Atalanta

The "Atalanta," a statue of a young girl (1st century BCE)

Vatican Museums / JastrowPublic DomainOverview

Atalanta was a female hero renowned for her speed and strength. She took part in many heroic exploits, often surpassing her male counterparts in physical prowess. In one of her most fateful adventures, she participated in the Calydonian boar hunt and inadvertently brought about the death of the hero Meleager.

When forced to marry, Atalanta would only agree to wed the man who could beat her in a footrace. Given her famous speed, this was no small feat, but one of Atalanta’s suitors finally managed to win her hand with the help of Aphrodite, the goddess of love.

Unfortunately, Atalanta was not destined to live out her days in wedded bliss: after gravely offending the gods, she and her husband were transformed into lions.

Who were Atalanta’s parents?

The name and identity of Atalanta’s father varied widely across ancient sources. He was sometimes said to have been an Arcadian ruler or prince named Iasus, Iasius, or Iasion, while in other traditions he was a Boeotian named Schoenus.

Abandoned by her father when she was still an infant, Atalanta grew up in the wild. She became a skilled hunter and fighter and was a favorite of the virginal goddess Artemis. Eventually, after achieving great fame as a hero, Atalanta was reunited with her father.

The "Atalanta," a statue of a young girl (1st century BCE)

Vatican Museums / JastrowPublic DomainWhom did Atalanta marry?

Atalanta married a young man from Boeotia named Hippomenes (or Melanion, depending on the source). She had announced that she would only marry the man who could beat her in a footrace. But Atalanta easily bested all of her suitors.

Hippomenes was able to finally win Atalanta’s hand with the help of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Aphrodite gave Hippomenes three golden apples, which the young man threw in front of Atalanta to distract her during the race. Through this trick, Hippomenes beat Atalanta and won her as his bride.

The Race between Hippomenes and Atalanta by Noël Hallé (between 1762 and 1765)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainWhy was Atalanta turned into a lion?

According to one myth, Atalanta and her husband profaned the temple of the goddess Cybele (or Rhea) by making love in it. Because of this sacrilege, they were both transformed into lions and harnessed to the goddess’s chariot.

Atalanta and Hippomenes transformed into Lions by Crispijn van de Passe (1602–1607)

RijksmuseumCC0Atalanta in the Calydonian Boar Hunt

Atalanta was one of the heroes who took part in the famous Calydonian boar hunt. This was a mission to hunt and kill the Calydonian boar, a monstrous creature that Artemis had sent to terrorize Calydon and punish the local king.

During the hunt, the Calydonian prince Meleager fell in love with the beautiful Atalanta. After killing the boar, Meleager wanted to give its hide to Atalanta as a prize, as she was the one who had drawn first blood. This act angered Meleager’s uncles; in the brawl that ensued, the prince killed his uncles. Meleager himself died shortly thereafter through the actions of his enraged mother.

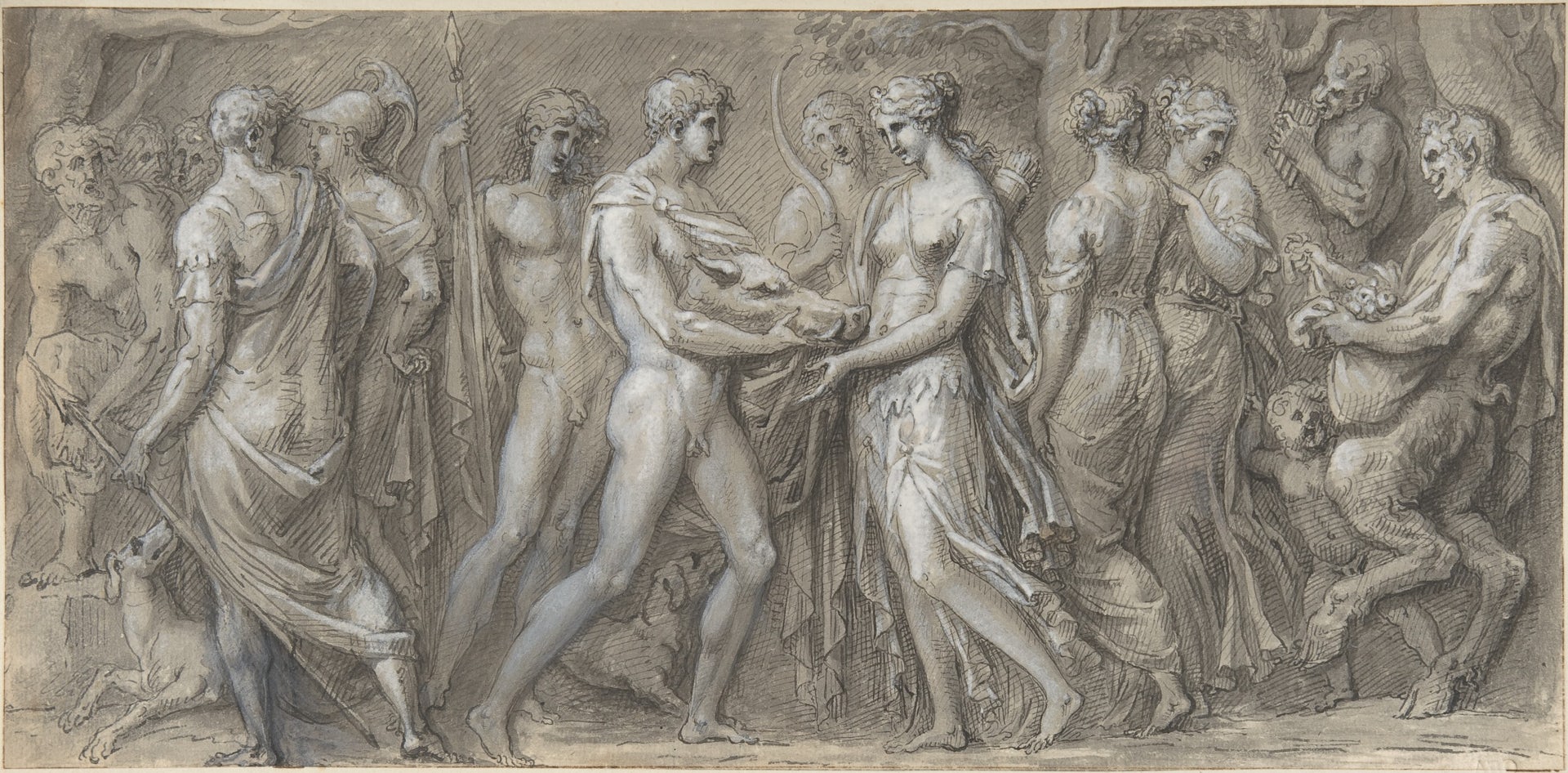

Meleager Presents to Atalanta the Head of the Calydonian Boar by Guillaume Boichot (ca. 1800)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEtymology

The name “Atalanta” seems to be related to the Greek verb *tlaō, meaning “to toil” or “endure” (itself derived from the Indo-European *telh₂-); the a- added as a prefix acts as an intensifier. Atalanta’s name thus means “she who toils greatly.”[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Atalanta Ἀταλάντη Phonetic

IPA

[at-l-AN-tuh] /ˌætəˈlæntə/

Attributes

Atalanta was usually depicted as a beautiful young maiden. She often carried her bow and arrows, with which she was famously skilled.

Family

Atalanta was the daughter of a king, though the name of the king and the location of his kingdom vary among the ancient sources. Atalanta’s father was sometimes said to have been the ruler of Arcadia, and sometimes a ruler of Boeotia.[2]

Atalanta eventually married a man named either Hippomenes or Melanion after he had proven himself by beating her in a footrace.[3] Atalanta had a son named Parthenopaeus who fought with the Seven against Thebes. In some traditions, Atalanta was the lover of Ares, and it was he (not her husband) who fathered Parthenopaeus.[4]

Mythology

Birth and Childhood

Atalanta’s father, a minor king, wanted a son; when he had a daughter instead, he left the infant to die by exposing her in the wilderness. Atalanta was subsequently suckled by a she-bear. She grew up in the woods and mountains and became a skilled hunter.

As a young woman, she made a vow to the goddess Artemis that she would remain a virgin. When two centaurs, Hylaeus and Rhoecus, tried to force themselves upon her, she killed them using her bow.

Adventures

As an adult, Atalanta participated in several famous exploits alongside the male heroes of her time. According to some sources, she was among the Argonauts who sailed with Jason to steal the Golden Fleece.[5]

In one myth, sometimes represented in ancient art, Atalanta wrestled with the hero Peleus during the funeral games of King Pelias of Iolcus. Peleus, the father of the mighty Achilles, was an Argonaut and a great warrior in his own right; but Atalanta defeated him in their wrestling match.

Vase painting of Atalanta wrestling Peleus, Chalcidian hydria (540–530 BCE).

Bibi Saint-PolCC BY-SA 3.0Atalanta also took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt, though with tragic consequences. The Calydonian Boar was a monstrous creature sent to wreak havoc on Calydon after the city’s king, Oeneus, offended the goddess Artemis. All the greatest heroes of Greece, including Atalanta, came to Calydon to help hunt down the terrible boar. They were led by Meleager, the brave son of King Oeneus.

During the hunt, several men were killed by the boar. Atalanta eventually managed to hit the animal and was the first to draw blood from it; soon after, Meleager killed it. But Meleager had fallen in love with the beautiful Atalanta and offered her the boar’s skin, claiming she had earned it because she had been the first to wound the beast. This angered Meleager’s uncles, and they tried to take the hide from Atalanta. In revenge, Meleager killed them.

In the ensuing struggle, Meleager was ultimately killed too. The best-known version of the myth states that Meleager’s mother, Althaea, heartbroken at hearing that Meleager had killed her brothers, threw a magical log into the fire that consumed Meleager’s life as it burned.

Atalanta and Meleager by Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1616).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Footrace

After many years, Atalanta was reunited with her father. Still hoping for a male heir, he insisted that his daughter be married. Atalanta said she would only marry the man who could beat her in a footrace. Some sources claimed that any suitor who lost would be put to death.

After many suitors had tried and failed to win Atalanta’s hand, one young man (called either Hippomenes or Melanion, depending on the source) convinced Aphrodite to come to his aid. Aphrodite gave the young man three golden apples and told him to drop them at intervals during the footrace.

Hippomenes and Atalanta by Guido Reni (1618–1619).

Prado MuseumPublic DomainThe young man did as he was told: every time Atalanta started gaining on him, he dropped an apple, and she would stop to pick it up. This slowed her enough for the young man to win the race, and the virgin Atalanta finally married. She had a son, Parthenopaeus, who would later fight in the war of the Seven against Thebes.

Metamorphosis

Atalanta and her husband eventually offended one of the gods by making love in their temple; as punishment, they were transformed into lions. Some ancient sources suggested that it was Aphrodite who caused them to commit this sacrilege to punish Atalanta’s husband for failing to properly honor her after she helped him win Atalanta.

Pop Culture

Atalanta has featured in some modern adaptations of the Greek myths, though she is rarely a central character. Atalanta has been depicted in the television show Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (1995–1999) and in the Hallmark miniseries Jason and the Argonauts (2000). She fights alongside Hercules in the 2018 film Hercules, based on the Radical Comics graphic novel Hercules: The Thracian Wars.

Atalanta has appeared in several novels, too, such as Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast (2003) by Robert J. Harris and Jane Yolen and Outrun the Wind (2018) by Elizabeth Tammi.

Atalanta is featured in several video games, including the Golden Sun series, Herc’s Adventures (an expansion of Zeus: Master of Olympus), Rise of the Argonauts, and Age of Mythology.