Khoisan Religion

San women partaking in the trance healing dance photographed by Kgara Kevin Rack (2015).

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Overview

The Khoisan religion is an amalgamation of the beliefs of two distinct cultures: the Khoekhoe (also known as Khoikhoi) and the San (also known as Ju). Both are aboriginal tribal cultures from Southern Africa, though each tribe has its own deities and myths.

Historically, the Khoekhoe people were mostly farmers, while the San were nomadic hunter-gatherers. Both groups were seasonal migrators, inhabiting regions that correspond to modern-day Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa.

The Khoekhoe cultural group is made up of several different religious communities. Likewise, the San people are divided into a number of smaller groups or clans, often with fewer than one hundred members each.[1] Every Khoisan group “has its own dialect, such as Kung and Auni, and some even have a separate language such as [Cham] (|Xam).”[2]

Because of this linguistic and cultural diversity, it is somewhat misleading to speak of a unified Khoisan religion. Indeed, “Khoisan” is simply a catch-all term for the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who speak click languages rather than Bantu languages.

Oral Tradition

As with many African religions, the Khoisan religion is grounded in oral tradition, which has resulted in a number of variations on each myth. As stories are passed down through the generations, elements of those stories are altered, with information being added or lost along the way.

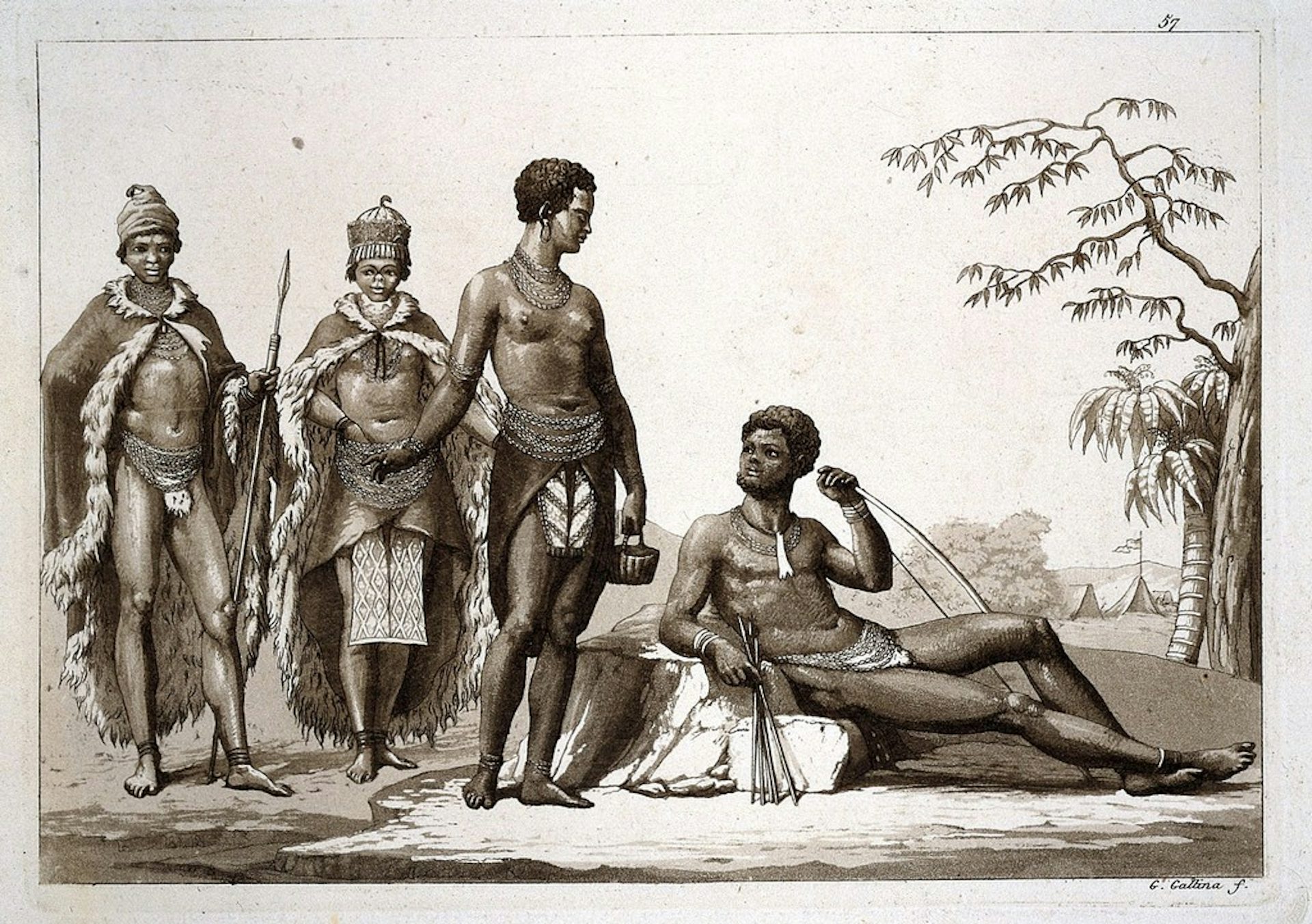

Khoi people of the Gonaqua kingdom, southern Africa, by G. Gallina, (c.1819).

Artstor Public CollectionCC BY 4.0Moreover, since these myths come from many different tribes, the characteristics of any given deity may differ according to the particular storyteller’s cultural identity.

This guide is an attempt to consolidate the most common myths and deities in the recorded literature, while acknowledging that the religion does not have a unified set of beliefs or practices.

Pantheon

The pantheon of the Khoisan religion is complex and difficult to pin down. Each tribe seems to worship a supreme being, but since the various Khoisan mythologies are derived from many different tribes, the identity of that supreme being varies. The chief deity is typically joined by a number of lesser gods and heroes.

The Supreme Deity

Each tribe has its own name, attributes, and myths for the Khoisan supreme deity. Even so, all agree that this supreme being is the creator god.

Kaggen is the chief deity of the San people. He is most often described as a praying mantis with trickster attributes. Kaggen appears in most San myths, as he is the god responsible for creating all living beings. Kho is another name for Kaggen, used by the San people when they are referring to the moon—one of the supreme being’s many forms.

Photograph of rock art on the Sevilla Rock Art trail in the Oliphants River Valley, Clanwilliam, Western Cape, South Africa. It is estimated to be between 800 to 8000 years old, by unknown San artist (n.d.).

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Tsui-Goab, meanwhile, is the chief deity of the Khoekhoe people. His name translates to “Wounded Knee,” referring to an injury he sustained in his battle with Gaunab, the god of darkness. Tsui-Goab is responsible for bringing the dawn to earth each day by vanquishing Gaunab every night.[3]

Hishe (also known as Gauwa) is another Khoekhoe creator god; his name means “The One Whom No One Can Command.”[4]

The Heroic Figure

Many of the key figures of Khoisan mythology were originally mortal but were later deified. These heroic characters are sometimes viewed as manifestations or aspects of the supreme being.

Gaona is a mythical hero of the !Kung tribe (one of the three main subgroups into which the San people are divided).[5] In some traditions, Gaona is not only a hero but also a creator deity, appearing under the names Hishe and Gauwa (see above).[6]

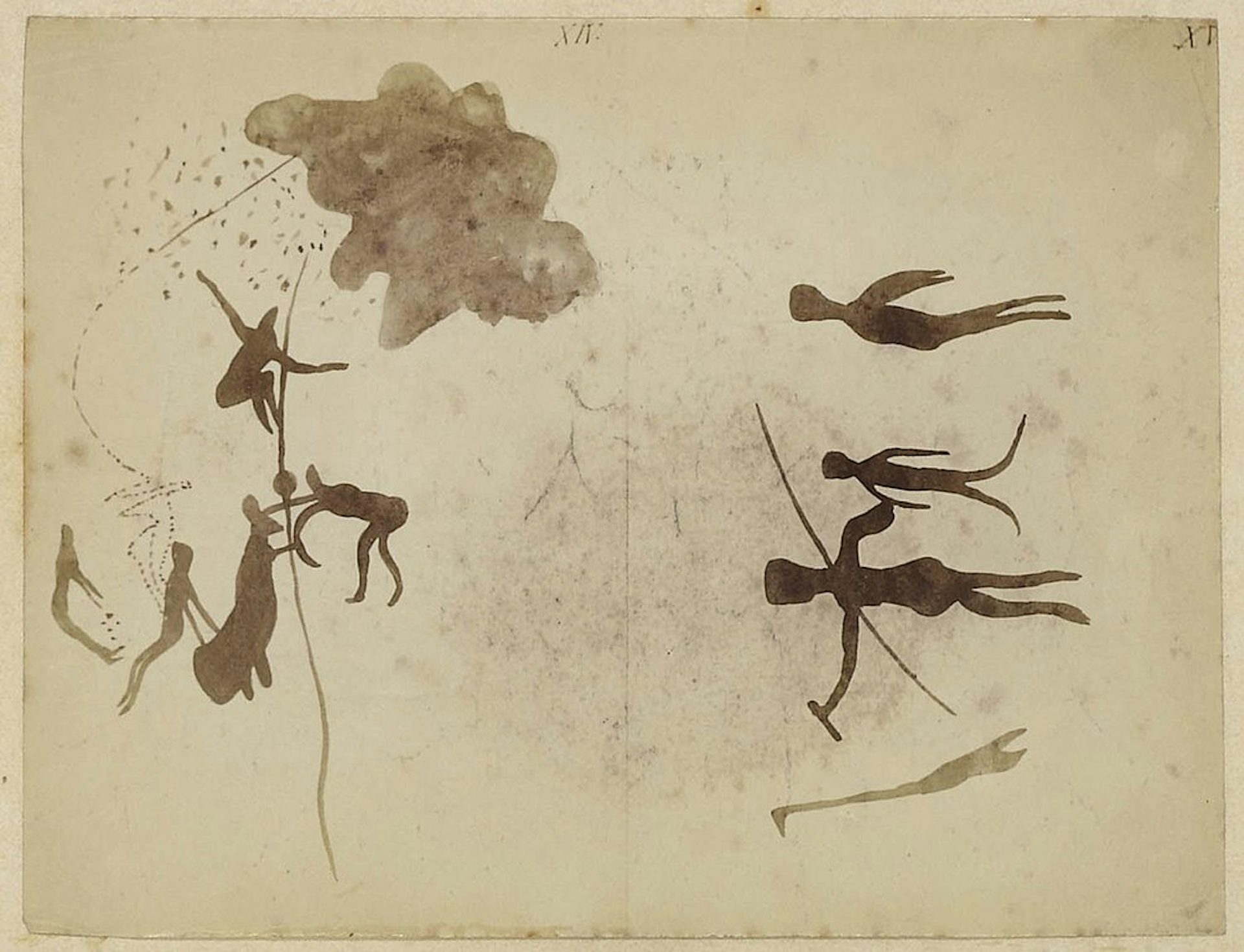

Drawing of San Rock Art from the National Museum of World Cultures, by unknown artist (pre-1882).

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY 4.0Kai Kini is another notable San hero; he was the first person to possess fire and eat cooked food. But the god Gaona stole Kai Kini’s fire sticks and scattered them throughout the world, claiming that it was unjust for one man to keep fire all to himself. In the end, Gaona turned Kai Kini into a bird.[7]

Heitsi-Eibib is a Khoekhoe mythical hero and god. After dying multiple times, he was ultimately deified and became the god of hunting. He is best known for defeating the man-eating monster Ga-Gorib.[8]

Other Gods

Other gods also play a key role in the Khoisan religion. Gaunab, for example, is the Khoekhoe god of death and darkness. He engages in battle each night against the god of light, Tsui-Goab. As the personification of evil and death, he is highly feared.[9]

Mythology

The idea of a “master animal” is central to San mythology. The eland (antelope) and the praying mantis are often associated with the San supreme being, who is believed to transform himself into these creatures. Scholars have discovered rock paintings and engravings up to 30,000 years old that represent these animals and their connection with the supreme being.[10]

Creation of the Milky Way and Orion’s Belt

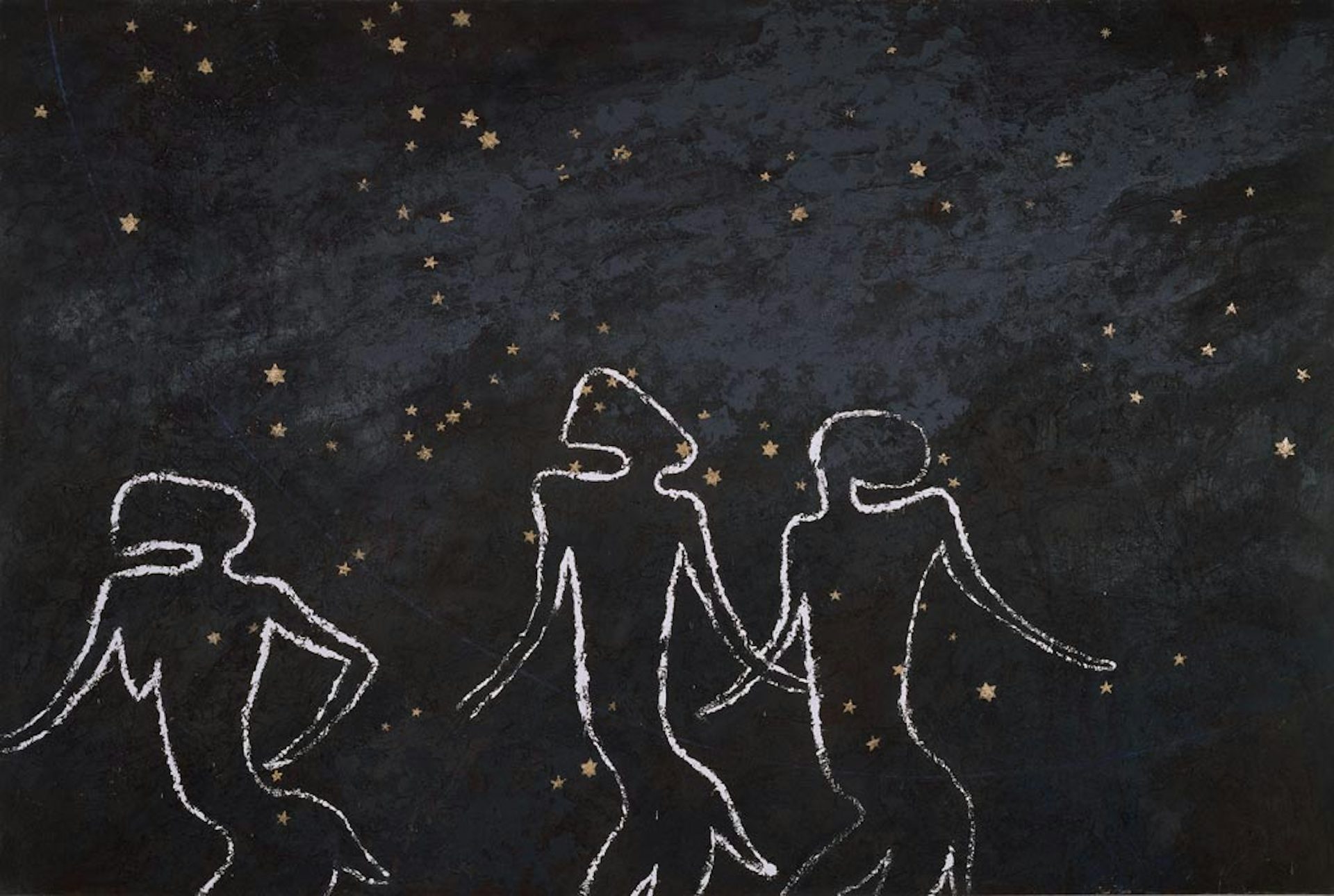

An acrylic painting depicting the San account of the creation of the Milky Way, by Gavin Jantjes (1989-1990).

National Museum of African ArtCopyrightAccording to Khoisan tradition, a young girl was once angry at her mother for not giving her any more delicious !huin roots to roast over the fire. In a fit of rage, she grabbed the ashes from the fire and scattered them across the sky.

From the ashes, red and white stars formed. These stars stayed wherever they had been thrown and became the Milky Way, which illuminates the night sky for hunters in search of prey.[11]

In another story of astrological creation, there was a young girl who possessed the ability to turn animals into stars simply by looking at them. She used her magic to transform a group of lions into stars, which became the constellation Orion’s Belt.[12]

The Creation of the Sun and Moon

According to Khoisan mythology, the sun was once a man. He had a powerful light that shone from his armpits; whenever he lifted his arms, daylight was created. But as he grew old and slept too long, the people grew cold.[13]

One day, some children snuck up on him and threw him into the sky, where he became round. There he stayed and was transformed into the sun, which always shines during the hot days in the desert.[14]

The god Kaggen, meanwhile, created the moon. Unable to see as he walked through the desert, the god threw his sandal into the sky. The sandal remained in the heavens and became the moon. An alternate version states that the moon was once an ostrich feather, which Kaggen threw into the air after wiping his tears with it.[15]

The Creation of Humankind

There are many variations on the Khoisan myth of humanity’s origins. One familiar San account claims that the first humans crawled through the roots of a tree and emerged from a hole in the ground.[16] They were closely followed by all the animals that now inhabit the earth.[17] The god Kaggen is said to have created both the hole and the people who came out of it.

An alternate San tradition agrees that Kaggen created humans but claims that these first humans angered the god, who destroyed them with fire and returned them to the sky.[18]

Beliefs and Worship

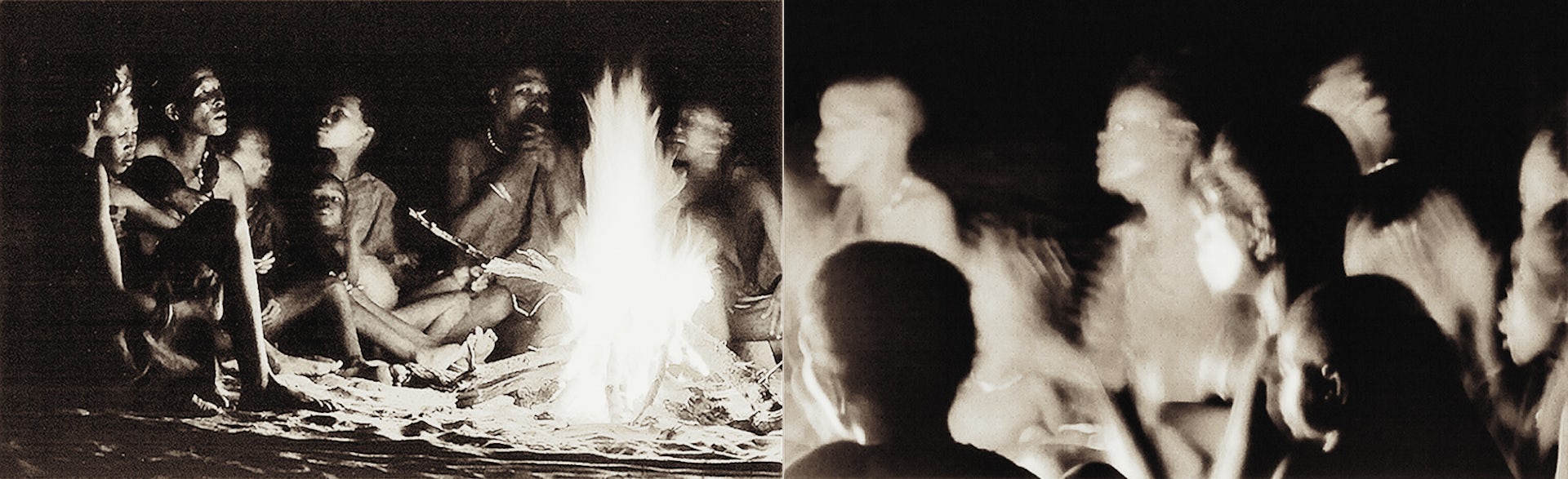

The Shaman Healing Dance photographed by Bradshaw Foundation, (n.d).

Bradshaw FoundationCopyrightTrances and Rituals

Adherents of the Khoisan religion often perform trance dances during healing ceremonies. In these ceremonies, the women of the tribe sit around a fire while the men dance around them.

San performing a dance at Camp Jao in Botswana photographed by Justin Hall, (2007).

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY 2.0Ritual specialists or shamans, who are mostly men, enter a trance-like state, which allows them to travel outside of their bodies. During these travels, they fend off the malevolent spirits responsible for causing illness.[19]