Krishna

Overview

Krishna is the archetypal trickster. As an avatar of Vishnu, he straddles the line between god and man, embodying both a mischievous adolescent as well as the supreme godhead who encourages Arjuna to fight in the Bhagavad Gita. While he was undoubtedly a fiercely strong warrior, most of his exploits were accomplished through trickery.

Krishna has worn many guises: chief protector of his clan, lover of Radha, husband of over 16,000 wives, and the supreme god who amazed his mother with a vision of the entire cosmos within his mouth.

Etymology

According to Monier Monier-Williams, the Sanskrit kr̥ṣṇa can mean simply “dark, darkish, blue, black.” For this reason, depictions of Krishna show him with blue or darkened skin, similar to Rama and other Vishnu avatars. Kr̥ṣṇa also describes “the dark half of the lunar month from full to new moon.”[1]

Pronunciation

English

Sanskrit

Krishna or Kr̥ṣṇa कृष्ण Phonetic

IPA

[Krish-nuh] /kr̥ɪʂɳɐ/

Titles and Epithets

Attributes

Krishna’s most recognizable weapon is the Sudarshana Chakra, a magical discus that returns to his hand after being thrown. This weapon, along with his blue or dark skin, emphasizes his connection with Vishnu.

Domains

As a semi-divine playboy, Krishna is well known for his erotic exploits and trickery. He embodies the concept of lila, or playful sport. He is also famous for his acts of strength and for slaying demons—somewhat comparable to the Greek hero Heracles.

Family

Krishna’s family ties are more complicated than those of other gods, as he is the biological son of Vasudeva and Devaki but was raised by Nanda and Yashoda in a small cowherding village. His brother, Balarama, remained a constant companion throughout his adventures, and his 16,000 marriages led to thousands of children.

Family Tree

Parents

Fathers

Mothers

- Vasudeva

- Nanda

- Devaki

- Yashoda

Siblings

Brother

Sister

- Balarama

- Subhadra

Consorts

Wives

Lovers

- Rukmini

- Satyabhama

- Kalindi

- Mitravinda

- Satya

- Rohini

- Lakshmana

- Radha

- Gopis

Children

Daughter

Sons

- Charumati

- Pradyumna

- Charudeshna

- Sudeshna

- Charudeha

- Charugupta

- Bhadracharu

Mythology

Origins

The cult of Krishna in the form of Vasudeva can be confidently dated back to antiquity, with evidence of his worship appearing in inscriptions and on coinage from that era.

The earliest record of Krishna appears on the Heliodoros pillar, a stone column named for an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialkidas. The pillar is notable for its image of Garuda, the mount of Vishnu, and features an inscription written in a northwestern Prakrit with some Sanskritic elements. Cross-referencing Antialkidas and the inscription’s writing style gives scholars a solid footing for dating Krishna’s worship (or that of a precursor to Krishna) to at least the late second century BCE.[5]

Furthermore, a coin of the Indo-Greek king Agathocles (early second century BCE) bears an image of Balarama on the obverse and Vasudeva on the reverse, showing that the cult of these heroes not only existed at that time but was also popular enough to be included on royal coinage.

However, Wendy Doniger notes that Krishna’s development from local cult-hero to avatar of Vishnu took centuries:

[Krishna is] (like Rāma) a mortal warrior, but merely one among many, and his identification with Viṣṇu only begins to take place in the latest parts of the Epic. The myth of the child Kr̥ṣṇa is only dimly foreshadowed in Vedic and Epic texts, though it may have been a very old folk legend in the non-Sanskrit tradition (as yet unconnected with the god Viṣṇu), and this part of the Kr̥ṣṇa cycle is first told in full in the Harivaṃśa, the Purāṇic appendage to the Mahābhārata.[6]

Cornelia Dimmit and J. A. B. van Buitenen likewise consider Krishna’s status as an avatar of Vishnu to be a later development, saying,

It appears likely that he was first an independent deity, or hero, who was eventually absorbed by Viṣṇu as supreme god. In this way Viṣṇu acquired for himself a number of epithets derived from Kr̥ṣṇa’s exploits. Among these are Govinda, “cow-finder”; Dāmodara, “rope-belly”; Keśava, “fine-hair”; and the like.[7]

They also identify notable differences in the depiction of Krishna’s divinity across the Puranas, the Mahabharata, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Harivamsa. In the Mahabharata, for example, Krishna is a semi-historical figure and folk hero, the ruler of Dvaraka and “a human hero in the process of becoming a god.” It is only within the Bhagavad Gita, a shorter text absorbed into the Mahabharata, that Krishna claims to be the supreme godhead.

The epic, heroic, and human figure of Krishna largely disappears from the Puranas, replaced by a fully divine figure closer to his depiction in the Bhagavad Gita. This version of Krishna as divine is “utterly different from Kr̥ṣṇa’s exploits in the [Mahabharata].” Dimmit and van Buitenen go so far as to say that “Kr̥ṣṇa the divine child and Kr̥ṣṇa the epic hero appear to be two distinct and separate personalities, one human, one divine. If they have anything in common, it is a tendency to trickery and deceit, but always, presumably, in the service of the good.”[8]

Birth

Krishna proved himself a trickster before he was even born. The evil king Kamsa of Mathura once learned of a prophecy that his cousin Devaki and her husband Vasudeva would bear a child who would one day end his life. Instead of killing her, Kamsa kept watch over her and Vasudeva day and night. Whenever she bore a child, he immediately killed it by smashing it against the ground. Devaki’s first six children all died this way.

The seventh child appeared to be a miscarriage, but in fact the goddess Sleep took the infant away while it was still in the womb and implanted it in the womb of Vasudeva’s other wife, Rohini. This child would grow up to be Balarama, Krishna’s older brother. All of this happened as Vishnu had foreseen, for he had made plans to be born in Devaki’s womb in order to slay Kamsa at the appropriate time.

Vishnu now came down into Devaki’s womb and awaited his birth. But before being born, he arranged for the goddess Sleep to be conceived in the womb of Yashoda, the wife of Vasudeva’s cousin Nanda. When the time came, the two were born on the same night. Vasudeva whisked the newborn Krishna away and delivered him to Yashoda, then took the goddess Sleep and gave her to Devaki, thus swapping the infants.

When Kasma discovered a baby in Devaki’s chamber, he smashed it against the ground, killing the goddess Sleep instantly but leaving Krishna safe from Kamsa’s clutches. For her help, Sleep rose to heaven as an even more frightening and awe-inspiring goddess.

Childhood

Killing the Demoness Putana

When Krishna was still a baby in his cradle, the demoness Putana wandered from village to village looking for children to swallow. With her magic, she disguised herself so that she appeared beautiful, with well-made clothes, jasmine flowers tied in her hair, and a lotus in her hand.

One day she came upon Krishna’s village, and his mother, Yashoda, let Putana hold the baby and breastfeed him with her poisoned breasts. But even as a baby, Krishna knew her to be a demoness, so he drank so deeply that he drew out her life’s breath and drained her of her vital organs. The poison, moreover, had no effect on him. As her lifeless body fell, the magical disguise disappeared, and everyone nearby saw her hideous demonic form.

Yet when the villagers burned her body on a pyre, the smoke was sweet and clean: Krishna’s act had cleansed Putana of her wickedness. Following her death, she rose up to heaven as a reward for giving Krishna her breast milk, poisoned though it was.

Stealing Butter and the Cosmic Vision

By all accounts, Krishna was a little terror to his village as a child. His mother, Yashoda, shrugged off the stories that the women of the village told her: that he played pranks of all kinds, stole food and butter, let out the cows when they should be tied up, and broke pots or poked holes in them to get at what was inside. Since he was always kind and behaved himself around her, she would not believe such things.

But one day, she heard that Krishna had eaten dirt and confronted him. After looking inside his mouth to learn the truth, she was treated to a cosmic vision:

She then saw in his mouth the whole eternal universe, and heaven, and the regions of the sky, and the orb of the earth with its mountains, islands, and oceans; she saw the wind, and lightning, and the moon and stars, and the zodiac; and water and fire and air and space itself; she saw the vacillating senses, the mind, the elements, and the three strands of matter. She saw within the body of her son, in his gaping mouth, the whole universe in all its variety, with all the forms of life and time and nature and action and hopes, and her own village, and herself.[9]

In that moment, Yashoda recognized the child as the supreme god, but Krishna soon laid his enchantment upon her, and she forgot all that she had seen.

This tale echoes a similar myth from the Mahabharata in which Markandeya was left floating on the vast ocean after the flooding of the world and the dissolution of the cosmos. He noticed a boy sleeping under a tree and, after entering the boy’s mouth, had a vision of the entire cosmos. The boy was once again none other than Vishnu in disguise.

Adolescence

Defeating the Snake Kaliya

Once, when Krishna and his friends stopped for a drink along the Kalindi River, his friends fell lifeless on the bank owing to the poisonous waters. Long before, the mighty snake Kaliya and his wives had plunged into the river to flee from the semi-divine eagle Garuda, and the waters had been poisonous ever since. “This will not do,” Krishna thought, and a magical rain of ambrosia fell upon his friends, reviving them.

After learning that the water was poisonous, Krishna plunged straightaway into the river to rid the world of Kaliya’s evil. The snake bit him as soon as he saw him, and the two wrestled and thrashed about in the water. The commotion attracted nearby villagers, who joined Krishna’s friends on the shore just in time to see Krishna and the snake break the surface of the water. To their horror, they watched as Kaliya swallowed him whole.

The wives of the many-headed snake Kaliya plead for Krishna's mercy as he stomps on their husband's heads. Villagers and gopis look on, amazed, ca 1785.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe village was wracked with grief, as everyone but Krishna’s brother Balarama thought him dead. But soon Kaliya spat Krishna out, stretched the hoods of his many cobra-like heads, and spat venom at Krishna. In the ensuing fight, Kaliya grew exhausted, and Krishna mounted his heads and danced on them with such force that the snake vomited blood and was nearly crushed to death.

Only the pleading of Kaliya’s wives stopped Krishna from smiting the serpent. Now recognizing Krishna for the supreme godhead, Kaliya and his wives and children agreed to leave the river in peace and dwell in the ocean.

Dalliances and Stealing the Gopis’ Clothing

Upon reaching adolescence, Krishna and his pranks took on a more predatory and erotic nature, especially toward the village gopis (the female cowherds).

Years after Krishna’s defeat of Kaliya, the village girls spent a month worshipping the goddess Katyayani in the hopes that the goddess would grant them Krishna’s affections. Every morning they bathed in the river that Krishna had made safe, made an improvised image of the goddess out of sand, and offered it perfumes and garlands, each of them asking the goddess to make Krishna her husband.

Their hopes were not unfounded: by now Krishna had developed a reputation as a lady’s man and playboy. At night, Krishna went out alone in the woods to play his flute, and the village women, unable to resist his charms, gave up their chores and came out to dance with him in the moonlight. Abandoning their families and husbands for the night, they sported with Krishna and made love. At times, he made magical copies of himself so that he could be with all of them at once, foreshadowing his future marriage to over 16,000 women.

Ivory panel of Krishna and the gopis, ca 17th century.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainTheir passionate devotion to him is a symbol of the often frenzied attraction that devotees feel for the divine, overstepping the bounds of acceptable and proper behavior. The image of Krishna dancing the rasalila[10] dance with the gopis has become a central motif of his life story.

One day, as the girls were playing in the river and praising Krishna as usual, Krishna and his friends snuck up, snatched away their clothes, and climbed a nearby tree. He offered to return their garments, but only if they came out with their hands on their heads—which they did with great shame and modesty.

Love Affair with Radha

Among the gopis, Krishna was infatuated with Radha most of all. Although she was already married, the erotic pull toward Krishna proved unbearable, and their short love affair was feverish. The social norms of dharma and marriage made the affair highly inappropriate. In this way, Krishna stands apart from other avatars of Vishnu: rather than upholding dharma, this trickster figure has a more flexible relationship with right and wrong.

Some traditions see Krishna’s semi-divine status as a justification for his behavior: he is a god, so it is acceptable for him to have affairs under certain circumstances. Other texts have sought to justify his romantic dalliances by connecting all of his wives and lovers to Lakshmi, Vishnu’s divine consort. The Bhagavata Purana, for example, casts Radha as an embodiment of Lakshmi. Likewise, the village gopis and the 16,000 women he later marries share in Lakshmi’s divine essence, making all of these relationships ultimately appropriate.

Regardless, attitudes towards his affair with Radha have varied over time and across different literary and religious traditions. Vaishnava sects have often defended the illicit nature of their relationship, holding up Radha as the ideal devotee.

David Kinsley notes that “the superiority of illicit love [for devotion to Krishna and the godhead] is argued by the Bengal Vaiṣṇava theologians in some detail. Their main point is that illicit love is given freely, makes no legal claims, and as such is selfless … And selfless love is what Kr̥ṣṇa desires.”[11] Thus, Radha’s affair with Krishna serves as a metaphor for the ideal relationship between the human and the divine: frenzied, ecstatic, irresistible, and devastating at the same time.

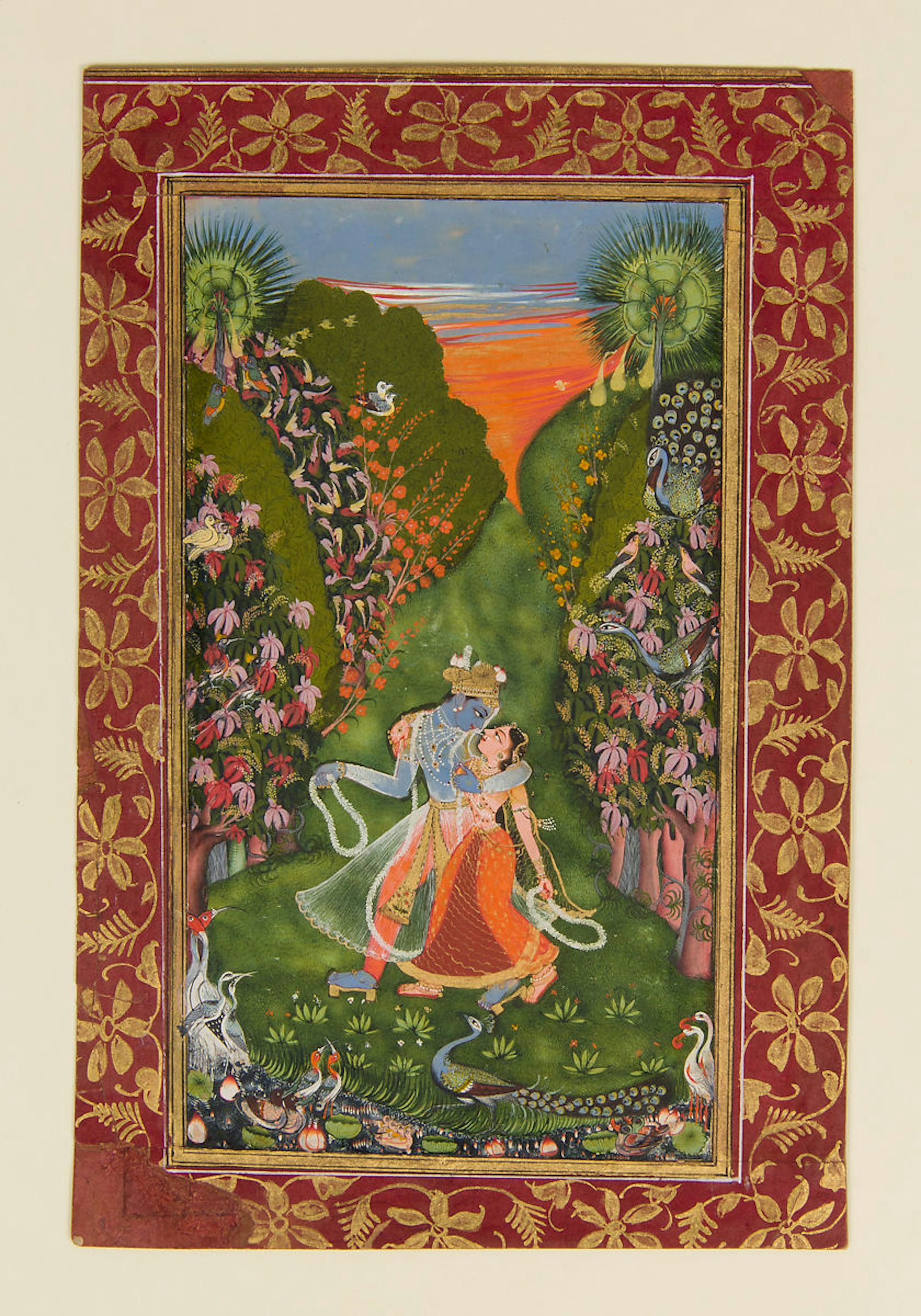

Radha and Krishna flirt in the woods as bright flowers and colorful birds mirror their love, ca. 1750–1775.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOwing to her marriage to someone else, Radha was unable to follow Krishna on his later adventures to Mathura and Dvaraka. Throughout the many poems devoted to their love, she is described as parakīyā, “belonging to another.” The Dashavataracharita (“Deeds of the Ten Avatars”), written by Kshemandra, depicts a distraught Radha weeping uncontrollably when Krishna sets out for Mathura without her:

With tears, flowing away like life in Mādhava’s desertion,

Falling on her breasts’ firm tips, Rādhā was like a laden kadamba tree

As tears were strewn by her endless sighing and trembling gait—

Darkened by the delusion that was bound to all her hopes,

She became like the new rainy season engulfed in darkness.[12]

Krishna matches her grief with his own longing: the Dashavataracharita and Hemachandra’s Siddhahemashabdanusana describe Krishna scanning the horizon and looking longingly for any sign of Radha when he mounts his chariot to leave the village:

Though Hari sees every person with full regard,

Still his glance goes wherever Rādhā is—

Who can arrest eyes ensnared by love?[13]

Adulthood

Wrestling Contest and Slaying Kamsa

By now, Kamsa had learned the truth—Krishna had survived birth and was the child prophesied to kill him. Thus, he resolved to lure both Krishna and Balarama to their doom by means of a wrestling match at an upcoming festival of strength. His champions, Chanura and Mushtika, were undefeated. And if those two could not best the boys, he mused, the great elephant Kuvalayapida would surely trample them to death.

Kamsa’s plan failed spectacularly. At the festival, he challenged competitors to string his mighty bow, confident that none could even lift it, but Krishna managed to pull the string back far enough to break it.[14] The snap could be heard for leagues all around. Before Balarama and Krishna could enter the wrestling arena, the elephant Kuvalaypida charged at them, but the boys snapped off his tusks and used them as weapons to bludgeon the elephant and his handlers to death, as if they were only playing.

Their wrestling opponents fell just as easily: Krishna smashed Chanura onto the ground, splitting him into a hundred pieces, and Balarama pounded Mushtika to death with his fists.

In the chaotic aftermath of these fights, Kamsa attempted to kill the boys, but Krisha leaped onto Kamsa’s platform near the arena and grabbed him by his hair. Krishna then hurled Kamsa to the ground and stomped on him, killing him with the weight of the whole world.

Bodybuilder weight depicting Krishna in battle with a horse demon, ca. 3rd century CE. Krishna's exploits in the wrestling match against Chanura make him an appropriate subject to decorate this weight.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainProtecting the Yadava Clan and Building Dvaraka

With the death of Kamsa, Vishnu had achieved his purpose for being born on earth. Now his task was to lead his clan, the Yadavas of Mathura, as king and protector. To save the Yadavas from their enemies to the east and west, Krishna built the seaport city of Dvaraka and made it an impregnable fortress that any force could defend. But Krishna still preferred to defeat his enemies through trickery whenever able.

When the Yavana king assailed the city, Krishna came out alone and led his opponent on a chase through the surrounding forest. When the king came upon what he thought was a sleeping Krishna, he gave a strong kick. But to his dismay, the figure was none other than Muchukanda, a powerful king from a bygone era who was blessed by the gods with the ability to set on fire anyone who disturbed his rest. Upon waking, Muchukanda smote the Yavana king, killing him in a great pillar of flames.

Wedding with 16,000 Wives

At one time, the demon king Narakasura oppressed the gods. He stole Varuna’s umbrella and the earrings of his own divine mother, Aditi. His city of Pragjyotishapura was considered impregnable, protected by high walls, devious traps, and moats filled with fire, water, and stormy winds. But Krishna was stronger than the walls: he smashed them with his mace, and with his conch he blew a great blast that disheartened all of Narakasura’s warriors.

When the time came for Narakasura to face Krishna, he fell swiftly, beheaded by Krishna’s discus (called Sudarshana). The avatar installed Narakasura’s son Bhagadatta on the throne, set the city of Pragjyotishapura in order, and visited the harem. There he found 16,000 women Narakasura had taken captive after defeating their fathers and kings in war.

Upon seeing Krishna, every single captive was entranced by his looks, charm, and bearing, and each wanted him as her husband. Krishna happily granted their wish. After sending them back to his city of Dvaraka, he married each and every one of them. Not wanting to neglect any of his now considerable number of wives, he multiplied himself so that he could spend time with them all simultaneously.

Role in the Mahabharata

Throughout the Mahabharata, Krishna is often relegated to the role of spectator or adviser to his friend Arjuna, with a few notable exceptions. He convinces Arjuna to abduct his sister, Subhadra, and take her for a wife. Together they burn down Khandava Forest in order to satisfy Agni, the god of fire. Krishna plays the role of ambassador throughout the buildup to the Battle of Kurukshetra and lends his entire army to Duryodhana for the battle, all while serving as Arjuna’s charioteer on the opposing side.

Bhagavad Gita

With the outbreak of the great civil war between the Pandavas and Kauravas for the throne of Hastinapura, many heroes found themselves fighting their own cousins, uncles, and other family members. Krishna’s friend, the mighty warrior Arjuna, grew skittish and wanted no part in the coming battle if it meant harming his family and former teachers. Krishna, however, urged him to fight; their dialogue forms the center of the religious text the Bhagavad Gita.

During their talk, Arjuna asks to see Krishna as he really is—in his fully divine form. Krishna responds with the following verse, echoing an earlier time when Krishna revealed the entire cosmos within his mouth:

haikasthaṃ jagat kṛtsnaṃ paśyādya sacarācaram

mama dehe guḍākeśa yac cānyad draṣṭum icchasi

See, o Gudakesha (Arjuna), the whole world with its moving and non-moving

things all together within my body, and whatever else you want to see.[15]

He continues:

kālo 'smi lokakṣayakṛt pravṛddho;

lokān samāhartum iha pravṛttaḥ

ṛte 'pi tvā na bhaviṣyanti sarve;

ye 'vasthitāḥ pratyanīkeṣu yodhāḥ

I am death, the mighty destroyer of worlds,

Arisen here to annihilate worlds

Even without you, none of the assembled warriors

In the enemy armies will survive.[16]

Here and throughout the dialogue, Krishna stresses the ultimate nature of reality: no one in the battle, whether Pandava or Kaurava, could truly be killed because their atman, or Self, would only move on to their next birth. Arjuna, realizing he could never permanently harm his friends, family members, and teachers, thus summoned the courage to fight in the brutal battle to come.

Death

The Pandavas emerged victorious after a devastating battle that saw millions of casualties. The aftermath was harsh for Krishna as well. Gandhari railed against Krishna for having the ability to stop the battle and choosing not to, and she cursed him to suffer the complete destruction of his clan, the Yadavas.

Her curse came true. Not long after the battle, his clan turned to infighting and destroyed itself from the inside out during a festival, leaving Krishna as the last remaining member. Eventually, he too fell while resting peacefully in a grove. A hunter by the name of Jara saw the sleeping avatar in the grass and mistook him for a deer. He loosed an arrow and struck Krishna in his heel, and the god soon perished.[17]

Worship

Festivals and/or Holidays

Holi

Krishna plays an important role in the well-known festival of Holi, in which celebrators toss brightly colored powders and dyes at each other. Bonfires are lit the evening before the celebration, symbolizing the coming of spring and the victory of light over darkness.

Legends vary regarding the festival’s origins, but a popular myth holds that a young Krishna was too shy to approach Radha owing to the darkness of his skin. His mother told him to paint Radha’s face in whatever color he wanted so that the two would look the same. This undoubtedly appealed to the mischievous avatar, and soon Radha, Krishna, and the other village girls were bestrewn with powders and dyes of all different colors.

Temples

As a popular god in a major world religion, Krishna has temples all around the world, primarily in South and Southeast Asia. More recently, Krishna worship has spread throughout the United States and the countries of the former USSR.

The Dwarkadhish Temple in Gujarat, India commemorates the city that Krisha built to protect the Yadava clan. The Krishna Balaram Mandir in Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh is believed to be built on top of the village where Krishna and Balarama grew up.

Pop Culture

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness, based around the Hindu practice of bhakti (“devotion”) to Krishna, is well known for its proselytizing efforts. A common devotional practice in this movement, and in Hinduism generally, is kirtan, a type of music that makes use of rhythmic chanting of “Hare-Krishna.”