Cadmus

Cadmus Sowing the Dragon's Teeth by the workshop of Peter Paul Rubens (between 1636 and 1700)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainOverview

Cadmus was a prince and hero born in the eastern Mediterranean. As a young man, he was forced to leave home in search of his sister (or niece) Europa, who had been carried off by Zeus.

After Cadmus had scoured the earth and finally exhausted his search, he decided to settle in Greece. On a fertile site in the region of Boeotia, he fought and killed a dragon, sowed a race of men who were born from the earth, and founded a new city, which he called Thebes.

Cadmus ruled Thebes for many years and had many children, though most of them died horrible deaths. Eventually, he and his wife Harmonia left Thebes and were transformed into serpents.

Who were Cadmus’ parents?

Ancient authorities named Cadmus’ father as either Agenor or Phoenix; his mother’s name varied considerably across sources. Cadmus’ parents ruled a kingdom in the eastern Mediterranean, usually thought to be located in the region of Phoenicia (modern Lebanon).

As the son of either Agenor or Phoenix, Cadmus was either the brother or uncle of Europa, a beautiful maiden who was abducted by Zeus.

Cadmus Sowing the Dragon's Teeth by the workshop of Peter Paul Rubens (between 1636 and 1700)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainWhat happened to Cadmus’ sister?

In most traditions, Cadmus’ sister was said to be the beautiful Europa (though some sources made her his niece). Europa was seduced by Zeus, who turned himself into a bull and whisked her away to Crete. There, Europa gave birth to the future kings of Crete.

Cadmus and his brothers were sent to find Europa. When they failed to do so, each of them settled down and founded their own kingdom.

The Abduction of Europa by Félix Vallotton (1908)

Kunstmuseum BernPublic DomainWhy was Cadmus turned into a snake?

In a story known from Euripides’ Bacchae, Dionysus—the god of wine—transformed Cadmus into a snake for failing to properly acknowledge the god’s divinity. Though Cadmus was Dionysus’ maternal grandfather, he and his family denied the god, thus inviting his wrath.

As a snake, Cadmus was forced to wander the Greek world. But even in his transformed state, he managed to lead a large barbarian army, which plundered the Greek cities in its wake.

The Dionysus Cup by Exekias (ca. 530 BCE), showing Dionysus sailing in a ship with dolphins

MatthiasKabelCC BY-SA 3.0Cadmus and the Foundation of Thebes

When Cadmus failed to find his lost sister Europa, he settled down in Greece. He decided to found a new city on a site he’d been led to by an oracle.

But before he could settle down, Cadmus had to fight a terrible dragon. After defeating the creature, Cadmus sowed the dragon’s teeth in the ground, and a race of earth-born warriors sprang up and fought one another. The survivors became the first inhabitants of Cadmus’ city, which he called Thebes.

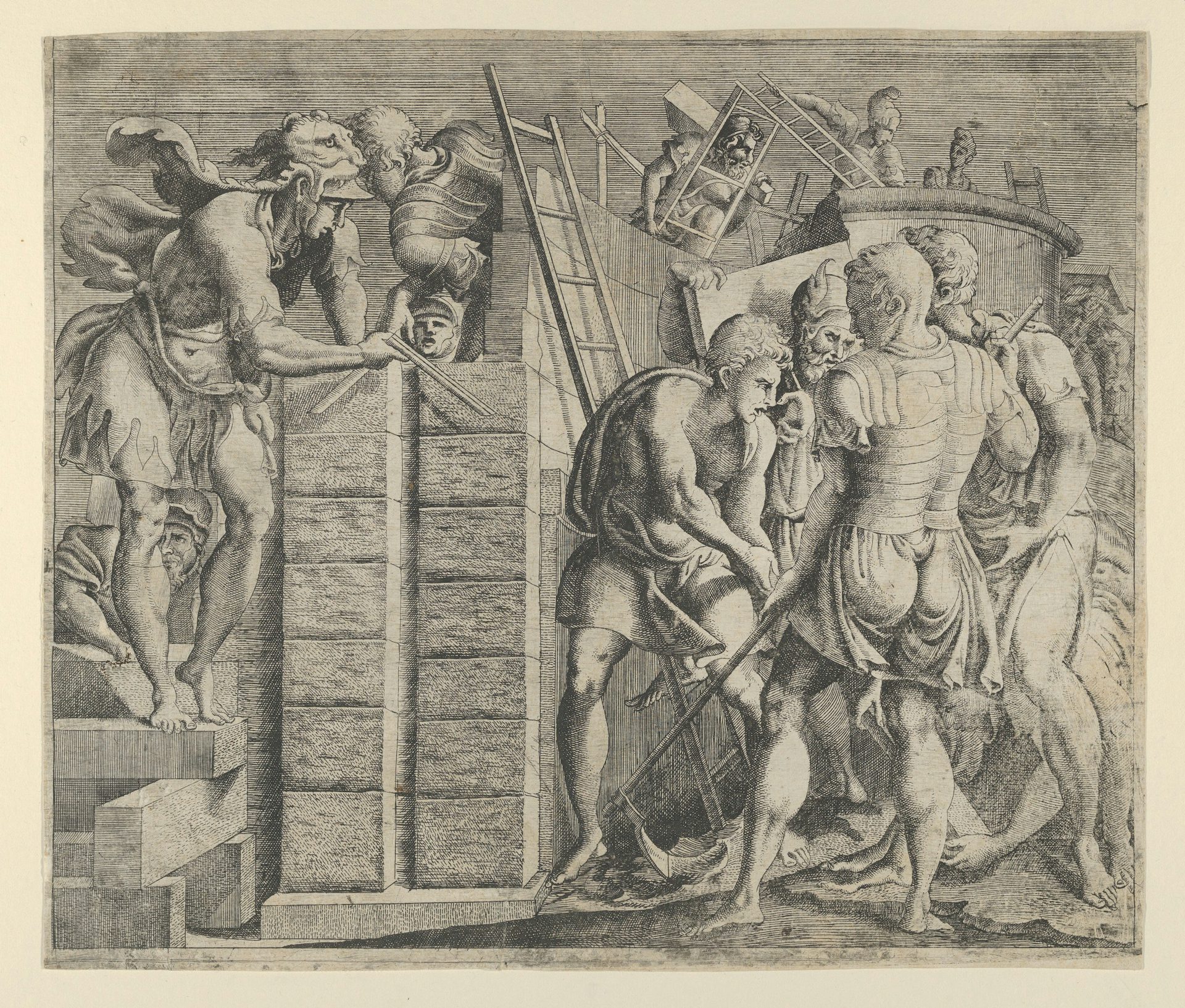

Cadmus Building Thebes, etching attributed to the Master of the Story of Cadmus, after Francesco Primaticcio (ca. 1542–1545)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEtymology

The etymology of the name Cadmus is uncertain. It has been connected to the Semitic root qdm, which means “east” (a fitting name, given that Cadmus was from the east). It has also been linked to the Greek verb kekasmai (“to shine”). However, linguist Robert Beekes rejected these derivations and deemed the name pre-Greek.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Cadmus Κάδμος Phonetic

IPA

[KAD-muhs] /ˈkædməs/

Attributes

Cadmus’ most famous heroic act was killing the dragon that guarded the sacred Ismenian Spring on the site of Thebes. This scene was sometimes represented in ancient art, though depictions of Cadmus are scarce.

Red-figure calyx-krater showing Cadmus fighting the dragon found in Sant'Agata de' Goti (ca. 350–340 BCE)

Louvre Museum / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainAfter killing the dragon, Cadmus came into possession of its magical teeth. He used these teeth to sow the race of warriors who would inhabit his new city. Eventually, Cadmus and his wife Harmonia were transformed into serpents or dragons themselves.

Family

The genealogy of Cadmus is hopelessly tangled: ancient sources give different accounts of his parents, siblings, and even his children.[2] These sources also disagree on the location of Cadmus’ homeland, which was variously identified as Phoenicia[,3] Tyre[,4] Sidon[,5] or even Thebes in Egypt.[6]

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins and Search for Europa

According to the best-known versions, Cadmus was born in Phoenicia on the east coast of the Mediterranean. His father was the king of the Phoenicians, named either Agenor or Phoenix.

Cadmus had a sister (or a niece, according to other versions) named Europa. One day, Europa was walking along the coast and caught Zeus’ eye. Zeus transformed himself into a beautiful bull and approached her. When Europa got on top of him, he carried her away across the sea to the island of Crete.

The Rape of Europa by Titian (1560–1562).

Isabella Stewart Gardner MuseumPublic DomainAfter Europa disappeared, her father sent Cadmus to look for her. Cadmus was accompanied by several companions and relatives, including his brother Thasus, but though they traveled extensively, they never found Europa. When he and the search party reached Samothrace, a region north of the Greek peninsula, Cadmus’ brother Thasus decided to settle down and founded the city of Thasos.[16] Cadmus, however, kept traveling.

Thebes

When Cadmus reached Greece, he learned from an oracle that he was to stop searching for Europa. The oracle gave him instructions on where to found a new city:

“When on the plains

a heifer, that has never known the yoke,

shall cross thy path go thou thy way with her,

and follow where she leads; and when she lies,

to rest herself upon the meadow green,

there shalt thou stop, as it will be a sign

for thee to build upon that plain the walls

of a great city: and its name shall be

the City of Boeotia.”[17]

Cadmus did as he was told. He followed a cow until it stopped to rest near a sacred body of water called the Ismenian Spring.

Cadmus was overjoyed and wished to sacrifice the cow to Athena. But when he sent some of his companions to draw water from the spring, they were killed by the dragon that was guarding it. After a lengthy struggle, Cadmus managed to defeat the dragon.

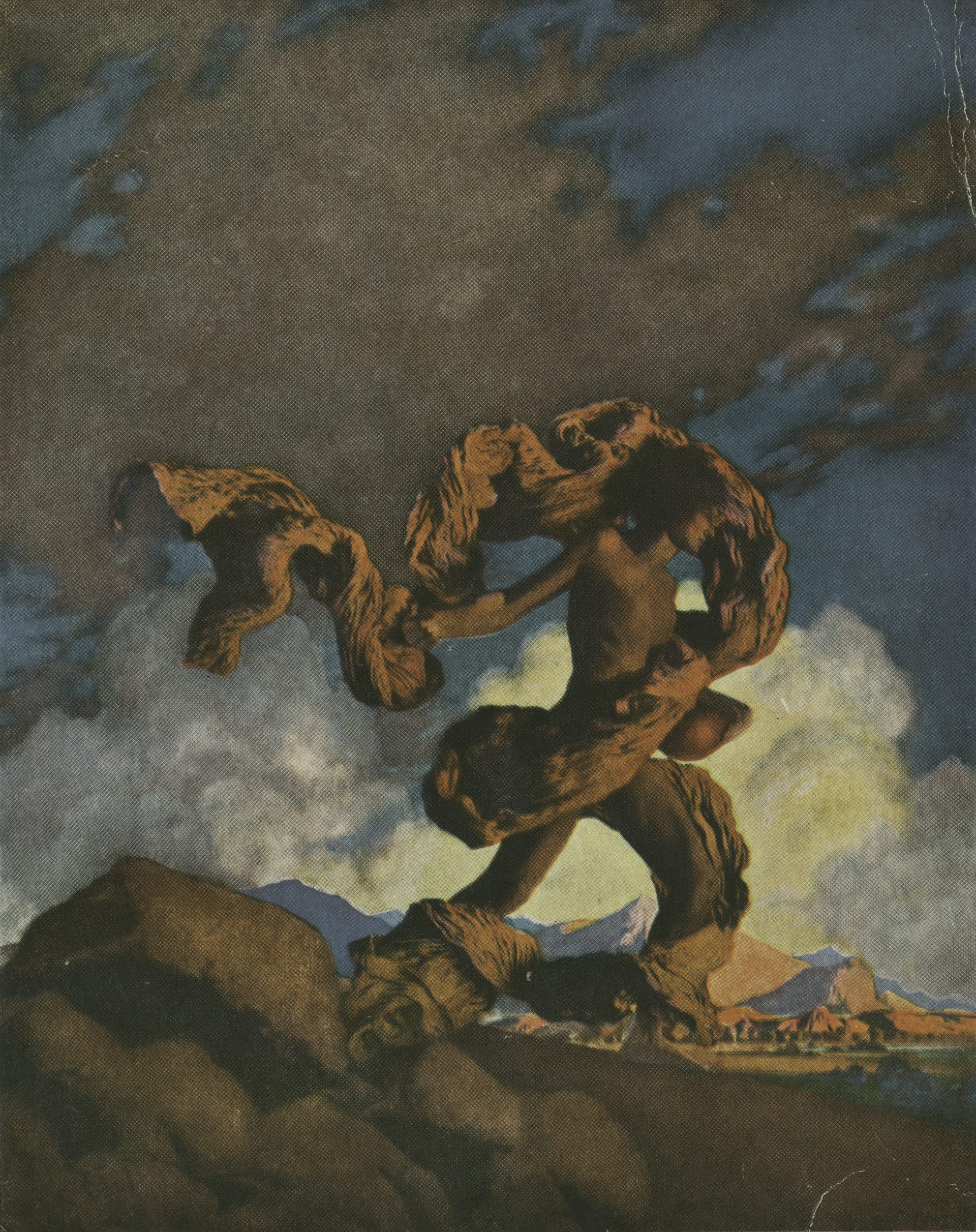

Cadmus Sowing the Dragon's Teeth by Maxfield Parrish (1908).

New York Public LibraryPublic DomainAs Cadmus mourned the loss of his companions, Athena (or Ares, in some versions) came to him and told him to sow the dragon’s teeth. Cadmus did so, and a race of warriors emerged fully grown from the earth. Following Athena’s instructions, Cadmus threw a boulder at the warriors. This caused them to start killing each other.

In the end, five warriors were left alive: according to ancient sources, their names were Echion, Udaeus, Chthonius, Hyperenor, and Pelorus.[18] These five helped Cadmus to found Thebes, and they and their descendants were called the Spartoi (“sown men”).

Harmonia

After founding Thebes, however, Cadmus needed to atone for the killing of the Ismenian dragon, which was sacred to Ares, the god of war. Cadmus therefore served Ares for a period of eight years.

In most sources, Cadmus was given Ares’ daughter Harmonia as a bride in return for his faithful service.[19] But according to the first-century BCE historian Diodorus of Sicily, Harmonia was the daughter of Zeus (not Ares), and Cadmus had married her in Samothrace.[20]

Whatever the case, the wedding of Cadmus and Harmonia was a grand affair. All the gods attended. As a wedding gift, Harmonia received a magical necklace that granted its wearer eternal youth. But the Necklace of Harmonia, not unlike the equally coveted Ring of Andvari of Norse mythology, brought nothing but grief to all who owned it.

The House of Cadmus

Cadmus was destined to witness the deaths of many of his children and grandchildren.

One of Cadmus’ daughters, Semele, was a lover of Zeus and became pregnant with the god’s child. But Zeus’ jealous wife Hera plotted against Semele. At Hera’s urging, Semele made Zeus reveal himself to her in his true form: a blazing bolt of lightning. As she was merely a mortal, this caused her to burst into flames. Zeus was able to rescue Semele’s child and sew him into his own thigh until he came to term. This was how the god Dionysus was born.[21]

Another one of Cadmus’ daughters was Autonoe. Her son, named Actaeon, stumbled upon the virginal goddess Artemis one day while he was hunting. Artemis was humiliated that a mortal saw her in the nude. As punishment, she turned Actaeon into a stag, and he was torn apart by his own hunting dogs.[22]

Cadmus’ daughter Ino, in many traditions, incurred Hera’s hatred because she nursed the infant Dionysus after her sister Semele was killed. Since Dionysus was the illegitimate child of her husband, Zeus, Hera wanted to destroy him and all who loved him (she tried to do the same to Heracles). Thus, Hera drove Ino and her husband Athamas mad, leading Ino to leap into the sea with her son Melicertes. Zeus took pity on her and turned her into the goddess Leucothea.

Finally, the son of Cadmus’ daughter Agave, Pentheus, refused to worship Dionysus when he became a god. Dionysus proved his divinity in a terrible way: he turned Agave into a maenad and caused her to tear her own son Pentheus apart with her bare hands.

Illyria

After suffering these domestic tragedies, it was usually said that Cadmus and Harmonia went to the land of the Encheleans (modern Albania). The Encheleans at the time were being attacked by the neighboring Illyrians and had learned from an oracle that they could only win the war if they made Cadmus their king.

Sure enough, the Encheleans defeated the Illyrians with Cadmus’ leadership, and Cadmus went on to reign over both kingdoms. He had another son, named Illyrius, who succeeded him in Illyria and went on to found several cities.

Metamorphosis

In antiquity, most traditions had it that Cadmus was transformed into a serpent or dragon sometime after fighting the Illyrians. This metamorphosis was sometimes understood as penance for killing Ares’ dragon years before. Zeus then sent the transformed Cadmus and Harmonia to the Elysian Fields.[23]

In this 17th-century Dutch etching of a scene from Ovid's Metamorphoses, Cadmus and his wife Harmonia hug each other as they are turned into serpents.

RijksmuseumPublic DomainAccording to Euripides’ tragedy Bacchae (ca. 405 BCE), however, Cadmus and Harmonia had been transformed into serpents earlier, while still in Thebes. In this version, Dionysus was responsible for the metamorphosis: this was part of his punishment of the Thebans for failing to worship him after he became a god. In their new serpent form, it was decreed that Cadmus and Harmonia would lead a foreign race in a war against Delphi.[24]

Worship

Cadmus received worship in some parts of ancient Greece. In Sparta, there was a heroum (hero shrine) dedicated to him.[25]

Pop Culture

Cadmus rarely appears in modern pop culture. He does not feature in any major films or TV shows with mythological subjects. The myth of Cadmus is, however, at the heart of Roberto Calasso’s 1993 novel The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony.

In the world of the Percy Jackson series, Cadmus is the namesake of Cadmus Hunter, and the myth of Cadmus is retold in Percy Jackson’s Heroes.

The “Cadmus Group” is the name of a strategic and technical consulting firm based in Massachusetts.