Hecuba (Play)

The Despair of Hecuba by Pierre Peyron (ca. 1784)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

The Hecuba is an Attic tragedy composed by Euripides, one of the three canonical tragedians of classical Athens. We have no information on the context in which the play was first performed, though stylistic analysis suggests it was probably produced in the second half of the 420s BCE.

The Hecuba dramatizes the misfortunes of Hecuba, the wife of Priam and the former queen of Troy, after her city is sacked by the Greeks. Over the course of the play, Hecuba must live through the loss of two of her children: her daughter Polyxena and her son Polydorus. In the end, she enacts a brutal revenge on Polymestor, her son’s murderer. These events are used to explore the themes of suffering, endurance, vengeance, and nobility.

Title

Euripides’ Hecuba (Greek Ἑκάβη, translit. Hekábē) is named for Hecuba, wife of Priam and former queen of Troy, who was enslaved by the Greeks after their victory in the Trojan War.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Hecuba Ἑκάβη (Hekábē) Phonetic

IPA

[HEK-yoo-buh] /ˈhɛk yʊ bə/

Author

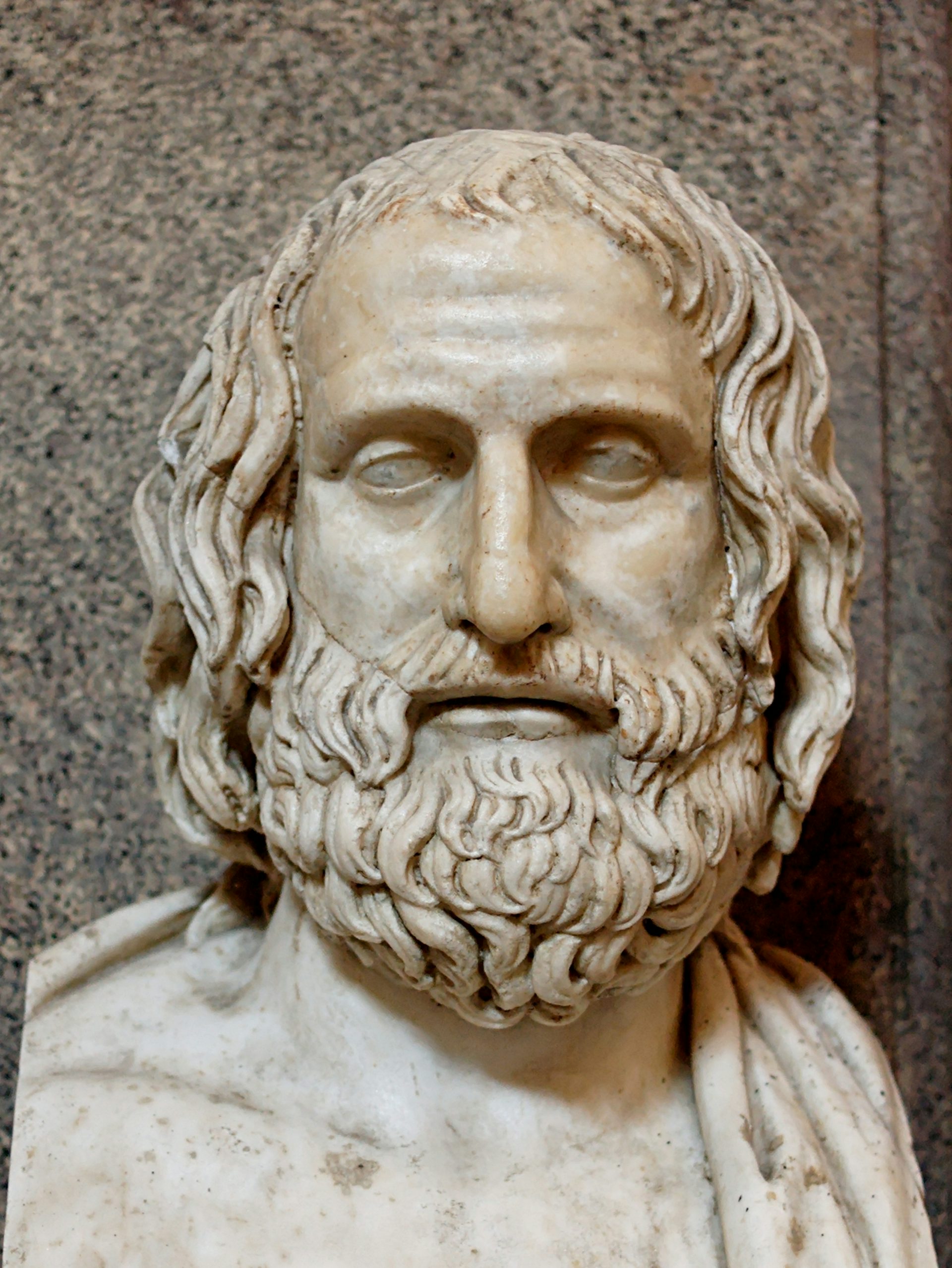

Euripides, the author of the Hecuba, was an Athenian tragedian who is usually said to have lived from around 480 BCE to 406 BCE. He was the youngest of the three canonical Athenian tragedians (the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles) and was known for exploring avant-garde, subversive, and innovative themes.

Roman bust of Euripides after a Greek original from ca. 330 BCE

Vatican Museums, Vatican / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainOver the course of his career, Euripides composed some ninety plays, eighteen of which survive in full.[1] Despite his formidable output—we have more plays by Euripides than by Aeschylus and Sophocles combined—he won only four victories at the annual Dionysia competition during his lifetime (with a fifth awarded the year after his death).[2] Yet Euripides’ popularity and literary influence have continued to grow, and some now regard him as the greatest of the Athenian tragedians.

Little is known about Euripides’ personal life; most ancient testimonia and biographies read more like fable than fact. Euripides seems to have been born on Salamis, an island near Athens, to a family of hereditary priests. He was married twice, both times unhappily, and had three sons. Ancient sources claimed that Euripides was a recluse and may have even lived alone in a cave in Salamis, though the veracity of such stories is obviously dubious. He died in 406 BCE at the court of the Macedonian king Archelaus.

Throughout his lifetime—and after his death, too—Euripides had a reputation as a challenging and controversial playwright. The comedian Aristophanes, one of his contemporaries, often mocked Euripides as an impious snob. In time, however, Euripides came to be recognized for his capable exploration of emotional realism, his innovative treatment of traditional mythology, and his persistent questioning of contemporary values.

Mythological Context

Roughly one-third of all surviving Attic tragedies center on the Trojan War and its aftermath. Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, for instance, dramatizes the murder of Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces at Troy; Sophocles’ Ajax depicts an episode from the final year of the Trojan War; and Euripides himself treated the Trojan War myth in several of his plays, including the Trojan Women and the Andromache (the latter probably produced only a few years before the Hecuba).

Euripides’ Hecuba takes place after the events described in Homer’s Iliad. At the start of the play, the Greeks have already sacked Troy, and both Hecuba (the former queen) and the other Trojan women have been reduced to slavery. Hecuba goes on to suffer a series of further tragedies. First, she loses her daughter Polyxena, who is sacrificed to the ghost of Achilles. She then discovers the body of her youngest son Polydorus, who has been murdered by his treacherous guardian Polymestor. Hecuba takes revenge on Polymestor by blinding him and killing his children, after which he predicts that she will turn into a dog.

Attic red-figure amphora showing Neoptolemus (left) killing Priam (center) as Hecuba stands by (right); attributed to the Nikoxenos Painter (ca. 500 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe myth of the sacrifice of Polyxena would have certainly been known to Euripides’ audience. It had already been narrated in the Sack of Ilium, a lost epic from around the sixth century BCE, as well as in the works of the sixth-century BCE poet Ibycus. Likewise, the ghost of Achilles was mentioned in the Nostoi, another poem from the Epic Cycle.[3]

A play titled Polyxena had also been composed by Euripides’ older contemporary Sophocles. This play, which is known today only in fragments, bears considerable similarities to Euripides’ Hecuba, but scholars disagree on which text was produced first (and thus whether Sophocles influenced Euripides or vice versa).

Finally, the sacrifice of Polyxena was depicted in a famous painting of the sack of Troy by the artist Polygnotus, displayed in the Painted Stoa in Athens around 460 BCE.

Though the myth of Polyxena was reasonably well known, Euripides introduced certain innovations to make it his own. Polyxena’s willingness to die, for instance, was probably invented by Euripides. He repeated this pattern of a young virgin of high birth bravely allowing herself to be sacrificed in exchange for a wind in his much later play Iphigenia in Aulis.

Fourth-style fresco from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii showing the sacrifice of Iphigenia (ca. 60–79 CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0The revenge plot involving the murder of Polydorus also seems to have been invented by Euripides. Polydorus had appeared in earlier literature as a son of Priam, but in these traditions his mother was Laothoe rather than Hecuba, and he was killed by Achilles during the Trojan War rather than by Polymestor after the fall of Troy.[4] Indeed, the murder of Polydorus by his host Polymestor and Hecuba’s subsequent revenge do not show up in any source prior to Euripides’ Hecuba, though the story did influence later art and literature (including Virgil’s Aeneid).

Hecuba’s transformation into a dog, predicted at the end of the play by the blinded Polymestor, may or may not have been Euripides’ invention as well. Like the story of Polydorus and Polymestor, it became a fixture of later mythical literature.

Characters

The following is a list of characters from Euripides’ Hecuba, in order of appearance:

Ghost of Polydorus (son of Hecuba and Priam)

Hecuba (widow of Priam; former queen of Troy)

Chorus (captive Trojan women)

Polyxena (daughter of Hecuba and Priam)

Odysseus (Greek king from Ithaca)

Talthybius (Greek herald)

Handmaid

Agamemnon (commander of the Greek army)

Polymestor (Thracian king)

Synopsis

The play is set on the shores of Chersonese, a Thracian colony on the west side of the Hellespont, just opposite Troy. There the Greek army is encamped, enjoying the spoils of war. The ghost of Polydorus enters and delivers the prologue, in which he explains that before the Trojan War began, his parents Hecuba and Priam sent him to live with their friend Polymestor, the king of Thrace.

After Troy fell, however, Polymestor murdered Polydorus so that he could steal the boy’s gold, then threw his body into the sea. Polydorus’ corpse now drifts through the water, but his ghost predicts that Hecuba will soon find it and give him a proper burial. This can only happen, however, if the Greeks sacrifice another one of Hecuba’s children, her daughter Polyxena, currently a captive with her in the Greek camp.

Polymnestor Kills Polydorus by Johann Wilhelm Baur (before 1642), engraving for an edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 3.0Polydorus departs as Hecuba enters. In a lyric scene, Hecuba reveals that she has had disturbing dreams about her son Polydorus and her daughter Polyxena. The Chorus of captive Trojan women arrives and reports that the Greeks have decided to sacrifice Polyxena to the ghost of the dead hero Achilles (this being the only way to secure the wind they need to blow their fleet back to Greece). Polyxena enters and learns the news, too. Though she pities her grieving mother, she herself is not sorry to die.

In the first episode, Odysseus comes to collect Polyxena, explaining that the Greeks have voted to sacrifice her. Hecuba begs him to spare her daughter, but Odysseus cannot be moved, even when Hecuba reminds him of how she once saved his life when he sneaked into Troy as a spy during the war. Polyxena accepts her fate and willingly accompanies Odysseus. In the first stasimon,[5] the Chorus wonders where in Greece they will end up as slaves.

In the second episode, the old herald Talthybius enters and tells Hecuba of how bravely Polyxena died, saying that the entire Greek army was deeply moved by her aristocratic courage. Hecuba, somewhat comforted by her daughter’s noble death, sends her handmaid to the beach for water in order to clean Polyxena’s body for burial. The Chorus sings the second stasimon, citing the voyage to Sparta in which Paris carried off Helen as the beginning of their misfortunes.

In the third episode, the handmaid returns with the devastating news that she has discovered the body of Hecuba’s son Polydorus washed up on shore. Hecuba surmises that Polydorus was murdered by his guardian Polymestor and decides to seek revenge. She even asks Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek army, to help her. Though Agamemnon is unable to aid Hecuba openly, he agrees to buy her the time she needs to put her plans into motion. In the third stasimon, the Chorus describes the night Troy fell, when their husbands were killed and they became slaves.

The fourth episode and exodus center on Hecuba’s revenge on Polymestor. Polymestor arrives with his sons, and Hecuba lures them into her tent with the promise of more treasure. Cries of anguish can be heard from within the tent as the Chorus, still outside, sings of the power of justice. Polymestor emerges, revealing that he has been blinded, while his sons have been torn apart. He appeals to Agamemnon, who makes a show of listening to both his and Hecuba’s cases before determining that Polymestor has been fairly punished for his misdeeds.

Polymestor is furious and warns Hecuba and Agamemnon that they will both come to a sorry end: he foretells that Hecuba will be transformed into a dog and leap into the sea, while Agamemnon (and his new concubine Cassandra) will be murdered by his wife Clytemnestra as soon as they reach Greece. Agamemnon has Polymestor marooned on a desert island. Just then, the winds begin to blow, and Agamemnon commands the army to at last prepare for departure.

Hecuba Kills Polymestor by Giuseppe Maria Crespi (first half of the 18th century)

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, BrusselsPublic DomainStyle and Composition

Certain stylistic and metrical features of the Hecuba suggest that it was composed in the second half of the 420s BCE. We can assume that, like Euripides’ other plays, the Hecuba was performed as part of a tragic tetralogy (consisting of three tragedies and one satyr play) at the dramatic competition held during the annual Dionysia festival. However, we do not have any details about the original performance, nor do we know which other plays made up the remainder of the tetralogy.

Themes

Structurally, the Hecuba can be divided into two distinct parts. The first part takes the form of a “suppliant” plot, with the character of Hecuba pleading for the life of her daughter Polyxena, who is to be sacrificed. The second part is a “revenge” plot, with Hecuba taking vengeance on the Thracian king Polymestor for murdering her son Polydorus.

This structural dualism, once criticized by scholars for disrupting the play’s unity, is echoed in other doublings throughout the play. There are thus two ghosts in the Hecuba (Polydorus and Achilles), two children of Hecuba who are killed (Polyxena and Polydorus), and two Greek kings whom Hecuba must ask for help (Odysseus and Agamemnon). Indeed, the play’s entire conception of character (especially the character of Hecuba) is marked by dualism.

Perhaps the most obvious and central theme of the play is suffering, as well as endurance in the face of that suffering. Hecuba is presented as a paragon of misery: her city has been sacked, she has been enslaved, and her husband and many of her children have been killed. Her misfortunes are so unbearable precisely because she was once so happy—the queen of a rich city and the mother of many noble children. Hecuba thus exemplifies the terrible changeability of fortune.

Hecuba and Polyxena by Merry-Joseph Blondel (after 1814)

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainHecuba, her daughter Polyxena, and the Chorus of captive Trojan women all underscore the plight of female victims of war, who are ripped from their homelands and enslaved after losing their husbands and children. Polyxena prefers death to this kind of life. Hecuba, on the other hand, learns to endure her suffering—indeed, the worse her situation becomes, the more her resilience grows.

The Hecuba, like many of Euripides’ plays, is also a study in the degeneration or transformation of character. Hecuba in particular changes dramatically over the course of the play. At first she is helpless, a passive victim of fate. But Polyxena’s noble death inspires her to nobly endure her own suffering. By the end of the play, she carries out a violent and animalistic revenge on Polymestor, culminating in Polymestor’s prediction that she will literally turn into an animal. Hecuba’s dualism—and the dualism exhibited, on a smaller scale, by other characters (including the duplicitous Odysseus and Polymestor)—reflects the overarching dualism of the play.

Nobility and heroism also emerge as key themes in the play. Polyxena especially shows great courage when she willingly meets her death, and her actions are interpreted by the Chorus as an example of the inborn nobility of the aristocracy. Polyxena, like her queenly mother, is presented as inherently dignified, a person who is free by nature and who therefore cannot truly be enslaved. (It is unclear how the democratic Athenians of Euripides’ day would have felt about this aristocratic heroine and her implicitly undemocratic ideals.)

Rape of Polyxena by Pio Fedi (1855–1865)

Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence / Mary HarrschCC BY-SA 4.0Finally, the play explores themes of vengeance and justice, which come to the fore above all in Hecuba’s revenge on Polymestor. But the question remains as to whether her violence is justified. Indeed, scholars have long debated whether Athenian audiences would have condoned Hecuba’s actions or not.

Reception

Euripides’ Hecuba has passed in and out of favor over the centuries. In antiquity, the play appears to have been quite popular. Soon after it was produced, depictions of Polyxena’s sacrifice began to proliferate in the visual arts of Athens, specifically in vase paintings. Elements of the plot were reworked by later Roman poets, including Virgil in Book 3 of his Aeneid, Ovid in Book 13 of his Metamorphoses, and Seneca in his Trojan Women.

Part of the reason for the play’s popularity seems to have been its quotability: the characters are full of pithy reflections on fate, the changeability of fortune, and human nature. Indeed, it was probably this quotability that led to the Hecuba’s inclusion in the “Euripidean triad”—a collection of three plays by Euripides that were commonly used in education during the Byzantine period. (Alphabetically, the Hecuba was also the first in the triad and so was usually the first to be read.)

The Death of Polydorus, tapestry by unknown artist (17th century)

Musée des Beaux-Arts, LyonCC BY-SA 3.0The play remained popular in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, when its themes of vengeance and bloodshed enjoyed wide popular appeal. But by the seventeenth century, these same qualities had fallen out of favor, and until the twentieth century the Hecuba was often regarded in the West as the worst surviving Greek tragedy.[6]

More recently, the Hecuba has regained some of its popularity, with many new translations and performances now appearing.

Translations

Translations of the Hecuba are usually found in volumes of Euripides’ collected plays. The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Coleridge, E. P., trans. The Plays of Euripides. Vol. 1. 9th ed. New York: Random House, 1938: Prose translation in Coleridge’s edition of the collected works of Euripides; can be viewed online through the Perseus Project.

Collard, Christopher, ed. and trans. Euripides: Hecuba. Aris and Phillips Classical Texts. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1991: Prose translation with facing Greek text; keyed to a commentary directed at beginners.

Kovacs, David, ed. and trans. Euripides, Vol. 2: Children of Heracles, Hippolytus, Andromache, Hecuba. Loeb Classical Library 484. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995: Accurate prose translation with facing Greek text.

Davie, John, trans. Electra and Other Plays. Edited by Richard B. Rutherford. London: Penguin, 1998: Accurate and idiomatic prose translation, best suited to more knowledgeable readers.

Morwood, James, trans. Euripides: Heracles and Other Plays. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: Accurate and idiomatic prose translation with useful notes and references.

Carson, Anne, trans. Grief Lessons: Four Plays by Euripides. New York: NYRB Classics, 2008: Contains verse translations of the Hecuba as well as the Alcestis, Heracles, and Hippolytus.

Arrowsmith, William, trans. Euripides II: Andromache, Hecuba, The Suppliant Women, Electra. 3rd ed. Edited by Mark Griffith and Glenn W. Most. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013: Readable and accurate verse translation with a basic introduction and notes (originally published in 1958).