Balius and Xanthus

Automedon with the Horses of Achilles by Henri Regnault (1868)

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainEtymology

The names “Balius” (Greek Βάλιος, translit. Bálios; also spelled Βαλίας, translit. Balías) and “Xanthus” (Greek Ξάνθος, translit. Xánthos) were quite appropriate for horses, as they referred to their coloration. “Balius” means “dapple,” coming from the Greek word βαλιός (baliós), which itself seems to have originated in a non-Greek (probably Illyrian) word used to designate a dappled or spotted horse.[1] Xanthus’ name is even more straightforward and means “yellow, blonde, reddish-brown.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Balius, Xanthus Βάλιος (Bálios)/Βαλίας (Balías); Ξάνθος (Xánthos) Phonetic

IPA

[BAH-lee-uhs]; [ZAN-thuhs] /ˈbɑ li əs/; /ˈzæn θəs/

Attributes

Balius and Xanthus were immortal horses, known for their remarkable speed; Homer describes them as “swift as the winds.”[2] They were the most formidable of all the horses that took part in the Trojan War. Fittingly, they also belonged to the greatest hero of the war: Achilles.[3]

Family

Balius and Xanthus were born to the Harpy Podarge after she mated with Zephyrus, the god of the west wind, in the form of a mare.[4]

Mythology

Achilles and the Trojan War

The immortal horses Balius and Xanthus seem to have first belonged to Poseidon, the horse-loving god of the sea. Poseidon gave them to the hero Peleus as a wedding present when he married Thetis. Later, Peleus gifted the horses to his son Achilles when he went off to fight in the Trojan War.[5]

Balius and Xanthus drew Achilles’ chariot as the hero wreaked havoc on the plains of Troy. Sometimes they were yoked together with a third horse, Pedasus, who acted as a trace horse (Pedasus was mortal, but he was speedy enough to keep up with his immortal brethren). Balius and Xanthus were notoriously spirited and unwieldy, and only Achilles could fully master them—though Achilles’ charioteer, Automedon, also knew how to steer the beasts.[6]

Achilles’ horses were admired by all who fought in the Trojan War, Greek and Trojan alike. In one tradition, the Trojan warrior Dolon asked the Trojan commander Hector to award him Balius and Xanthus in exchange for going out to spy on the Greeks (Hector agreed, but poor Dolon did not survive to collect his reward).[7]

After Achilles ceased fighting because of his quarrel with the Greek commander-in-chief, Balius and Xanthus carried his best friend Patroclus into battle—clad in Achilles’ divine armor—to save the Greeks from annihilation. When Patroclus was killed by the Trojan champion Hector, Balius and Xanthus were inconsolable. They wept and refused to move until Zeus breathed vigor into them so that they could dash away to safety.[8]

When Achilles returned to battle in order to avenge his friend, he rebuked Balius and Xanthus for letting Patroclus die and charged them with keeping better watch over him. Remarkably, Balius and Xanthus understood their master’s words; Xanthus, temporarily granted the power of speech by the goddess Hera, even spoke to Achilles in response, promising that he and Balius would keep Achilles safe. But the horse also prophesied his master’s impending death:

“Aye verily, yet for this time will we save thee, mighty Achilles, albeit the day of doom is nigh thee, nor shall we be the cause thereof, but a mighty god and overpowering Fate… But for us twain, we could run swift as the blast of the West Wind, which, men say, is of all winds the fleetest; nay, it is thine own self that art fated to be slain in fight by a god and a mortal.”[9]

After he had said this, Xanthus’ voice was stopped by the Erinyes, the goddesses of fate, whose duty it was to prevent any transgressions against the natural order of things (such as talking horses).[10]

As predicted, it was not long before Achilles, too, was killed in battle. Balius and Xanthus mourned his death and even wished to leave the mortal realm forever; but the gods explained that it was their fate to serve one more master, Achilles’ son Neoptolemus, and to carry him to Elysium when he died.[11] Alternatively, another tradition claimed that Poseidon took the horses back after Achilles’ death.[12]

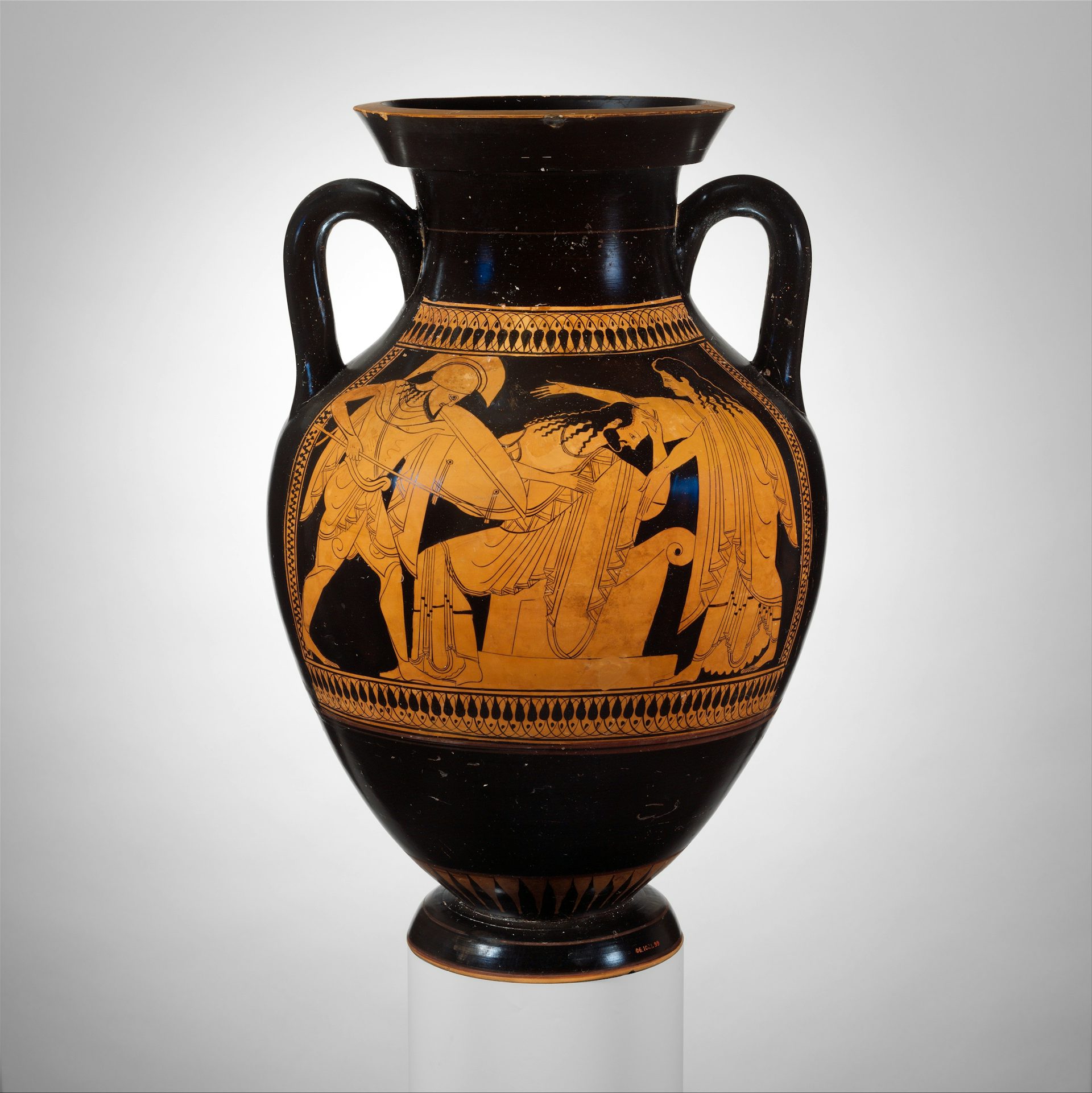

Attic red-figure amphora by the Nikoxenos Painter (ca. 500 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOther Myths

There were a handful of other, more obscure traditions about Balius and Xanthus. According to Diodorus of Sicily, Balius and Xanthus had originally been Titans. But when the Titans fought against the Olympians in the Titanomachy, Balius and Xanthus decided to switch sides and help the Olympians, asking first that they be changed into horses so that their brothers would not recognize them.[13]

In another strange account, Balius and Xanthus were originally either Giants or the horses of Giants. As in Diodorus’ account, Balius and Xanthus did not want to join the Giants in warring against the Olympians and allied themselves with the gods instead.[14]