Frigg

Overview

Best known as the wife of Odin, Frigg was a ruling member of the Aesir tribe and the queen of all Norse deities. Despite her leading status, Frigg’s place in Norse mythology remains uncertain. She was rarely discussed in primary sources, and her precise characteristics and personality remain unclear. Frigg held power over many areas of life, and was associated with fertility, marriage and the household, love and sexuality, and wisdom and prophecy.

Historically, most scholars considered Frigg to be an aspect of Freya, a goddess of the Vanir tribe, as her basic characteristics aligned closely with those of Frigg. Like Freya, Frigg was a völva, or practitioner of the magical art of seidr, and sought to divine or alter the future through ritual. While the two goddesses were often presented as separate deities, they likely evolved from a single deity whose personality oscillated violently enough to merit separate identities. Freya, for instance, was known for sexual indulgence and promiscuity; Frigg, meanwhile, was more conservative in her sexual morality.[1]

Etymology

The name “Frigg” was derived from the Proto-Germanic *frijaz, meaning “beloved, dear.” The English day of the week "Friday," may be related to the goddess by way of the Old English word Frīġedæġ, meaning “Frigg’s day.”

Attributes

As wife of Odin, Frigg was the undisputed queen of the Norse gods. In art from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Frigg was often depicted sitting on a throne or holding a commanding pose.

“Frigg and her Maidens,” from Wägner andAnson, Asgard and the Gods: the Tales and Traditions of Our Northern Ancestors (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1902), 97. Translated from Wägner's Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden.

duncan1890 / iStockFrigg dwelled in Fensalir, a watery realm that likely took the form of a bog, marsh, or wetlands. She owned an ashen box called an eski, which the goddess Fulla toted around for her; the box’s contents were unknown. She was also known to have a set of falcon plumes that the gods, notably Loki, used to shapeshift into bird form.

Family

Frigg’s parentage remains unknown. Later in life, Frigg married Odin, with whom she had Hermod and Baldur, the shining deity known as the wisest of the Aesir gods.

Family Tree

Mythology

Frigg played a prominent role in two Norse myths, featured in the Grímnismál of the Poetic Edda and the Gylfaginning of the Prose Edda, respectively. Both tales painted Frigg as both a maternal figure and a ruler in her own right.

Frigg in the Grímnismál

Though the Grímnismál, or the “Ballad of Grimnir,” concerned the fate of Grimnir, it also contained a fascinating frame story. Agnar and Geirröth were the young sons of Hrauthung, a mighty king. The boys were on a fishing expedition one day when they were cast out to sea by a sudden storm. When they came ashore, the pair were found by a peasant farmer and his wife. The peasant tended after Geirröth, while his wife fostered Agnar. In time, the peasant sent Geirröth back to his father’s kingdom, where he discovered that his father had died. Seeing that Geirröth had returned, the people proclaimed him to be the new king.

Odin and Frigg, meanwhile, were sitting in Hlithskjolf—Odin’s throne room—from which they could observe all worlds simultaneously. Together, king and queen observed Geirröth and Agnar from afar. The peasant and wife that had fostered the young boys were no ordinary mortals; they were, in fact, Odin and Frigg (Odin, at least, was known for shapeshifting). Odin, then, had fostered Geirröth, while Frigg had fostered Agnar. Naturally, Odin praised Geirröth for his wisdom and power, but slandered Agnar: “Seest thou Agnar, thy fosterling, how he begets children with a giantess in the cave? But Geirröth, my fosterling, is a king, and now rules over his land.”[2]

Not content to watch idly as her fosterling was rebuked, Frigg retorted with a critique of her own. She said of Geirröth, "He is so miserly that he tortures his guests if he thinks that too many of them come to him." Odin disagreed with her, and the two decided to make a wager. Odin would go to Geirröth’s court in disguise, and the gods would discover the truth of the matter. Determined to win, Frigg sent a maiden to Geirröth with a message: a wizard would soon arrive at Geirröth’s court and attempt to “bewitch” the king.

Soon enough, a traveler named Grimnir arrived in Geirröth’s court. The traveler offered his name and nothing more, so Geirröth “had him tortured to make him speak, and set him between two fires, and he sat there eight nights.” Eventually, Geirröth’s younger son brought poor Grimnir a horn of ale. The tale that Grimnir told while sipping this ale formed the core of the Grimnismol, and it was here that the frame story ended.

While Frigg did not again appear in the text, it was clear that she had won the wager. In outsmarting Odin, she proved herself to be a fierce foster mother who was willing to resort to torture in order to defend her fosterling.

Frigg and the Death of Baldur

One of the best known stories in all of Norse mythology, the death of Baldur was a cornerstone of the Gylfaginning, part of the Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson’s thirteenth-century Prose Edda. The story prominently featured Frigg as a grieving mother who would move mountains to resurrect her beloved son.

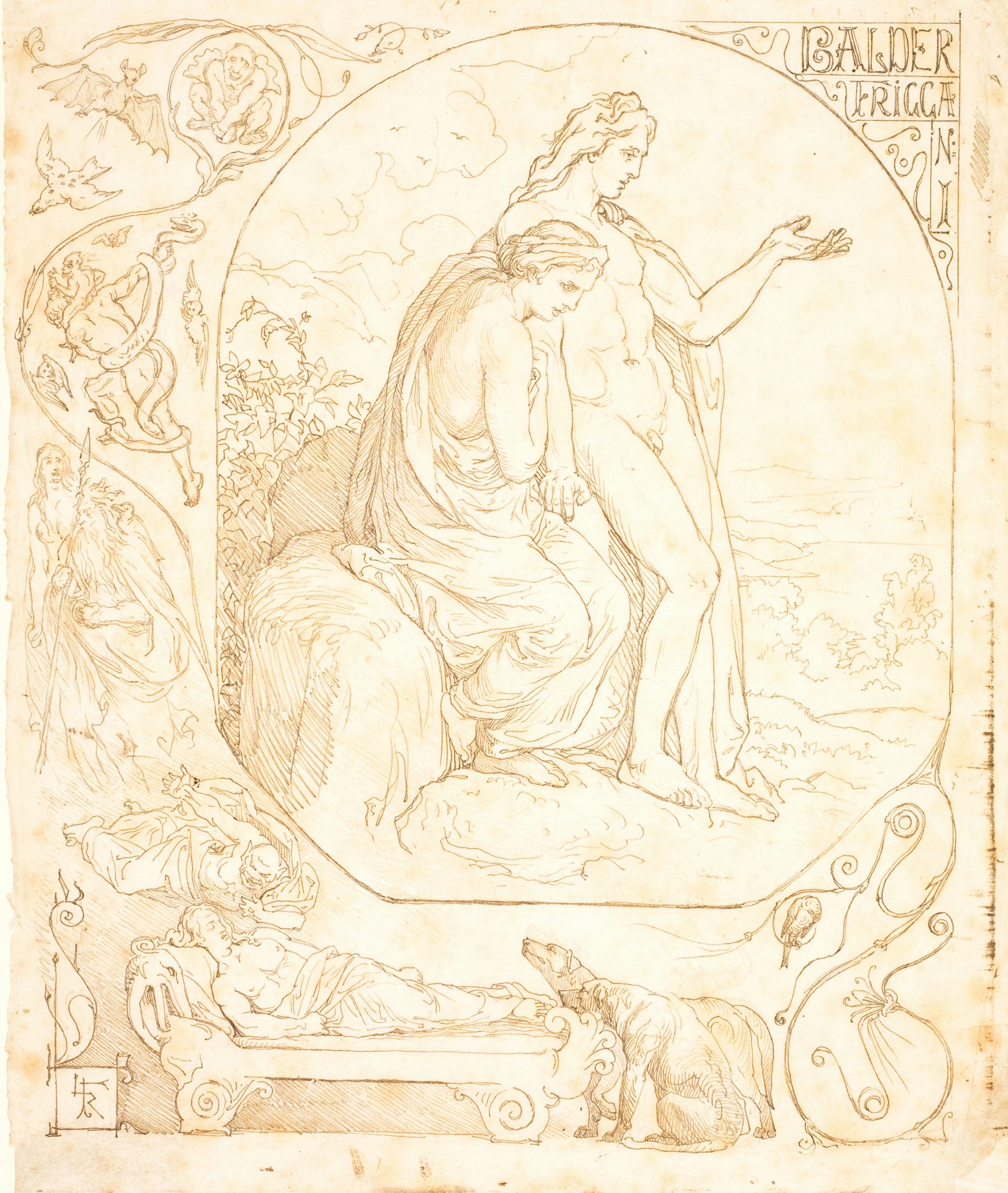

Late 19th century drawing of Frigga and Baldur by Danish artist Lorenz Frolich

National Gallery of DenmarkPublic DomainOne night, Baldur had a nightmare in which he foresaw his own death. When Frigg dreamt the same dream, Odin was compelled to act. Mounting Sleipnir, his eight-legged horse, Odin rode to Hel, the realm of the dead, in search of an oracle that could decipher such portentous dreams.

Odin found the völva and, using a magic of his own, resurrected her from the dead (This völva was likely the same one who narrated the Völuspá).Upset at being so rudely awakened, the völva at first refused to tell Odin anything. When the völva eventually decided to cooperate, what she told Odin confirmed his worst fears: Baldur would indeed die, and those who loved him would mourn.

When Odin returns with the news, Frigg was devastated. Determined to defy the prophecy, she approaches all things in creation, living and inert, and made them promise never to harm her son: “And Frigg took oaths to this purport, that fire and water should spare Baldur, likewise iron and metal of all kinds, stones, earth, trees, sicknesses, beasts, birds, venom, serpents.”[3] Frigg took oaths from everything, save for an innocent shrub of mistletoe.

Unfortunately, wicked Loki, the impish trickster of the Norse pantheon, eventually discovered Frigg’s oversight. Disguising himself in the form of a woman, Loki approached Frigg and asked her whether all things had sworn oaths never to harm Baldur. Not knowing the woman’s true identity, Frigg conceded that she had not demanded the oath from a humble sprig of mistletoe. Upon hearing this news, a gleeful Loki rushed off to locate the mistletoe and fashion a spear from it. When he returned, he found that the gods were hurling missiles at Baldur and making sport of his invulnerability. Scanning the crowd, Loki spied the blind god Hodr (meaning “slayer”). Handing him the spear, Loki told him to throw it directly at Baldur. Hodr did so, and the spear struck true, mortally wounding Baldur.

Nearly overwhelmed by her sorrow, Frigg asks for a volunteer to travel to Hel, the overseer of the realm of the dead, and to beg for the release of Baldur. Hermod (her lesser-known son and Baldur’s brother) volunteered and, riding Sleipnir, traveled to the halls of Hel, where he found Baldur. Hermod asked the goddess of death to release Baldur, claiming that the fallen god was the most beloved being in all creation. Hel agreed to release Baldur, but only on the condition that all things weep for Baldur.

As soon as Hermod had given them the news, the Aesir sent messengers throughout the known world. They approached humans and animals, trees and plants, and even inanimate objects such as rocks and stones; all things wept for Baldur. The gods were close to eliciting tears from every last entity in existence when they found an old giantess named Thökk in a remote cave. This giantess—who was really Loki in disguise—refused to cry for Baldur, and in doing so condemned the fallen god to remain in Hel forever:

‘Thökk will weep waterless tears For Baldr’s bale-fare; Living or dead, I loved not the churl’s son; Let Hel hold to that she hath!’[4]

Pop Culture

Compared to other Norse deities, Frigg has not been prominently featured in popular culture. Instead, she has mainly survived as a figure of worship in the collection of Germanic neopagan beliefs commonly known as Heathenry or Heathenism. Practitioners venerate ancient pre-Christian deities, such as Frigg, and observe pre-Christian beliefs, such as naturism.