Hydra

Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra by Gustav Moreau (1875-1876).

The Art Institute of ChicagoCC0Overview

The Hydra, also called the Lernean Hydra (because it lived near Lerna in Greece), was part of a brood of ancient mythical monsters. Its parents were the creatures Typhoeus and Echidna, and its siblings included other multi-headed beasts, such as Cerberus and the Chimera. The Hydra itself was a serpent with numerous heads (the exact number varied in ancient sources). Its blood and even its breath were poisonous.

Hercules and the Hydra by Antonio del Pollaiolo (ca. 1475).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe Hydra was eventually killed by Heracles, who was sent to fight it as one of his Twelve Labors. After a long struggle, Heracles found a way to prevent the Hydra’s heads from regenerating when he cut them off. Once the monster was finally dead, Heracles dipped his arrows in its poisonous blood; he would go on to use these poisoned arrows in many future battles.

Etymology

The Greek word hydra means “water snake.” It is clearly related to other Indo-European words for water creatures, including udrá- (Sanskrit), udra- (Avestan), ū́dra (Lithuanian), výdra (Russian), ottar (Old High German), and the English word otter.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Hydra Ὕδρα Phonetic

IPA

[HAHY-druh] /ˈhaɪ drə/

Titles and Epithets

The Hydra was often called the “Lernean Hydra,” after the swamp it inhabited in Lerna.

Attributes

Locale

The Hydra lived in the swamps near Lerna, a town in the eastern Peloponnese. Ancient authors claimed that the creature haunted a spring named for Amymone, a daughter of Danaus and a lover of Poseidon, until it was finally killed by Heracles.

Appearance and Abilities

Though the Hydra was (as far as we know) always imagined as a many-headed creature, there was no consensus as to the exact number of heads or its other attributes and abilities.

The earliest known depiction of the Hydra was found on a pair of bronze fibulae (decorative brooches or pins) made in Boeotia around 700 BCE; it showed the monster with six heads. Literary representations of the Hydra began to appear around the same time, starting with Peisander in his lost epic the Heraclea (late seventh century BCE). However, Peisander failed to specify exactly how many heads the Hydra had.[2]

Later poets gave a range of suggestions for the number of heads. In the sixth century BCE, for example, the poet Alcaeus said that the Hydra had nine heads. This number was probably the most popular one in antiquity.[3] But other sources gave the Hydra as few as three heads[4] or as many as fifty[5] or one hundred.[6]

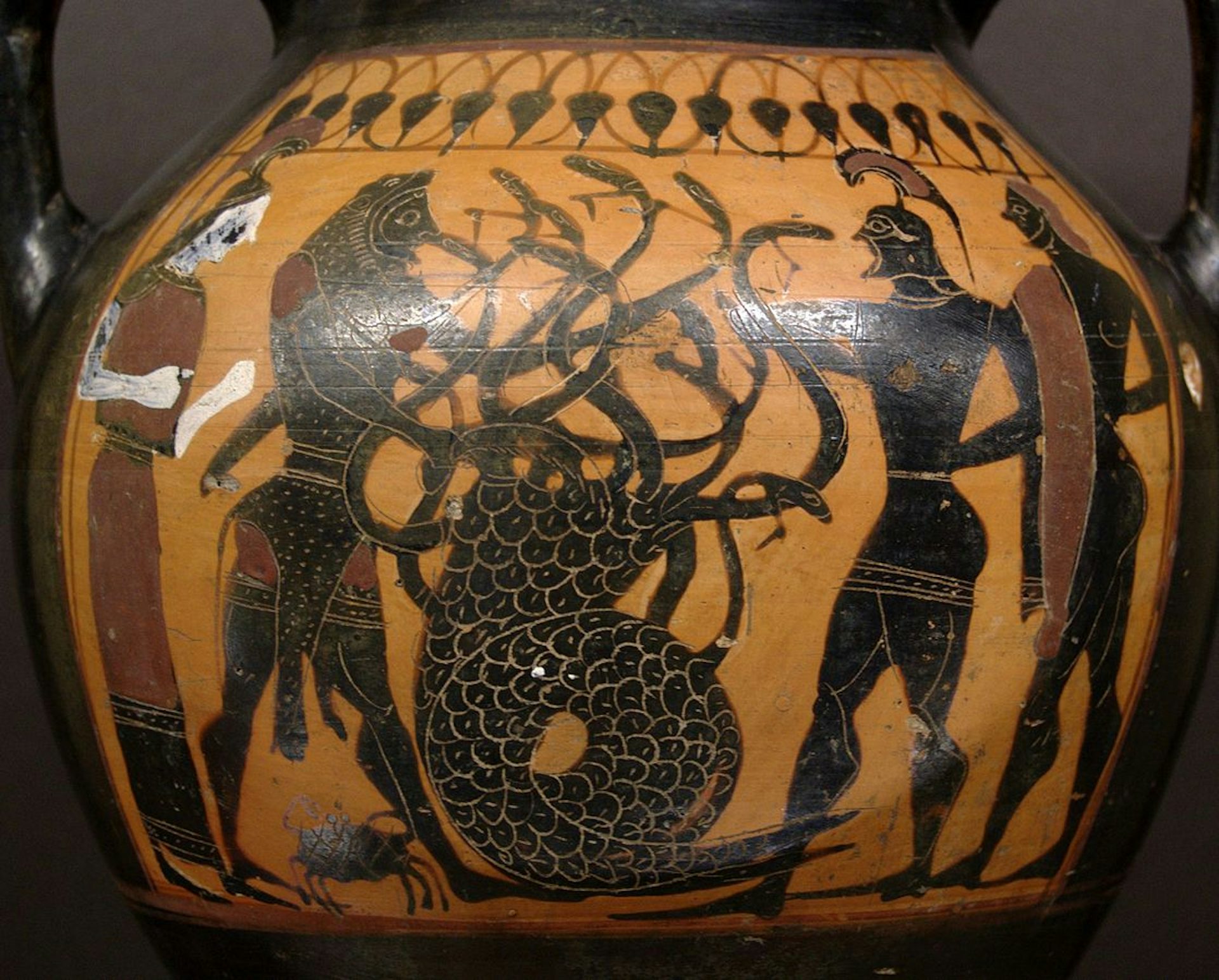

Vase painting showing Heracles and Iolaus fighting the Hydra, in the manner of the Princeton Painter (ca. 540–530 BCE). The Hydra is here depicted with eleven heads—a number not attested in any literary sources. Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAnother important attribute of the Hydra was its ability to regenerate its heads. This was likely not a part of the earliest versions of the myth, where the creature’s many heads were sufficiently terrifying on their own. But by the first century BCE, it was commonly said that the Hydra regrew two[7] or even three[8] heads for every one that was cut off. Taking this ability into account, the Hydra could have started out with any number of heads and then increased them exponentially.

Some sources claimed that one of the Hydra’s heads was immortal, while the other eight (or however many there were) were mortal (but could regenerate).[9]

The Hydra also exuded deadly poison. According to Hyginus, the creature was “so poisonous that she killed men with her breath, and if anyone passed by when she was sleeping, he breathed her tracks and died in the greatest torment.”[10] The Hydra’s poison was said to give the swamps and springs in which it lived a terrible smell.[11] Even the smallest contact with the Hydra’s blood could be fatal; Heracles used this to his advantage by dipping his arrows in the monster’s blood after he had killed it.

Iconography

The appearance of the Hydra was even more scattered and inconsistent in the visual arts. On ancient vase paintings, for example, it was not unheard of for the Hydra to be represented with seven, eight, ten, or eleven heads—numbers otherwise unattested in the literary traditions.

In some art from the Imperial period (32 BCE–476 CE), the Hydra was shown with Gorgon features, such as the head or even the torso of a human female. But these depictions were a later development of the myth, and relatively rare.[12]

Other Interpretations

Some ancient writers tried to come up with a rational explanation for the myth of the Hydra. Heraclitus, for example, suggested that the Hydra really had only one head, but was accompanied by its numerous brood—that is, the Hydra was really many snakes rather than a single many-headed snake.[13]

Family

Family Tree

Mythology

Heracles’ Second Labor

The battle between the Hydra and Heracles was no accident. According to the seventh-century BCE poet Hesiod, the terrible creature was raised by Hera for the express purpose of slaying Heracles, whom she hated as an illegitimate son of her husband Zeus.[15]

As part of Hera’s scheme, Heracles was ordered to fight the Hydra during the second of his famous Twelve Labors—punishments for having accidentally killed his family.

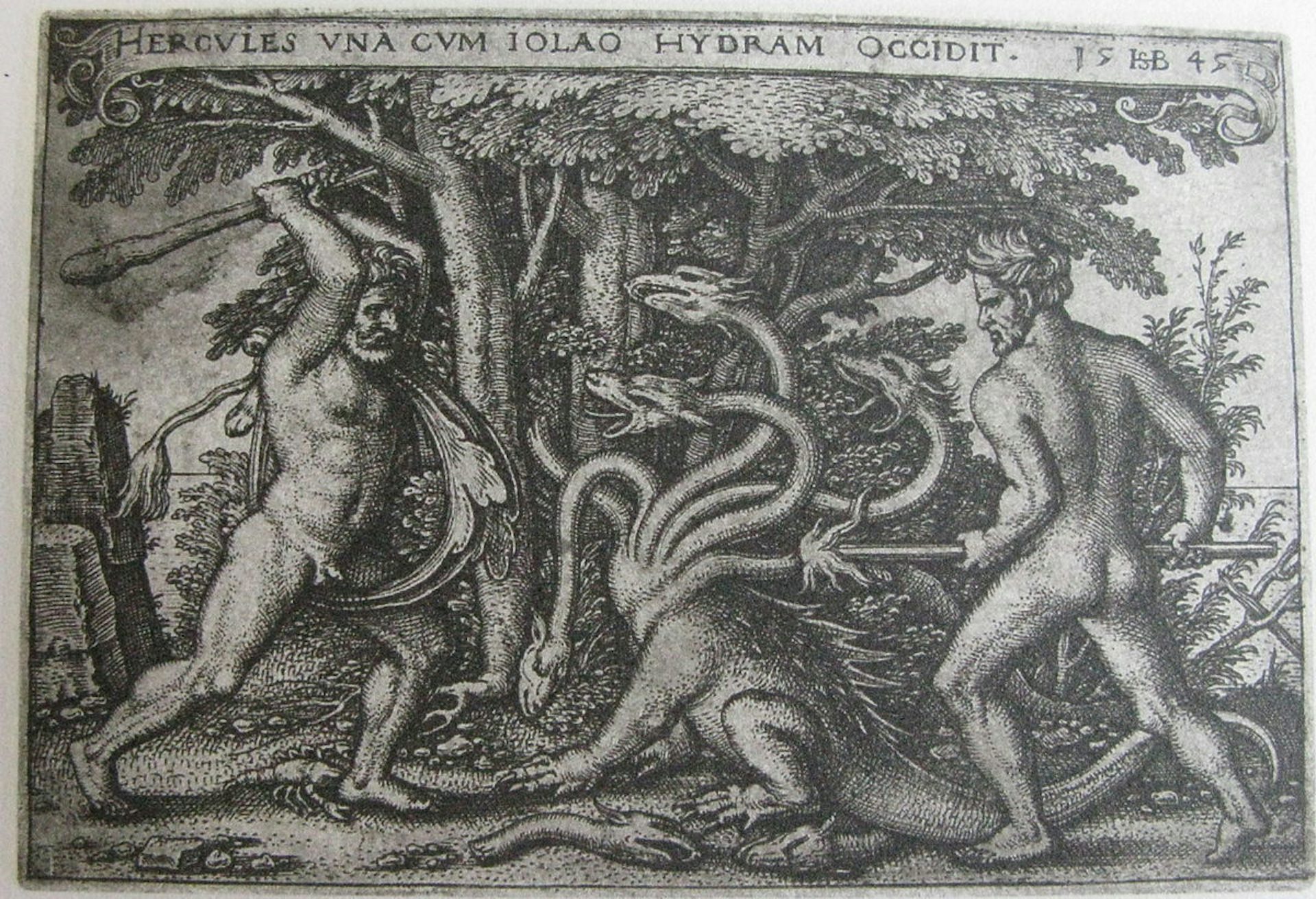

According to the most familiar version of the myth, Heracles found the Hydra in its swamp near Lerna and attacked it with the help of his nephew Iolaus. But each time Heracles cut off one of the monster’s heads, he discovered, to his horror, that several new heads grew back in its place. Eventually he realized that he could prevent the heads from growing back by quickly cauterizing the stumps with fire. Thus, every time Heracles cut off a head, Iolaus scorched it with a torch so that it would not grow back.[16]

Hercules and Iolaus killing the Hydra by Hans Sebald Beham (ca. 1545).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainApollodorus wrote that the Hydra’s middle head was immortal. Thus, after Heracles cut it off, he buried it in the ground and covered it, still thrashing, with a large boulder. The ancient Greeks believed that that boulder could still be seen on the road to Lerna.[17]

In some traditions, Hera sent a giant crab to help the Hydra in its fight with Heracles. The crab bit Heracles, but this only enraged the hero, and he easily crushed it to death. Both the Hydra and the crab were transformed into constellations after their deaths: the Hydra became the constellation Hydra, while the crab became Cancer.[18]

The Arrows of Heracles and the Hydra’s Revenge

After Heracles had killed the Hydra, he coated the tips of his arrows in its poisonous blood. These poisoned arrows accompanied Heracles in many of his subsequent battles.

One of the victims of Heracles’ poisoned arrows was the centaur Nessus. When Nessus tried to rape Heracles’ wife Deianira, Heracles shot him down. Knowing that the Hydra’s poison was running through his veins, Nessus laid one final snare: he told Deianira to keep a vial of his blood as a love potion. If Heracles’ love for Deianira ever wavered, said Nessus, she could sprinkle some of the blood on Heracles’ clothing and it would renew his affections. This was all a cunning lie, of course: Nessus knew that the Hydra’s poison within his blood would destroy anybody who touched it.

Years later, Deianira followed Nessus’ advice: she sprinkled his blood on one of Heracles’ tunics, and the Hydra’s poison burned him alive. This was the Hydra’s ultimate revenge: in the end, the monster was able to defeat Heracles after all.[19]

Pop Culture

The Hydra has had a long and colorful afterlife in modern pop culture. The mythical creature has been adapted by writers such as H. P. Lovecraft and Henry Kuttner. A 2009 monster movie, titled simply Hydra, was also inspired by the many-headed serpent of Greek mythology. Moreover, the name “Hydra” was given to a villainous organization in the Marvel Comics and Marvel Cinematic Universe; the organization’s name is evocative of its wide reach and numerous members, and its motto is an allusion to the mythical Hydra’s power of regeneration (“if a head is cut off, two more shall take its place”).