Meleager

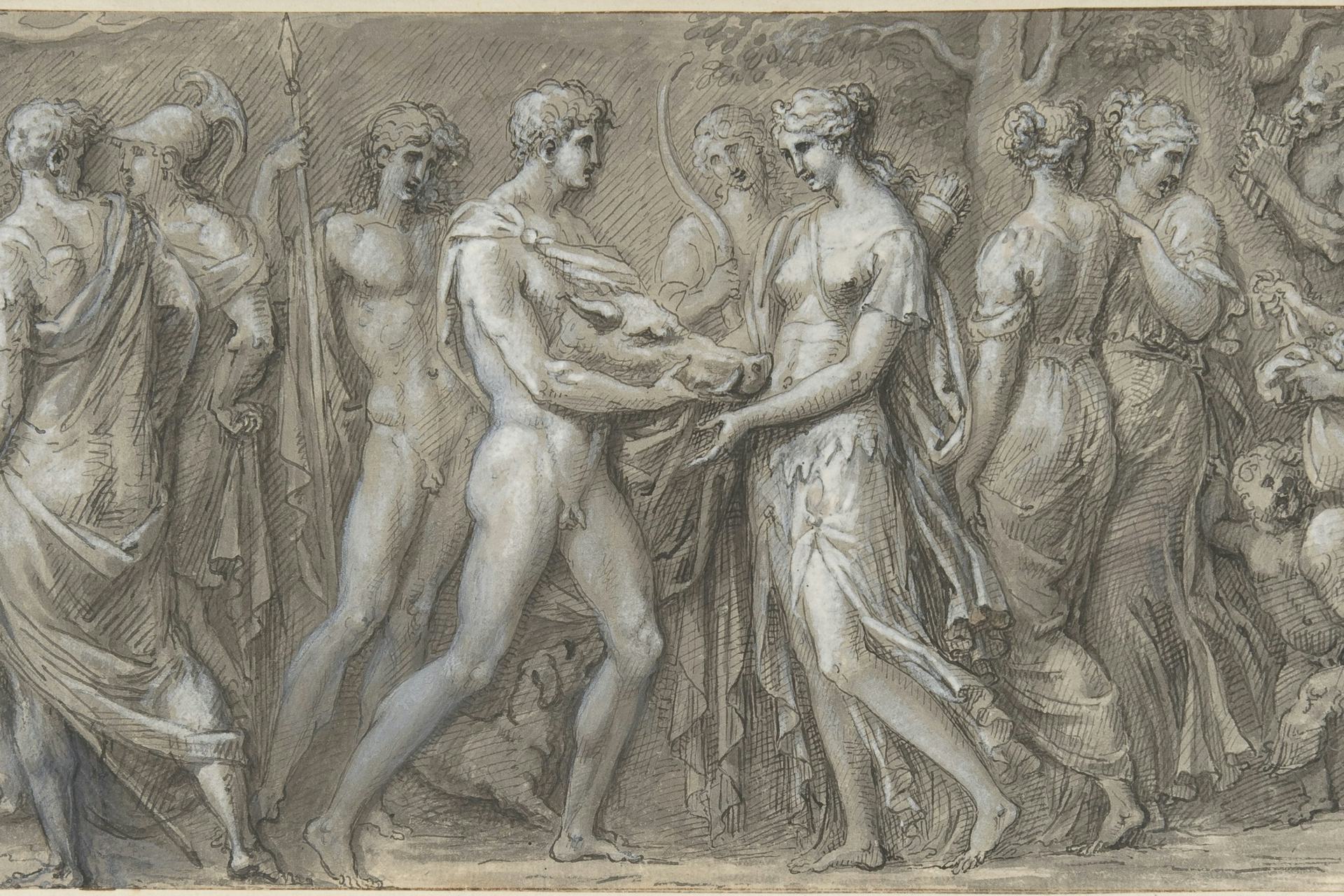

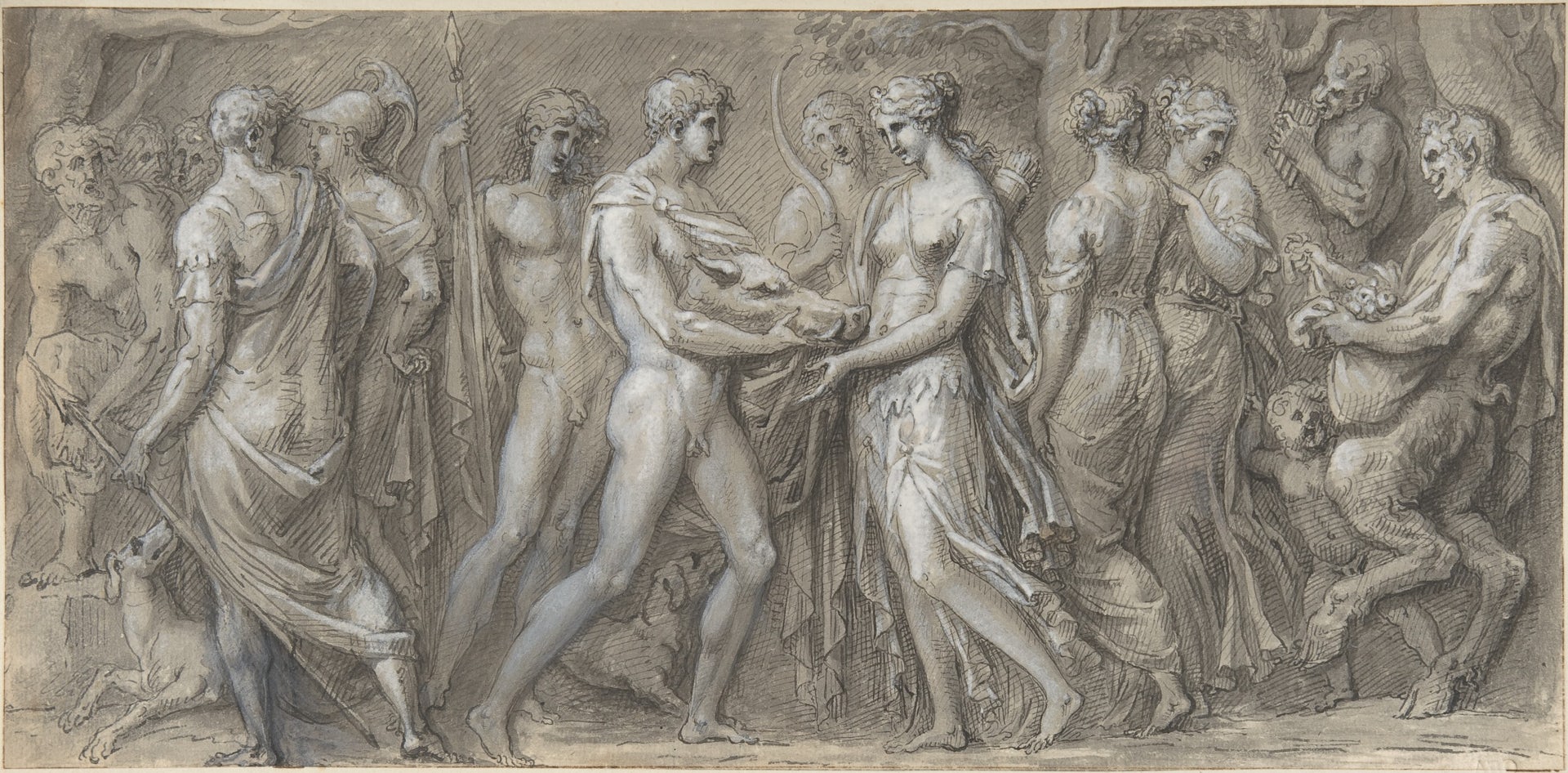

Meleager Presents to Atalanta the Head of the Calydonian Boar by Guillaume Boichot (ca. 1800)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Meleager was a hero and prince from the Aetolian city of Calydon, the son of King Oeneus and his wife Althaea. He took part in several heroic exploits, including the voyage of the Argonauts, though he is best remembered for his role in the Calydonian boar hunt. In the end, Meleager tragically died at the hands of own mother.

According to myth, the goddess Artemis decided to punish Meleager’s father, Oeneus, by sending a giant, vicious beast—later known as the Calydonian boar—to terrorize the city of Calydon. Meleager gathered the greatest heroes of his time to hunt down and kill the creature.

The heroes managed to defeat the boar, but in the aftermath, Meleager quarreled with his uncles over who would receive its hide. He ended up killing them in the ensuing brawl. This enraged Meleager’s mother, Althaea, who retaliated by indirectly causing Meleager’s death.

Whom did Meleager marry?

In most ancient sources, Meleager was married to a woman named Cleopatra. But there was also a well-known tradition in which Meleager fell in love with the heroine Atalanta during the Calydonian boar hunt. Some authorities even claimed that Meleager and Atalanta had a son together.

According to this tradition, it was Meleager’s love of Atalanta that led to his death (albeit indirectly): he tried to give Atalanta the precious hide of the Calydonian boar, but Meleager’s uncles protested, and a brawl ensued. The quarrel ended with Meleager killing his uncles, and Meleager’s mother subsequently killed him in revenge.

Meleager Presents to Atalanta the Head of the Calydonian Boar by Guillaume Boichot (ca. 1800)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHow did Meleager die?

When Meleager was born, the Moirae (also known as the Fates) told Meleager’s mother, Althaea, that her son would die as soon as a certain log in her fireplace had burned away. Althaea immediately removed the log and kept it hidden to protect her son.

Years later, however, Meleager killed his uncles—Althaea’s brothers—in a quarrel over the spoils from the Calydonian boar hunt. When Althaea discovered what Meleager had done, she threw the log into the fire in a fit of rage, causing her own son to die.

Death of Meleager by François Boucher (ca. 1727)

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Calydonian Boar Hunt

According to myth, King Oeneus of Calydon, Meleager’s father, once neglected the worship of Artemis. The goddess punished him by sending a monstrous boar to lay waste to the countryside—the infamous “Calydonian boar.” Determined to protect his people, Meleager led a band of heroes to hunt down and kill the creature.

According to the most common tradition, Meleager fell in love with the heroine Atalanta during the hunt. After the Calydonian boar had been slain, he even wanted to give her the boar’s hide as a reward for having drawn first blood.

Meleager’s uncles (the brothers of Meleager’s mother Althaea) were unhappy with this decision, so Meleager fought and ultimately killed them. This in turn led Althaea to bring about Meleager’s own death (see above).

The Calydonian Boar Hunt by Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1611–1612). The corpse of the fallen Ancaeus can be seen below the boar.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CAPublic DomainEtymology

The etymology of the name “Meleager” (Greek Μελέαγρος, translit. Meleagros) is obscure. It is usually (though not always) thought to consist of two elements.

The first, “mele-,” is likely derived from the Greek verb melein (“to be concerned with, care for”), while the second element may be derived from the Greek noun agra (“hunt”), the Greek noun agros (“cultivated field”), or the Indo-European *ṷagros (“thunderbolt”) and its Indic and Iranian cognates (vájra- and vazra-, respectively, which can denote “healing” and “revivification”).

According to these etymologies, Meleager’s name can be variously interpreted as “he who has a care for the hunt,” “he who has a care for the field,” “he who has a care for the thunderbolt,” or “he who has a care for revivification.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Meleager Μελέαγρος (translit. Meleagros) Phonetic

IPA

[mel-ee-EY-jer] /ˌmɛl iˈeɪ dʒər/

Attributes and Iconography

Meleager hailed from Calydon, a kingdom located in the mountainous region of Aetolia in central Greece. He was the most important son of the Calydonian king and queen and a great warrior, said to have been particularly skilled with the javelin.[3]

Meleager was usually imagined as a handsome and intimidating figure—so intimidating, according to one ancient poet, that even his ghostly shade was enough to strike fear into the heart of the great Heracles when he traveled through the Underworld for his twelfth labor.[4]

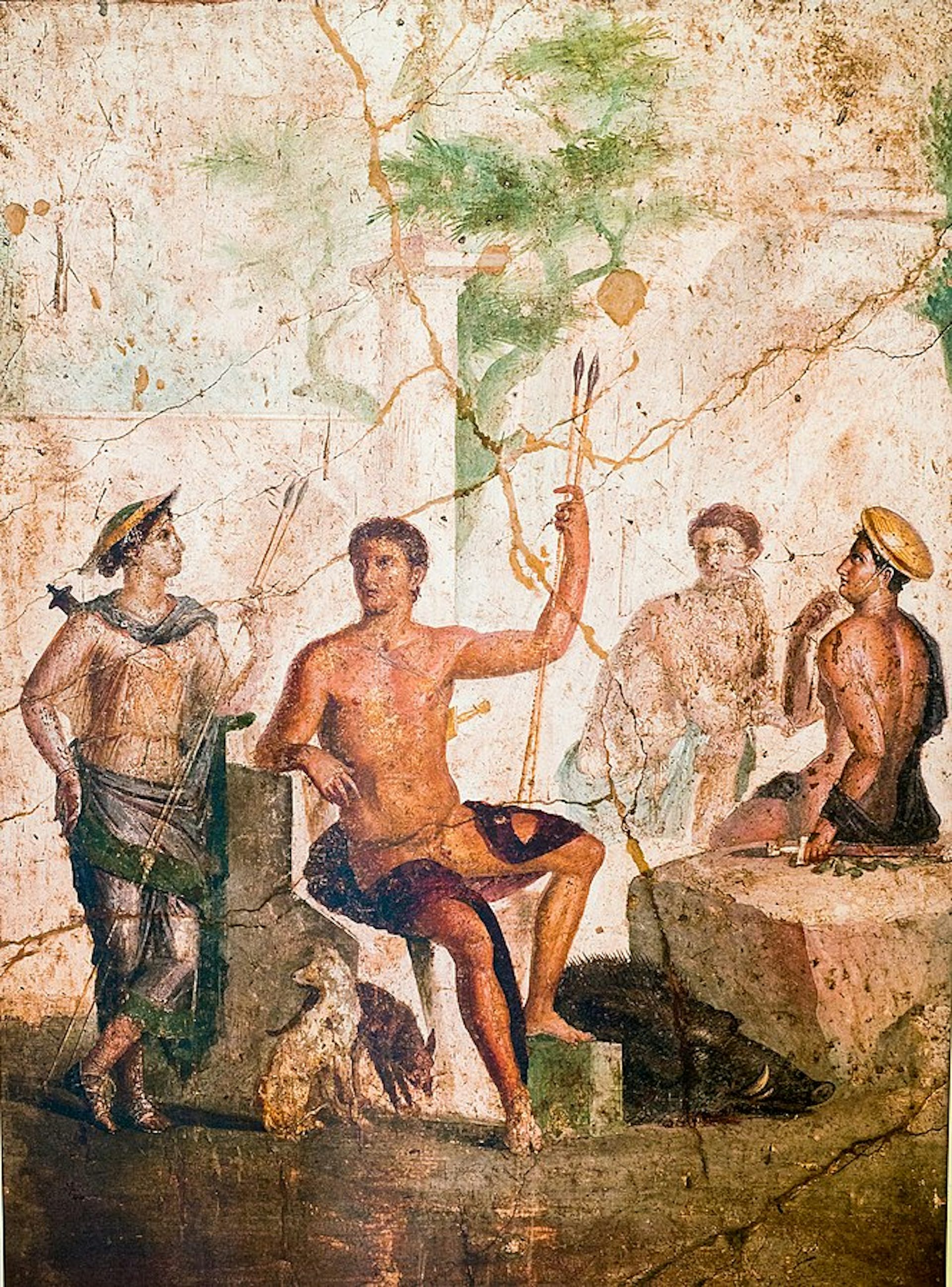

Wall painting from Pompeii showing Meleager holding two javelins and sitting on a rock with Atalanta after the Calydonian Boar Hunt (early-mid 1st century CE). Discovered in the House of the Centaur in Pompeii. National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy.

ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0In the visual arts, Meleager was most often represented in scenes from the Calydonian Boar Hunt (a popular subject from the sixth century BCE on).[5]

Family

Meleager was a prince of Calydon, the son of queen Althaea and either her husband Oeneus or, in some traditions, the war god Ares.[6]

In Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women, Meleager’s siblings are Phereus, Agelaus, Toxeus, Clymenus, Periphas, Gorge, and Deianira;[7] in Apollodorus’ Library, Phereus is replaced with Thyreus, while Agelaus and Periphas are excluded; and in Antoninus Liberalis’ Metamorphoses, the siblings are the same as in Hesiod, but with the addition of two more sisters, Eurymede and Melanippe.[8]

Meleager’s sister Deianira would go on to marry the famous hero Heracles, who thus became Meleager’s brother-in-law.

Meleager’s wife was called either Cleopatra or Alcyone, the daughter of Idas and Marpessa.[9] But in some traditions, Meleager fell in love with Atalanta and even had a son with her named Parthenopaeus (who later became one of the Seven against Thebes).[10] Meleager was also the father of Polydama, sometimes called the wife of the hero Protesilaus, though it is unclear who her mother was supposed to be.[11]

Mythology

Origins and Youth

In what eventually became the best-known version of the myth, the Moirae visited Meleager’s mother, Althaea, soon after Meleager was born. They pointed to a log that was burning in the fireplace and warned that Meleager would only live until that log had been burned away by the fire. Thus, Althaea immediately removed the log and hid it.[12]

The Voyage of the Argonauts

Meleager was one of the Argonauts, the heroes who sailed with Jason on the Argo to steal the Golden Fleece. According to Apollonius of Rhodes, he was still just a boy at the time.[13] In one account, described by Diodorus of Sicily, Meleager killed Aeetes, the king of Colchis, when the Argonauts took the Golden Fleece from him.[14]

The Calydonian Boar Hunt

Meleager is most famous for his role in the Calydonian Boar Hunt. Oeneus, Meleager’s father and the king of Calydon, had offended the goddess Artemis (according to most accounts, he had forgotten her in his sacrifices). To punish him, Artemis sent a huge boar to Calydon (the so-called “Calydonian Boar”) to lay waste to the countryside:

[T]here, his strength raging like a flood, he cut down vine-rows with his tusk, and slaughtered flocks, and whatever mortals came across his path.[15]

The brave Meleager, undaunted, gathered the greatest heroes of his time to hunt down and kill the boar. The list of participants varied across different accounts but usually included such greats as Theseus, the twins Castor and Polydeuces, the brothers Peleus and Telamon, and, of course, the heroine Atalanta.[16] Oeneus promised the boar’s prized hide to whomever killed the beast.

Marble sarcophagus depicting the Calydonian Boar Hunt (3rd century CE).

JastrowPublic DomainIn what eventually became the most familiar tradition, when the heroes tracked down and battled the boar, Atalanta drew first blood, while Meleager delivered the killing blow. Meleager, however, had fallen in love with Atalanta and offered her the boar’s hide, saying that it was hers because she drew first blood.

This led to a quarrel between Meleager and his uncles (named by some authors as Plexippus and Toxeus), who tried to take the hide from Atalanta. Meleager defended her and ended up killing his uncles.[17]

Older versions of the myth, however, offer a very different account. According to Homer and Bacchylides,[18] Artemis caused the Aetolians of Calydon to fight with the neighboring tribe, the Curetes, for the boar’s hide.

In the battle, Meleager killed one or more of his mother’s brothers (traditions vary); according to Bacchylides (who gives the names of the brothers as Iphiclus and Aphares), he did so by accident,[19] but in other accounts he killed them because they were fighting on the side of the Curetes.[20]

Meleager and Atalanta by Jacob Jordaens (1620–1623). Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDeath

There are different versions of Meleager’s death. In what became the most familiar version, Althaea was furious when she learned that Meleager had killed her brothers. She dashed to the spot where she had hidden the fateful log—the same log that, years before, the Moirae had told her was linked to the life of her son—and threw it into the fire. As soon as it was completely consumed by the flames, Meleager died.[21]

However, the Moirae and the log are not mentioned in other versions of Meleager’s death. According to some, Althaea simply cursed him when she found out he had killed her brothers. Hearing this, Meleager withdrew from the war with the Curetes in anger. Without Meleager to help them, the Calydonians suffered heavy losses, but Meleager’s wife, Cleopatra, finally convinced him to rejoin the fighting to defend his people. He returned to battle and helped his people win the day, but was killed in the process because of his mother’s curse.[22]

In one final version, Althaea had nothing to do with Meleager’s death at all. Instead, Meleager was killed by Apollo, who was fighting on the side of the Curetes during their battle against the Aetolians.[23]

After Meleager’s death, some said that Cleopatra and/or Althaea died (or killed themselves) because of their grief.[24] Meleager’s sisters wept so much for their fallen brother that Artemis transformed them into guinea fowl (meleagrides in Greek).[25]

Afterlife: Meleager and Heracles

In one tradition, Heracles met the shade of the dead Meleager when he descended to the Underworld to capture Cerberus (his twelfth labor). The two heroes spoke briefly, and Meleager suggested that Heracles marry his sister Deianira—an arrangement that ultimately proved fatal to Heracles (Deianira inadvertently killed him some years later).[26]

Pop Culture

Meleager has made few appearances in modern pop culture, but he was a recurring character in the 1990s TV series Xena: Warrior Princess, where he was represented as a drunk.