Heraclids

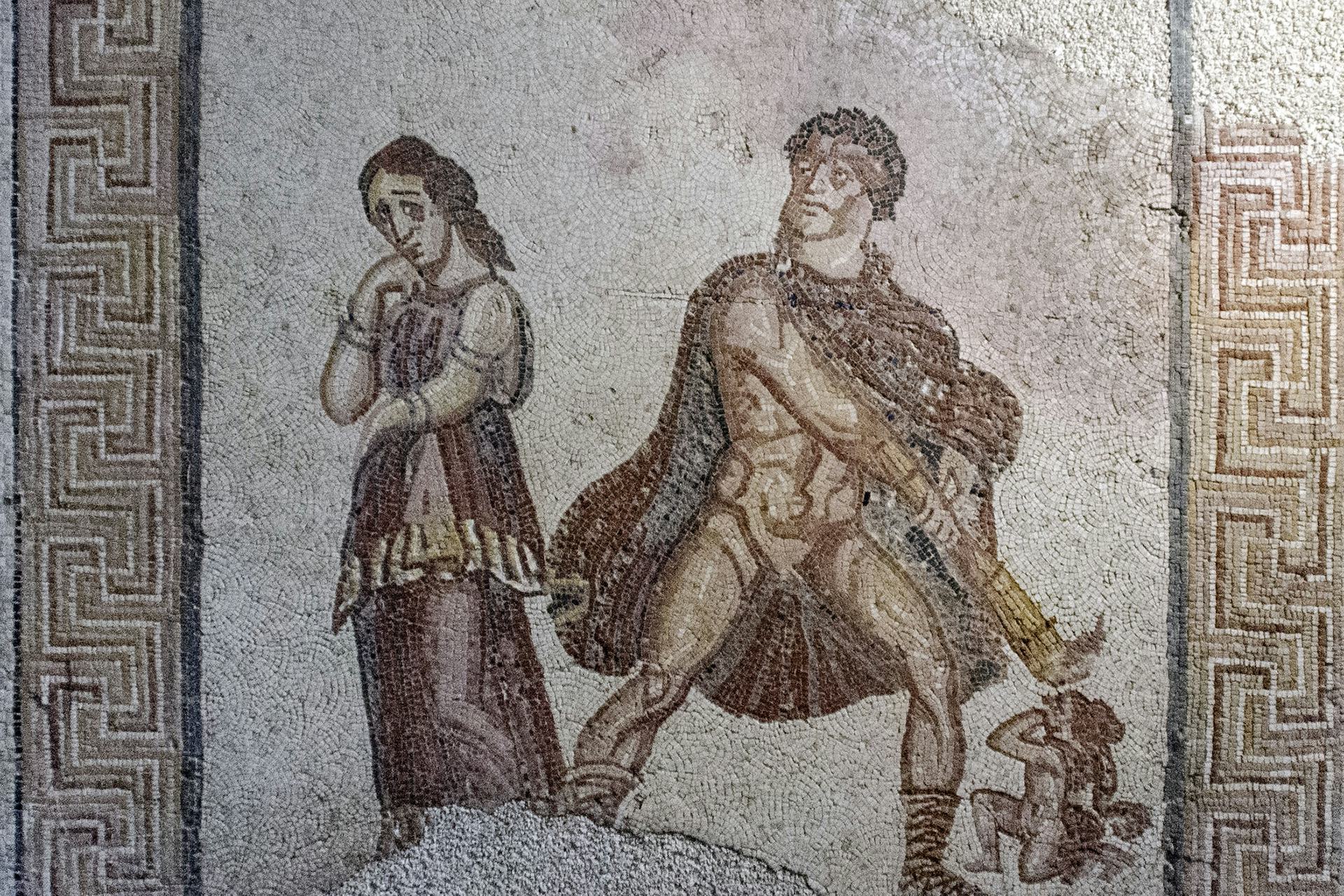

Mosaic panel showing the mad Heracles (center) killing his child (bottom right) as his wife Megara (left) stands by (third or fourth century CE). From the Villa Torre de Palma near Monforte.

National Archaeology Museum, Lisbon / Ángel M. FelicísimoCC BY 2.0Overview

The Heraclids or Heracleidae were descendants of the hero Heracles, comprising both his own children and the descendants of those children. The most famous Heraclids included Hyllus, whose descendants invaded Greece, as well as Telephus and Tlepolemus, who were involved in the Trojan War.

After Heracles’ death, the Heraclids were pursued and nearly wiped out by Heracles’ old enemy Eurystheus. Driven out of Greece, they eventually returned with an unstoppable army and proceeded to conquer Mycenae, Sparta, and Argos, among other cities. Some historians have argued that the myth of the Heraclids’ conquest of the Peloponnese was inspired by the “Dorian invasion,” a real historical event. Throughout Greek history, the rulers of cities such as Sparta continued to claim Heracles as their ancestor.

Etymology

The term “Heraclids” (Greek Ἡρακλεῖδαι, translit. Hērakleîdai) is a patronymic, meaning “sons” or “children” of Heracles.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Heraclids Ἡρακλεῖδαι (Hērakleîdai) Phonetic

IPA

[HER-uh-klidz] /ˈhɛr ə klɪdz/

Mythology

The First Generation

Since nearly all of Heracles’ countless marriages, affairs, and dalliances produced offspring, ancient mythical sources name more than one hundred children of Heracles.

The Children of Heracles

According to the most familiar accounts, Heracles’ prolific procreation began with the daughters of Thespius. According to this myth, King Thespius of the Boeotian city of Thespiae allowed Heracles to sleep with all fifty of his daughters as a reward for hunting down the fearsome Cithaeronian Lion that was ravaging his lands. Each of these fifty women gave Heracles at least one son.[1]

Heracles was later married at least twice: first to Megara, the daughter of the Theban king Creon, and then to Deianira, the daughter of the Calydonian king Oeneus. Both of these marriages gave Heracles additional children. Though Heracles was driven mad by the goddess Hera and ended up killing his children by Megara (as well as Megara herself, in some accounts),[2] the children he had with Deianira survived—including, most famously, his firstborn son Hyllus.[3]

Deianira by Evelyn De Morgan

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainHeracles also had children with many other women (as well as with some goddesses and even monstrous beings). These included children by the Lydian queen Omphale[4] and by his divine wife Hebe, whom he married after dying and becoming a god.[5]

Some of Heracles’ children were famous in their own right. Tlepolemus, for example, became king of the island of Rhodes and fought with the Greeks during the Trojan War.[6] According to Homer’s Iliad, he was killed in battle by Sarpedon, a son of Zeus and one of Troy’s most formidable allies.[7]

Telephus, Heracles’ son by the Tegean princess Auge, became ruler of the Mysians in western Anatolia. In one myth, the Greeks accidentally attacked Telephus’ kingdom on their way to fight the Trojan War. Telephus himself was wounded by Achilles, but was later cured in return for his help in guiding the Greeks to Troy.[8]

Eurystheus

The Heraclids are perhaps best known for the persecution they suffered after Heracles’ death. Eurystheus, the king of Mycenae who had assigned Heracles his famous Twelve Labors, was especially determined to hunt down and kill all of Heracles’ descendants.

The enmity between Heracles and Eurystheus actually began before either of them was born. Heracles’ father Zeus had originally intended for Heracles to become the king of Mycenae, but his plan was undermined by the trickery of Hera (who was jealous of her husband’s illegitimate child). Thus, Eurystheus, one of Heracles’ cousins, became king instead. Later, Hera helped Eurystheus devise impossible labors for Heracles, hoping he would perish while trying to complete them.

With Heracles now dead, Eurystheus feared that the hero’s children would someday seek to avenge their father. This is why he hoped to exterminate Heracles’ bloodline completely.

Attic black-figure neck amphora showing Heracles holding the Erymanthian Boar over Eurystheus as he cowers in a storage jar (ca. 520 BCE)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0After running from their enemies for years, the Heraclids were finally given refuge by the city of Athens. When the Athenians refused to surrender the Heraclids, Eurystheus attacked, but he was ultimately defeated and killed.[9]

Exile of the Heraclids

After the defeat of Eurystheus, Hyllus (Heracles’ son by his second wife Deianira) led the Heraclids in an invasion of the Peloponnese. Because their father had been destined to rule the Peloponnese from Mycenae, the Heraclids regarded this territory as their birthright; indeed, their invasion was often called a “return.”

A photo of the Lions Gate in Mycenae

Andreas TrepteCC BY-SA 2.5The Heraclids were initially successful, conquering many cities, but their ranks were soon devastated by a plague. Hyllus learned from an oracle that the plague had appeared because they had not come back at the proper time. According to the Oracle of Delphi, the Heraclids needed to wait for the “third crop” before returning to the Peloponnese.

Hyllus believed that the “third crop” meant three years, so after waiting the allotted amount of time, he again invaded the Peloponnese. But the Heraclids were defeated at the Isthmus of Corinth, a narrow strip of land connecting the Peloponnese to the rest of mainland Greece. Hyllus himself was killed in battle, and the Heraclids went back into exile in the north for a period of fifty years or more.[10]

Later Generations: The Return of the Heraclids

The Conquest of the Pelopponese

Hyllus’ invasion was followed by two more failed offensives. The first was led by Hyllus’ son Cleodaeus, and the second by Cleodaeus’ son Aristomachus. Both Cleodaeus and Aristomachus were killed in battle, and their forces were routed.

Finally, Aristomachus’ three sons—Temenus, Cresphontes, and Aristodemus—consulted Delphi again. This time, they learned that the “third crop” referred not to three years but to three generations. They were also given clearer instructions on where to attack: not the Isthmus of Corinth but the straits of Rhium, to the west of the Peloponnese.

While the Heraclids were preparing their invasion, Aristodemus (one of the sons of Aristomachus) was killed. His command passed to his two sons, Eurysthenes and Procles.

The Heraclids were warned that their invasion would succeed only if they found a three-eyed guide. By chance, they came upon Oxylus, a man from the Peloponnesian kingdom of Elis, who was riding a one-eyed horse. With him as their guide, the Heraclids invaded the Peloponnese once more.

In the ensuing battles, the Heraclids were successful at last. They beat the king of Mycenae, a man named Tisamenus (the grandson of Agamemnon, who had led the Greeks during the Trojan War). But Pamphylus and Dymas—leaders of the northern Greek tribes known as the Dorians and allies of the Heraclids—were killed in the invasion. Thus, in the end it was the great-great-grandsons of Heracles who conquered the Peloponnese.

After the war was over, Temenus, Cresphontes, and the two sons of Aristodemus (Eurysthenes and Procles) drew lots to decide how to divide the Pelopponese. Temenus won Argos and the Argolid; Cresphontes won the fertile region of Messenia; and Eurysthenes and Procles won Laconia, whose capital was Sparta. Throughout Greek history, the rulers of these three regions continued to trace their genealogy to Heracles.[11]

Illustration of Lacedaemon (Sparta).

Nuremberg ChroniclePublic DomainMyth versus History: The Dorian Invasion

In the nineteenth century, historians began to argue that the myth of the “return of the Heraclids” was based on a real historical migration of northern Greek tribes into central Greece. This migration was thought to explain why certain pre-classical dialects of the ancient Greek language were replaced throughout much of central Greece. The new dialect was called the Dorian dialect, and the migration was dubbed the Dorian invasion. With a bit of imagination, the Dorians who migrated and conquered the Peloponnese came to be identified with the Heraclids and their mythical conquest.

After extensive research, however, scholars have concluded that there is no concrete archaeological or historical evidence that a large-scale Dorian invasion ever took place. The myth of the Heraclids may well have been based on several smaller-scale migrations, but what really inspired the stories of their conquest is likely to remain a mystery.[12]

Worship

A handful of Heracles’ children and descendants were objects of hero cult worship. Tlepolemus, for example, was worshipped in Rhodes as the founder of an important settlement and kingdom,[13] while Telephus likely received heroic honors in Anatolia. Antiochus, a relatively minor son of Heracles, was revered in Athens as one of the original ten “eponymous heroes” from whom the names of the city’s tribes were derived. Overall, however, the cults of the individual descendants of Heracles were far eclipsed by that of their mighty progenitor.