Medea

Overview

Medea was the daughter of Aeetes, who ruled the remote kingdom of Colchis. A descendant of the gods and a priestess of Hecate, Medea was a powerful witch and magician herself. She fell in love with Jason when he came to Colchis with the Argonauts to steal the Golden Fleece from her father. In fact, Medea was so in love that she betrayed her family and abandoned her homeland, helping Jason steal the Golden Fleece and then running away with him to Greece.

Though she was highly devoted, Medea could also be dangerous and overbearing. She went to extreme lengths to help Jason, killing her own brother and later brutally murdering Jason’s uncle Pelias for stealing Jason’s throne. Despite all this, Jason eventually left Medea to marry another woman. Medea used her skills to take revenge on Jason, then journeyed to Athens to marry King Aegeus. But Aegeus soon tired of her as well, and Medea once again had to flee. According to some traditions, she ended up settling somewhere in the steppes of Asia.

Etymology

The name “Medea” (Greek Μήδεια, translit. Mēdeia) comes from the Greek word mēdea, meaning “counsels” or “plots.” It also seems to be related to the Greek medō, meaning “to rule over” or “protect,” and the Proto-Indo-European *med-, meaning “to measure,” “give advice,” or “heal.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Medea Μήδεια (translit. Mēdeia) Phonetic

IPA

[mi-DEE-uh] /mɪˈdi ə/

Titles and Epithets

Medea received a handful of epithets in ancient literature, especially in Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica, an epic that tells the story of the voyage of the Argonauts. Among these epithets are polypharmakos (“she of many drugs”) and doloessa (“crafty”).

Attributes and Iconography

Medea, like most princesses of Greek mythology, was usually depicted as a beautiful woman in both literature and art. But Medea’s most important attribute was her skill as a witch and magician. She was usually associated with Hecate, a goddess of magic—an association that presumably had something to do with her own abilities. Medea always had with her an arsenal of potent potions, herbs, and drugs that allowed her to bend the world to her will.

Medea by William Wetmore Story (1866). High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA.

WmpearlCC0Medea and her awesome powers are vividly described in Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica:

There is a maiden, nurtured in the halls of Aeetes, whom the goddess Hecate taught to handle magic herbs with exceeding skill all that the land and flowing waters produce. With them is quenched the blast of unwearied flame, and at once she stays the course of rivers as they rush roaring on, and checks the stars and the paths of the sacred moon.[1]

Medea was also a descendant of the gods. Her grandfather was Helios, the Titan who personified the sun, and she was the niece of Circe, a minor goddess who was also a powerful magician.

Given her pedigree, it is unsurprising that ancient sources were divided on whether Medea was an ordinary mortal or a divine being. While most authorities—for example, Apollonius of Rhodes in his Argonautica—represented her as a mortal, there were some who did imagine her as a goddess or demigoddess.[2] At the very least, it was usually thought that after her death, Medea went to the Fields of Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed to live in eternal bliss with the other extraordinary mortals and demigods.

In ancient art from the fifth century BCE, Medea was usually shown wearing characteristically Eastern garments and carrying her magical potions. Sometimes she was represented riding the chariot of her grandfather Helios. She was a popular subject in vase painting, statuary, and sarcophagi.[3]

Family

Medea’s father was Aeetes, the king of Colchis and the son of the sun god Helios. In most sources, her mother was Idyia, one of the Oceanids,[4] though some texts gave her mother as Hecate instead.[5] She had two siblings, a sister named Chalciope[6] and a brother named Apsyrtus.[7]

Family Tree

Mythology

Jason

The myth of Medea begins with the arrival of Jason and the Argonauts in Colchis on their quest for the Golden Fleece. The Golden Fleece was in the possession of Aeetes, Medea’s father and the king of Colchis. But Jason’s uncle Pelias, who had unlawfully seized the throne of Iolcus from his brother (and Jason’s father) Aeson, ordered Jason to bring the Golden Fleece to Greece.

Jason recruited the greatest Greek heroes to sail with him to Colchis. Together, they came to be known as the “Argonauts,” after their ship, the Argo. After many misadventures on the high seas, Jason and the Argonauts finally reached Colchis, located on the eastern coast of the Black Sea. But when Jason tried to negotiate with Aeetes for the Golden Fleece, Aeetes was less than gracious: he agreed to hear Jason out only if the young man could yoke his fire-breathing bulls to a plow and sow a field with dragon’s teeth.

Jason would have been quickly killed if he had tried to perform these tasks under ordinary circumstances. Luckily for him, he had caught the eye of Aeetes’ daughter Medea. In most accounts, this actually had nothing to do with luck: the goddess Hera, who favored Jason, knew that Medea alone could help Jason on his mission and so caused her to fall desperately in love with the hero. According to Apollonius of Rhodes, Hera approached Aphrodite, the goddess of love, for help, and Aphrodite in turn sent her son Eros to make Medea fall in love with Jason:

And with swift feet unmarked [Eros] passed the threshold and keenly glanced around; and gliding close by Aeson’s son [Jason] he laid the arrow-notch on the cord in the centre, and drawing wide apart with both hands he shot at Medea; and speechless amazement seized her soul. But the god himself flashed back again from the high-roofed hall, laughing loud; and the bolt burnt deep down in the maiden’s heart like a flame; and ever she kept darting bright glances straight up at Aeson’s son, and within her breast her heart panted fast through anguish, all remembrance left her, and her soul melted with the sweet pain. And as a poor woman heaps dry twigs round a blazing brand … and the flame waxing wondrous great from the small brand consumes all the twigs together; so, coiling round her heart, burnt secretly Love the destroyer; and the hue of her soft cheeks went and came, now pale, now red, in her soul’s distraction.[15]

Medea, overcome with love, sent word for Jason to meet her in secret. She then promised that she would help him, but only if he agreed to take her back to Greece and make her his wife. When Jason accepted these terms, Medea gave him an ointment that would protect him from the bulls’ fire. She also warned him that after he sowed the dragon’s teeth, a race of warriors would sprout from the earth, and that the only way to beat them would be to trick them into killing each other.

Jason did as Medea instructed. With Medea’s ointment, he was able to safely yoke Aeetes’ bulls and use them to sow the dragon’s teeth. Then, when fully armed warriors sprouted from the earth, Jason threw a stone into their midst. The warriors did not realize where the stone had come from and fought among themselves until they were all dead.[16]

Even though Jason had accomplished his assigned tasks, Aeetes refused to hand over the Golden Fleece. Again, Medea was helpful. She led Jason to where Aeetes kept the Golden Fleece—in a secluded grove guarded by a giant serpent. Using magical herbs, she lulled the serpent to sleep while Jason grabbed the Golden Fleece. The two then joined the other Argonauts and sailed away from Colchis.[17]

Escape from Colchis

Apsyrtus

Aeetes soon realized that he had been betrayed and wasted no time in pursuing the Argonauts. He almost caught them, too—but Medea devised a gruesome plan to distract her father by murdering his son (and her brother) Apsyrtus.

In one version, Medea took Apsyrtus with her when she left with the Argonauts, then killed him, cut up his body, and threw the pieces into the sea. Aeetes’ men were slowed down as they stopped to collect the pieces of the boy’s body, which bought the Argonauts enough time to make their getaway.[18]

In another version, it was Apsyrtus who led the Colchians in their pursuit of Jason and Medea. Knowing that Apsyrtus would catch them eventually, Medea lured him onto a small island. She then distracted him while Jason snuck up on him and killed him.[19]

Circe

After they had put some distance between themselves and Aeetes, the Argonauts were tossed about by terrible storms. These storms, they learned, had been sent by the gods, who were angry at them for murdering Apsyrtus. Thus, the Argonauts sailed to the island of Medea’s aunt Circe, a minor goddess and powerful sorceress, to be purified of their blood-guilt.[20]

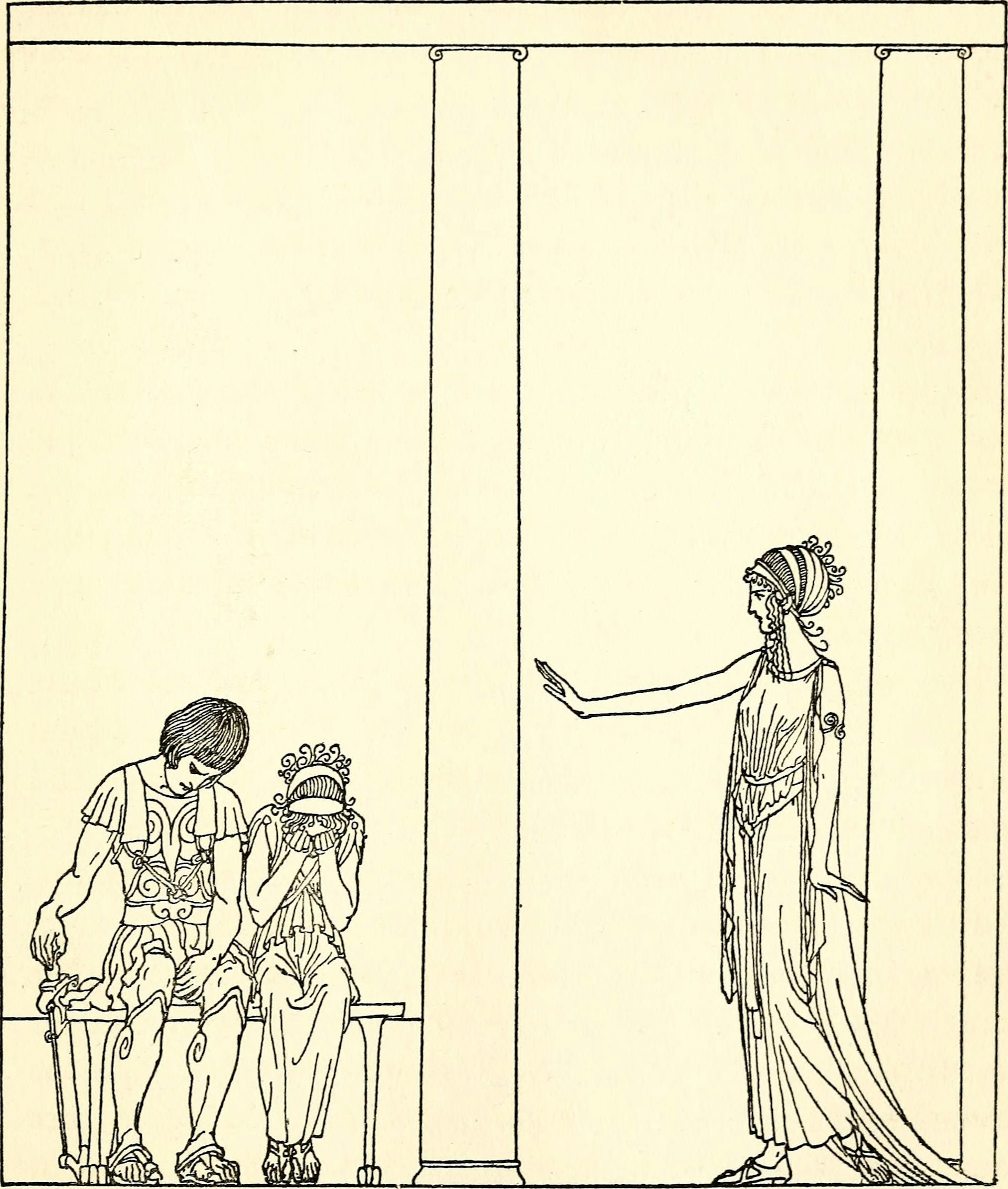

Illustration of Medea and Jason seeking purification from Circe. Drawn by Willy Pogány for Padraic Colum's The Golden Fleece and the Heroes Who Lived Before Achilles (1920).

FlickrPublic DomainThe Island of the Phaeacians

After further adventures, including an encounter with the dangerous Sirens, the Argonauts put in at the island of the Phaecians. The Phaecians were ruled by Alcinous and his wife Arete. It was here that the Colchians finally caught up to the Argonauts.

But Jason and Medea were able to dodge Aeetes once again. Arete hastily and secretly married the young lovers. Alcinous then refused to send Medea back to Aeetes on the grounds that she was already married. The Colchians were unable to do anything more, and the Argonauts sailed away.[21]

Talos

The Argonauts’ final struggle was their encounter with Talos, the giant guardian of Crete. Made of solid bronze, Talos’ only vulnerability was a single vein that ran from his neck to his ankle. Talos would have smashed the Argo and its crew had it not been for Medea. In the common tradition, Medea enchanted Talos and caused him to graze his ankle on a rock so that he cut his vein and bled to death.[22]

The Murder of Pelias

Once the Argonauts were back in Greece, Jason and Medea returned to Jason’s ancestral kingdom of Iolcus. There, they immediately began plotting against Jason’s uncle Pelias—the usurper of Iolcus and the person who had sent Jason to steal the Golden Fleece in the first place.

The details of the myth differ somewhat across the various traditions, but the result is always the same: Pelias was murdered by Medea.

As the story goes, Medea managed to convince Pelias and his daughters that she could restore the aging king’s youth.[23] As proof, she put on a demonstration. She selected an old sheep, cut it up into pieces, and boiled it in a cauldron with magical herbs. A young lamb leapt out. Eager to obtain the same results, Pelias’ daughters immediately cut up their father and tossed him into the cauldron. But Medea did not add the magical herbs, and so Pelias died.[24]

This act horrified the people of Iolcus, who were terrified of Medea’s power. She and Jason were thus exiled and fled to Corinth.

Jason’s Treachery

Jason and Medea lived as husband and wife for several years and had a number of children together (the exact number varies according to the source). But eventually Jason decided to leave Medea for a younger woman: the daughter of the king of Corinth.

Furious at being spurned after all she had done for Jason, Medea carried out a terrible revenge. She sent a poisoned robe to Jason’s new bride, which burned her alive as soon as she put it on. When her father tried to help her, he was burned with her.[25]

In the most familiar version, Medea was not satisfied even after Jason’s bride was dead. Wanting to hurt her wayward husband even more, she also murdered the children she had by Jason.[26] But in another (probably older) version, Medea simply abandoned her children, and they were murdered by the Corinthians as revenge for Medea’s actions.[27]

Medea about to Kill her Children by Eugène Delacroix (1862). Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAs Jason and the Corinthians grappled with what Medea had done, she made her escape. Her grandfather Helios sent her a chariot drawn by flying dragons; Medea got into the chariot and flew away.

Athens, Aegeus, and Theseus

After running away from Corinth, Medea came to Athens.[28] There, she married the king, Aegeus, who had been fighting a dynastic war for many years and who still had no heirs. With Medea, Aegeus finally had a son.

One day, a stranger came to Athens. Though Aegeus did not recognize him, Medea knew that this was Theseus, the son Aegeus had conceived with the Troezenian princess Aethra. Fearing that Aegeus would make Theseus his heir instead of her son, Medea tried to trick Aegeus into killing him.

In one version, Medea had Aegeus send Theseus against the monstrous Bull of Marathon, hoping the bull would gore him to death. But the brave and strong Theseus succeeded in killing the bull, thus foiling Medea’s plan.[29]

In another version, Medea told Aegeus that Theseus was a threat, then poisoned his food. But just as Theseus was about to consume the poison, Aegeus recognized him by the sword he was carrying: it was his own sword, which he had left with Aethra at Troezen. He immediately stopped Theseus from taking the poison.[30]

After Aegeus recognized Theseus as his son, Medea again fell out of favor. She went into exile for the last time.

Medea in the East

What happened to Medea after that is obscure. In some accounts, she took Medus (usually said to have been her son by Aegeus) to the Asian steppes. There, Medus became a great conqueror and founded a kingdom, which he named Media after himself and his mother.[31]

In another account, Medea went back to Colchis. There, she learned that her father Aeetes had been deposed by his brother Perses. Medea (or Medus, in some versions) killed Perses and restored Aeetes to the throne.[32]

Other Myths

There are a handful of other scattered myths about Medea.

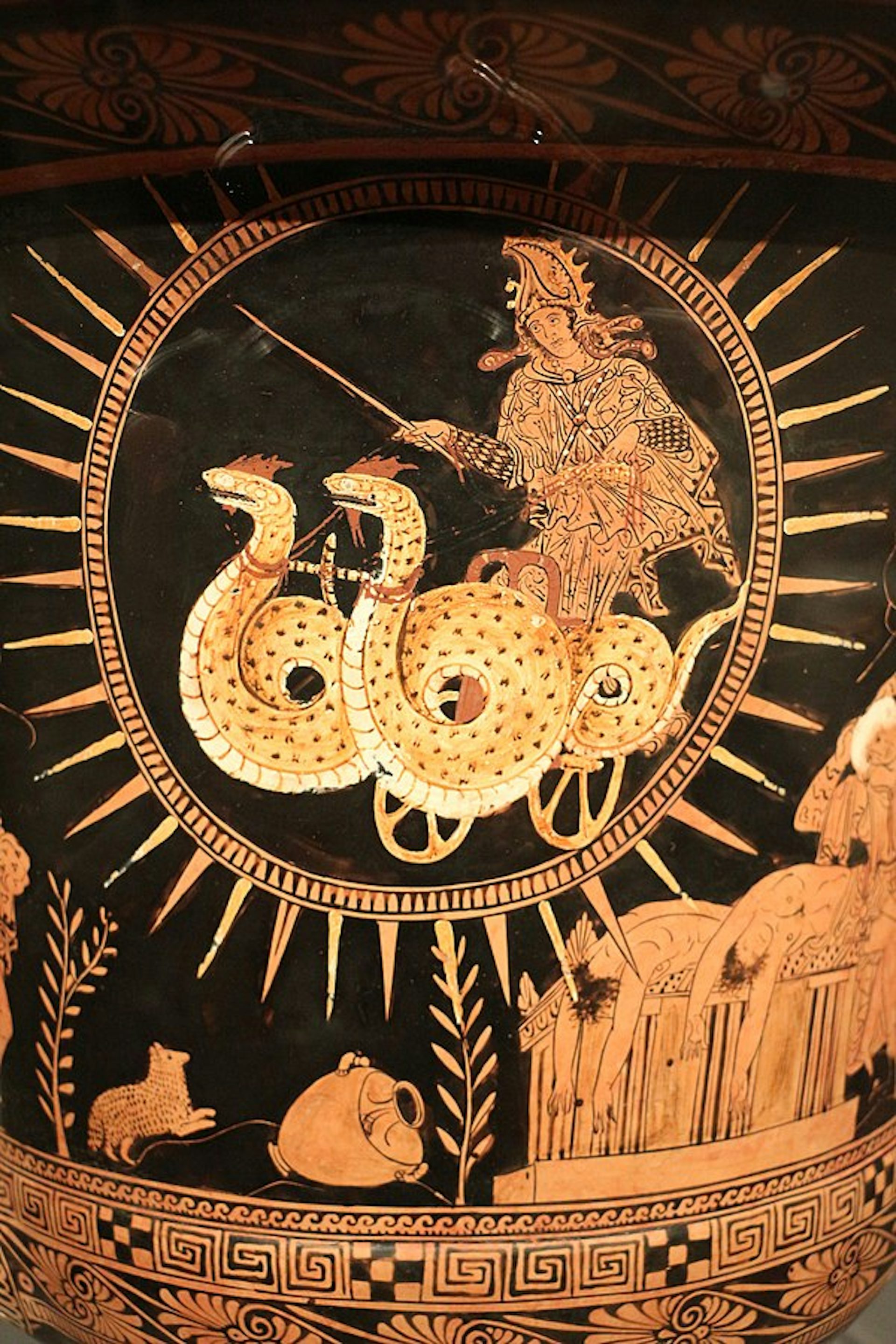

Red-figure calyx showing Medea fleeing Corinth on a chariot drawn by flying dragons. Attributed to the Policoro Painter (ca. 400 BCE). Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH.

SailkoCC BY-SA 3.0In one myth, Medea’s wanderings brought her to Italy. There, she taught the Marrubians how to charm snakes. She was subsequently given the honorary name Anguitia or Angitia (anguis is the Latin word for snake).[33]

Another myth also explored Medea’s connection with snakes. This time, Medea is said to have stopped at Absorus, a town on the eastern coast of the Black Sea where her brother Apsyrtus had been buried. The town was overrun with snakes, so Medea used her abilities to gather them and put them in Apsyrtus’ tomb.[34]

In yet another myth, Medea wound up in Thessaly, where she entered a beauty contest with the Nereid Thetis, Achilles’ mother. The contest was decided by the Cretan hero Idomeneus, who judged it in Thetis’ favor. Medea accused Idomeneus of lying and laid a curse on him, making him incapable of ever telling the truth.[35]

Eventually, Medea became a goddess and lived eternally among the greatest figures of Greek mythology in Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed. Some say she married Achilles, the most famous of the heroes who fought in the Trojan War.[36]

Worship

Medea was sometimes regarded as a goddess, though there is little evidence for her worship in the ancient Greek world. She did have some indirect presence in Corinthian cult, however. The Corinthians would perform annual rituals to expiate the murder of Medea’s children (this supported the version of the myth that said the Corinthians, rather than Medea, were responsible for killing the children). Seven boys and seven girls would be dressed in black and have their hair cut. They would then spend one year living in the Temple of Hera Acraea (“Hera of the Heights”), where the Corinthians believed Medea’s children had met their end.[37]

Pop Culture

Medea has made numerous appearances in modern pop culture.

In literature, she has inspired a number of novels, including H. M. Hoover’s The Dawn Palace: The Story of Medea (1988), Percival Everett’s For Her Dark Skin (1990), and Christa Wolf’s Medea (1993). She has also featured in plays by Peter Kien and A. R. Gurney.

In visual media, Medea is perhaps best known from the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts or the 2000 Hallmark miniseries of the same name. But Medea has been depicted in many other films and television shows as well.

Finally, Medea has also featured in video games, including Rise of the Argonauts and Fate/Grand Order.