Minyades

A Minyad Displaying the Body of Hippasus by Étienne Barthélémy Garnier (ca. 1800)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOverview

The Minyades—named Alcathoe, Arsippe, and Leucippe—were the three daughters of Minyas, the king of Orchomenus and the ancestor of the Minyans. They made the disastrous mistake of neglecting the rites of Dionysus, preferring to stay at home with their weaving instead of worshipping the god in the hills. As punishment, they were turned into birds or bats.

What were the names of the Minyades?

Ancient sources seemed to agree that there were three Minyades, though they did not always agree on their names.

In what was probably the earliest tradition, the daughters were named Alcathoe, Arsippe, and Leucippe. But in later texts, Alcathoe was sometimes called Alcithoe, Arsippe was sometimes called Arsinoe, and Leusippe was sometimes called Leuconoe.

The Daughters of Minyas by Jean Lepautre (1676)

National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., United States)CC0What did the Minyades do instead of worshipping Dionysus?

As dutiful and hard-working women, the Minyades’ values were at odds with the wild and irrational worship of Dionysus. When the other women of Orchomenus left their homes to observe the god’s ecstatic rites, they instead chose to stay at home and work on their weaving.

The Minyades also made the mistake of scornfully mocking those who participated in Dionysus’ rites, criticizing these other women for abandoning their household duties and behaving inappropriately. This attitude angered Dionysus, who promptly punished the sisters.

The Dance of the Bacchantes by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre (1849)

Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, LausannePublic DomainThe Metamorphosis of the Minyades

The Minyades are best remembered for neglecting the rites of Dionysus by staying home and weaving while the other women went to the hills to observe the god’s ecstatic rites.

Dionysus taught the sisters the error of their ways by causing their looms to be covered up with vines, ivy, or even wild animals. In some versions, he also inspired a mad craving for human flesh in the Minyades that led them to devour one of their own sons. In the end, the Minyades were transformed into birds or bats.

The Dionysus Cup by Exekias (ca. 530 BCE), showing Dionysus sailing in a ship with dolphins

MatthiasKabelCC BY-SA 3.0Attributes

The Minyades were Minyan princesses from the Boeotian city of Orchomenus. They were famous for their industrious natures—though this industry came at the expense of their piety. They were so committed to their work that instead of taking part in the rites of Dionysus, the Minyades preferred to weave at their looms.

The Minyades’ looms were one of their defining attributes. They were also associated with birds or bats—the animals they were transformed into as punishment for their neglect of Dionysus.

Etymology

The term “Minyades” (Greek Μινυάδες, translit. Minyádes)[1] simply means “daughters of Minyas.” This Minyas was the king of Orchomenus in the central Greek region of Boeotia and the eponymous ancestor of the Minyan tribe.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Minyades Μινυάδες (Minyádes) Phonetic

IPA

[muh-NAHY-uh-deez] /məˈnaɪ əˌdiz/

Family

As the designation “Minyades” suggests, the Minyades were the daughters of Minyas, an important early ruler of the Minyans who lived in Orchomenus.

In some accounts, the three sisters were described as unmarried girls or adolescents. However, other sources assigned them husbands and children. The husbands of the Minyades were never named in ancient texts, though Plutarch reports that they were collectively known as Psoloeis (“Soot-Covered Ones”) because of the garb of mourning they donned after the downfall of their wives (the Minyades themselves, in this tradition, acquired the title of Oleiai, “Destroyers”).[6]

The son of Leucippe played a role in some versions of the myth, being torn apart or even devoured by the frenzied Minyades. The boy’s name was sometimes given as Hippasus.[7]

Mythology

The Minyades’ central myth involved their conflict with the god Dionysus. Though there were a few versions of this myth circulating in antiquity, the basic narrative remained the same, with only minor deviations.

In what was probably the earliest known version of the myth, the three Minyades (Lecippe, Arsippe, and Alcathoe) stayed home to weave at their looms while the other women of the city went to the wilderness to observe the ecstatic rites of Dionysus. The Minyades, who were industrious and diligent to a fault, even criticized the other women for abandoning their domestic duties.

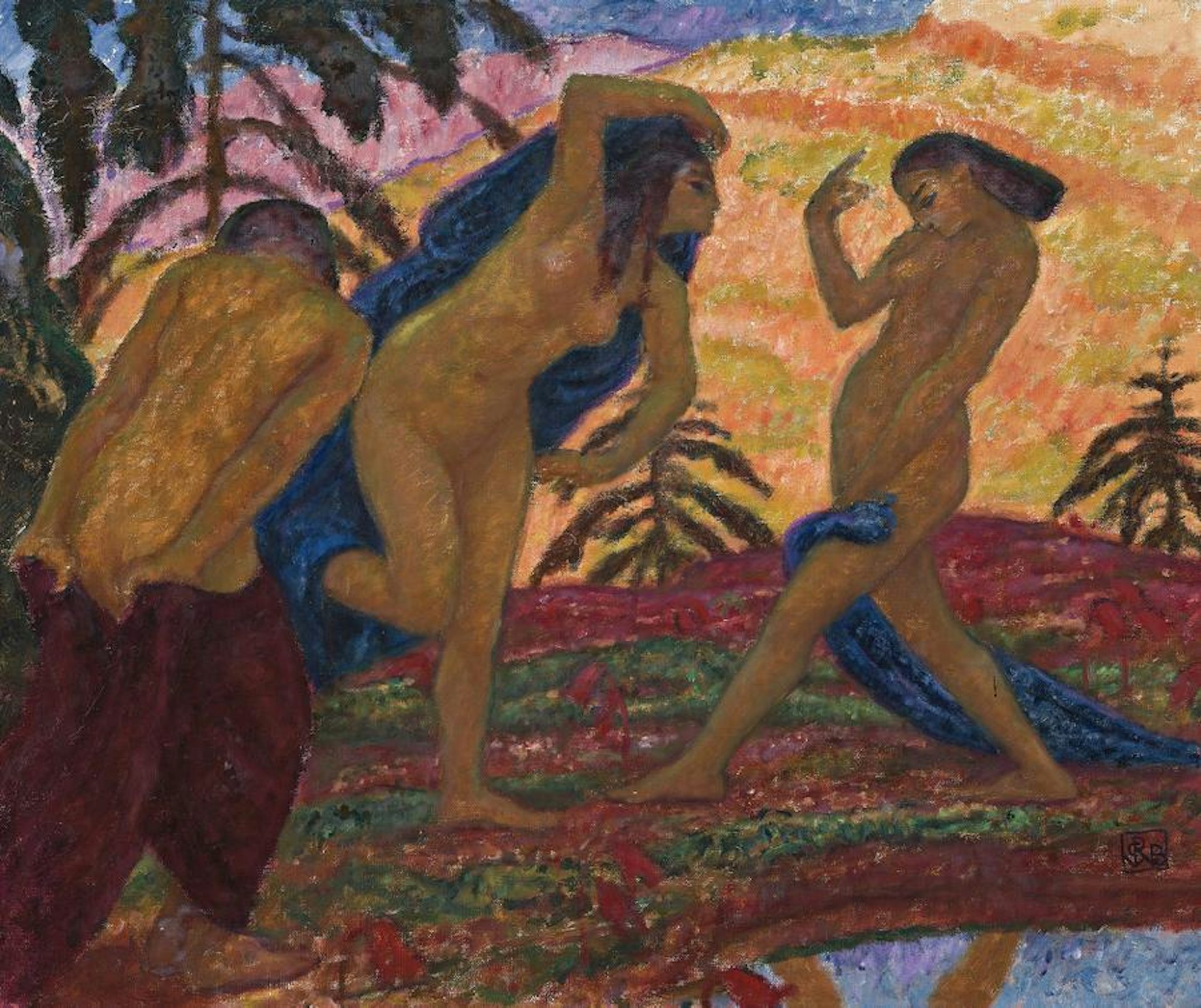

Maenads by Rupert Bunny (between 1913 and 1921)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDionysus approached the Minyades in the guise of a young girl and attempted to impress upon them the importance of giving the gods their due. When this tack failed, Dionysus turned himself into several fearsome animals (a bull, a lion, and a leopard) and caused milk and nectar to flow from the Minyades’ looms.

The Minyades, terrified, decided that one of their children needed to be offered to the god as a sacrifice. They drew lots, and the terrible task fell to Leucippe; the Minyades thus promptly killed Leucippe’s son Hippasus.

Afterwards, they went to the hills to finally join the other women, but it was too late to appease Dionysus: Hermes punished the sisters by turning them into flying animals (a bat and two different kinds of owls).[8]

Ovid, retelling the myth in Book 4 of his Metamorphoses, offered a slightly different account of the Minyades’ punishment. He omitted Dionysus’ appearance and the sacrifice of Leucippe’s son from his version, simply describing how the Minyades’ looms became overgrown with vines before the women themselves were metamorphosed into bats:

Strange to relate! Here ivy first was seen,

Along the distaff crept the wond’rous green.

Then sudden-springing vines began to bloom,

And the soft tendrils curl’d around the loom:

While purple clusters, dangling from on high,

Ting’d the wrought purple with a second die.

[...]

Swift the pale sisters in confusion run.

Their arms were lost in pinions, as they fled,

And subtle films each slender limb o’er-spread.

Their alter’d forms their senses soon reveal’d;

Their forms, how alter’d, darkness still conceal’d.

Close to the roof each, wond’ring, upwards springs,

Born on unknown, transparent, plumeless wings.

They strove for words; their little bodies found

No words, but murmur’d in a fainting sound.

In towns, not woods, the sooty bats delight,

And, never, ’till the dusk, begin their flight;

’Till Vesper rises with his ev’ning flame;

From whom the Romans have deriv’d their name.[9]

In other versions, the Minyades’ motivations were slightly different. There was one tradition in which the sisters developed a mad desire to taste human flesh; it was for this reason that they drew lots and killed Leucippe’s son Hippasus.[10]

Roman sarcophagus showing the triumph of Dionysus (ca. 190 CE)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0In another tradition, the Minyades failed to join the other women in their festivities not because they preferred to weave but because they did not wish to leave their husbands. The vines, ivy, and even snakes with which Dionysus covered their looms did not deter them, so the god finally drove them into a mad frenzy, which ended with them tearing Leucippe’s son apart.

When the Minyades at last tried to join the rites of Dionysus, the other women turned them away. In the end, they were transformed into a bat, an owl, and a crow.[11]

Worship

The myth of the Minyades was the motivation behind the Agrionia, a festival celebrated at Orchomenus well into historical times. At this festival, a priest of Dionysus would ritually pursue the descendants of the Minyades (called Oleiai), sword in hand.

One year, however, a priest named Zoilus actually killed one of the women. Zoilus himself died soon after, but all of Orchomenus had been polluted by this crime. The community was only released from their blood guilt when they took the priesthood away from Zoilus’ family.[12]