair of ravens known as Huninn and Muninn. These ravens served as spies and informers, leaving each morning to travel the nine worlds and returning each night to tell Odin of all they saw.

Family

Although much about Odin's origins has remained obscure, consensus held him to be the son of the Bestla and Borr. Bestla, his mother, was a frost giant, one of the races of the jötnar, or non-human creatures that included dwarves, elves, trolls, and giants. While little was known about Odin’s father Borr, Borr’s father Buri was licked out of a salty ice formation by a magical cow. According to Snorri Sturluson, Icelandic author of the Prose Edda (also known as the Younger Edda and Snorri’s Edda):

She [the cow] licked the ice-blocks, which were salty; and the first day that she licked the blocks, there came forth from the blocks in the evening a man's hair; the second day, a man's head; the third day the whole man was there. He is named Búri: he was fair of feature, great and mighty. He begat a son called Borr...[2]

Bestla and Borr had two more children, boys called Vili and Vé. As Sturluson succinctly continues:

...[Búri] begat a son called Borr, who wedded the woman named Bestla, daughter of Bölthorn the giant; and they had three sons: one was Odin, the second Vili, the third Vé.[3]

In later life, Odin married Frigg (also Frija, Fria, and Frige), a goddess associated with wisdom, forethought, and divination; Frigg was likely connected to the goddess Freya. With Frigg, Odin sired a son, Baldur (a name meaning “lord”), who was known as the wisest and fairest of the Aesir.

According to most traditions, Odin fathered children with many other women. With the jötunn Jord, Odin had Thor, the hammer-wielding god who commanded thunder, lightning, and storms. With Gridr, another of the jötnar, he had the vengeful Vidarr, who according to prophecy was to rescue Odin from the brink of death during Ragnarök. With the giant Rindr, Odin fathered Váli, whose chief purpose was to avenge the death of Baldur.

Less reliably, Odin was also said to have fathered Tyr, Heimdall, Bragi, and Hodr. Although modern manifestations of Odin, particularly those in Marvel comic books and movies, have depicted him as the adoptive father of the mischief-maker Loki, this claim was never made in any sources of Norse mythology. Loki was, however, sometimes described as the brother or half-brother of Odin.

Family Tree

Mythology

As the “all-father” and chief god of the diverse Norse pantheon, Odin figured prominently in all of the central mythological traditions—from the creation of the first humans and the Aesir-Vanir War that united the gods into a single pantheon, to the prophecies of Ragnarök marking the end of time.

Origins

Despite his importance in the mythic traditions of the Norse, the details of Odin’s origins were not well understood. He appeared in early Roman sources, such as Tacitus’ Germania of the first century CE, as Mercury—another deity known as a traveler, trickster, and transgressor of boundaries. Tacitus claimed that by the first century, Odin had been established as the central god among a variety of Germanic groups.

Only Sturluson’s thirteenth century Ynglinga Saga attempted an early history, describing Odin as the king of Asgard, a ruler of great strength who blessed warriors and accepted many sacrifices. Most viewed this as a late attempt to impose order on the character of Odin, who seemed to emerge fully formed in the older mythic sources.

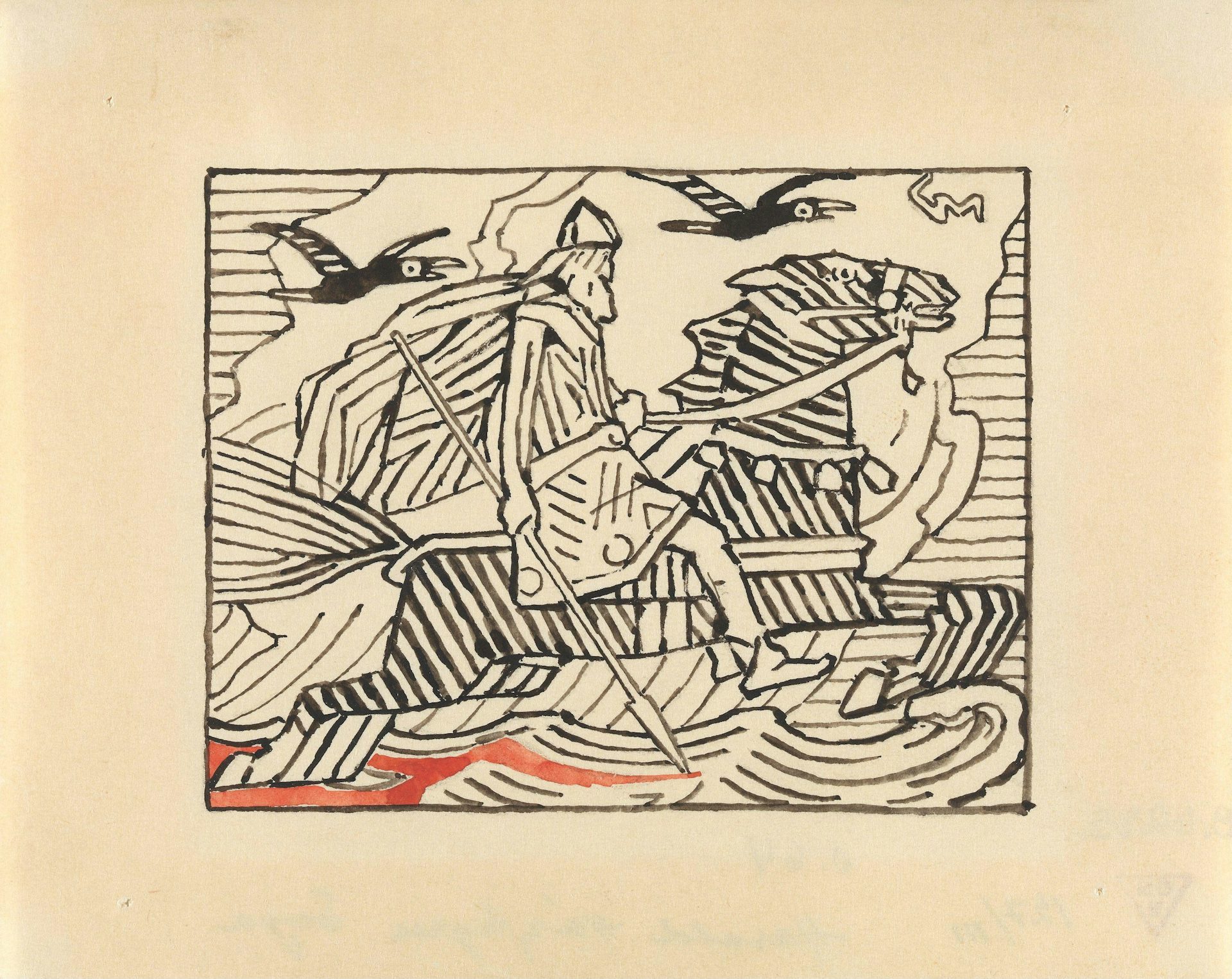

Odin as depicted by Gerhard Munthe in a preparatory drawing (ca. 1895-1899) for Snorri Sturluson's Saga of Harald Fairhair.

National Museum, NorwayCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Some of the same ambiguities surrounded the Norse origin of humankind. Traditionally, the first humans were Ask and Embla, a male and female. Little was said about their actual creation, however, with different traditions holding that they were either formed by gods or dwarves.

When a trio of gods—including Odin, Lodur, and Hoenir—found Ask and Embla, they were lifeless husks. Pitying the creatures, the three gods decided to endow Ask and Embla with the gifts of life and sense, each choosing a separate gift to bestow upon them.

According to the Völuspá, the best known of the poems making up the Poetic Edda, Lodur granted the gift of blood, Hoenir gave sense, and Odin, befitting his status as god of passion and inspiration, offered soul and enlivening spirit.

From the Aesir-Vanir to Ragnarök: Odin in the Völuspá

Odin’s part in the Aesir-Vanir War and the ensuing settlement which unified the gods placed him at the center of another kind of creation story. A cataclysmic conflict believed by the Norse to be the first war in history, the Aesir-Vanir War marked a seminal moment in Norse thought, as the Trojan War did for the Greeks.

The Aesir and Vanir constituted two separate tribes of deities. Led by Odin, the Aesir of Asgard were a tribe of fearsome warriors whose members included Frigg, Thor, Baldur, and Vidarr. By contrast, the Vanir hailed from Vanaheimr (a separate region and one of the Nine Worlds in Norse thought) and were made up of fertility deities and magicians who cultivated seidr, such as Freya and Gullveig the thrice-born. The tribes represented the two halves of an archetypal dichotomy—the Aesir serving as masculine warriors, and the Vanir fulfilling a feminine role as magicians.

The Wild Hunt of Odin by Peter Nicolai Arbo (1872). The painting is alternately titled Åsgårdsreien in Norwegian in reference to the Aesir group of deities of the realm of Asgard, led by Odin.

National Museum, NorwayCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Some historians have proposed that the mythic Aesir-Vanir War reflected the actual historical conquest of Northern Europe. Beginning in the second and third centuries CE, the local fertility cults were displaced by the advances of the more warlike Germanic tribes.[4] In this context, Odin’s popularity and importance became easier to understand. As both a warrior and a magician, Odin was a deity that uniquely straddled the divide between the two cultures. He was a conciliatory figure that may have helped to bridge the gap between the displaced and their displacers.

The story of the Aesir-Vanir War was related in the Völuspá of the Poetic Edda. It was told by a völva, or seer, being interrogated by Odin. This völva turned out to be Gullveig, whom the Aesir tortured and killed several times during the war, only for her to be reborn each time. While details of the conflict were sparse, the völva established that the war was long and harsh, as the Aesir struggled to deal with the magic of the Vanir:

The war I remember, the first in the world, When the gods with spears had smitten Gollveig, And in the hall of Hor had burned her, Three times burned, and three times born, Oft and again, yet ever she lives.[5]

The portion of Völuspá dealing with the Aesir-Vanir War ended with this mysterious and much-puzzled-over passage that suggested the endless nature of the conflict and hinted at Odin’s role:

On the host his spear | did Odin hurl, Then in the world | did war first come; The wall that girdled | the gods was broken, And the field by the warlike | Wanes [the Vanir] was trodden.[6]

Interestingly, this last passage featured Odin wielding a weapon. This portrayal stood in contrast to Odin's usual characterization, where he was said to have inspired others to fight for him rather than taking direct action himself. His favorites were the valkyries, the winged female warriors who decided the fates of all who fought in battles, and the berserkers, fighters who were said to be intoxicated with Odin’s furious bloodlust.

When both Aesir and Vanir realized that the conflict would likely drag on into eternity, they opted for peace and exchanged prisoners to serve as wards. Odin sent Hoenir, who helped animate humanity, and the wise Mimir. The Vanir delivered Njordr and his son Freyr. The peace lasted, albeit tenuously. At one point, the Vanir came to suspect that Mimir was sent to them as a spy and saboteur, so they killed him and sent his head back to the Aesir. Ever inventive, Odin embalmed the head with herbs and spoke charms he learned from runic study. His magic animated the head, which from then on told Odin many secrets.

The “Fate of the Gods”

As the Völuspá proceeded, the völva, having won Odin’s approval with her storytelling, transitioned from a telling of the past to a foretelling of the future. The poem culminated with a prediction of Ragnarök, or ragna rök, literally translated as the “fate of the gods,” a term for the sequence of events that would result in Odin’s demise, the end of the world, and its eventual rebirth. According to the völva, Ragnarök would be marked by terrible violence as the proper order of existence was overturned and inverted:

Brothers shall fight | and fell each other, And sisters' sons | shall kinship stain; Hard is it on earth, | with mighty whoredom; Axe-time, sword-time, | shields are sundered, Wind-time, wolf-time, | ere the world falls; Nor ever shall men | each other spare.[7]

Odin himself, she predicted, would be consumed by the monstrous wolf, Fenrir. Ultimately, however, after the world died and was reborn, the gods would return to celebrate the deeds of the great all-father.

Odin and the Thirst for Knowledge

Odin’s quests for knowledge comprised a significant portion of his mythic doings. No barrier, custom, or law could stand in his way. Not even death prevented from indulging his lust for knowledge.

Odin appears on his eight-legged horse Sleipnir in an 1760 Icelandic Prose Edda.

Royal Danish LibraryPublic DomainHis thirst for knowledge colored most everything about Odin, from the company he kept to his personal appearance. Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse, helped Odin to travel speedily throughout his realm. His raven familiars, Huminn and Muninn, dutifully flew through the worlds, leaving each morning and returning at supper. They informed Odin of everything they saw. Odin even sacrificed his eye for knowledge. He threw it into the spring of Mimir the wise, and it was said that Mimir drank mead every morning as a result of Odin's sacrifice.

Odin, the Runic Alphabet, and Yggdrasil

In another central myth, Odin discovered the knowledge of runes and delivered it to humankind. The very first Germanic alphabets were made up runes; these were pictographic symbols that worked as letters, with each rune standing for a different sound. Crucially, the runes also embodied certain cosmic powers. Thus, to know a rune meant knowing the cosmic power it symbolized, and knowing it meant being able to wield it.

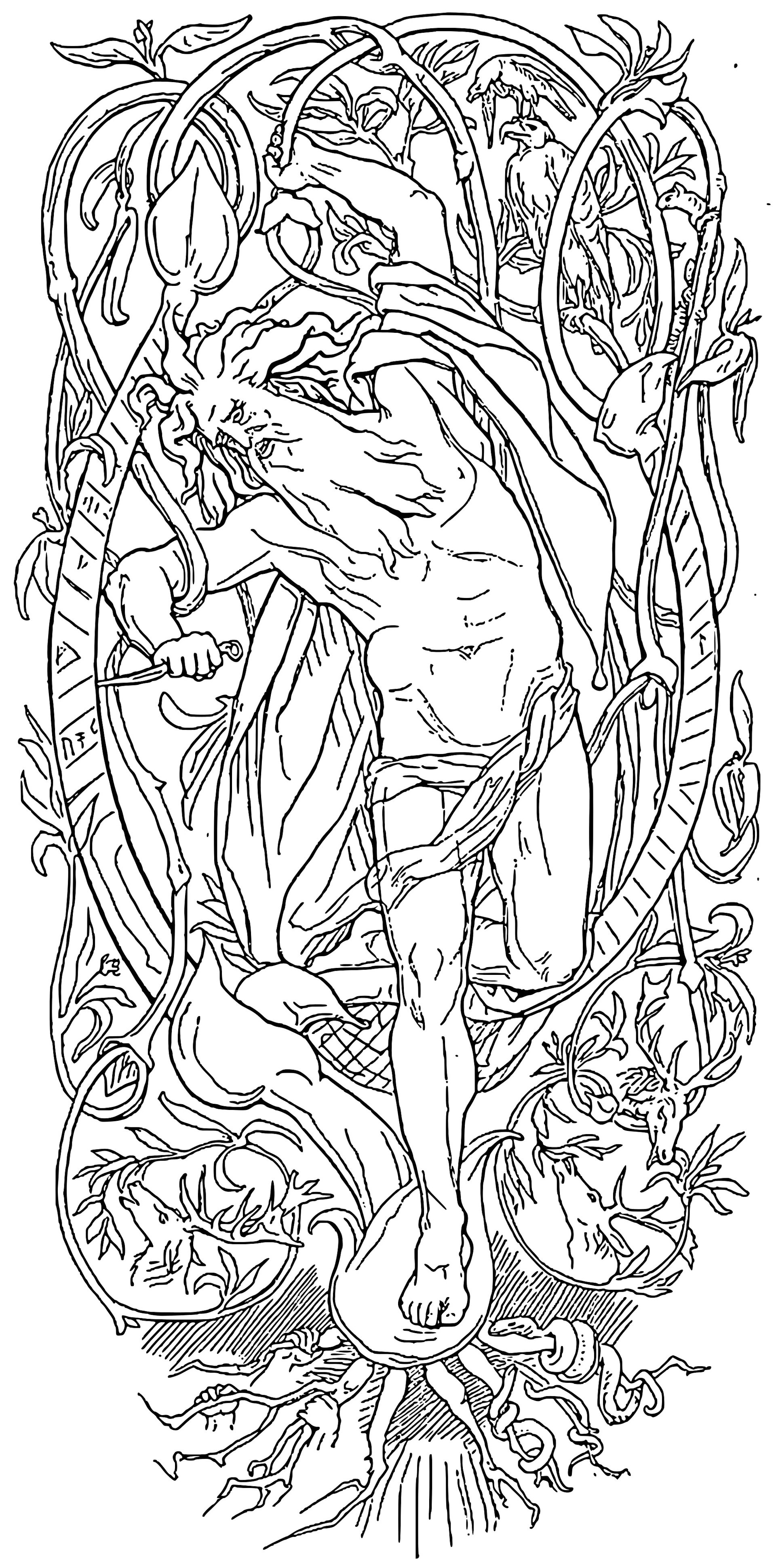

Odin achieved knowledge of the runes through a heroic act of self-sacrifice. He hung himself upon Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree that stood at the center of the created universe whose branches held the Nine Worlds. Hanging from the tree, Odin fasted for nine days, pierced himself with a spear, and cryptically offered himself to himself:

I ween that I hung on the windy tree, Hung there for nine nights full nine; With the spear I was wounded, and offered I was, To Odin, myself to myself, On the tree that none may know What root beneath it runs. None made me happy with a loaf or horn, And there below I looked; I took up the runes, shrieking I took them, And forthwith back I fell.[8]

Upon further study, Odin learned to decipher the runes. Such knowledge he gave freely to others:

Then began I to thrive, and wisdom to get, I grew and well I was; Each word led me on to another word, Each deed to another deed.[9]

The Sacrifice of Odin by Danish artist Lorenz Frølich (1895). The scene shows Odin hanging from Yggdrasil, the world tree. The similarities here with the crucifixion of Jesus have not been lost on scholars, and it should be kept in mind that the recording of Norse myth took place well after the introduction of Christianity in Northern Europe.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOdin and the Mead of Poetry

While Odin loved all sorts of drink, he thirsted particularly for the Mead of Poetry, a beverage said to impart the gift of poetry and knowledge unto its drinker. The Mead of Poetry came into existence through a complex series of events.

At the end of the Aesir-Vanir War, the gods sought peace. In order to mark their new peace, they each spit into a large jar, and from their spittle formed a wise man called Kvasir. There was no question Kvasir could not answer, and he roamed the world sharing his wisdom.

One day, Kvasir visited the home of the evil dwarves Fjalar and Galar, who murdered Kvasir and brewed the Mead of Poetry from his blood. When Fjalar and Galar crossed the wrong family of giants, they too were killed and the mead fell into the hands of the giant Suttung.

Odin tried to take the mead from Suttung first by tricks, then by treachery. He first disguised himself as a worker called Bölverk (“evil-doer”) and offered to harvest Suttung’s wheat in exchange for a draught of the mead. When Odin finished the work, however, Suttung refused even a sip of his precious beverage.

Odin then transformed himself into a snake and bored his way into the giant's mountain home. Once inside, he seduced Suttung’s daughter Gunnlöd, sleeping with her and drinking a horn of mead each night for three nights.

Odin swallowed the rest of the mead and, turning himself into an eagle, flew from Suttung’s lair leaving Gunnlöd to suffer her father’s wrath. While in flight, Odin spit his liquid loot into the vessels the Aesir gods left out for him, thus offering the Mead of Poetry to the world.

Odin and Gunnlöd both reach for the Mead of Poetry in this 1882 engraving.

duncan1890 / iStockPop Culture

In the nineteenth century, the emergence of German nationalism stimulated a revival of Germanic culture and a rediscovery of its mythic history. Odin, among other gods and heroes of old, was brought back into the realm of popular culture and has remained there ever since.

In recent years, Odin has been featured prominently in many pieces of popular media. In Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods (2001), Odin appeared as the character Wednesday and recruited Old Gods to battle against the New Gods. He also appeared in the God of War video game series.

Perhaps the most accessible manifestation of Odin was seen in the Marvel comic book franchise, where Odin was featured as the father of Thor. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Odin was portrayed by Anthony Hopkins and has appeared in several films. In these movies, as with most modern depictions of Odin, the all-father was cast as a wizened old leader who ruled benevolently over Asgard, fought honorably against various cosmic foes, and generally dispensed fatherly wisdom.

These representations revealed the ways in which Odin, the “all-father,” has become confused with other patriarchal deities, such as Zeus from Greek mythology. In reality, Odin ruled with great cynicism, fought dishonorably through trickery and subterfuge, and was seldom the fatherly figure he has become in recent years.