Eris

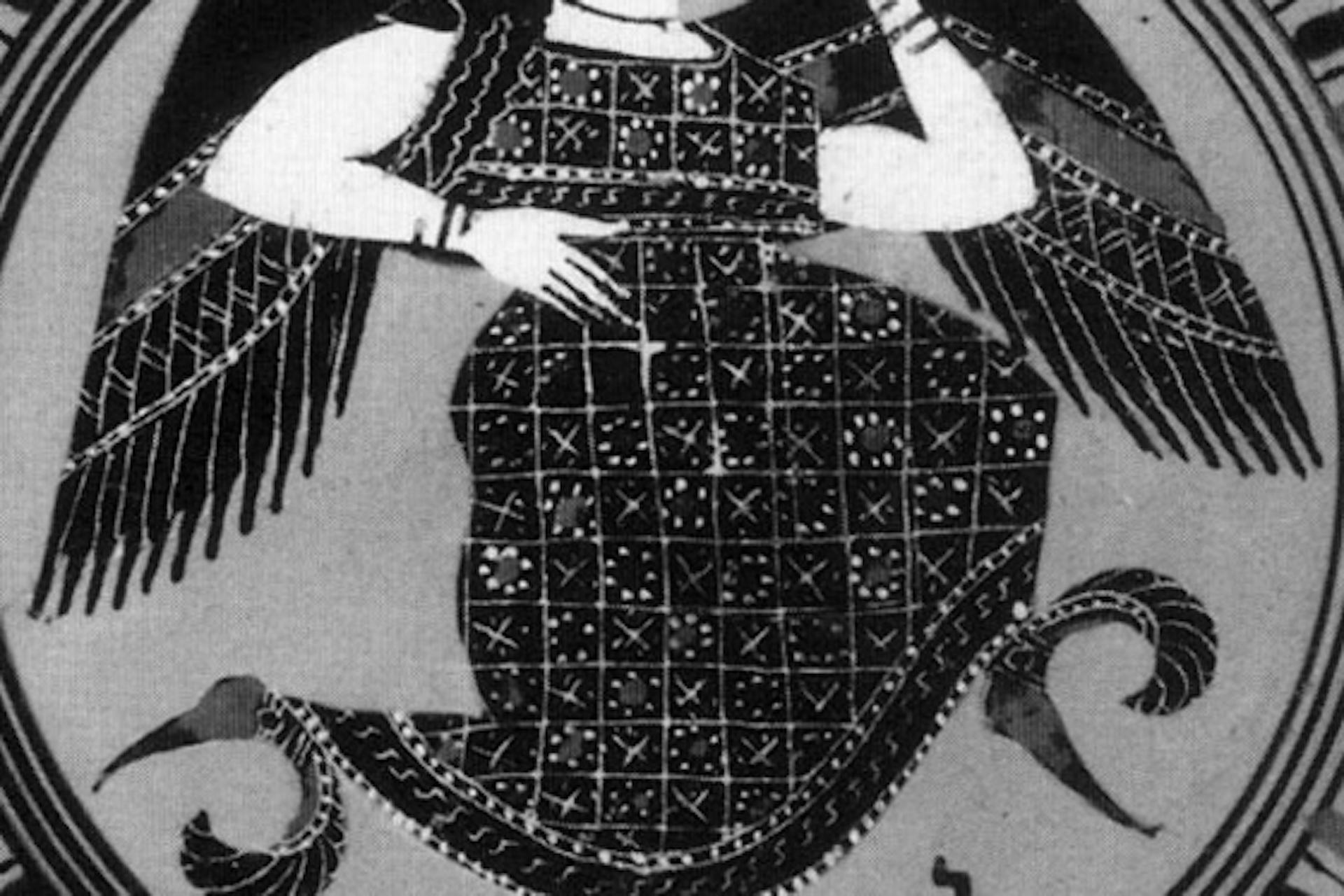

Tondo of an Attic black-figure kylix showing Eris (ca. 575–525 BCE)

Antikensammlung, BerlinPublic DomainIntroduction

Eris was the vicious personification of strife, a goddess who delighted in conflict, rivalry, and bloodshed. She was commonly regarded as a daughter of Nyx, “Night” personified, and was a devoted crony (or even sister) of the war god Ares. Though she had no consort, she gave birth on her own to numerous malicious forces, including Ponos (“Toil”), Lethe (“Forgetfulness”), and Ate (“Delusion”).

Eris did not have many myths of her own, but she was largely responsible for inciting the Trojan War. Angry that she had not been invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, Eris caused Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite to quarrel over a golden apple inscribed with the words “to the fairest.” This quarrel led directly to the Judgment of Paris, which in turn led to the abduction of Helen and the bloody war to get her back.

Etymology

The name “Eris” (Greek Ἔρις, translit. Éris) is identical to the ancient Greek word for “strife” or “discord.” However, the etymology of this word is unknown. It may be related to the Greek words ὀρίνω (orínō), “to stir up, excite”; ἐρέθω (erethō), “to anger, provoke”; or even Ἐρινύς (Erinýs), “Fury, spirit of vengeance.” But the name may also have more remote, pre-Greek origins.[1]

The Roman counterpart of the Greek Eris was Discordia (from which the English word “discord” is derived).

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Eris Ἔρις (Éris) Phonetic

IPA

[ER-is] /ˈɛr ɪs/

Attributes

Functions and Characteristics

The goddess Eris represented strife in all its forms. Hesiod described her as a cruel, “hard-hearted”[2] figure who inspired and reveled in every kind of conflict. It is hardly surprising, then, that Eris was closely associated with destructive war gods such as Ares and Enyo; indeed, she was never far away when a battle was being fought. Homer portrayed Eris as a goddess

that rageth incessantly, sister and comrade of man-slaying Ares; she at the first rears her crest but little, yet thereafter planteth her head in heaven, while her feet tread on earth.[3]

Later, though, Hesiod distinguished between two Erises: one was a purely negative force, the personification of destructive strife, while the other was a more positive force who fostered productive competition.[4]

Eris was typically imagined as having a hideous and horrifying appearance. Virgil pictured her as a creature of the Underworld, with snakes for hair and a bloody headband.[5] Statius portrayed her standing guard at the home of Mars (the Roman Ares).[6]

Iconography

Eris seems to have been present in ancient art from a very early period. The first Greek epics often referred to visual representations of Eris, usually on decorative armor worn by heroes.[7] She is known to have appeared as an ugly, savage figure on the Cypselus Chest, an important Greek artifact known today only from ancient descriptions.[8]

While Eris was typically shown as ugly, some artists gave her an ordinary or even attractive appearance. She often sported wings and/or winged sandals. Eris was a popular figure in vase paintings, especially those depicting the Judgment of Paris.[9]

Family

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Eris was one of the children born from Nyx, the primordial goddess of night; she had no father. Her siblings included other menacing forces like Thanatos (“Death”), Hypnos (“Sleep”), Nemesis (“Retribution”), and the Moirae (“Fates”).[10]

The Roman mythographer Hyginus, however, made Nemesis the daughter of Nyx and her consort Erebus, the deity who embodied the darkness of the Underworld.[11] In yet another genealogy, Homer called Eris the sister of Ares, hinting at a tradition in which she was a child of Zeus and Hera (like Ares).[12]

Eris gave birth (without a partner) to further personified forces—beings no less terrible than she. Among these children were Ponos (“Toil”), Lethe (“Forgetfulness”), Limos (“Hunger”), Algae (“Pains”), Hysminae (“Combats”), Machae (“Battles”), Phonoi (“Murders”), Androctasiae (“Manslaughters”), Neikea (“Quarrels”), Pseudologoi (“Lies”), Amphillogiae (“Altercations”), Dysnomia (“Lawlessness”), Horkos (“Oath”), and Ate (“Delusion”).[13]

Eris also had two nephews: Phobos (“Fear”) and Deimos (“Panic”).[14]

Mythology

The Golden Apple: Eris and the Trojan War

Though Eris had a limited mythology, she did play a central role in one popular myth: that of the golden apple and the Judgment of Paris. In this tradition, it was Eris who set in motion the events that led to the Trojan War.

It all began when the mortal hero Peleus married the goddess Thetis. The wedding was a lavish affair, attended by all the gods. But Eris, as the dreaded goddess of strife, was not invited.

Furious at being insulted in this way, Eris showed up at the wedding anyway and threw a golden apple into the midst of the divine guests, inscribed with the words “to the fairest” (in some accounts, this was one of the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides). The three most powerful goddesses—Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite—immediately started arguing over which of them deserved to be crowned the “fairest.”

The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis by Jacob Jordaens after Peter Paul Rubens (between 1633 and 1638)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainEventually, the handsome Trojan prince Paris was tasked with deciding the matter. Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite all presented themselves to the prince. But not wanting to rely on their looks alone, each goddess tried to bribe Paris.

Hera promised him wealth and power; Athena promised him military glory; and Aphrodite promised him the love of Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris (rather short-sightedly) preferred Aphrodite’s bribe and thus gave her the apple.

Aphrodite made good on her promise, with far-reaching consequences. She helped Paris seduce and steal Helen away from her husband Menelaus, the king of Sparta. Menelaus promptly amassed a large army to sail to Troy and get Helen back. This marked the beginning of the Trojan War.[15]

Not content with simply provoking the Trojan War, Eris continually embroiled herself in the decade-long conflict. In Homer’s Iliad, Eris is shown rousing the Greeks and Trojans to battle on multiple occasions. In one scene, she sweeps into the Greek camp carrying “a portent of war” and unleashes a great shout to inspire violence in the warriors.[16]

Polytechnus and Aedon: Eris and Marital Strife

In another myth, Eris demonstrated her ability to cause discord in a more domestic context. This story told of a happy couple, the carpenter Polytechnus and his wife Aedon, who thoughtlessly boasted that they loved each other even more than Zeus and Hera. This frivolous comment angered Hera, who sent Eris to punish them.[17]

Eagerly following Hera’s orders, Eris breathed the spirit of competition into Polytechnus and Aedon. Polytechnus was building a standing board for a chariot, while Aedon was weaving a tapestry, and the couple decided to make a bet as to who would complete their task first; the loser, they decided, would bring the winner a female servant.

Aedon ended up finishing her tapestry first and thus won the competition. Polytechnus was filled with resentment and resolved that he would have the last laugh.

He went to the home of Aedon’s father Pandareus and asked to bring Aedon’s sister Chelidon home for a visit. He then raped her, cut her hair short, and presented her to Aedon as the “servant” she had won, threatening to kill Chelidon if she revealed the truth to her sister.

Aedon, not recognizing her sister, treated her new servant very cruelly. But one day Aedon overheard Chelidon lamenting her situation and thus discovered the truth. Together, Aedon and Chelidon plotted a gruesome revenge against Polytechnus: they killed Itys (Polytechnus and Aedon’s only son), cooked him, and fed him to Polytechnus.

When Polytechnus discovered what had happened, he pursued Aedon and Chelidon to the home of their father Pandareus. But Pandareus caught Polytechnus, tied him up, smeared him with honey, and threw him into his sheepfold as insect fodder.

At this point, Aedon took pity on her husband and tried to help him. This infuriated her father and brother, who attacked her and were on the verge of killing her. Zeus, to prevent things from getting even worse, finally turned them all into birds: Pandareus became a sea eagle, Aedon’s mother a kingfisher, Polytechnus a woodpecker, Aedon’s brother a hoopoe, Chelidon a swallow, and Aedon a nightingale.[18]

Popular Culture

Eris is still remembered today as the divine embodiment of discord and strife. In the 1960s, she was adopted as the principal deity of Discordianism, a religion (or parody religion) that believes order and disorder are illusory byproducts of the human nervous system. The overseers of the religion claim to speak with Eris using their pineal glands.

Eris has also appeared in some contemporary adaptations of ancient mythology. For example, she is the chief antagonist of the animated film Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas (2003), where she is voiced by Michelle Pfeiffer.