Graeae

Perseus and the Graeae by Edward Burne Jones (1892)

Staatsgalerie, StuttgartPublic DomainIntroduction

The Graeae, daughters of Phorcys and Ceto, were creatures who appeared as haggard old women. Their names were usually recorded as Pemphredo, Enyo, and Deino (though in some traditions, there were only two Graeae instead of three).[1] They made their home in a remote corner of the world, not far from their fearsome sisters, the Gorgons. The Graeae’s withered appearance was made even more grotesque by the fact that they possessed only one eye and one tooth, which they shared among themselves.

When Perseus set out to kill the Gorgon Medusa, he first came to the lair of the Graeae. There, he stole the sisters’ single eye, rendering them blind so they would help him on his quest.

Etymology

The etymology of “Graeae” (Greek Γραῖαι, translit. Graîai) is relatively straightforward. It comes from the Greek word γραῖα (graîa), meaning “old woman, gray,” a word that is itself derived from the Indo-European root *ǵerh₂-, “to grow old” (via Proto-Greek, *gera-/grau-iu).[2]

Various names were attached to the individual Graeae. Two of them were always called Pemphredo (Greek Πεμφρηδώ, translit. Pemphrēdṓ)[3] and Enyo (Greek Ἐνυώ, translit. Enyṓ); the third sister, added by some sources, was called either Deino (Greek Δεινώ, translit. Deinṓ), Perso (Greek Περσώ, translit. Persṓ), or Persis (Περσίς, translit. Persís).

The etymologies of these individual names are uncertain. Pemphredo shared her name with a kind of wasp (πεμφρηδών, pemphrēdṓn). The etymology of Enyo is completely mysterious but is seemingly connected to Enyalius, one of the names of the war god Ares. Deino is more straightforward, meaning something like “the terrible one,” while Perso or Persis translates to “the destroyer.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Graeae Γραῖαι (Graîai) Phonetic

IPA

[GREE-ee] /ˈgri i/

Other Names and Epithets

Along with the Gorgons, their even more terrifying sisters, the Graeae were sometimes known as the Phorcides (Greek Φορκίδες, translit. Phorkídes), meaning “daughters of Phorcys.”

Ancient authors such as Hesiod gave the Graeae (both individually and collectively) the kinds of epithets that were typical of goddesses. These included καλλιπάρηος (kallipárēos, “fair-cheeked”), εὔπεπλος (eúpeplos, “finely-robed”), and κροκόπεπλος (krokópeplos, “saffron-robed”)[4]—surprising names considering the rather grotesque appearance usually associated with the creatures.

Attributes

Catalogue

In ancient sources, the number of Graeae varied between two[5] and three.[6] Hesiod, who knew of only two Graeae, gave their names as Pemphredo and Enyo.[7] All subsequent sources seem to have retained these two names, though some added a third sister, whose identity varied; she was most often called Deino,[8] but some authorities dubbed her Perso[9] or Persis[10] instead.

Locales

Ancient writers usually said that the Graeae lived in a remote part of the world. According to Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, they could be found in the mysterious “Plain of Cisthene,” somewhere in the Far East, not far from the Gorgons. There, “neither does the sun with his beams look down upon them, nor ever the nightly moon.”[11]

Other sources placed the abode of the Graeae elsewhere. Nonnus kept their home in the East, saying that they lived on an island beyond India.[12] Ovid, on the other hand, seems to have imagined them in the West, in a “vale beneath cold Atlas…with aspiring mountains fenc’d around.”[13]

Appearance

The Graeae were old and gray-haired from birth.[14] The tragedian Aeschylus described them as swan-formed, but it is unclear whether this was a reference to their physical shape or simply to the pale color of their hair.[15] They were invariably depicted as ancient and long-lived and may have been immortal.[16]

The Graeae possessed just one eye and one tooth, which they shared.[17] This suggests that they were usually thought of as old, ugly hags. However, there were exceptions to this image: Hesiod, for example, described them as “fair-cheeked” and beautifully dressed (see above), and ancient artists sometimes followed his lead (see below).

Iconography

In ancient art, the Graeae were often shown as old and ugly, but they sometimes appeared as young, beautiful maidens.[18] In the late fifth century BCE, vase painters began producing representations of the mythical scene in which their one eye was stolen by Perseus.[19]

Family

The Graeae were among the fearsome offspring of Phorcys and Ceto, early Greek deities connected with the sea.[20] They had a host of siblings no less monstrous than they were. These included the terrible Gorgons (Sthenno, Euryale, and Medusa),[21] as well as, in some traditions, the dragon Ladon (guardian of the Garden of the Hesperides),[22] the snake-monster Echidna,[23] the Hesperides,[24] Scylla,[25] and Thoosa (mother of the Cyclops Polyphemus).[26]

Mythology

Origins

The origins of the Graeae are obscure. It was once thought that they first emerged as sea goddesses (a fitting theory, given that their parents were early sea deities). But recent scholars have favored a different interpretation, in which the Graeae (like their sisters the Gorgons) were originally sky goddesses, whose swan-like shape and pale hair represented storm clouds.[27]

Their Sister’s Keepers: Perseus and Medusa

The Graeae were known above all for their connection with Perseus and his heroic quest to slay Medusa. In this popular tale, Perseus had been sent to kill Medusa, the only Gorgon who was mortal—a seemingly impossible task, as Medusa’s gaze turned all who looked upon her to stone. Perseus, however, was no ordinary man: he was the son of Zeus himself, and the gods rallied to help him defeat his foe.

But Perseus also needed the help of the Graeae—a difficult thing to obtain, given that Medusa was their sister.

There are different versions of what Perseus needed from the Graeae. In one version—probably the more familiar one—the hero needed to locate a group of nymphs who were in possession of winged sandals, a cap of invisibility, and a magical bag (the kibisis) that could hold Medusa’s dangerous head—the tools required to face the Gorgon. But only the Graeae knew where Perseus could find these nymphs.

To force the Graeae to reveal the location, Perseus stole the one eye that they shared among themselves: as the Graeae were exchanging the precious organ, Perseus darted in and snatched it away. He then refused to give it back until the sisters told him what he needed to know.[28]

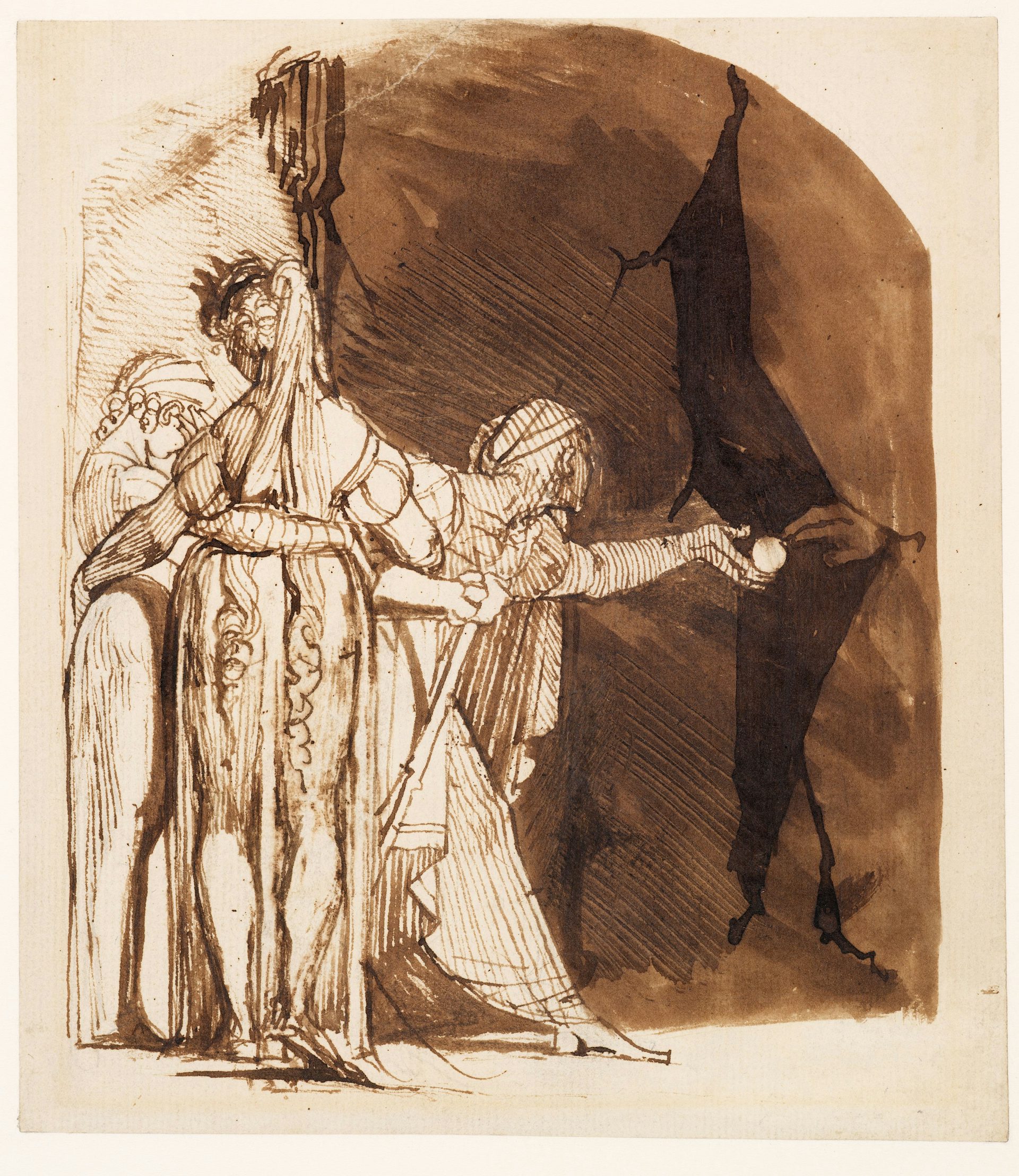

Perseus Returning the Eye to the Graeae by Henri Fuseli (1790–1800)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn another version, Perseus was able to acquire the tools he needed (sandals, cap, and bag) with the help of the gods. But the Graeae stood guard at the entrance to the land of the Gorgons. Thus, to prevent the Graeae from helping their sisters, Perseus stole their eye and threw it into Lake Tritonis.[29]

Pop Culture

The Graeae make only occasional appearances in modern pop culture. In Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, they adjust to the modern world as operators of a taxi firm in New York City. They are best remembered for the one eye and one tooth they shared. In Disney’s Hercules, this aspect of their myth is extended to the three Fates, who, like the Graeae, must also share a single eye.