Brahma

Overview

The four-faced god Brahma is widely represented throughout Hindu and Buddhist mythology. When not serving as the creator god, he usually acts as an advisor to his fellow deities. Many of his appearances in myth involve him playing the role of a generous lord who gives out gifts, boons, and blessings to those who practice enough austerities and asceticism to impress him. The time it takes to impress Brahma can be cosmically long—sometimes only hundreds of years, but more often hundreds of millions of years.

Often these gifts and blessings are the inciting incidents for further myths. For instance, demons and titans gain blessings that render them nearly indestructible, and even the gods suffer in their fights against them. As a result, the gods must concoct complicated plans in order to kill the demons without violating Brahma’s blessings.

Gouache painting of four-headed Brahma riding on his vahana, or vehicle, a goose or swan. In his hands he holds a water vessel and a book. His other hands are in Abhaya Mudra and Varada Mudra, gestures for dispelling fear and giving out blessings. He is seated in lalitasana, or sporting pose, showing that he is relaxed but ready to stand at a moment's notice. Tamil Nadu. 1830.

Trustees of the British MuseumPublic DomainOne such story sees Brahma granting the demon Hiranyakashipu the ability to no longer be slain during the day or night, by a man or animal, on the ground or in the sky, or by any weapons. Hiranyakashipu used his near invincibility to conquer the cosmos. In the end, Vishnu incarnated as the avatar Narasingha (“Man-Lion”) in order to defeat the demon despite these stipulations: Narasingha, being neither man nor animal, killed Hiranyakashipu with his claws (without weapons), holding him in place on his thigh (neither on the ground nor in the sky).

By the time of the epics and the Hindu Puranas, Brahma’s stature and importance had declined in favor of other Puranic gods, such as Shiva, Vishnu, and Ganesha. Today there are only a handful of temples devoted to Brahma in India, though there are others throughout Southeast and East Asia devoted to the Buddhist Brahma.

According to the Brahmavaivarta Purana, this unpopularity is the result of a curse on Brahma by the sage Narada, who declared that Brahma would remain largely unworshipped for three eons before gaining worshippers again. Another story from the Skanda Purana claims that his unpopularity comes from Shiva’s curse, which he laid on Brahma for having lied to the other gods.

Etymology

The origins of the name “Brahma” are more complicated than those of other Hindu figures such as Shiva (“Auspicious”) or Ganesha (“Lord of the Ganas”). What is certain is that the name shares semantic overlap with other notable words in Hinduism—in particular, Brahman and Brahmin.

Upanishadic literature, which sprung up around 500 BCE, posits the existence of a universal, genderless, and all-pervading essence to the universe and all beings within it, which it calls “Brahman.” The creator god Brahma is popularly characterized as a personification of that essence. Brahmins, on the other hand, are the priestly caste of traditional Indian society, responsible for reciting and passing down Vedic and Brahmanical knowledge.

The distinctions between Brahma, Brahman, and Brahmin are blurred at times; for example, Brahma is often depicted as a wizened old sage with a beard and a white thread worn across his body—a symbol of the Brahmin caste. Brahma’s general demeanor and reputation likewise fit the sagely archetype.

It is likely that all three terms derive from the Sanskrit verb root √br̥h or √br̥ṃh, meaning “swell, grow, increase, be thick,”[1] which carries connotations of holiness across Indian religions. In Hinduism, for example, brahmacharin refers to a young and unmarried Brahmin who is still a student studying the Vedas, while in Buddhism, brahmachariya refers to someone on the religious path leading to liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

Pronunciation

English

Sanskrit

Brahma or Brahmā ब्रह्मा Phonetic

IPA

[Bruh-HMAH] /brɐɦmaː/

Titles and Epithets

Pitāmaha (पितामह), “Grandfather”

Hiraṇyagarbha (हिरण्यगर्भ), “Golden Embryo”

Prajāpati (प्रजापति), “Father of Beings”

Padmaja (पद्मज), “Lotus-Born”

Svayambhu (स्वयम्भु), “Self-Born”

Attributes

Brahma’s most striking visual characteristics are his red skin, four arms, and four heads, representing either the four cardinal directions or the four Vedas. Unlike the other gods of the Hindu trimurti, Brahma does not usually carry weapons; instead, he is often portrayed carrying a water jug, a mala (rosary), a ladle, a book, and/or a lotus. In addition, he sometimes displays the abhaya mudra, the gesture for dispelling fear. He is usually depicted sitting on a lotus or a swan, which serves as his vahana, or vehicle. Sarasvati, goddess of learning and the arts, is his wife.

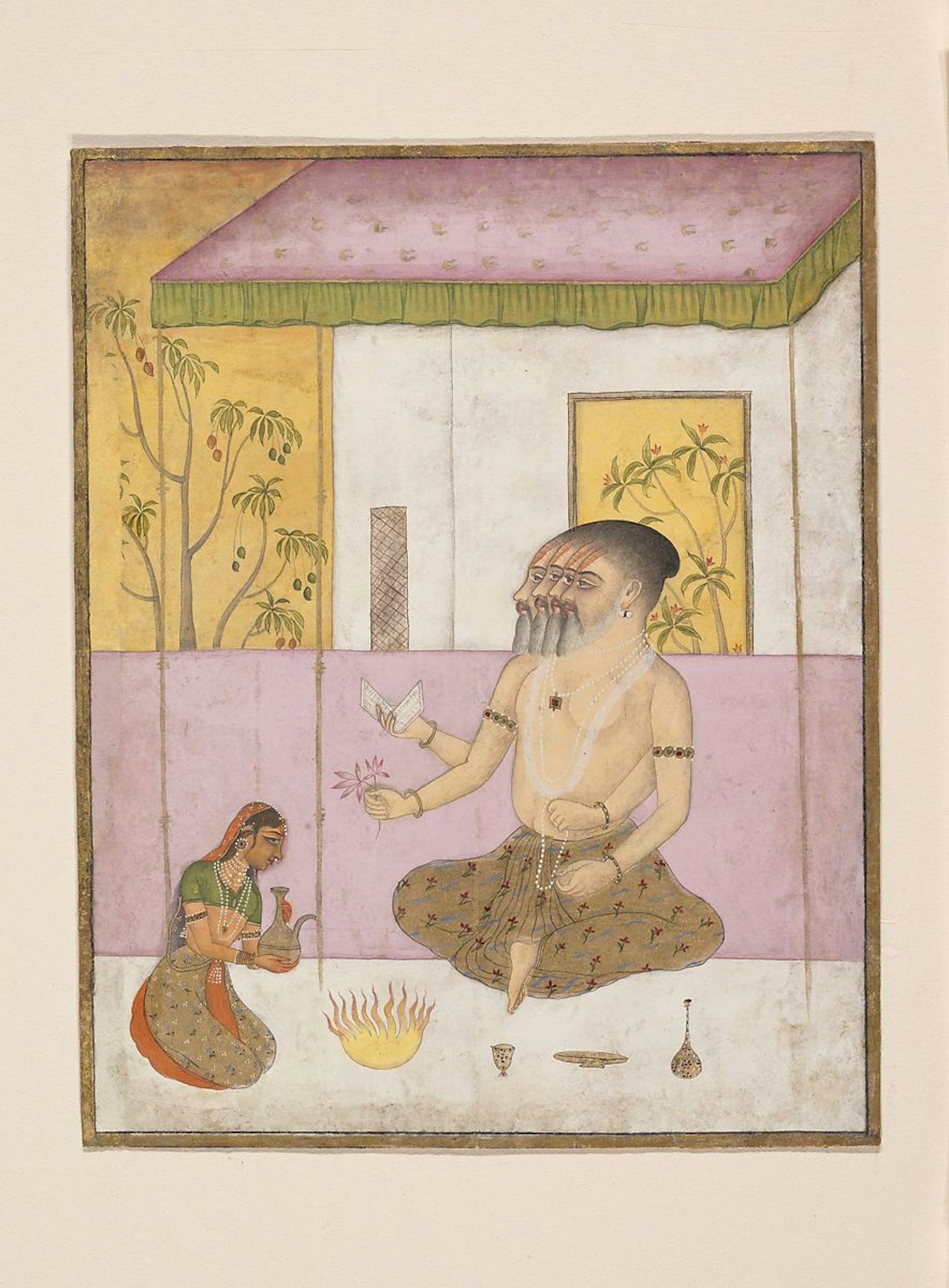

Rajasthani painting of a female worshipper offering an oblation to Four-headed Brahma. In his hands he holds a rosary, a book, and a lotus. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ca. 1675.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainDomains

Brahma is chiefly regarded as the god of creation, but he is also closely associated with sagehood, wisdom, Brahmins, and the Vedas.

Family

Family Tree

With one of his most popular nicknames being Pitāmaha, or “Grandfather,” Brahma is responsible for an untold number of children. The entire human race could be considered his children, as he created the first man and woman. There are, however, a number of people that Brahma played a more direct part in creating, notably his nine “mind-born” sons (listed below) and innumerable sages and priests.

Consorts

Wives

- Sarasvati

- Savitri

Children

Daughter

Sons

- Shatarupa

- Bhrigu

- Vasishtha

- Atri

- Pulastya

- Marichi

- Daksha

- Angiras

- Kratu

- Pulaha

- Sanaka

- Sananda

- Sanatana

- Sanatkumara

- Manu

- Arani

- Vodhu

- Narada

- Prachetas

- Hamsa

- Yati

Mythology

Origins

Brahma appears only sporadically in the earliest texts of Hindu literature, the Vedas and Brahmanas. Indeed, it is not Brahma but two other figures—Prajapati and Purusha—who play the role of universal creator in these early texts. It is only with the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad that Brahma first appears in his function as creator, and even then only at the end.[3] Later Puranic texts equate him with the established Vedic figure of Prajapati, much like Shiva was identified with the earlier Vedic Rudra.

Greg Bailey notes that Brahma is listed as a deva (god) in the Shatapatha Brahmana and occurs “several times in the Āraṇyakas and the early and middle Upaniṣads.”[4] Thus, by the eighth century BCE, he was at least recognized as a god.

There is significant evidence that Brahma became a popular and widely worshipped god in Indian religions, notably Hinduism and Buddhism. He appears regularly in the Pali canon of Buddhist literature (beginning in the sixth or fifth century BCE), often mentioned as foremost among the gods, along with Indra. Given his prominence in early Buddhist literature and Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata, Brahma must have risen in importance over the three centuries between the late Vedic and Brahmanic texts and the beginnings of Buddhism and epic literature.

Though his presence in Puranic myths is unmistakable, it is clear that Brahma’s worship had sharply declined in popularity by the time of the Puranic texts. Indeed, while the other members of the Hindu trimurti, Shiva and Vishnu, continue to be widely worshipped to this day, only a handful of Brahma’s temples have survived in India.

According to A. L. Basham, this may be partly due to the fact that Brahma’s major functions and deeds—creating the universe and transmitting the Vedas—are already done. In other words, his actions play little part in the life of ordinary Hindus. By the time of the Puranic myths, “Brahma was a god associated with things of remote antiquity, and was not very active at this stage of the world’s history.”[5]

Brahma and the Cosmic Egg

According to Hindu mythology, long ago the world was nothing but water, and on this water rested a giant golden egg. Brahma the creator slept within this egg for a thousand ages before finally emerging as the first being in existence. For this reason, Brahma is also known as Hiranyagarbha, or “Golden Embryo.” Because all of creation was held within the egg, when Brahma broke free he also released the potential for all manner of beings: humans, gods, daityas (demons), asuras (titans), lands, oceans, and islands.

Brahma Creates Women

According to one tale in the Hindu epic the Mahabharata, Brahma created lustful women in order to distract men. As the story goes, men and women were once full of virtue and dharma (righteousness), which made the gods fearful. If these humans meditated too effectively, they would in time grow powerful enough to challenge even the gods in the heavens. Thus, the gods set out to humble humans.

Brahma’s solution to this problem was simple: “The lord Grandfather, learning what was in the hearts of the gods, created women by a magic ritual in order to delude mankind.”[6] He gave these “sinful sorceresses” every desire imaginable so that they would in turn agitate men and keep them from their meditations. But the creator god was not done; he next made anger to work alongside desire. All beings then fell under the sway of desire and anger, and the gods were no longer in danger of being overthrown.

Brahma and Vishnu

A commonly depicted scene in Hindu art shows the god Brahma sitting on a lotus growing out of the preserver god Vishnu’s navel. As Vishnu was resting on the cosmic ocean after one of the regular and cyclical dissolutions of the universe, Brahma approached him and asked who he was. Vishnu responded that he was the originator and dissolver of worlds, and he urged Brahma to look inside him to see all the universe within him. Brahma responded, “I am creator and ordainer, the self-existent great-grandfather; in me is everything established; I am Brahmā who faces in all directions.”[7]

After searching the inner depths of Brahma’s body, Vishnu was astonished to find that Brahma indeed held all the worlds, with its gods, mortals, and demons, within him. The creator god did the same, jumping into Vishnu’s cosmic form and finding no end or beginning to all the worlds contained within him. Seeing no other way out of that oceanic space, he escaped through Vishnu’s navel and landed on the gigantic lotus growing out of it. For this reason, Brahma is nicknamed Padmaja, or “Lotus-Born.”

Brahma Milks the Earth and Creates the Varnas

Several texts tell the story of how human society fell from its golden period into a dark age of immorality, and how Brahma created the Varna system, or caste system, to slow this decline. According to the Markandeya Purana, the cosmic cycle had just transitioned away from the Kritayuga and reached the Tretayuga, an age in which humans no longer acted morally without prompting or convincing.

During the former Kritayuga, humans had lived for four thousand years and had all their needs met without needing to farm, hunt, or gather. Now, desire and avarice spread, humans built fortresses and cities for protection, lifespans shortened, and they harassed each other in their struggle to live. Afflicted with hunger and at a loss for what to do, they approached Brahma for counsel.

Knowing that the earth had withdrawn her bounty, Brahma milked the earth, and from it sprang cereals and plants of all kinds. He then ordained that humans would farm and cultivate these plants according to their station—which was determined by their relationship to Brahma’s body.

When Brahma first created humanity, he did so through his own body parts: a thousand human pairs spilled out of his mouth. Another thousand pairs spilled out of his chest. A thousand more spilled from his thigh. Lastly, a thousand spilled from his feet. He now brought order to society through a hierarchical caste system based on which body part one’s ancestors had been born from: mouth, chest, thigh, or feet. Lastly, he established the four stages of a Brahmin’s life and laid out which afterlife was set aside for the different groups who behaved according to their station.[8]

Brahma Creates the Universe

By the time of the epics and the later Puranas (ca. 200 CE), Indian religions had developed to recognize the law of karma—seen, for example, in the Vishnu Purana’s account of Brahma’s creation of the universe. Here, karma is an immutable law of the universe affecting all creatures: animals, humans, demons, titans, and even gods.

Although all creatures are destroyed at each cosmic dissolution, they are not released from rebirth, but are reborn according to the reputation of their former good or bad karma...Thus the lord Brahmā, the First Creator and lord, created; and whatever karma they had achieved in a former creation, they received this karma as they were created again and again, harmful or benign, gentle or cruel, full of dharma or adharma, truthful or false. And when they are created again, they will have these qualities; and this pleased him.[9]

This version of creation makes use of three primal substances: rajas (passion), tamas (darkness), and sattva (goodness). By cycling through bodies composed of these substances and then discarding them, Brahma created innumerable things.

As he was concentrating on creation, tamas infused his body, and demons sprouted out of it. He discarded that body and it became the night. He took another body, this time infused with rajas, and the gods sprang out of his mouth. After he discarded that body, it became the day. He took a third body composed of sattva, and the ancestors (Sanskrit pitaras, “fathers”) were born. That body became the evening twilight. He took a fourth body made of rajas, and humans were born. That body became the morning twilight.

In this same way came hunger, rakshasas (demons), snakes, pishachas (another form of demons), and gandharvas (heavenly singers and dancers). However, Brahma did not make all of these beings intentionally, so he next set his sights on creating things of his own free will. From these efforts came birds, sheep, goats and other livestock, grasses, fruits, and vegetables.

At the beginning of every kalpa (eon), he repeats this process, and each creature inherits the karma accrued from actions in earlier lives.

Brahma’s Curse and Beheading

A number of tales mention a quarrel between Shiva and Brahma that led to Shiva either cursing the creator god or severing his fifth head.

One story says that after Brahma split himself into two so that the first male and female could be made, he became entranced with his sister/daughter/wife’s beauty.[10] The two mated, and humans were born. Not wanting to let her out of his sight, he grew three other heads so that he could always spy on the modest woman.

She eventually got fed up with his lecherous behavior and said, “How can he unite with me after engendering me from himself? For shame! I will conceal myself.”[11] And she took off into the sky in the form of a cow. Seeing this, Brahma grew a fifth head facing upward so that he could watch her in the sky as well.

But soon the creator god was not content to simply watch, and he pursued her across the sky in the form of a bull. From this assault, cows were created. She continued to transform into different animals, and he in turn took on the male forms of those animals and mated with her. In this way, all the various creatures of the earth were born.

Shiva, watching these pursuits in disgust, at last loosed an arrow from his bow. The shaft pierced through Brahma’s animal head so swiftly that it fell clean off, and Brahma was reduced to only four heads once more.

Another account of Brahma’s beheading appears in the Skanda Purana. This tale claims that after Shiva ordered Brahma to create the universe, Brahma spent a thousand years meditating in preparation. During this time, he eulogized Shiva, worshipped him, and contemplated his mysteries. In a curious twist to the usual trope of Brahma appearing to meditators, Shiva appeared to Brahma and offered him a blessing.

Brahma boldly asked for Shiva to be his son and for him to regard Brahma as his father. Enraged, Shiva cut off one of Brahma’s heads, saying that Brahma should not have asked for such a thing. But Shiva met Brahma’s request halfway: he drew out a part of himself named Nilalohita Rudra (“Purple Rudra”) to be Brahma’s son. But even this small part of himself, Shiva warned, would obscure Brahma’s luster.[12]

A different tale from the Skanda Purana speaks of a contest between Vishnu and Brahma to see if they could reach the top or bottom of a gigantic pillar of fire that had erupted before them. Vishnu could not reach the bottom no matter how far he traveled, and he admitted the truth. But Brahma, when he was unable to reach the top, lied to all the gods and said that he had plucked a flower from the tip.

After Brahma uttered this lie, Shiva strode out from the pillar of fire. For Vishnu’s honesty, Shiva decreed that he was to be worshipped just as much as Shiva was, with temples of his own. But as for Brahma, Shiva was not pleased. He created Bhairava, a manifestation of Shiva’s might, and ordered him to cut off the head that had tricked the gods. The being grabbed hold of Brahma’s hair and prepared to sever his fifth head.

The creator god shook so much in fear that his garland and clothes grew disheveled and were reduced to tatters. It was only Vishnu, begging for Shiva to spare Brahma, that saved his head (for the time being). But for Brahma’s lie, Shiva decreed that Brahma was to have no temples of his own, no festivals, and no worshippers. This is one explanation for why Brahma is so unpopular compared to Shiva and Vishnu.[13]

Haribhadra, the seventh-century Jain monk and scholar, told his own version of the tale. It begins with the gods gathered together discussing their lineage and the names of their mothers and fathers. When it was time to discuss Shiva’s parentage, no one seemed to know. But Brahma grew angry, saying that it was unbelievable that others would think he did not know; after all, he knew everything.

When the creator god began to open his mouth to announce the names of Shiva’s parents, Shiva sliced off his fifth head with the nail of his right little finger, using it as a sword blade. Thus, the secret of Shiva’s lineage was kept safe, and Brahma lost a head.

Brahma in Buddhism

Brahma appears widely in Indian Buddhist texts and shares some of the same characteristics as his Hindu equivalent. In both traditions, he is hailed as the creator of the universe; likewise, both traditions view creation as cyclical, occuring at the beginning of a cosmic age (Sanskrit kalpa, Pali kappa), after the dissolution of the old universe.

Brahma’s Place in Buddhist Cosmology

An important distinction between the Buddhist Brahma and the Hindu one is that in Buddhism, his status as a god is impermanent (as is the case with all Buddhist gods). Brahma’s life span may last for millions of years (or 84,000 kalpas), but he is ultimately subject to old age and death.[14] For this reason, it is more accurate to think of Brahma as a celestial status, a class of beings, or a position rather than a single, immortal, and self-arisen (Sanskrit svayambhu) being.

Brahma’s role in Buddhism is quite different from that of the Hindu Brahma. While the Hindu Brahma acts as a heavenly advisor to other gods and gives blessings and favors to those who impress him by performing austerities, the Buddhist Brahma does little to advise or grant blessings. The Buddha himself fills this role since he is the greatest of beings, ranked higher even than gods.

One of the few characteristics the two Brahmas share is their function as creator gods. However, this, too, is a tenuous connection: Brahma is rarely classified as a creator god in early Buddhist texts, and creation itself is relatively unimportant in the Buddhist worldview. Nevertheless, he remains a powerful god.

Korean painting on a hemp scroll of Brahma, or Beomcheon (center), surrounded by his attendants in his heavenly paradise. As conceived in Buddhism, Brahma rules over a heavenly kingdom of his own, a paradise of pleasures and music. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ca. late 16th century.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOne story in particular demonstrates Brahma’s more limited status in Buddhist traditions. At one time, the Buddhist monk Kevaddha sought answers to big cosmological questions such as the limits of the universe. Using his psychic powers gained through meditation, he visited various higher realms and heavens and asked the gods what they knew. When pressed for answers, each and every god eventually admitted that they did not know the limits of the universe, telling him to ask even more powerful beings. After making his way through all the different levels of gods, he eventually reached Great Brahma, who told him:

I am, oh monk, Brahma, the Great Brahma, conquering, unconquerable, all-seeing, mighty, the lord, the maker, the shaper, the best creator, the master, the father, and lord of all who are and will be.

Ahamasmi, bhikkhu, brahmā mahābrahmā abhibhū anabhibhūto aññadatthudaso vasavattī issaro kattā nimmātā seṭṭho sajitā vasī pitā bhūtabhabyānaṃ.[[object Object]]

But when pressed further, Brahma revealed that he, too, did not know the answers to such questions. He told Kevaddha to go and ask the Buddha, who was the only truly omniscient being in the universe. From this we can see that, according to the Buddhist worldview, Brahma’s claim that he is the greatest and wisest of all beings is nothing more than a delusional boast.

However, it is important to note that Brahma remains a god in Buddhism and is undoubtedly a wise and powerful being. Within the endless cycle of life, death, rebirth, and redeath, beings born as a Brahma are close to their final birth. And those beings who have the good fortune to be born as a Great Brahma, as in the story above, are likely on their final life before realizing nirvana.

Brahma and the Buddha

Despite his more minor status in Buddhism, Brahma is not a passive god. Just after the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, he was uncertain whether to share the Dharma, a collection of teachings on how to end suffering.[16] The truths he had discovered in his quest for nirvana were too difficult for most people to comprehend, he reasoned, and he would never be able to pierce through listeners’ delusions.

As the Buddha wrestled with these thoughts, Brahma appeared before him and urged him to teach:

Venerable one, may the Lord teach the Dhamma,[17] may the well-gone[18] one teach the Dhamma! There are those beings with only a little defilement. They dwindle because they haven’t heard the Dhamma. There will be those who understand the Dhamma.

desetu, bhante, bhagavā dhammaṁ, desetu sugato dhammaṁ. Santi sattā apparajakkhajātikā, assavanatā dhammassa parihāyanti. Bhavissanti dhammassa aññātāro’ti.[19]

Brahma argued that while most people would be unwilling or unable to put the Buddha’s teachings into practice, a few certainly would. It was for those few that the Buddha should teach. His words swayed the Buddha, who went on to share the Dharma and found the religion of Buddhism.

This story presents another peculiar subversion of the Hindu trope of Brahma appearing to ascetics to grant them blessings. Rather than grant the Buddha a wish because of his great meditations, in this tale it is Brahma who wants something from the Buddha: teachings leading to nirvana for all beings.

Bimaran Reliquary casket with images of the Buddha, Indra, and Brahma. A bearded and haloed Brahma (center) faces the Buddha while holding a water jug and raising his right hand. A second Brahma appears on the opposite side. Gandhara, ca. first century CE.

Trustees of the British MuseumPublic DomainLater Buddhist commentators paint this exchange in a different light. According to Buddhaghosa, writing in Sri Lanka in the fifth century CE, the Buddha orchestrated Brahma’s appearance from the beginning. Since Brahma was such a widely worshipped god (at least according to Buddhaghosa, looking back a thousand years), having the creator god come to earth and beg the Buddha to teach would lend the Buddha a degree of legitimacy and a divine seal of approval. It had the added effect of making it clear that the gods considered themselves to be beneath the Buddha in the cosmological hierarchy.

Worship

Festivals and/or Holidays

The Bonten Festival in Tochigi, Japan is held in late November in honor of Bonten, the Japanese Buddhist form of Brahma.

Temples

The Jagatpita Brahma Mandir temple, built alongside Lake Mandir in Pushkar, Rajasthan, is one of the few prominent temples devoted to Brahma in India.

Thanks to the spread of Buddhism across Southeast, Central, and East Asia, the Buddhist Brahma is more commonly worshipped outside of India. The Thao Maha Phrom Shrine in Bangkok, Thailand is a popular shrine to Phra Prohm (Mahabrahma, or “Great Brahma”) and boasts a golden statue of the four-faced god.

The worship of Brahma entered China and Japan through the spread of Buddhism. In China, one can find temples to Brahma under the name of Fan Tian (梵天). In Japan, Brahma developed into Bonten or Daibonten, commonly depicted along with Indra as an attendant of the Buddha.

Pop Culture

Brahma remains an established and respected god among Hindus throughout South and Southeast Asia, although not as popular as other figures such as Vishnu, Shiva, or Ganesha.