Cyclops (Play)

Ulysses in the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus by Constantin Hansen (ca. 1835).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOverview

The Cyclops, produced by Euripides around 408 BCE (or possibly earlier), is the only surviving example of an ancient Greek satyr play. The play presents a burlesque retelling of the myth of Odysseus and the Cyclops Polyphemus, adapted from Book 9 of Homer’s Odyssey.

The Cyclops delves into themes of deception and language, man’s relationship with the gods, and Athenian identity and values. As the only extant satyr play, the Cyclops has been much studied by classical scholars.

Key Facts

Who wrote the Cyclops?

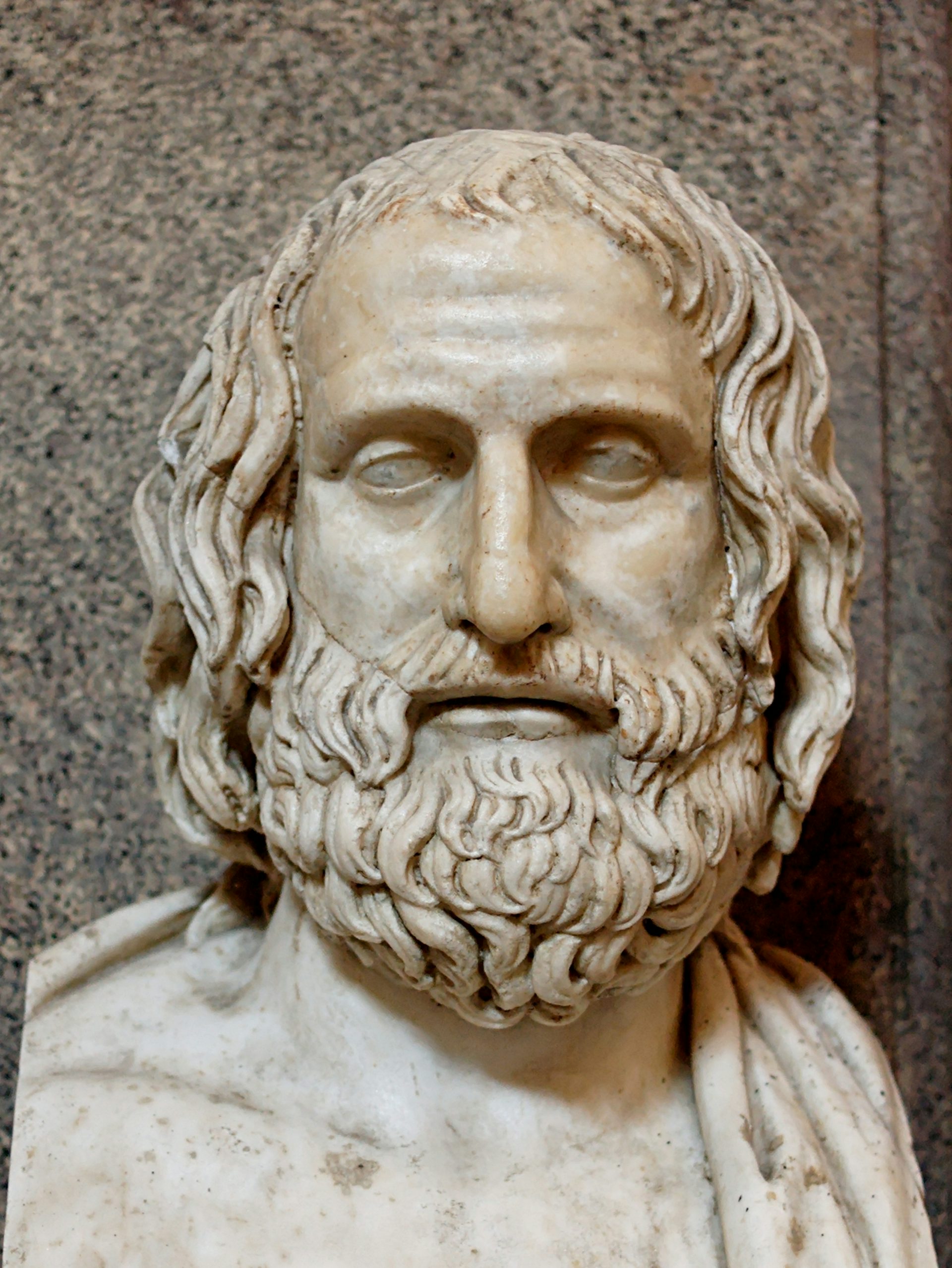

The Cyclops was composed by Euripides, one of the three canonical Attic tragedians (alongside Aeschylus and Sophocles). It is the only satyr play that has survived intact from antiquity; all other satyr plays have been lost or have survived merely as fragments.

Roman bust of Euripides after a Greek original from ca. 330 BCE

Vatican Museums, Vatican / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainWhen was the Cyclops composed?

Today most scholars believe that the Cyclops was written around 408 BCE. But this date is a matter of debate, with some scholars arguing that the play was performed in 424 BCE (together with Euripides’ tragedy Hecuba), or even earlier.

The Theater of Dionysus on the southern slope of the Acropolis in Athens

dronepicrCC BY 2.0What is the Cyclops about?

The Cyclops is a burlesque adaptation of the myth of Odysseus and the Cyclops Polyphemus, best known from Book 9 of Homer’s Odyssey. In the play, Odysseus must escape the clutches of Polyphemus, who has imprisoned the hero and his men and begins devouring them.

Odysseus seeks to enlist the help of the satyrs, who form the chorus of the play (as they did in all satyr plays), though the cowardly satyrs ultimately prove to be of little help.

Odysseus and his Men Slip Away Concealed under Rams by Jacob Jordaens (between 1630 and 1635)

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, MoscowPublic DomainTitle

Euripides’ Cyclops (Greek Κύκλωψ, translit. Kýklōps) is named after the Cyclops Polyphemus, who takes Odysseus and his men captive in the play.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Cyclopes Κύκλωψ, Κύκλωπες Phonetic

IPA

[SY-klops, sy-KLOH-peez] /ˈsaɪ klɒps, saɪˈkloʊ piːz/

Author

Euripides, the author of the Cyclops, was an Athenian tragedian who is usually said to have lived from around 480 BCE to 406 BCE. He was the youngest of the three canonical Athenian tragedians (the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles) and was known for exploring avant-garde, subversive, and innovative themes.

Over the course of his career, Euripides composed some ninety plays, eighteen of which survive in full.[1] Despite his formidable output—we have more plays by Euripides than by Aeschylus and Sophocles combined—he won only four victories at the annual Dionysia competition during his lifetime (with a fifth awarded the year after his death).[2] Yet Euripides’ popularity and literary influence have continued to grow, and some now regard him as the greatest of the Athenian tragedians.

Little is known about Euripides’ personal life; most ancient testimonia and biographies read more like fable than fact. Euripides seems to have been born on Salamis, an island near Athens, to a family of hereditary priests. He was married twice, both times unhappily, and had three sons.

Ancient sources claimed that Euripides was a recluse and may have even lived alone in a cave in Salamis, though the veracity of such stories is obviously dubious. He died in 406 BCE at the court of the Macedonian king Archelaus.

The "Cave of Euripides" on Salamis, where legend said Euripides wrote his plays in isolation

SchuppiCC BY-SA 4.0Throughout his lifetime—and after his death, too—Euripides had a reputation as a challenging and controversial playwright. The comedian Aristophanes, one of his contemporaries, often mocked Euripides as an impious snob. In time, however, Euripides came to be recognized for his capable exploration of emotional realism, his innovative treatment of traditional mythology, and his persistent questioning of contemporary values.

Mythological Context

Euripides’ Cyclops is an adaptation of the myth of Odysseus’ encounter with the Cyclops, best known from Book 9 of Homer’s Odyssey. But the myth might have been familiar to Euripides and his audience from other literary and artistic sources, too, including a play by Aristias titled Cyclops,[3] Cratinus’ comedy Odysseus,[4] and various vase paintings.

In the Odyssey (the most familiar source for the myth), the hero Odysseus lands on the island of the Cyclopes while sailing home from Troy. He and a few of his men are captured by the Cyclops Polyphemus and imprisoned in his cave home, whose entrance is blocked by an enormous boulder that only Polyphemus can move.

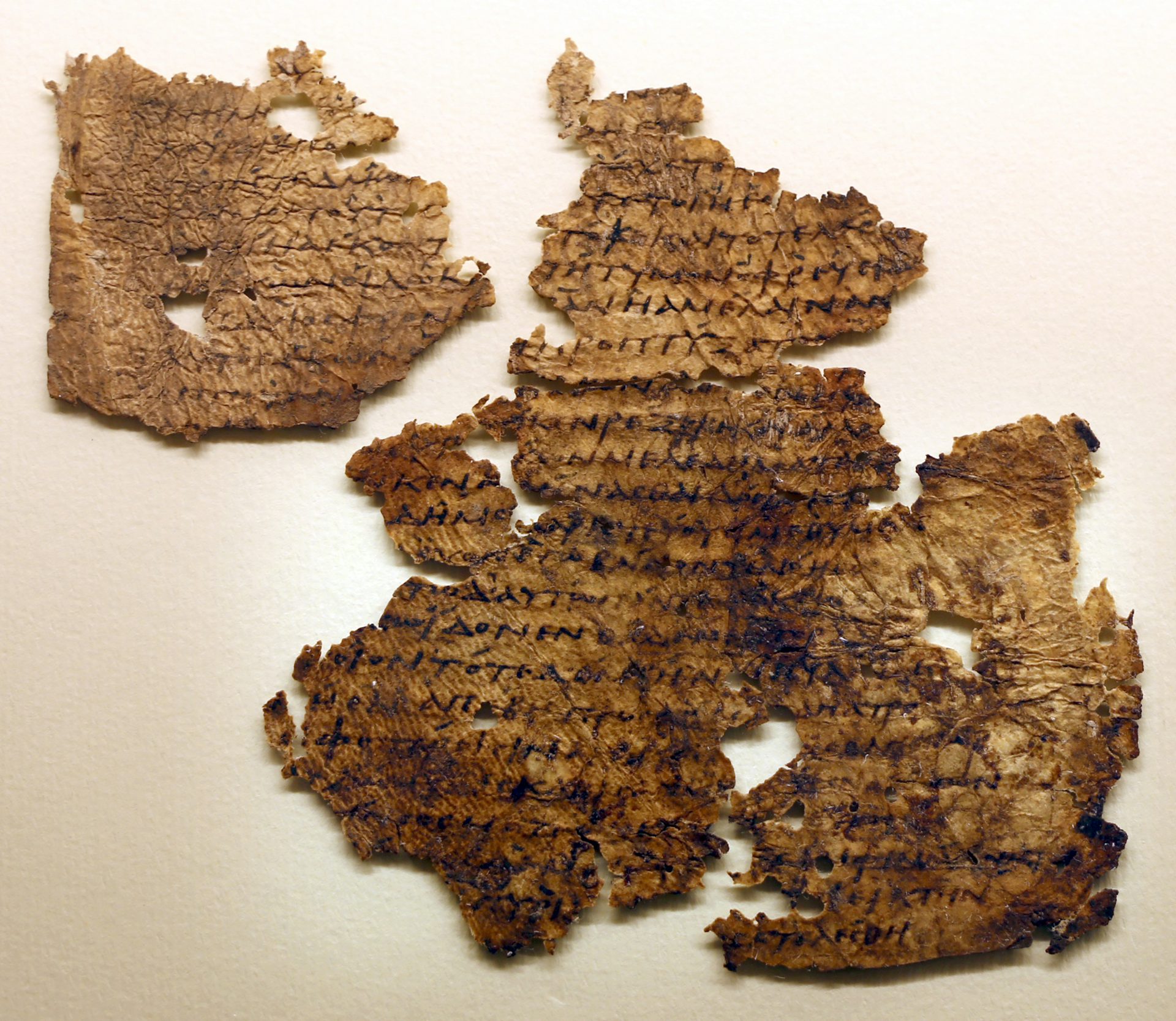

Papyrus fragment of Homer's Odyssey (4.639–63) from the 3rd or 4th century CE

SailkoCC BY-SA 4.0Polyphemus begins devouring Odysseus’ men two at a time, but the crafty hero soon thinks up a plan to escape. He gives Polyphemus some wine, causing him to become drunk. Once Polyphemus is asleep, Odysseus and his men drive a huge stake that they have sharpened into the Cyclops’ eye, thus blinding him.

The next day, when Polyphemus rolls the boulder from the cave’s entrance to pasture his livestock, Odysseus and his men are able to slip out unseen.[5]

There are some key differences, however, between Homer’s narrative and Euripides’ “satyrical” retelling of the myth. The most obvious difference is the presence of the satyrs in Euripides’ play (a requirement for all satyr plays). The fun-loving and childlike satyrs provide comic relief, alternately helping and impeding Odysseus.

But there are other differences, too. For example, the boulder covering the cave entrance is absent in Euripides’ play; in this version, Odysseus blinds the Cyclops not to escape (he can do that easily enough without resorting to violence) but to avenge his murdered men.

Some of the more memorable features of Homer’s narrative are lost as well. In the Odyssey, Odysseus cleverly tells Polyphemus that his name is “Nobody.” That way, when the wounded Cyclops calls out to his brethren after Odysseus has blinded him, all he can tell them is that “nobody” is hurting him, leading the other Cyclopes to assume that he is simply having a bad dream.

Though Euripides’ play mirrors the Odyssey in having Odysseus tell the Cyclops that his name is “Nobody,” the subsequent scene with the other Cyclopes is omitted (instead, Polyphemus complains about “nobody” to the satyrs, who are on Odysseus’ side and would not have helped the Cyclops in any case).

Sculpture of a drunken Dionysus and a satyr, 2nd century CE Roman copy after a Hellenistic Greek original

Palazza Altemps, Rome / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainIn the Odyssey, the blinded Polyphemus tries to prevent Odysseus and his men from leaving the cave by standing in front of the entrance and feeling with his hands to make sure that only his sheep are exiting. Odysseus, however, ties his men to the bellies of the sheep, where Polyphemus is unable to feel them. This scene is also omitted from Euripides’ play, probably because it would have been difficult (if not impossible) to stage.

Characters

The following is a list of speaking characters in Euripides’ Cyclops, in order of appearance:

Silenus (eldest of the satyrs)

Chorus (satyrs)

Odysseus (Greek hero and king of Ithaca)

Polyphemus (a Cyclops and son of Poseidon)

According to the conventions of ancient drama, there were typically only three speaking actors in any given play, which required them to double up on parts if there were more than three roles. However, since the Cyclops only has three speaking parts, the play did not need to employ role doubling; every part would have simply been played by a different actor.

Synopsis

The play is set in front of the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus, near Mount Aetna in Sicily. In the prologue, the satyr Silenus describes his faithful service to Dionysus, the god of wine. He explains that he and the other satyrs were shipwrecked on Sicily while trying to find their divine master, who had been kidnapped by Etruscan pirates.

The satyrs were then captured by the Cyclops Polyphemus, who put them to work as shepherds and tasked Silenus with taking care of his home.

The satyr Chorus enters to sing the parodos (the first choral song). They complain of the drudgery of their labor for the Cyclops and express longing for their former life with Dionysus.

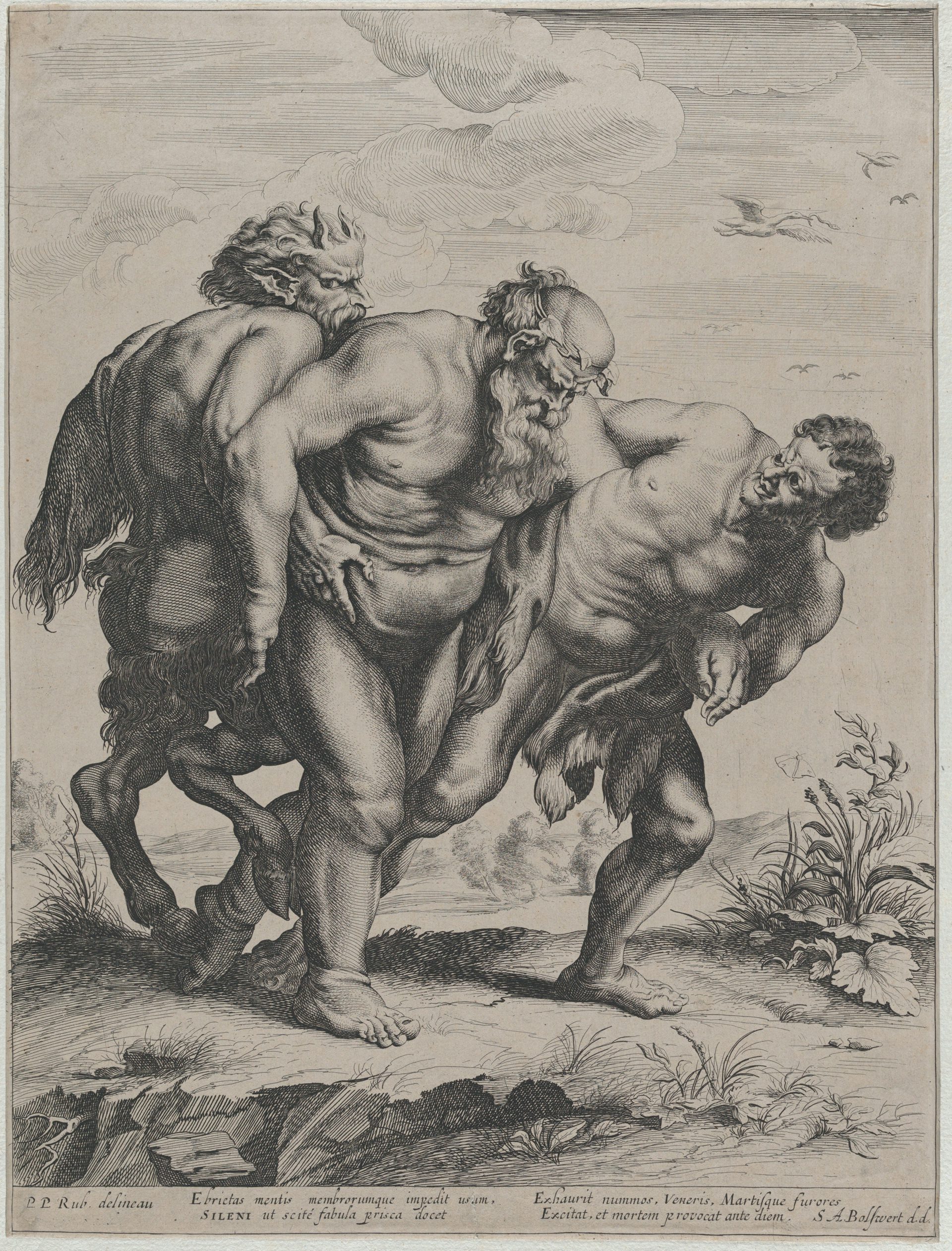

The Drunken Silenus, Supported by a Satyr and a Faun by Schelte Adams à Bolswert after Peter Paul Rubens (1625–1659)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainSilenus spies some men disembarking on the island. He questions their leader, who is Odysseus, one of the heroes who fought at Troy. Odysseus agrees to trade some of his wine for sheep and cheese, but as the deal is being made, the Cyclops returns. Silenus takes Odysseus and his men to the cave.

The Cyclops enters and asks the satyrs what is going on. He spots Silenus, who betrays Odysseus, telling his master that Odysseus and his men have come to rob and kidnap the Cyclops. Odysseus protests that Silenus is lying, but the Cyclops does not believe him. Ignoring Odysseus’ appeals, the Cyclops drags him and his men into the cave.

The satyrs, left outside, sing of the horrors of the man-eating Cyclops. Soon Odysseus emerges and tells of how the monster killed, cooked, and devoured two of his men. He reveals to the satyrs that he has come up with a plan to get the Cyclops drunk and then blind him with a sharpened stake as soon as he has fallen asleep. The satyrs promise to help.

Following the second stasimon[6]—in which the Chorus sings of their upcoming role in the blinding of the Cyclops and their subsequent return to Dionysus—Polyphemus reenters with Odysseus and Silenus, who are plying him with wine. Silenus tries to sneak a drink from the Cyclops’ supply, and the Cyclops reprimands him.

As the Cyclops becomes more inebriated, he imagines that he is Zeus and that Silenus is his Ganymede. The scene ends with the Cyclops dragging Silenus into the cave.

In the third stasimon, the Chorus sings again of the blinding of the Cyclops. But when Odysseus returns and tells them it is time to go through with the plan, the satyrs back out one by one, claiming they are injured. Odysseus realizes he will have to blind the monster without them and returns to the cave.

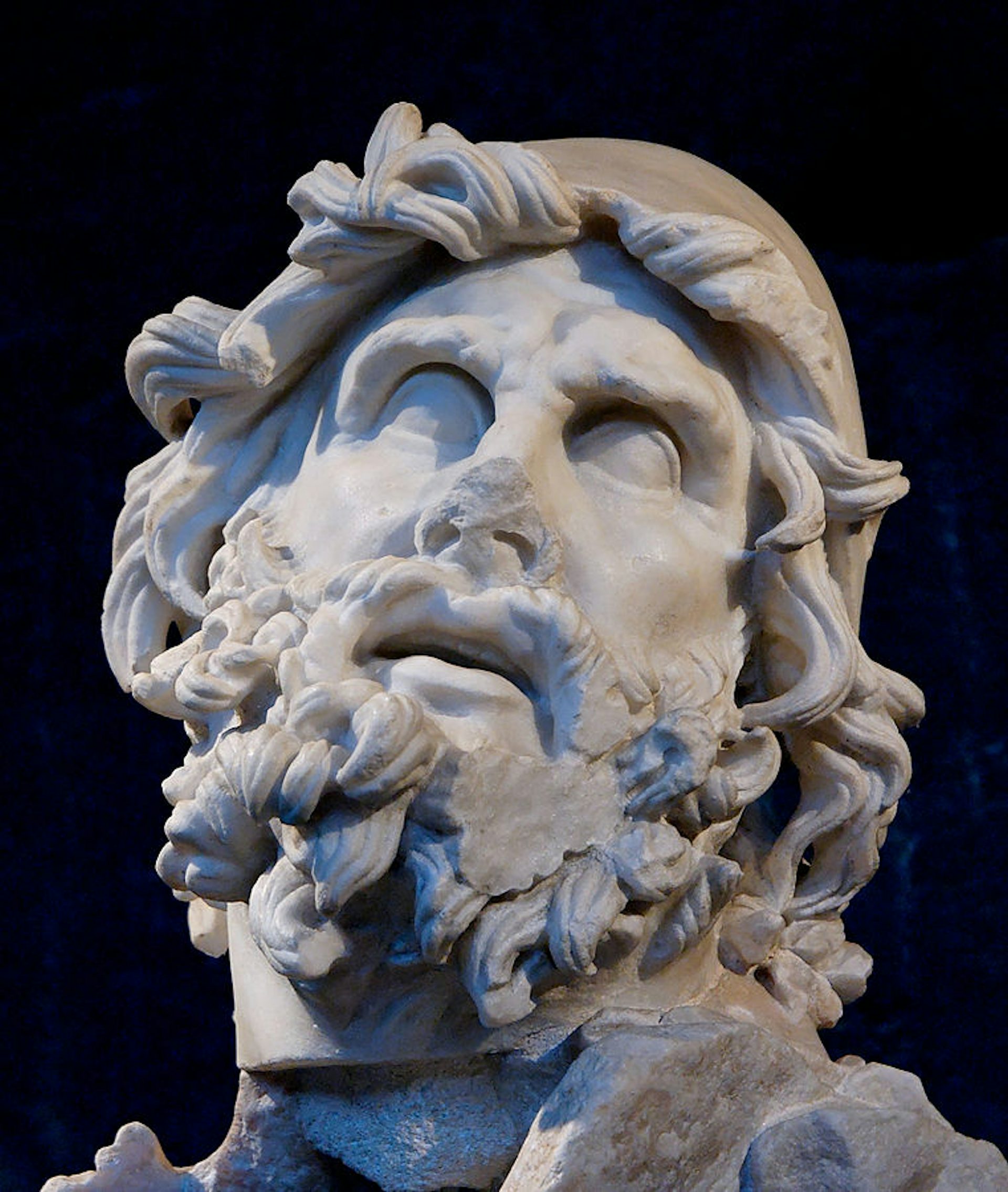

Head of Odysseus from a sculptural group showing the blinding of Polyphemus (1st century CE). From the Villa of Tiberius at Sperlonga.

National Archaeological Museum, Sperlonga / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainThe Cyclops emerges from the cave, blinded and crying out in pain. The Chorus mocks him, and Odysseus steps forward and reveals his identity. The Cyclops recognizes Odysseus’ name from a prophecy, which stated that a man named Odysseus would blind him before wandering the seas for many years as a punishment.

As everyone leaves the stage, the Chorus sings of their eagerness to return to the service of Dionysus.

Style and Composition

In recent years, most scholars have come to the consensus that 408 BCE was the date of performance for Euripides’ Cyclops (though some earlier scholars had posited an earlier date). This would mean that the Cyclops was performed within the same tetralogy as Euripides’ Orestes.

The Cyclops is the only intact example of a satyr play from antiquity. Satyr plays were performed at the end of every tetralogy, following three tragedies. They were marked by a burlesque and light tone and the presence of a chorus of satyrs—half-human and half-horse attendants of Dionysus.

Statue of an actor playing Papposilenus, Roman copy (ca. 100 CE) after a Greek original from the 4th century BCE

Altes Museum, BerlinPublic DomainThemes

Language—and its diverse uses—is an important theme throughout the Cyclops. Indeed, the way different characters make use of language contributes significantly to their characterization. Odysseus is clever and rhetorical, using language to outsmart the stronger Cyclops. Silenus, by contrast, is spineless and dishonest, misrepresenting his accomplishments and even lying about Odysseus’ intentions in an effort to save his own skin. The Cyclops is above all a blusterer, blasphemously placing himself above the gods.

The gods’ role in the world, and their relationship with lesser beings, also emerges as a prominent theme. Silenus and the satyrs boast a familiar but reverential relationship with Dionysus, the god of wine whom they serve. The Cyclops, on the other hand, views himself as a god and scoffs at the traditional pantheon, which he does not see as a threat. Odysseus, meanwhile, makes some show of piety, though his religiosity is not beyond reproach: whenever he prays to the gods, he always threatens to stop believing in them if they do not do as he asks.

Scholars have seen the play as a reflection of Athenian identity and values in the fifth century BCE. Odysseus, the Cyclops, Silenus, and the satyrs all represent different approaches to religious, cultural, and social values. Odysseus’ masculine and traditionally heroic ideal of courage in the face of adversity ultimately wins out, though other aspects of civic and religious identity are reflected in the other characters.

The Acropolis of Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

Neue Pinakothek, MunichPublic DomainReception

The Cyclops was never one of Euripides’ most popular plays. Indeed, it has survived only as one of the “alphabetic plays,” preserved in a fourteenth-century manuscript of Euripides’ works that was organized alphabetically rather than selectively or by popularity. The section of the manuscript with titles beginning with the Greek letter “kappa” (the first letter of the play’s Greek title) happened to survive, which is why we are able to read the Cyclops today.

In contrast to the play itself, the Cyclops’ subject matter—the myth of Odysseus and the Cyclops—remained very popular throughout antiquity, especially during the Roman Empire. Roman authors of the Age of Augustus, including Ovid, were particularly fond of reimagining the Cyclops Polyphemus as a lovesick creature. They depicted him hopelessly pining for the beautiful nymph Galatea—a love doomed to end in violence and heartbreak.

Fresco depicting the meeting of Polyphemus and Galatea, painted in the "Fourth Style" (45–79 CE)

National Archaeological Museum, NaplesPublic DomainSubsequently, there was little interest in Euripides’ Cyclops until the nineteenth century, when Percy Bysshe Shelley translated the play for a performance with his circle of literary friends in 1819. Since then, there have been more and more translations and adaptations, such as the 2011 Cyclops: A Rock Opera, produced by Psittacus Productions.

Translations

Translations of the Cyclops are usually found in volumes of Euripides’ collected plays. The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Kovacs, David, ed. and trans. Euripides, Vol. 1: Cyclops, Alcestis, Medea. Loeb Classical Library 12. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994: Accurate prose translation with facing Greek text; can be read online through the Perseus Project.

Morwood, James, trans. Euripides: Heracles and Other Plays. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: Accurate and idiomatic prose translation with useful notes and references.

Davie, John, trans. Heracles and Other Plays. Edited by Richard B. Rutherford. London: Penguin, 2003: Accurate and idiomatic prose translation, best suited to more knowledgeable readers.

Arrowsmith, William, trans. Euripides V: Bacchae, Iphigenia in Aulis, The Cyclops, Rhesus. 3rd ed. Edited by Mark Griffith and Glenn W. Most. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013: Readable and accurate verse translation with a basic introduction and notes (originally published in 1960).

O'Sullivan, P., and Christopher Collard, eds. Euripides: Cyclops and Major Fragments of Greek Satyric Drama. Aris and Phillips Classical Texts. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2013: Accurate translation, keyed to commentary, with facing Greek text.