Heracles (Play)

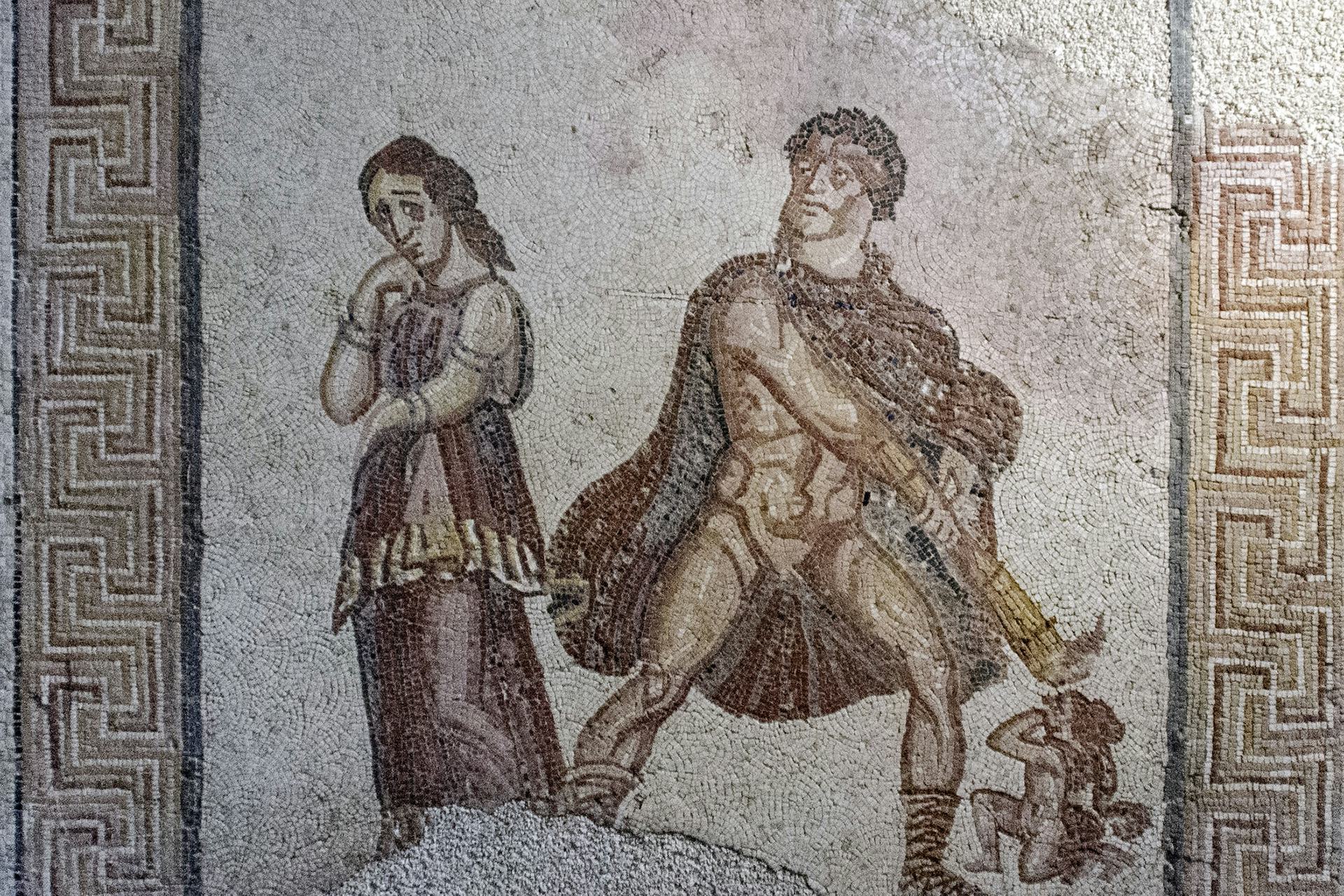

Mosaic panel showing the mad Heracles (center) killing his child (bottom right) as his wife Megara (left) stands by (third or fourth century CE). From the Villa Torre de Palma near Monforte.

National Archaeology Museum, Lisbon / Ángel M. FelicísimoCC BY 2.0Overview

The Heracles is a Greek tragedy composed by Euripides. It was probably first performed around 415 BCE at the Great Dionysia, an annual dramatic festival in which playwrights would compete to entertain the citizens of Athens. It is unknown, however, how the play fared in this competition.

Set in front of Heracles’ palace in Thebes, Euripides’ Heracles dramatizes the hero’s madness and subsequent murder of his family. Notably, the play presents this familiar myth in a very unfamiliar way, placing the event after (rather than before) Heracles’ completion of his Twelve Labors.

Seen as an exploration of suffering, heroism, and the role of the gods in human life, the play continues to inspire adaptations in both literature and the visual arts.

Title

The play was probably originally titled simply Heracles (Greek Ἡρακλῆς, translit. Hēraklês). Many subsequent sources, however, have referred to it as Ἡρακλῆς μαινόμενος (translit. Hēraklês mainómenos), “The Mad Heracles,” or as Hercules Furens, the Latin translation of that title. This was likely done to distinguish it from other plays by Euripides that also treated the myth of Heracles.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Heracles Ἡρακλῆς (Hēraklês) Phonetic

IPA

[HER-uh-kleez] /ˈhɛr əˌkliz/

Author

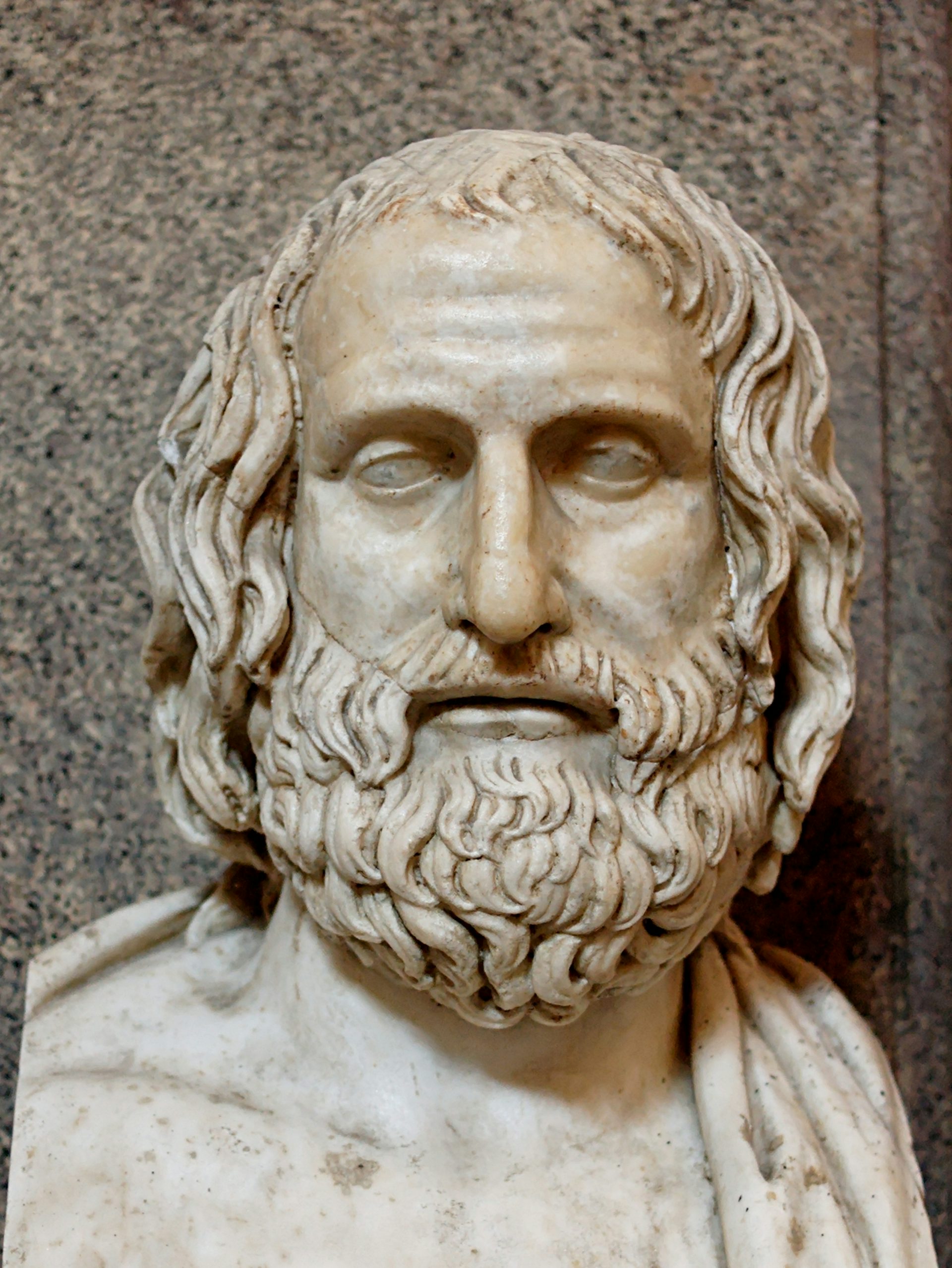

Euripides, the author of the Heracles, was an Athenian tragedian who is thought to have lived from approximately 480 BCE to 406 BCE. He was the youngest of the three canonical Athenian tragedians (the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles) and was known for exploring avant-garde, subversive, and innovative themes.

Roman bust of Euripides after a Greek original from ca. 330 BCE

Vatican Museums, Vatican / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainOver the course of his career, Euripides composed some ninety plays, eighteen of which survive in full.[1] Despite his formidable output—we have more plays by Euripides than by Aeschylus and Sophocles combined—he won only four victories at the Dionysia during his lifetime (with a fifth awarded the year after his death). Yet Euripides’ popularity and literary influence have continued to grow, and some now regard him as the greatest of the Athenian tragedians.

Little is known about Euripides’ personal life; most ancient testimonia and biographies read more like fable than fact. Euripides seems to have been born on Salamis, an island near Athens, to a family of hereditary priests. He was married twice, both times unhappily, and had three sons. Ancient sources claimed that Euripides was a recluse and may have even lived alone in a cave in Salamis, though the veracity of such stories is obviously dubious. He died in 406 BCE at the court of the Macedonian king Archelaus.

Throughout his lifetime—and after his death, too—Euripides had a reputation as a challenging and controversial playwright. The comedian Aristophanes, one of his contemporaries, often mocked Euripides as an intellectual snob. The Heracles itself supposedly stirred up considerable controversy: according to one (probably unreliable) tradition, the Athenian politician Cleon had Euripides prosecuted for his impious staging of Heracles’ madness.

In time, however, Euripides came to be recognized for his capable exploration of emotional realism, his innovative treatment of traditional mythology, and his persistent questioning of contemporary values.

Mythological Context

Euripides’ Heracles adapts the story of Heracles’ madness in an unusual way. In most accounts of the myth, Heracles murders his family before completing the Twelve Labors. In fact, Apollodorus’ Library implies that Heracles was forced to complete the labors as atonement for killing his family.[2] In Euripides’ play, however, this sequence is reversed, with Heracles’ homicidal madness occurring after he has completed the labors. There are other ways in which Euripides’ Heracles departs from more traditional versions of the myth. For instance, the character of Lycus and his violent takeover of Thebes are largely Euripides’ inventions. As for the murders themselves, there are several conflicting accounts.

According to Apollodorus, Heracles killed not only his own children but also the children of his brother Iphicles—and he did so not with weapons but by throwing them into a fire.[3] According to other authors, Heracles only killed his children, while his wife Megara escaped. One brief poem, thought to have been written by Theocritus, even features Megara describing the murder of the children to Heracles’ mother Alcmene (while Heracles is away performing his labors).[4]

Euripides also deviates from tradition in his description of the Twelve Labors, with the play’s Chorus giving a very idiosyncratic list of Heracles’ labors in the first stasimon:[5]

The Mares of Diomedes

[Cycnus]

The Apples of the Hesperides

[Pacifying the sea]

[Holding up the heavens]

Several of these labors (indicated by square brackets in the list above) are not mentioned by any other sources, or are not traditionally counted among the Twelve Labors. Heracles’ battle with the Centaurs and his killing of Cycnus, for instance, were typically thought to have occurred either between his labors or after them, forming part of the parerga, or “minor labors.”

Other labors are presented in an unusual way. The Ceryneian Hind, for instance, was typically described as a speedy horned doe that Heracles needed to run down and capture alive.[7] But in Euripides’ play, the creature is described as a violent menace “that preyed upon the country-folk.”[8] Euripides also treats the apples of the Hesperides and the holding up of the heavens as two separate labors, while in other sources they were two parts of a single labor (with Heracles taking the heavens from Atlas so that Atlas could bring him the apples).

Finally, several canonical labors are never mentioned at all, including the Erymanthean Boar, the Augean Stables, the Stymphalian Birds, and the Cretan Bull. This is highly strange, as the Twelve Labors had been fixed since around 470 BCE, when they were depicted in sculpted relief on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. Perhaps Euripides was following a different, even earlier list that is now lost, or perhaps he wished to reduce the number of labors that took place in the Peloponnese in order to emphasize Heracles’ role as a Panhellenic hero—a benefactor of all Greece.

Hercules and the Hydra by Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1475)

Uffizi Gallery, Florence / Google Arts and CulturePublic DomainThe myth of Heracles’ madness predates Euripides and continued to be represented in literature and art after the Heracles. But despite its many idiosyncrasies, Euripides’ version of Heracles’ madness is perhaps the most recognizable literary depiction of this important episode from one of the most important Greek heroes.

Characters

The following is a list of characters from Euripides’ Heracles, in order of appearance:

Amphitryon (Heracles’ foster father)

Megara (Heracles’ wife; daughter of the Theban king Creon)

Chorus (elders of Thebes)

Lycus (usurping ruler of Thebes)

Heracles (hero of Thebes; son of Zeus and Alcmene; foster son of Amphitryon)

Iris (messenger of the gods)

Lyssa (“Madness” personified)

Messenger

Theseus (hero and king of Athens)

Synopsis

Euripides’ Heracles is set in front of Heracles’ palace in Thebes, where Heracles’ foster father Amphitryon, his wife Megara, and his three children sit as suppliants at an altar dedicated to Zeus the Savior.

In the prologue, Amphitryon delivers a monologue in which he describes the play’s backstory: he tells of Heracles’ parentage as the son of Zeus and the mortal Alcmene (Amphitryon’s wife); of the circumstances that drove the family to leave their homeland in Argos and settle in Thebes; of the Twelve Labors that Heracles agreed to perform for Eurystheus in exchange for his family’s return to Argos; of Heracles’ marriage to Megara, daughter of the Theban king Creon; and of the vicious conquest of Thebes by a usurper named Lycus, who assumed power in Heracles’ absence. Lycus now intends to kill Heracles’ entire family.

As Amphitryon ends his monologue, Megara interjects. In the dialogue that follows, Amphitryon and Megara discuss their situation. Amphitryon is hopeful that Heracles will return and rescue his family, while Megara has already resigned herself to their deaths.

The Chorus, made up of elders of Thebes, enters and sings their first choral song, the parodos. They express sympathy for the dire situation confronting Heracles’ family and lament the fact that they are too old and frail to help.

Lycus enters, and he and Amphitryon debate Heracles’ heroic virtue, or arete. Lycus is determined to exterminate Heracles’ family and orders his attendants to pile wood around the altar so that the suppliants can be burned alive. Megara declares that she plans to die with dignity, and she and her children are allowed to enter the palace so they can prepare themselves for death. Amphitryon, meanwhile, criticizes Zeus for abandoning Heracles and his children.

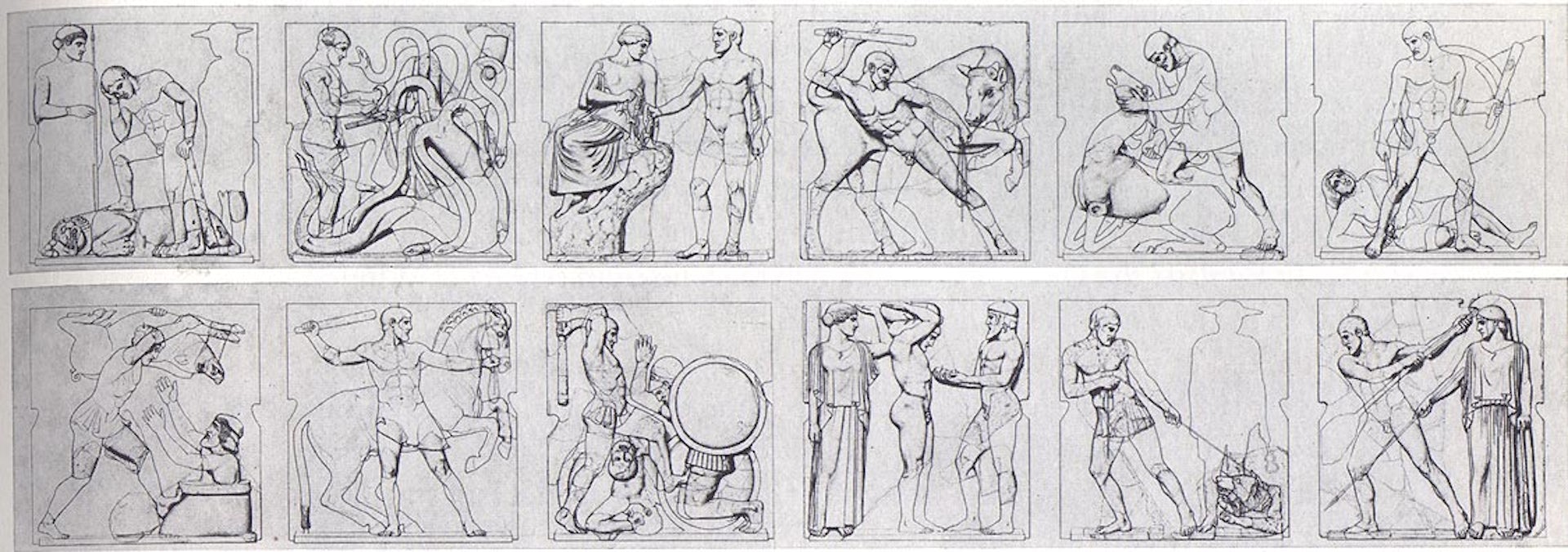

Nineteenth-century line drawing of the metopes on the east and west porches of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, showing the Twelve Labors of Heracles (ca. 470 BCE).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe Chorus sings the first stasimon, praising Heracles’ famous labors. They assume that Heracles is now dead.

The second episode begins with Megara and Amphitryon returning and resigning themselves to their fate. Suddenly, Heracles arrives, having just completed his final labor. When he discovers what has happened, he promises to kill Lycus and save his family. As Heracles and his family enter the palace to lay a trap for Lycus, the Chorus sings the second stasimon in praise of youth and Heracles’ strength.

The third episode sees Lycus enter and ask Amphitryon what is keeping Megara and the children. He goes into the palace to find them, where he is attacked and killed by Heracles. Upon hearing Lycus’ cries, the Chorus rejoices and sings the celebratory third stasimon.

Iris, the messenger of the gods, and Lyssa, the personification of madness, enter abruptly. On behalf of her mistress Hera, the queen of the gods, Iris commands Lyssa to drive Heracles mad so that he will kill his own family. Lyssa, though reluctant, carries out the order. The Chorus laments what is about to happen.

A messenger soon arrives and describes the madness that suddenly fell upon Heracles, causing him to kill his wife and children: apparently he hallucinated that they were his enemies. Thankfully, Athena appeared and knocked Heracles out before he could kill Amphitryon. Having been restrained, Heracles now lies unconscious inside the palace.

The Chorus sings the fourth stasimon, in which they compare Heracles’ actions to the myths of the Danaids and Procne. They conclude that what Heracles did was even worse.

In the exodus, Heracles regains consciousness and slowly (with the guidance of Amphitryon) comes to the terrible realization of what he has done. As Heracles contemplates suicide, his friend Theseus arrives. In a long dialogue, Theseus manages to convince Heracles to live on and endure his grief. The play ends with Heracles accompanying Theseus to Athens to seek purification.

Theseus Fighting the Centaur Bianor by Antoine-Louis Barye (modeled 1849, cast ca. 1867)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainStyle and Composition

We have no information on when Euripides’ Heracles was written or first staged. However, we can assume that, like Euripides’ other plays, the Heracles was performed as part of a tragic tetralogy (consisting of three tragedies and one satyr play) at the dramatic competition held during the annual Dionysia festival. Stylistic and metrical analysis of the play suggests that it was composed a little earlier than Euripides’ Trojan Women, which would place its date of performance around 415 BCE.

Themes

Suffering—and the question of how human beings ought to cope with suffering—is a central theme throughout Euripides’ Heracles. In the first part of the play, Amphitryon and Megara find themselves in a terrible situation, unable to rescue themselves or their children from the usurper Lycus. In the second part of the play, Heracles must find the strength to persevere even after his madness has driven him to kill his own wife and children.

This suffering, moreover, is often undeserved. Indeed, Hera drives Heracles to kill his family not as punishment for anything he has done but simply because he is the illegitimate son of her husband Zeus.

The Heracles also explores the meaning of heroism or heroic virtue—what the ancient Greeks called arete. Traditionally, arete was conceived as a masculine quality, defined by strength and bravery in battle. But Euripides expands arete to also include friendship (philia in Greek): in short, a man who is truly heroic is not merely brave but is also a good friend.

Euripides’ portrayal of Heracles exemplifies this new arete. This Heracles—in contrast to other versions of the hero—does not rely exclusively on his physical strength or abilities, instead using his wits and cunning when necessary. For instance, he sneaks into Thebes in disguise and ambushes Lycus, rather than facing him and his followers head-on. Nor is Heracles afraid to use long-range weapons such as the bow when confronted with a stronger foe. Similarly, Heracles emphasizes the importance of cooperation, valuing social relationships with family and friends over the glory of his labors.

Hercules the Archer by Antoine Bourdelle (1909)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art / PierreSelimCC0Heracles takes this new heroism even further when he ultimately rejects his own divinity, distancing himself from the injustice of the gods in favor of a kind of humanism. Euripides’ Heracles thus becomes an emphatically human hero.

Another important theme is the nature of the gods. By the end of the play, Heracles’ rejection of his divinity serves as an eloquent judgment on the (bad) behavior of the gods. But their nature is explored from the very beginning, with Amphitryon especially attacking the gods for their apparent abandonment of Heracles and his family.

Amazingly, Heracles refuses to believe that the gods are amoral or cruel (all evidence to the contrary), engaging Theseus in a theological debate that echoes ideas espoused by the philosophers of Euripides’ own time: if the gods exist, says Heracles, they do not harm one another or interfere in human affairs but are instead perfect, free of desires.

Within the reality of the play, of course, these speculations are groundless, and Heracles himself acknowledges that it is Hera’s unjust hatred for him that has caused his present suffering. All the same, Heracles’ reinterpretation of the gods serves to confirm his commitment to a new humanist heroism.

Reception

Though Euripides’ Heracles is one of the best-known retellings of the myth of Heracles’ madness, the play itself is not one of Euripides’ most influential. In the Augustan period, it was adapted by the Roman Seneca for his Madness of Hercules, and Seneca’s version ultimately became better known. Indeed, it was Seneca’s more blatantly aggressive and megalomaniacal Hercules—rather than Euripides’ ambiguous hero—who became the predominant influence on Renaissance adaptations of the tale.

Following the Renaissance, the Heracles—along with Euripides’ oeuvre as a whole—fell out of favor. The text enjoyed a bit of a resurgence in the nineteenth century, inspiring, for instance, a literary translation by Robert Browning in 1875. During this same period, the German scholar Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff produced his highly influential edition of the text.

More modern adaptations of Euripides’ mad Heracles have tended towards increasingly philosophical or psychological interpretations. The critic Hermann Bahr, for instance, has viewed the Euripidean hero as a powerful illustration of the potential of all human beings to lose themselves and their identity. Other writers, including George Cabot Lodge and W. B. Yeats, have interpreted Euripides’ Heracles as an example of Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Superman”—a being who attains divinity through madness and violence.

Contemporary adaptations of the Heracles generally emphasize the hero’s loss of self, often in the context of global wars (the Cold War, the Vietnam War, conflicts in the Middle East). These versions dramatize heroic trauma and the moral crises of civilizations that have lost their way. Daniel Algie’s 2006 play Home Front, for example, transforms Heracles into a traumatized Vietnam War veteran and reverses Euripides’ message about redemption by having the Theseus character kill Heracles (instead of encouraging him to live on, as he does in Euripides’ play).

Translations

Translations of the Heracles are usually found in volumes of Euripides’ collected plays. The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Coleridge, E. P., trans. The Plays of Euripides. Vol. 1. 9th ed. New York: Random House, 1938: Prose translation in Coleridge’s edition of the collected works of Euripides; can be viewed online through the Perseus Project.

Barlow, S. A., ed. and trans. Euripides: Heracles. Aris and Phillips Classical Texts. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996: Prose translation with facing Greek text; keyed to a commentary directed at beginners.

Kovacs, David, ed. and trans. Euripides, Vol. 3: Suppliant Women, Electra, Heracles. Loeb Classical Library 9. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998: An accurate prose translation; portions of the text that are regarded as later additions are enclosed in square brackets.

Davie, John, trans. The Heracles and Other Plays. Edited by Richard B. Rutherford. London: Penguin, 2003: An accurate and idiomatic prose translation, best suited to more knowledgeable readers.

Carson, Anne, trans. Grief Lessons: Four Plays by Euripides. New York: NYRB Classics, 2008: Contains verse translations of the Heracles as well as the Alcestis, Hecuba, and Hippolytus.

Waterfield, Robin, trans. Euripides: Heracles and Other Plays. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008: Accurate, clear, idiomatic prose translation with thematic introductions.

Arrowsmith, William, trans. Euripides, Vol. 3: Heracles, The Trojan Women, Iphigenia among the Taurians, Ion. 3rd ed. Edited by Mark Griffith and Glenn W. Most. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013: Readable and accurate verse translation with a basic introduction and notes.