Mixcoatl

Overview

Mixcoatl (pronounced Meesht-Ko-Wattle) was the Aztec god of the hunt and the patron god of the Tlaxcalan people. Just as Huitzilopochtli guided the Mexica people to their eventual homeland, Mixcoatl led the Chichimec people to Tlaxcala. One of the few city-states to resist Aztec conquest, Tlaxcala ultimately sided with the Spanish conquistadors against the Aztec Empire.

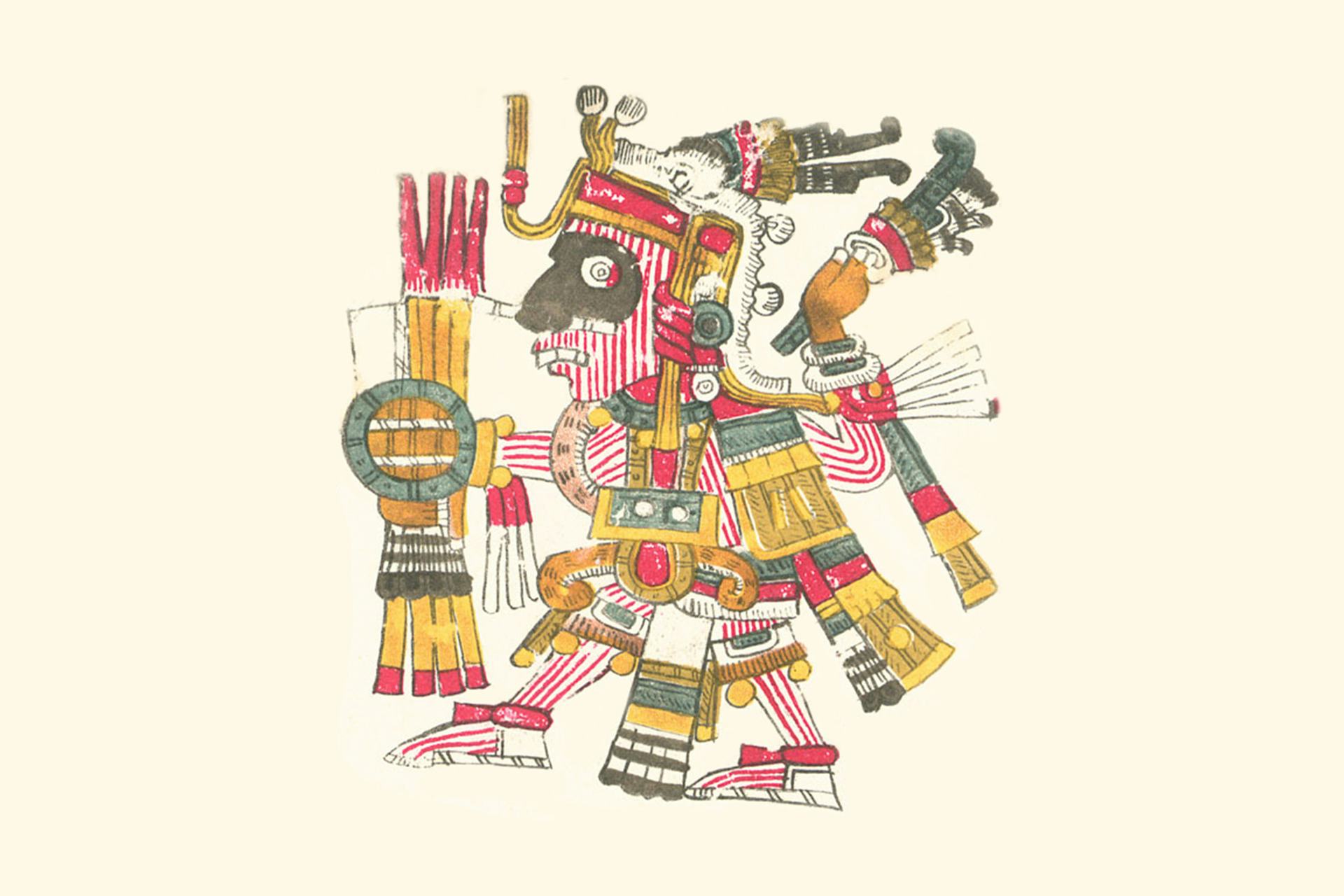

Mixcoatl appears in this detail from Codex Borgia.

FAMSIPublic DomainEtymology

Mixcoatl’s name, derived from the Nahuatl words mixtli (cloud) and coatl (snake/serpent), was generally translated as “Cloud Serpent.”[1]

A generally reliable translation of the Codex Ramirez rendered Mixcoatl’s name as “viper of snow,” a curious and possibly incorrect interpretation.[2]

Attributes

As a god of the hunt, Mixcoatl was often portrayed with his hunting equipment: a spear, a net or basket, and occasionally a bow and arrows.

Mixcoatl was usually depicted wearing a cloak of human skin; his own exposed skin was covered in red and white stripes.[3] He also wore a headdress adorned with an eagle plume. Note, in Aztec art, yellow skin generally indicates that the individual shown is wearing the flayed skin of a sacrifice victim.

Mixcoatl was more than just the god of the hunt; he also served as god of the Milky Way. Multiple sources described him as having a black face with star-like speckles, mirroring his celestial status.[4]

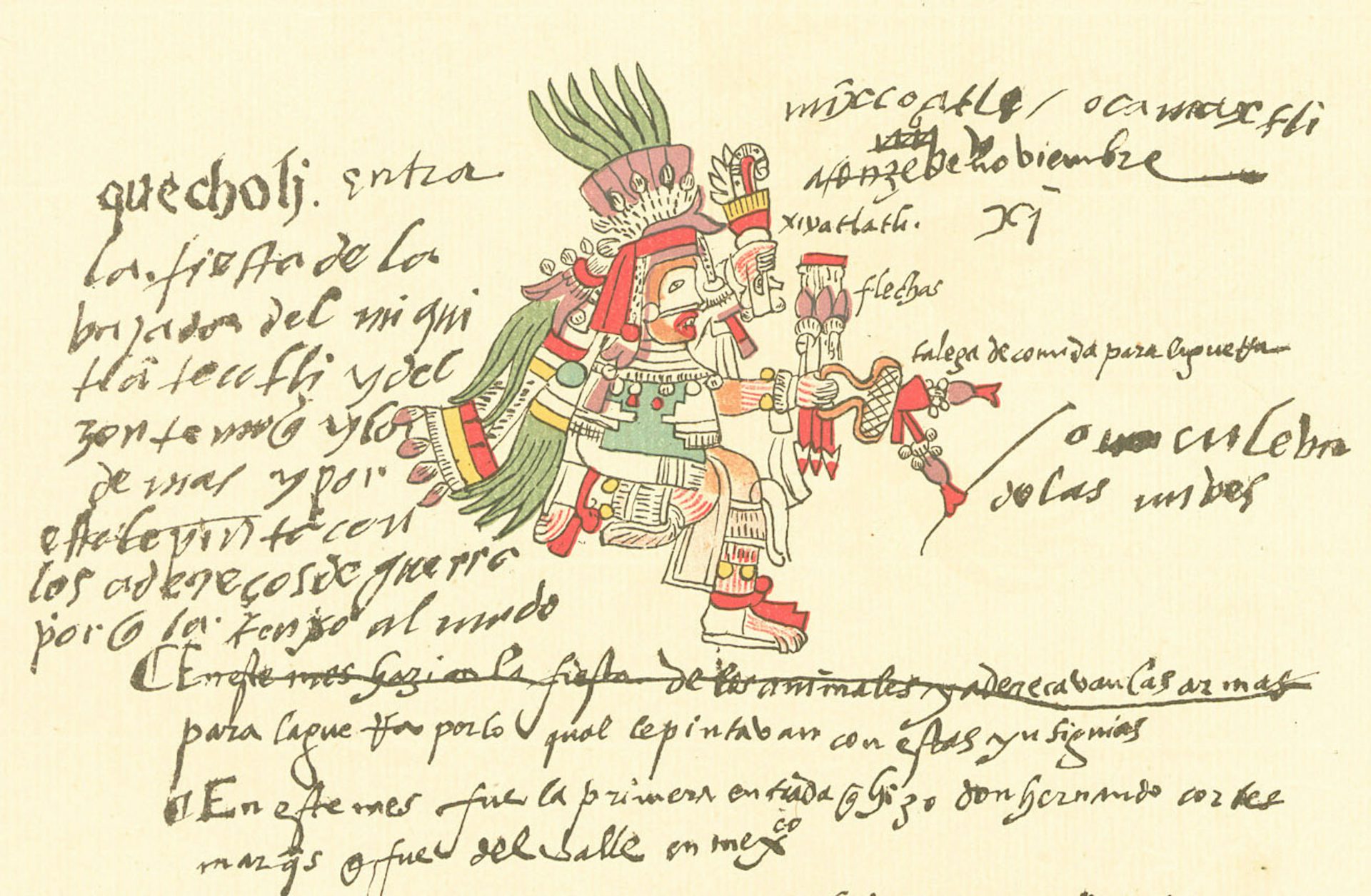

Found in the Codex Telleriano Remensis (c.1550), this image of Mixcoatl features much of his classic imagery, including his eagle plume and bow and arrow. His skin is decorated with red and white stripes, and he wears the flayed yellow skin of a sacrifice victim.

FAMSIPublic DomainFamily

The gods of the Aztec pantheon were dynamic and could take on new forms while the original yet persisted. Mixcoatl was a perfect example of this fluidity—he himself was simply an iteration of Tezcatlipoca.

Some groups, such as those from Tlaxcala, held that Mixcoatl was a son of dual god Ometeotl. In this version of Aztec cosmogony, Mixcoatl replaced Xipe Totec as the first of the primordial creator gods’ four children.[5]

Mixcoatl fathered Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl (also known as Ce-Acatl or One-Reed) with the goddess Chimalma.[6]

Family Tree

Mythology

It is easy to think of the Aztec religion as a single monolithic entity. As with religions today, however, Aztec beliefs were complex and heterogenous. The various belief systems at play within the Aztec empire meant that multiple, contradictory mythologies existed as well.

Variously, Mixcoatl was one of the four children of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, a transformed version of Tezcatlipoca, a divinely transformed hunter named Mimich, and a celestial creation of Tezcatlipoca.

Mimich and the Deer-Women

A Nahua legend held that a pair of hunters, Mimich and Xiuhnel, were out hunting one day when they spotted a pair of two-headed deer. The pair chased the deer all day but were unable to catch them. The two hunters stopped to rest for the night, and before too long they found themselves joined by a pair of beautiful women.

Unable to resist the temptation laid before him, Xiuhnel made love to one of the deer-women and was killed by her immediately thereafter. Scared for his life, Mimich started a fire and ran off into the night. The other deer woman, Itzpapalotl, pursued him.

Mimich was ultimately saved by divine intervention when a barrel cactus fell from the sky and pinned Itzpapalotl to the ground. Mimich led the Fire Lords to her and set her body ablaze, revealing four flints in the process. Mimich took the white flint, which contained Itzpapalotl’s soul, and was immediately transformed. Henceforth, Mimich would be known as Mixcoatl, the great warrior-hunter.[7]

This Huastec warrior statue (c. 1440-1521) likely represents Mixcoatl. The figure wears a necklace of human hearts and a belt of skulls.

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0The inclusion of fire in this tale was significant. Much like the Greek Prometheus, who gave fire to humanity, Mixcoatl gave the Nahua people the bow drill, an instrument used to create fire.

An alternative version of this myth held that there were three hunters: Mimich, Ximbel, and Mixcoatl (going by the name of Camasale/Camaxtli).

In this version, the three captured the two-headed deer and Mixcoatl went on a warpath, defeating all who stood in his way. Mixcoatl’s rampage ultimately came to an end when his deer—the source of all his victories—was taken from him. Not all was lost, however. Though Mixcoatl lost the deer, he soon gained a son; the deer had been stolen while he was conceiving Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl in a field with the goddess Chimalma.[8]

Tezcatlipoca and the Milky Way

The Aztecs divided their concept of time into five ages, each ruled over by a different sun. The fourth age came to a violent end when the sun, Chalchiuhtlicue, cried tears of blood for 52 years. In the midst of this destruction, Chalchiuhtlicue inadvertently destroyed the heavens. In the aftermath, Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl put the sky back up. Not content to simply recreate the skies as they had been before, Tezcatlipoca created the Milky Way, which he then turned into the god Mixcoatl.[9]

No story in Aztec mythology is definitive canon, and this tale was no exception. The Codex Ramirez explained that after Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca raised the heavens, they “walked through it, and made the road [the Milky Way] which we now see there.” In this version, soon after the heavens were returned to the sky, Tezcatlipoca “altered his name, and changed himself into Mixcoatl.”[10]

Mixcoatl-Camaxtli as seen in the Tovar Codex (c. 1585).

John Carter Brown LibraryPublic DomainParallels between Mixcoatl and Huitzilopochtli

Huitzilopochtli held a special place in the hearts of the rulers of the Aztec Empire. While the empire itself was geographically and religiously diverse, the capital was founded by the Mexica people. Huitzilopochtli was the patron god of these people and was regarded as the literal founder of the city.

While the Aztec religion regarded Mixcoatl as a god, the 16th-century Spanish historian Bernardino de Sahagun (1499-1590) wrote that “the Chichimecs [the ethnic group inhabiting Tlaxcala] worshipped only one god, called Mixcoatl.” Just as Huitzilopochtli had led the Mexica people to Tenochtitlan, Mixcoatl had led his people to Tlaxcala and was regarded as the most important of their gods.[11]

Made by the people of Eastern Nahua, this earthenware ceremonial drinking vessel (c. 1300–1521) features crossed arrows and feet decorated like eagles—traditional symbols of Mixcoatl.

Museum of Fine Arts, BostonPublic DomainThe power of Mixcoatl’s cult may have been connected to Tlaxcala’s independence from the Aztec Empire. Though the two states battled each other throughout the 1400s, the nature of their combat was highly ritualized and ceremonial. When the Spanish arrived in the New World, they initially fought against the Tlaxcalans; these two sides would later put aside their differences to defeat the Aztec Empire.[12]

Pop Culture

Mixcoatl’s modern legacy is particularly strong in the scientific community. Several species of Central American amphibians and snakes have been named after him, including Pseudoeurycea mixcoatl, Mixcoatlus barbouri, and Mixcoatlus browni.

The ASCII-based 1987 video game NetHack featured Mixcoatl as the “neutral god of the Archeologist pantheon.”