Eos

Overview

Eos, daughter of the Titans Hyperion and Theia, was the goddess of the dawn. Each day, she rose from the Ocean and rode her chariot across the sky, dispersing the shadows of the night. This cleared the way for her brother Helios, the god of the sun, who followed her in his blinding chariot. When Eos and Helios had both completed their journeys across the sky, it was time for their sister Selene to shine as the moon.

Eos had an affinity for attractive young men. Her marriage to the Titan Astraeus did not stop her from taking several lovers, including the hunters Cephalus and Orion. But her most famous consort was Tithonus, a handsome Trojan prince. In one popular myth, Eos managed to make Tithonus immortal—but not ageless. This meant that even as Eos remained eternally beautiful and youthful, Tithonus slowly wasted away until he was nothing but a shrunken, shriveled shell.

Etymology

The name “Eos” (Greek Ἠώς, translit. Ēṓs) was also the ancient Greek word meaning “dawn” and dates back to the Mycenaean period (ca. 1600–1100 BCE). In the Linear B writing system of that era, used before the development of the Greek alphabet, her name was rendered as a-wo-i-jo.

Etymologically, the Greek Eos (as a proper name or a noun) seems to be derived from the Indo-European root *h₂eus-ōs (“dawn”). Similar words for dawn (or dawn goddesses) can be found in other Indo-European languages—for example, the Latin aurora.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Eos Ἠώς (translit. Ēṓs) Phonetic

IPA

[EE-os] /ˈi ɒs/

Alternate Names

Eos’ name varied slightly across local dialects. Alternate spellings included the Attic Ἠεώς (Heṓs), the Aeolic Αὐώς (Auṓs), and the Doric Ἀώς (Aṓs).

Eos was sometimes identified with Hemera, the goddess of the day, though they were usually regarded as separate goddesses. Eos’ Roman counterpart was called Aurora.

Titles and Epithets

Eos had many important epithets, including ῥοδοδάκτυλος (rhododáktylos, “rosy-fingered”), ῥοδοπάχυς (rhodopáchys, “rosy-armed”), χρυσοπάχυς (chrysopáchys, “golden-armed”), κροκόπεπλος (krokópeplos, “saffron-robed), and ἠριγένεια (ērigéneia, “early-born”).

Attributes

Eos personified the arrival of dawn. She was usually imagined as a beautiful goddess who reflected the pale colors of the dawn sky, as revealed by such epithets as “rosy-fingered” and “saffron-robed.”

Eos’ chariot was pulled by two immortal horses, called Lampus (“Shiner”) and Phaethon (“Blazer).”[2] Every morning, she rode her chariot from her home on the edge of the Ocean across the sky, dispelling the night and bringing the new day. She was often accompanied by her son Eosphorus (the morning star) or by the Horae, daughters of Zeus associated with time and the seasons.

In art, Eos was usually represented as a winged goddess; she was sometimes shown driving her chariot. Various scenes from her mythology—including her grief over the death of her son Memnon as well as her pursuit of Cephalus and Tithonus—can be found in ancient art, especially in vase paintings.[3]

Terracotta lekanis showing Eos in her chariot soaring above Eros, a woman, and a swan. Attributed to the Stuttgart Group (late 4th century BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of Fine ArtPublic DomainFamily

In the standard tradition, Eos was the daughter of the Titans Hyperion and Theia and the sister of Helios and Selene.[4] But other sources called her mother Euryphaessa,[5] Aethra,[6] or Basileia[7] (possibly alternate names for Theia), or even Nyx[8] (the personification of night). Others called her father Pallas[9] or Helios.[10]

Eos married the Titan Astraeus, son of Crius and Eurybia, and together they had several children: the Anemoi (“Winds”), named Zephyrus (the west wind), Boreas (the north wind), and Notus (the south wind), as well as Eosphorus (the morning star) and the Astra (“Stars”).[11] Some said that Eos and Astraea were also the parents of Eurus (the east wind)[12] and Astraea, a virgin goddess of justice and innocence.[13]

Family Tree

Mythology

Dawn’s Lovers

Aphrodite’s Curse

Eos’ mythology was dominated by her pursuit of dashing lovers, particularly young, mortal men. According to Apollodorus, this all started when Eos slept with the war god Ares. Aphrodite, the goddess of love—and, more importantly, Ares’ lover—did not appreciate this. To punish Eos, she cursed her to always be in love.[19]

Cephalus

There are a few different versions of the myth of Eos and the handsome Athenian Cephalus. According to the common tradition, Cephalus initially resisted Eos’ advances; he was married to (or about to marry) a woman named Procris. To overcome this reluctance, some sources claimed that Eos simply abducted Cephalus and had her way with him. But other sources said that Eos wanted Procris out of the picture and so tricked her into “cheating” on Cephalus.

Aurora and Cephalus by François Boucher (1733). Museum of Fine Arts, Nancy, France.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn one version, Eos prompted Cephalus to test Procris by approaching her disguised as a stranger. That way, he could try to seduce her and see if she would remain faithful. When Procris failed the test, Cephalus was devastated and Procris fled in shame, leaving Cephalus to seek comfort in Eos’ embrace.

In another version, Eos actually changed Cephalus’ appearance herself and gave him gifts to pass on to Procris. Cephalus brought the gifts to Procris and slept with her, after which Eos restored his true appearance (it is not clear if Cephalus knew that his appearance had been changed). Procris, realizing that she had been tricked, fled, leaving Cephalus to Eos.

In other versions of the myth, Eos had nothing to do with Cephalus’ “test” of his wife’s fidelity, and in some accounts, Procris actually did sleep with another man (rather than just Cephalus in disguise). Either way, the tale ended tragically, with Cephalus and Procris eventually reconciling, only for Cephalus to accidentally kill Procris in a hunting accident.[20]

Orion

Another ancient myth tells of how Eos fell in love with the hunter Orion and carried him off to the island of Delos. But for reasons that are unclear, the goddess Artemis became jealous and killed Orion with her arrows.[21]

Tithonus

In another tradition, Eos fell in love with Tithonus, a handsome Trojan prince. This was (and still is) the most famous of Eos’ affairs. Either because she was particularly captivated by this new lover or because she had learned her lesson from the tragic ends of Orion and Cephalus, Eos sought to make Tithonus immortal. She begged Zeus for this rare boon, and her request was granted (in some versions, it was Tithonus himself who made the request).

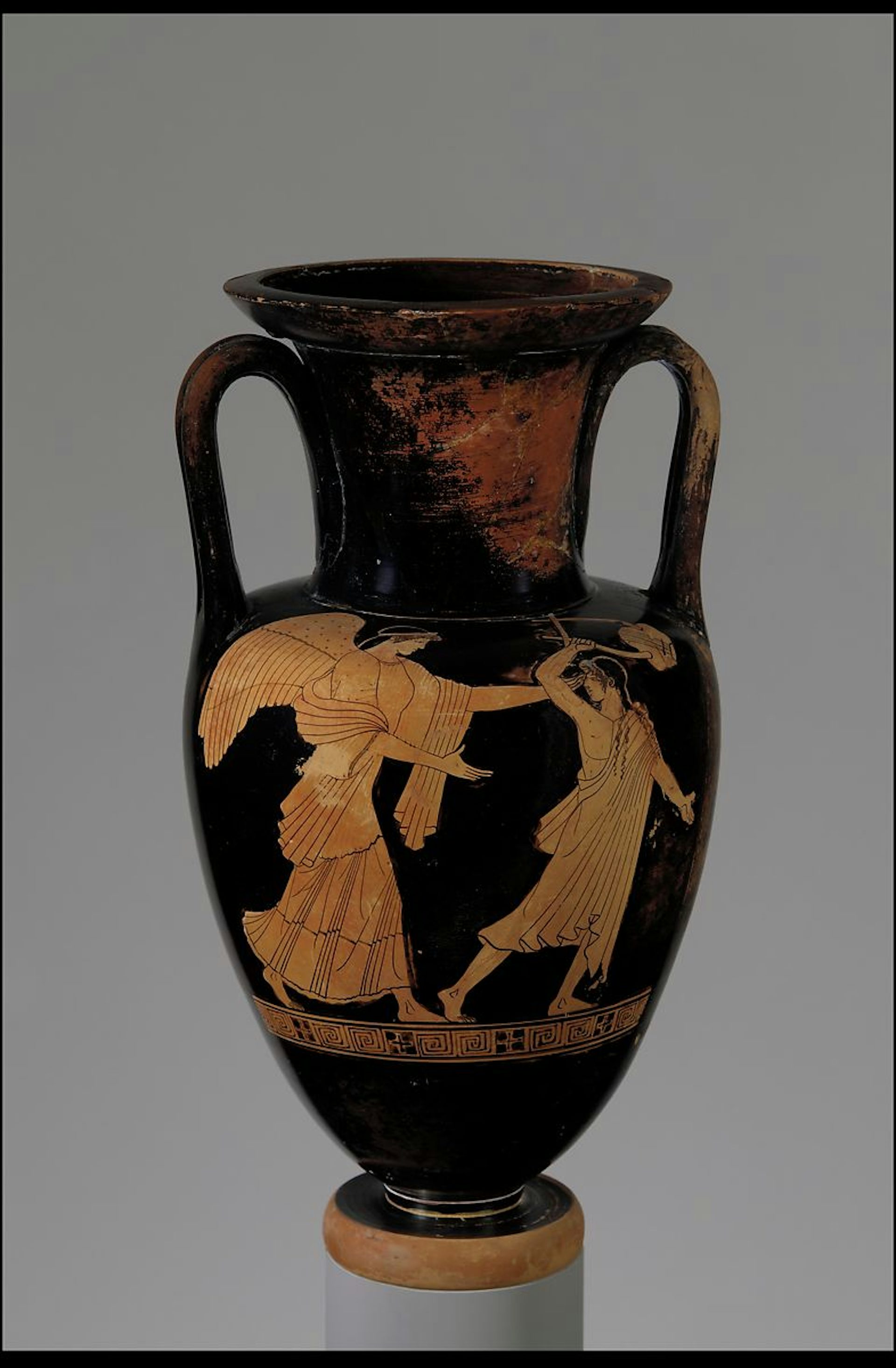

Terracotta red-figure Nolan-neck amphora showing Eos pursuing Tithonus. Attributed to the Achilles Painter (ca. 470–460 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBut Eos forgot to ask that Tithonus be made ageless as well as immortal. Thus, even though he would live forever, he continued to age. Eventually, he withered away to almost nothing as “loathsome old age pressed full upon him, and he could not move nor lift his limbs.”[22] Eos could do nothing but lock the eternally fading Tithonus in a room and forget about him. According to some authors, the tiny, shrill Tithonus was finally transformed into the cicada, regarded by the ancient Greeks as the most musical of all insects.[23]

Cleitus

We know much less about the myth of Eos and Cleitus. According to Homer, Eos carried off the handsome Cleitus, the son of a seer named Mantius, to live with her among the “deathless ones.”[24] This suggests that Eos made Cleitus immortal (though hopefully with better results than with Tithonus).

Dawn’s Children

Eos had both immortal and mortal offspring. Her immortal children, such as the four winds and the countless stars, were largely associated with the celestial or astral realms. But Eos’ mortal children tended to meet sad ends. For example, Emathion, one of the sons of Eos and Tithonus, was killed by Heracles,[25] while Phaethon, sometimes called the son of Eos and Cephalus (see above), died while attempting to drive the chariot of the sun.

Eos had a more prominent role in the myth of her son Memnon. The product of Eos’ relationship with Tithonus, Memnon was an African king, a great warrior, and an ally of Troy during the Trojan War. During the course of the war, he came face to face with Achilles, the mightiest of the Greek warriors at Troy.

Achilles, like Memnon, had a goddess for a mother—Thetis, one of the Nereids. As Achilles and Memnon fought, Thetis and Eos both entreated Zeus on behalf of their respective sons. Zeus weighed the warriors’ fates on his great cosmic scales and determined that it was Memnon’s time to die (though Achilles would fall soon after).

Eos mourned her son’s death terribly. In some traditions, she caused night to fall early so that she could steal Memnon’s body from the battlefield; in others, she made him immortal; in still others, Memnon’s men gave the hero a lavish funeral and were transformed into birds.[26]

Interior of Attic red-figure cup showing Eos with the body of her dead son Memnon. Signed by Douris and Calliades (ca. 490–480 BCE). From Capua, Italy. Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Bibi Saint-PaulPublic DomainWorship

Eos was rarely worshipped in antiquity. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, she describes herself as inferior to all the other gods, bemoaning the fact that, “through all the world / my temples are so few.”[27]

Though Eos may have had a handful of temples or altars in ancient Greece or Rome, no knowledge of them remains. The only evidence we have for an ancient cult of Eos is a single reference to libations that she received in Athens.[28]