Ganesha

Overview

Ganesha, the son of the powerful gods Shiva and Parvati, is one of the most popular gods in modern Hinduism and is widely worshipped throughout South and Southeast Asia. Even people in predominantly Buddhist countries, such as Thailand, devoutly worship the god.

As the remover of obstacles, worshippers call on him every day for matters great and small. His popularity far exceeds the number of stories about him, as there are relatively few myths of Ganesha compared to other popular figures like Vishnu and Shiva.

He has the head of an elephant and rides upon a mouse. This portly god often appears in iconography with four arms holding a bowl of modaks (sweet dumplings), his broken tusk, and an axe, noose, or trident. Statues commonly portray him with a hand raised, palm facing outward in abhayamudra, a gesture meant to dispel fear.

Etymology

The etymology of “Ganesha” is straightforward: the name is a compound word formed of two parts. The first, gaṇa (गण), in its simplest sense refers to a troop, multitude, gang, or tribe.[1] In this context, however, it refers to a group of lesser gods who have devoted themselves to Shiva and Parvati as servants and warriors. The second component, isha (ईश), means “lord, master, husband, ruler.” In this way, “Ganesha” simply means that he is lord of Shiva’s attendants, or captain of the guard.[2]

“Ganapati” is another popular name for Ganesha and is similar in meaning: pati (पति) also translates as “lord, master.”

Pronunciation

English

Sanskrit

Ganesha गणेश Phonetic

IPA

[Guh-NAY-shuh] / gəˈɳe ʃə /

Titles and Epithets

Ekadanta (एकदन्त), “One Tusk”

Ganapati (गणपति), “Lord of Ganas”

Ganeshvara (गणेश्वर), “Lord of Ganas”

Lambodara (लम्बोदर), “Dangling Belly”

Vighneshvara (विघ्नेश्वर), “Lord of Obstacles”

Vinayaka (विनायक), “Remover [of Obstacles]”

Attributes

Owing to his love of sweets, Ganesha is usually depicted as having a pot belly, with his elephant’s trunk tilted toward a plate of sweet modak buns. In his hands he often bears some combination of a trident, noose, goad, or axe; his broken tusk; a lotus; and prayer beads. With a free hand he sometimes gestures in abhayamudra. His vehicle is a small mouse.

Seated Ganesha holding a bag of modaks, his broken tusk, an elephant goad, and snakes. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ca. 14th–15th century.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainDomains

Because Ganesha broke off his own tusk so that he could continue writing the Mahabharata, he is considered a god of learning, writing, and poetry. Although he displays the great martial prowess of his father, Shiva, and is able to fend off armies of gods and demons, he is not primarily known as a warrior. Above all else, worshippers pray to him as a remover of obstacles both mundane and extraordinary.

Family

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

- Parvati (Sati)

Siblings

Brother

Consorts

Wives

- Siddhi

- Buddhi

Children

Sons

- Kshema

- Labha

Mythology

Origins

Scholars in the early twentieth century identified Ganesha as a natural progression from a rural harvest god, with Gupte arguing that Ganesha once bore the name Mushaka Vahan, “He Whose Vehicle Is a Mouse,” or “Mouse Rider.”[3] As the rat is always a pest for farmers and agricultural workers, Ganesha’s use of a rat as a vehicle symbolized that the god had conquered the rodent and was therefore a godsend for farmers. Gupte also argues that Ganesha’s nickname, Ekadanta (“One Tooth”), originally meant a scythe or plowshare.

Thani-Nayagam disagrees with this characterization and instead identifies Ganesha as a fusion of several different pre-Aryan malign spirits who inhabited forests and jungles.[4] As such, he was a god who had to be worshipped and appeased before any of the other gods in order to avoid obstacles and supernatural catastrophes.

Other explanations abound, including the possibility that Ganesha began as a Dravidian sun god or that he was originally an aspect of Shiva or his Vedic forebear, Rudra.

S. M. Michael traces the term gaṇapati throughout Vedic and Puranic literature and concludes that while it originally referred to a troublemaker and “catastrophe incarnate,” it came to mean a remover of obstacles around the fifth or sixth century CE.[5] He suggests that warfare between tribes was the cause for this transformation: a tribe whose patron god was an elephant conquered a nearby tribe whose patron deity was a rat. Ganesha riding on a rat then symbolized the tribe’s conquest of their neighbors and elevated him to a benevolent god.

Although Ganesha is undoubtedly one of the most popular gods of Hinduism today, there are remarkably few stories featuring him as a central character. What stories there are have a number of variants in Hindu mythology.

Birth and Beheading

The reason for Ganesha’s beheading differs greatly depending on the tale, but most agree that it happened not long after his birth. All the myths state that either Parvati alone or Parvati together with Shiva gave birth to him, while the beheading is blamed on Shiva or the god Shani, who corresponds to the planet Saturn.

Birth by Parvati Alone and Beheading by Shiva

The most well-known version of Ganesha’s birth and beheading comes from the Shiva Purana. Parvati was enjoying a relaxing stretch of time at home while Shiva was away in the mountains on one of his many meditation retreats.[6] While talking with her friends Jaya and Vijaya, she lamented that the servants, soldiers, and attendants that guarded their house were all Shiva’s men, subservient to him alone rather than to both of them.

How wonderful it would be, Jaya and Vijaya said, to have at least one person they could call their own who was not under Shiva’s thumb. But they would have to make one.

Soon after, Shiva came into her bathroom as she was bathing, and the goddess stood up, shocked that no one had stopped him. She would have to fix this, she thought, and resolved to create a guardian who would watch her door and protect her without a single thought to Shiva. The next time she took a bath, she scuffed off some of the dirt and fashioned the boy Ganesha out of it. In this way, Ganesha was born without any help from Shiva at all.

Parvati rejoiced, dressed him in fine clothes and ornaments, and told him, “You are my son. You are my own. I have none else to call my own.”[7] The boy bowed respectfully and asked what duties he was to perform. She told him to guard her door and to let no one in without her permission. To carry out these orders, she gave him a staff to fight off anyone who tried to intrude upon her chambers.

Not long after, Shiva came home from his meditation and found the young god, of huge stature even then, blocking his path and refusing his entrance into Parvati’s chambers. No one, Ganesha said, not even Shiva himself, may enter without his mother’s permission. Pressing his luck even further, Ganesha began to shoo his father away by whacking him with a staff. Shiva was confused and grew angry at being denied entrance to his wife’s chambers.

Even when Shiva announced who he was and proclaimed that this was his own house, Ganesha did not allow him through. He simply beat his father again with his staff as if Shiva were a common vagabond. With both their tempers rising, Shiva backed away and had his Ganas (attendants and warriors) ask Ganesha for the meaning of all this.

Approaching the young god, they said that they, as Ganas, were the real doorkeepers of the house, but since they recognized him as a Gana himself, they would not kill him. They accused the boy of being a jackal sitting on a lion’s throne—merely playing at being tough. Shiva insisted that they remove the haughty boy by force, but they were unable to move him.

Ganesha’s words were calm and certain: Shiva had ordered his warriors to make way for his entrance, while Parvati had ordered her servant to stop him. These two orders could not be reconciled. They were at an impasse, and he would not allow anyone through.

At last the matter came to real blows as the Ganas left and returned arrayed for war. Shiva’s mount, Nandi, grabbed Ganesha’s leg as the thousands of Ganas rushed at him with a great gnashing of teeth. But Ganesha was able to wrench his leg free and smash the Ganas with a heavy iron club, shattering hands and legs and fracturing kneecaps and spines. Before long, they fled like frightened deer, and Ganesha went back to his station. He had stood against thousands unfazed.

Attracted to the sounds of battle, Indra, Vishnu, and all the gods came to see what was the matter and bowed before Shiva. Trusting in the creator god Brahma’s great wisdom and skill in debate, Shiva sent him to negotiate. But Ganesha was in no mood: he brandished his iron club at Brahma and shooed him away just as the creator god assured him that he sought a peaceful solution to their problem.

Now truly incensed, Shiva summoned all his heavenly armies with their ghosts, spirits, and frightful beasts and rushed at Ganesha a second time. But these too were beaten back. Even all the gods together failed to break the boy, and the heavens, hells, and earth shook with their battle. Lightning-hurling Indra and discus-bearing Vishnu fled along with the others.

They warred with the boy a third time, now with Shiva at the head of their army. Ganesha struck down his father’s trident, cutting Shiva’s powerful bow and five of his hands along with it. The gods’ efforts seemed doomed to fail as Ganesha hurled his club and struck Vishnu, but Shiva seized the opportunity and cleaved the weaponless boy’s head with his trident.

There was little time to celebrate their victory, however; just as the gods began to shout for joy, Parvati cried out in despair and grief at the death of her son. “O what shall I do?” she wailed. “Where shall I go? Alas, great misery has befallen me. How can this misery, this great misery be dispelled now? My son has been killed by all the gods and the Gaṇas. I shall destroy them all or create a deluge.”[8]

Crying out in agony, she then created hundreds of thousands of Shaktis, powerful heavenly warriors, and commanded them to wreak havoc on the gods and all the worlds and heavens. Her deluge was unleashed. By the Shaktis’ fury, worlds and gods burned as if made of dried grass.

Fearing that the assault might cause the cosmos to end prematurely, the gods held a meeting to decide what to do. Parvati was adamant: only her son’s life, properly restored, would end the destruction.

All versions of the myth agree on the ending: Shiva told his followers to travel north and bring back the head of whomever they found first, which happened to be an ordinary elephant. With a sprinkle of holy water and the recitation of Vedic passages, the severed head attached to the body, and Ganesha sprang up full of life once more.

For his bravery and service, he was named “Ganesha,” or lord of the Ganas.

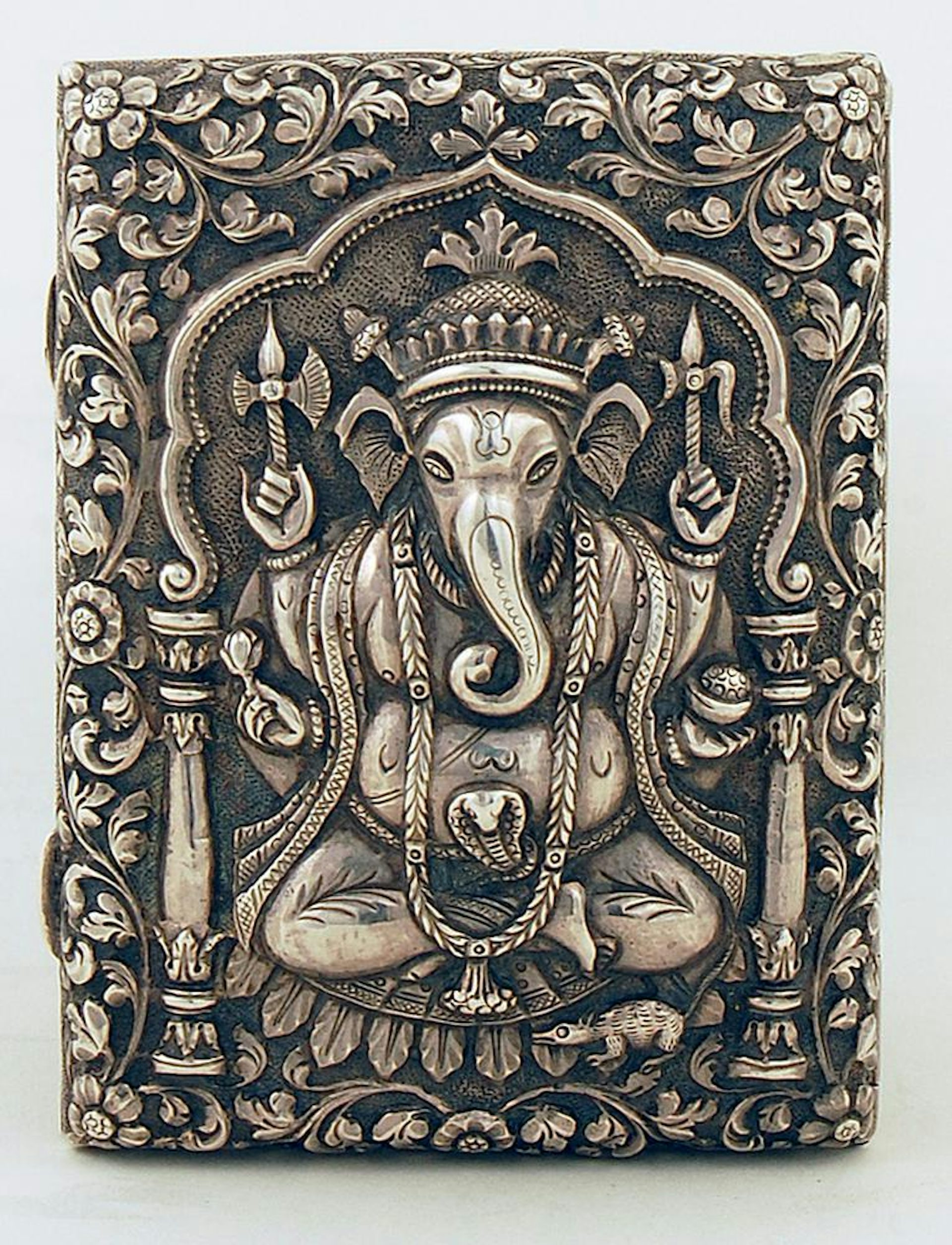

Calling card case decorated with Ganesha bearing a lotus, bowl of modaks, an axe, and a goad. Mouse vehicle visible underneath. British Museum, London, ca. 1880.

Trustees of the British MuseumPublic DomainBirth by Parvati and Beheading by Shani

According to the Brihaddharma Purana, Ganesha’s birth was a spontaneous miracle. The story goes that after Shiva and Parvati married, Parvati wanted very badly to have a child and to feel its kisses. She tried to persuade her husband by saying that a man without a son—even a god as powerful as he—would have nobody to perform rituals and religious rites after his death. She then asked Shiva to make love to her that very day to have a child.

Shiva, ever the ascetic god, refused and said that since he was not truly a family man at heart, he had no desire for a child, or even a wife. A wife is a ball-and-chain, he said, and a child is a noose. Moreover, since he was among the foremost of gods, he would never die and so had no need of a son to perform the necessary rites for him.

But Parvati was dead set in her desire. She promised to take care of the boy herself and raise him as a Yogi like his father, never to marry. Thus, Shiva would have no descendants apart from him to worry about. He could go back to his austerities and asceticism once they had a child. But the great god of destruction only stormed away, leaving his wife to weep and brood. It was only when her two friends, Jaya and Vijaya, talked with Shiva that he agreed to have a child.

However, Shiva was still opposed to having children the usual way. Being a wily and sometimes playful god, he took some of Parvati’s clothing and fashioned them in the shape of a baby. “There you go!” teased Shiva. “Don’t be sad now. You can have your child’s kisses.” And he told her to hug and kiss the bundle of cloth. His wife brooded over his words but embraced the bundle despite his joking.

To their amazement, as soon as she treated the bundle as a real child and held it to her breast, it indeed came to life. As the mother and child shared their first moments together, Parvati was overcome with the happiness of her child’s kisses.

Shiva, for his part, was less amazed with having a child than with how it came to life in the first place. He had only intended to tease his wife, but now he truly had a son, a noose. Inspecting the boy all over for auspicious or inauspicious signs, as is traditional in Indian folklore, he found an ill omen. The boy was fated to die young, he said, because the god Shani (Saturn) had glanced upon his face. With that, the boy’s head fell clean off, seemingly on its own, and the lifeless body fell limp in his arms.

The palace erupted with Parvati’s cries at the loss of her newborn baby, but Shiva calmed her. Acknowledging that nothing was more sorrowful than losing a son, he promised to bring the baby back somehow. Merely placing the boy’s head back on his shoulders accomplished nothing. But a voice called out from above, telling Shiva that since his child’s head was facing north when it fell off, he should travel north, bring whatever head he found, and attach it to the baby.

Rather than go himself, Shiva sent his mount, Nandi, who in this tale is more of a man-bull hybrid than the usual bull depicted in iconography. After travelling for some time, the bull came across the heavenly elephant Airavata, the mount of Indra. He drew back his weapon and was about to behead the beast when Indra himself came to his mount’s defense and attacked with trident, mace, and lightning.

Nandi had the better of the fight and lopped off the elephant’s head with a single blow. But in swinging with all his might, Nandi also chopped off one of the elephant’s tusks. In a flash, he was away again to the house of his master, leaving the god Indra to mourn the loss of Airavata.

The plan worked, for as soon as Shiva placed Airavata’s head on the boy’s neck, he sprang to life once more. They rejoiced at having their child again, and all the gods came to bless the child with gifts and honors. Indra, meanwhile, grieved and told Shiva all that had happened. In return for the loss of the elephant’s head, Shiva said that during the churning of the cosmic ocean, which had not yet come to pass, Airavata would spring up out of the ocean, fully formed once more. Until then, Shiva gave Indra an immortal bull.[9]

This version of the story stands in clear contrast to other myths in that Parvati assures Shiva that Ganesha will be a childless ascetic. In at least one story, it is clear that Ganesha marries twice and has two children, although little is known of them.

Birth by Shiva and Parvati Together

Another version of Ganesha’s birth is told in the Linga Purana and pays special attention to Ganesha’s association with obstacles and impediments. At one time, the devas (gods) and daityas (demons or titans) were engrossed in their never-ending war for supremacy. The devas complained to Shiva that he granted the daityas whatever they wished when they worshipped him. Eager for the same benefits, they prostrated themselves before him and asked for a favor that would impede the daityas in their war effort.

Moved by their devotion and worship, Shiva at once created Ganesha: he leapt into the womb of his wife, Parvati, and out sprang his son. This version differs from others in that Ganesha was born with the head of an elephant straightaway rather than having his head replaced. Sages threw flower petals over the babe, and Shiva held him in his arms and proclaimed Ganesha the destroyer of the daityas.

Shiva said that Ganesha was to help the Brahmins recite the Vedas (emphasizing his role as god of knowledge and studying). He was also ordered to block the efforts of—or even kill—those who strayed from the caste system by performing Vedic rites without being born into the Brahmin caste. Shiva noted that whoever sought benefits in life without worshipping his son would have impediments placed in their path. Lastly, Shiva laid out those offerings appropriate for Ganesha’s worship: sweets, flowers, and incense.

This version of the story identifies Ganesha as a defender of the Brahmanical social order, but also a punisher of those who did not perform the duties of their caste. It also paints a curious picture of Ganesha as a god who creates obstacles rather than removing them.[10]

Beheading by Shani

The account of Ganesha’s beheading as told in the Shiva Purana begins with a dialogue between the sage Narada and the mighty god Brahma. After hearing stories of Karttikeya, Ganesha’s brother, Narada asks to hear the birth story of Ganesha. Brahma himself acknowledges that this story has several versions, which change depending on the kalpa, or age.

Indian mythology characterizes existence as cyclical, even on the cosmic scale, so that the same events may pan out slightly differently in different eras. The story told above in which Shiva beheads his son occurs in the shvetakalpa. But Brahma says that in another kalpa, it was Shani, the deified figure of the planet Saturn, who beheaded the god.

Shani was also known as Kruradrish (क्रूरदृश्), “The Evil-Sighted One,” for he had the power to viciously harm whomever he gazed upon. The story goes that after Ganesha’s birth, Parvati was proudly showing off her son to the various gods and asked Shani to look at the boy. He reluctantly did, and though he glanced for only a moment, the boy’s head immediately turned to ashes. The creator god Brahma then told Parvati to replace the head with whatever she could find first, which was an elephant’s head.[11]

Losing His Tusk

Stories also vary on the matter of how Ganesha lost his tusk. We have already seen one account in which Shiva’s bull Nandi was responsible for the loss before Ganesha ever received his elephant head. The story in which Shiva dives into Parvati’s womb says that Ganesha was born with only one to begin with. But the most well-known story involves Ganesha severing the tusk himself and firmly establishes Ganesha’s character as a patron of the arts and learning.

At one time, the sage Vyasa set out to dictate the massive epic poem the Mahabharata, centered around the struggle of the Kauravas and the Pandavas for their father’s throne. Ganesha agreed to serve as scribe for the work as Vyasa recited. But because he was eager to finish the job quickly, he told the sage that he would only write if Vyasa was able to dictate without any breaks or pauses in the recitation.

The sage agreed but told Ganesha only to write if he understood the meaning of the verses precisely. Whenever Vyasa gave a particularly difficult or complex verse, the god had to pause and ask for an explanation. This trick gave the sage time to think of future verses. But eventually, their pace grew so furious that Ganesha’s pen broke. Rather than pause the narrative, he snapped off his own tusk to use as a pen. For this reason, Ganesha is a popular god among artists, students, and writers.

The Race Around The World

Ganesha is a wily god who has no difficulty using his cleverness to beat stronger and faster opponents, even his own brother, Skanda.[12] According to the Shiva Purana, both Ganesha and Skanda desired to get married upon reaching adulthood, and each wanted to marry before his brother. Growing tired of their sons’ endless bickering, Shiva and Parvati summoned them and proposed a contest.

As both Ganesha and Skanda were very dear to them, they decided that whichever one could travel around the world fastest would have the honor of marrying first. With that, the race was on, and Skanda immediately sped away across the world, fast as lightning. As the stronger and faster of the two, he was confident that he would soon be married.

But Ganesha was the wiser one, and he pondered what to do. He knew that he was slower than his powerful brother and would only get so far before Skanda beat him. So he came up with a plan.

After going to his own house and ritually cleaning himself, he returned to his parents, set out cushions for them, and asked them to accept his worship. He reverently circled his parents seven times and bowed seven times, saluting his parents with hands together. Ever the devious one, he then announced that he had won the race and expected his marriage to begin soon.

“But what is the meaning of this?” Shiva and Parvati said. “Your brother has already left! You must leave quickly if you are to have any hope of winning the race.”

Ganesha was coy and said, “But father and mother, I have just circled the world seven times!” He cited the Vedas, which say that children who worship their parents will reap all the fruits of those who traverse the world, while those who go on a pilgrimage and leave their parents at home will suffer as if they had murdered their parents.

Pushing the matter further, Ganesha said that if Shiva and Parvati refused his marriage, then they would be proving the Vedas themselves false. With all the pride they could muster, his parents praised his wit and tenacity and agreed that he had won the race fairly. His marriage would take place soon.[13]

Prajapati Vishvarupa offered his two daughters, Siddhi and Buddhi, in marriage, and with them Ganesha had two sons: Kshema and Labha. But Ganesha’s brother, Skanda, was greatly distressed at having lost the race so underhandedly, causing a lasting rift between Skanda and the rest of his family.

Worship

Festivals and/or Holidays

The ten-day festival of Ganesh Chaturthi celebrates the god’s birth and descent from the Himalayas with his mother, Parvati. As many as 150,000 clay idols are made, ranging from the small and hand-held to gigantic, 20-meter-tall statues. The faithful decorate the idols with vibrant paints and garlands and leave offerings of sweet fruits and modaks filled with coconut. Especially popular in Pune and Mumbai, the celebration culminates on the tenth day, when several thousand clay Ganesha idols are carried down into the ocean and left to dissolve.

Offerings of bananas and melons are placed on the idol of Ganesha for Ganesh Chaturthi.

Thejas PanarkandyCC0Temples

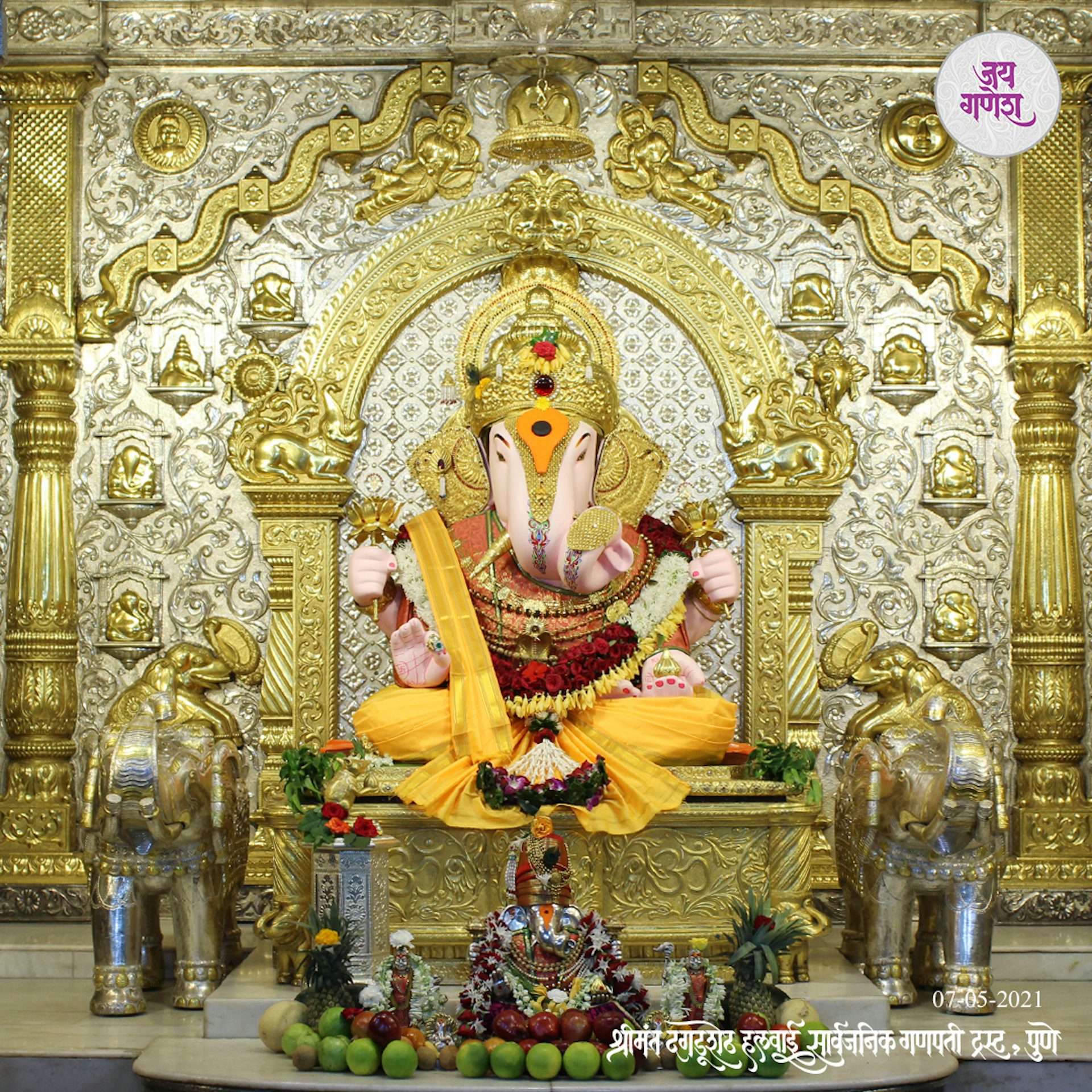

Among the thousands of temples and small shrines dedicated to Ganesha, two of the most famous and lavishly decorated ones in South Asia are the Shri Siddhivinayak temple in Mumbai and the Shreemant Dagdusheth Halwai Ganapati temple in Pune.

Richly ornamented statue of Ganesha flanked by elephants at the Shreemant Dagdusheth Halwai Ganapati temple.

Dagdusheth Ganapti templePublic DomainPop Culture

As perhaps the most popular god in modern Hinduism, Ganesha appears everywhere from street art to temples, movies, and television shows for children. The live-action television series Vighnaharta Ganesha began in 2017 and now includes over 750 episodes centered around the mythological adventures of Ganesha.