Euphemus

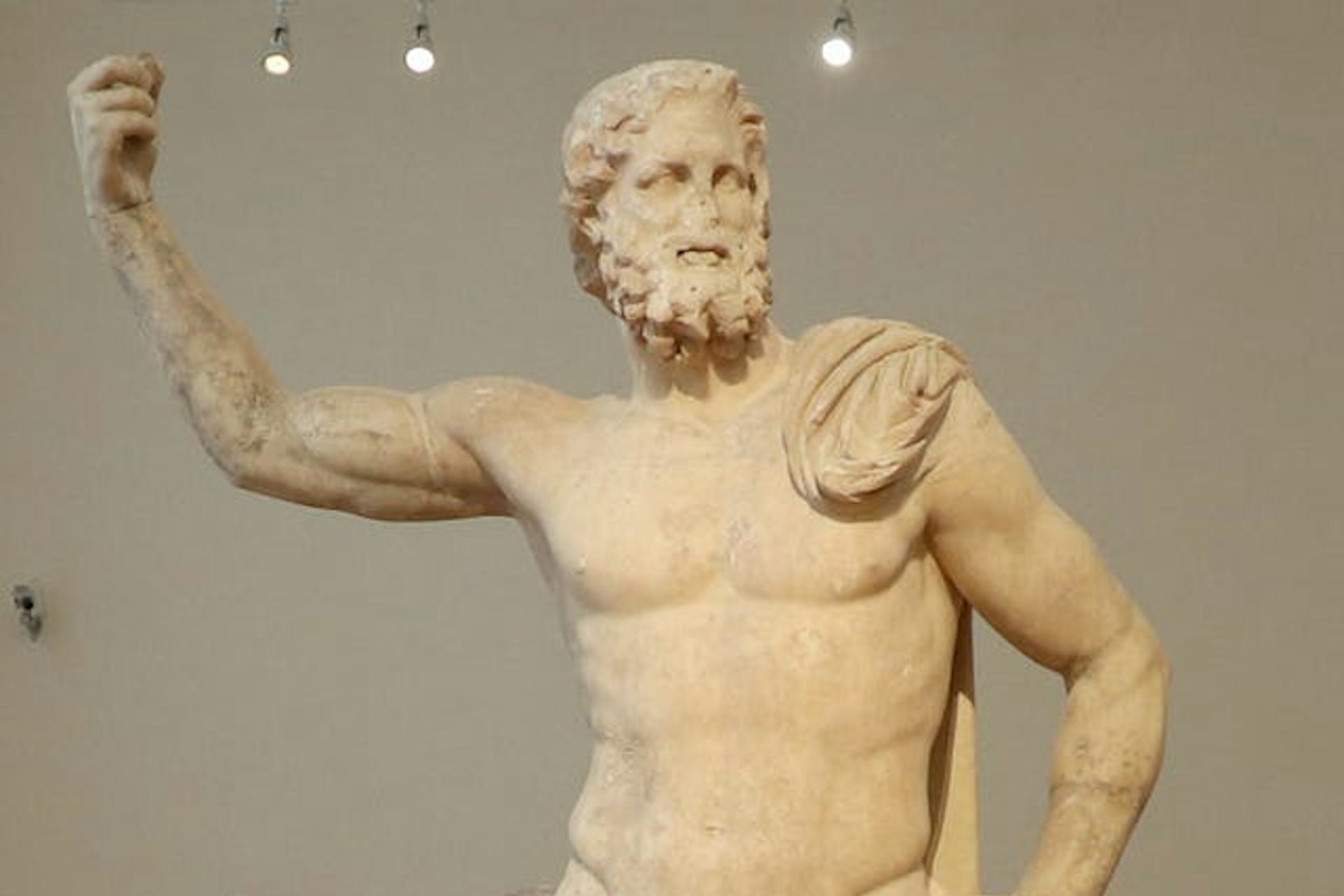

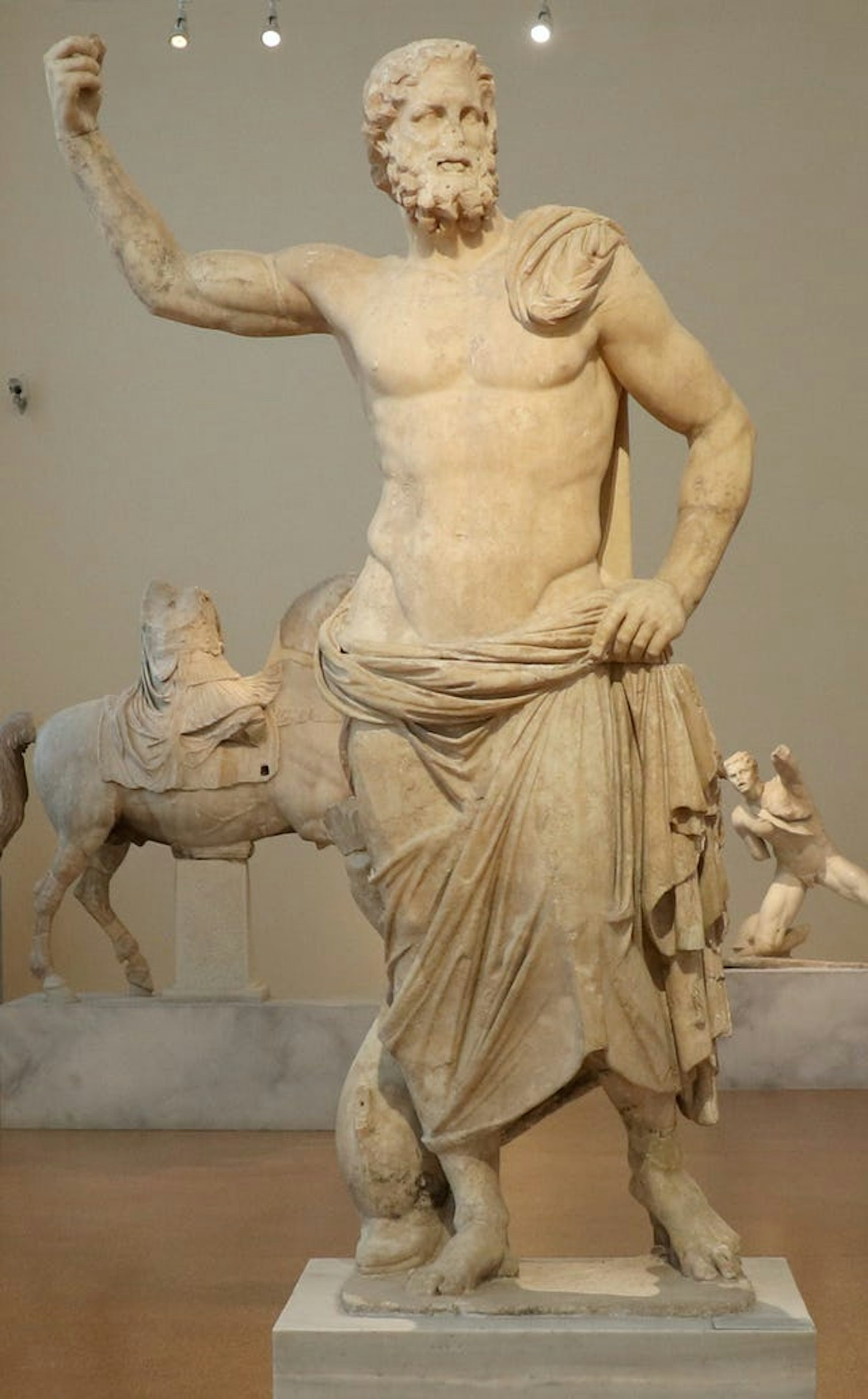

Poseidon of Milos, statue discovered near the Greek island of Milos (125–100 BCE)

National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Athens (cropped and retouched). George E. Koronaios, Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Overview

Euphemus, son of Poseidon and a mortal woman,[1] was a hero connected with the foundation of Cyrene, a Greek city in North Africa. Endowed with the ability to walk on water, Euphemus was an impressive hero who took part in several famous expeditions, including the voyage of the Argonauts and, in some traditions, the Calydonian boar hunt.

While sailing with the Argonauts, he was given a clod of earth, which he was instructed to drop into the sea to ensure his descendants would one day rule over Libya. Euphemus dropped (or lost) the clod near the island of Thera, and it was from there that his descendants eventually colonized Cyrene in Libya, becoming the powerful dynasty of the Battiads.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Euphemus” (Greek Εὔφημος, translit. Eúphēmos) is fairly straightforward. The name is made up of two elements: the Greek prefix εὐ- (eu-), meaning “well, good,” and the verb φημί (phēmí) or φάσκω (pháskō), meaning “to speak, say” (itself a word with Indo-European roots). “Euphemus” can thus be translated as “he who is well-spoken of” or “he who is renowned.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Euphemus Εὔφημος (translit. Eúphēmos) Phonetic

IPA

[yoo-FEE-muhs] /yʊˈˈfi məs/

Attributes

General

As the son of a god and a mortal, Euphemus could be described as a demigod. His most distinguishing characteristic was his ability to walk on water—a power that reflected his descent from Poseidon, the god of the sea.[2]

Iconography

A few artistic representations of Euphemus are known from antiquity. According to Pausanias, Euphemus was shown on the famous Cypselus Chest (ca. 550 BCE) as one of the heroes who took part in the funeral games of Pelias, the king who had sent Jason to fetch the Golden Fleece. It seems that Euphemus was represented as the winner of the chariot race.[3]

A meeting between Euphemus and the god Triton was also illustrated in a bronze statue group—probably a first-century CE Roman copy of a third-century BCE Greek original.[4]

Family

Euphemus’ father was Poseidon, the ruler of the sea and one of the most powerful gods of the Greek pantheon. His mother’s name and identity varied depending on the source: she may have been Mecionice of Hyrie, the daughter of either Eurotas or Orion;[5] Europa, the daughter of Tityus;[6] or Doris/Oris, the daughter of Eurotas.[7]

Poseidon of Milos, statue discovered near the Greek island of Milos (125–100 BCE)

National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Athens (cropped and retouched). George E. Koronaios, Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Euphemus married Laonome, the daughter of Amphitryon and Alcmene and thus the half-sister of the great Heracles.[8] While sailing with the Argonauts, Euphemus also took a lover named Lamache, who gave him a daughter, Leucophanes. This Leucophanes was said to have been the ancestor of Battus, who many generations later founded the Greek colony of Cyrene in North Africa.[9]

Mythology

Euphemus, the Argonauts, and Cyrene

Ancient sources agree that Euphemus was one of the Argonauts—the heroes who sailed with Jason to steal the Golden Fleece.[10] Indeed, Euphemus seems to have been born for the role: the ability to walk on water would certainly have been an asset on a great voyage across the Aegean and Black Seas.

Even so, Euphemus was not the most distinguished or prominent of the Argonauts; he was eclipsed by heroes such as the winged twins Calais and Zetes (the “Boreads”), Castor and Polydeuces (the “Dioscuri”), and, of course, Jason himself. But Euphemus occasionally took a more active role in the voyage.

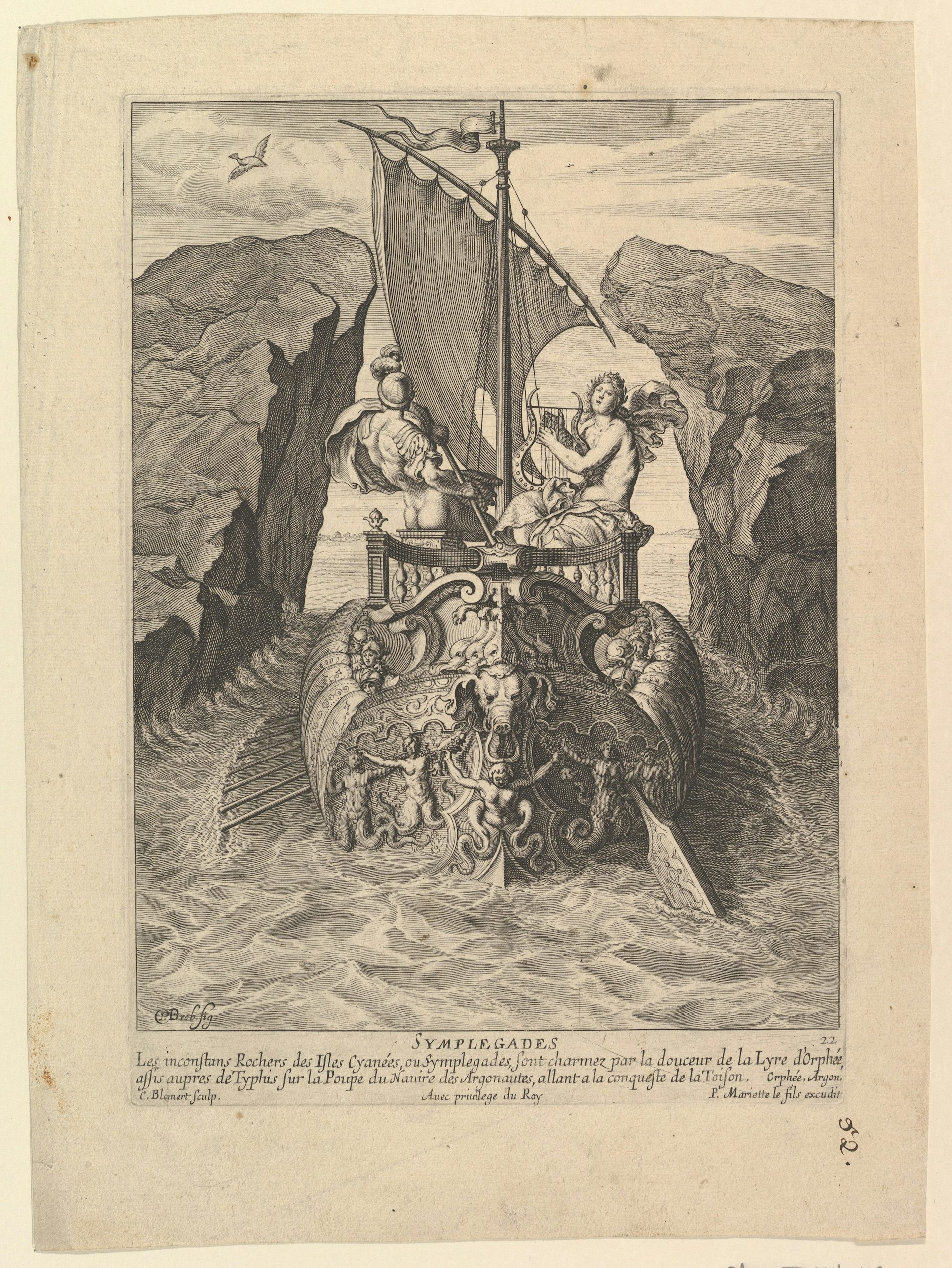

According to Apollonius of Rhodes, Euphemus was the Argonaut entrusted with sending the dove through the Symplegades, or “Clashing Rocks”; when the dove made it through the cliffs (which were constantly slamming into each other), the Argonauts understood it as a sign from the gods that they would make it through as well.[11]

Symplegades by Cornelis Bloemaert (17th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBut the myth of Euphemus really begins on the Argonauts’ return journey. Following a storm, the men were washed ashore on the sands of Libya, in North Africa. After much wandering in the desert, they finally came upon a mysterious deity (called either Eurypylus or Triton, depending on the source).

This deity gave Euphemus a clod of earth and promised him that the fourth generation of his descendants would return to Libya and found an important city there. The god then helped the Argonauts return to sea.

During the voyage home, however, Euphemus dropped the clod of earth near the island of Thera (in one tradition, the island actually arose from the clod). It is unclear whether he did this accidentally or based on advice he had received in a dream. Either way, Euphemus had dropped the clod prematurely; he was supposed to wait until the Argonauts reached Taenarum, on the Laconian coast of the Peloponnese.[12]

Because of this, the witch Medea—who had helped the Argonauts steal the Golden Fleece, and who was accompanying them on their return journey—prophesied that Euphemus’ descendants would not reach Libya until the seventeenth generation now, rather than the fourth.

In spite of this delay, Euphemus still became the ancestor of the Battiads, the family that would someday establish and rule over the Greek colony of Cyrene. The first of the Battiads, Battus, claimed descent from Euphemus and a Lemnian woman (sometimes called Lamache), with whom Euphemus had had a child during the voyage of the Argonauts.

According to myth, Euphemus’ descendants first traveled to Sparta before settling in Thera, where Euphemus had dropped the clod of earth. It was from Thera that Battus—born in the seventeenth generation after Euphemus, as legend had foretold—set out to settle Cyrene in North Africa in 631 BCE.[13]

Other Exploits

The Greeks knew Euphemus chiefly for his role as an Argonaut and as the mythical ancestor of the Battiads. But he was sometimes said to have taken part in other exploits as well.

Euphemus participated in the famous funeral games for Pelias, the villainous king of Iolcus who had sent Jason to fetch the Golden Fleece; it was said that Euphemus won the chariot race during these games.[14] According to the Roman mythographer Hyginus, Euphemus also participated in the Calydonian boar hunt.[15]

Popular Culture

Euphemus features as a minor character in some modern adaptations of the myth of the Argonauts. Instead of being able to walk on water, Euphemus is generally represented—more believably, if somewhat more blandly—as merely a very good swimmer. This is the case in Robert Graves’ novel Hercules, My Shipmate (1943) and in the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts.