Andromeda

Perseus and Andromeda by Titian (ca. 1554–6).

The Wallace CollectionPublic DomainOverview

Andromeda was the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, the king and queen of mythical Ethiopia. Andromeda and her mother Cassiopeia were renowned for their beauty; but Cassiopeia’s excessive boasting soon angered the gods. As atonement, Cepheus and Cassiopeia were ordered to present Andromeda as a sacrifice to Poseidon’s sea monster.

Chained to a rock and left on the seashore, Andromeda would have been killed had it not been for Perseus, the slayer of Medusa, who passed by at just the right moment. In return for saving Andromeda, he was awarded the princess’s hand in marriage. Together, Perseus and Andromeda traveled to Greece and began the powerful Perseid dynasty.

Etymology

The name “Andromeda” (Greek Ἀνδρομέδα, translit. Andromeda) is a compound of two Greek words: anēr, meaning “man,” and medō, meaning “rule over.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Andromeda Ἀνδρομέδα (translit. Andromeda) Phonetic

IPA

[an-DROM-i-duh] /ænˈdrɒm ɪ də/

Attributes, Ethnicity, and Iconography

Andromeda was known for her remarkable beauty. As she was a princess of Ethiopia, it is reasonable to assume that she was black; indeed, it seems that ancient authors took it for granted that the mythical Ethiopians had dark skin.[1]

Yet the question of Andromeda’s ethnicity is more complicated. First, the exact location of mythical Ethiopia is unclear. In the Odyssey, Homer says that the Ethiopians “dwell sundered in twain, the farthermost of men, some where Hyperion [i.e., the sun] sets and some where he rises.”[2] Some later sources—for example, the fifth-century BCE historian Herodotus—identified Ethiopia with the ancient Kingdom of Kush, just south of Egypt, and therefore viewed the Ethiopians as black Africans.[3] Others, however, located Ethiopia near India in the east—close to where the sun rises every day.[4]

To complicate matters further, another tradition had emerged by the first century BCE that identified the site of Andromeda’s binding and rescue as Jaffa (also called Joppa, Iope, and Yaffo), a port city that is now part of Tel Aviv, Israel.[5] In this case, Andromeda and her parents would have been ethnically Phoenician, rather than black Africans.

As a result, some ancient authors described Andromeda as black[6] while others imagined her as white.[7] In ancient art, likewise, Andromeda could be depicted as either black or white.[8]

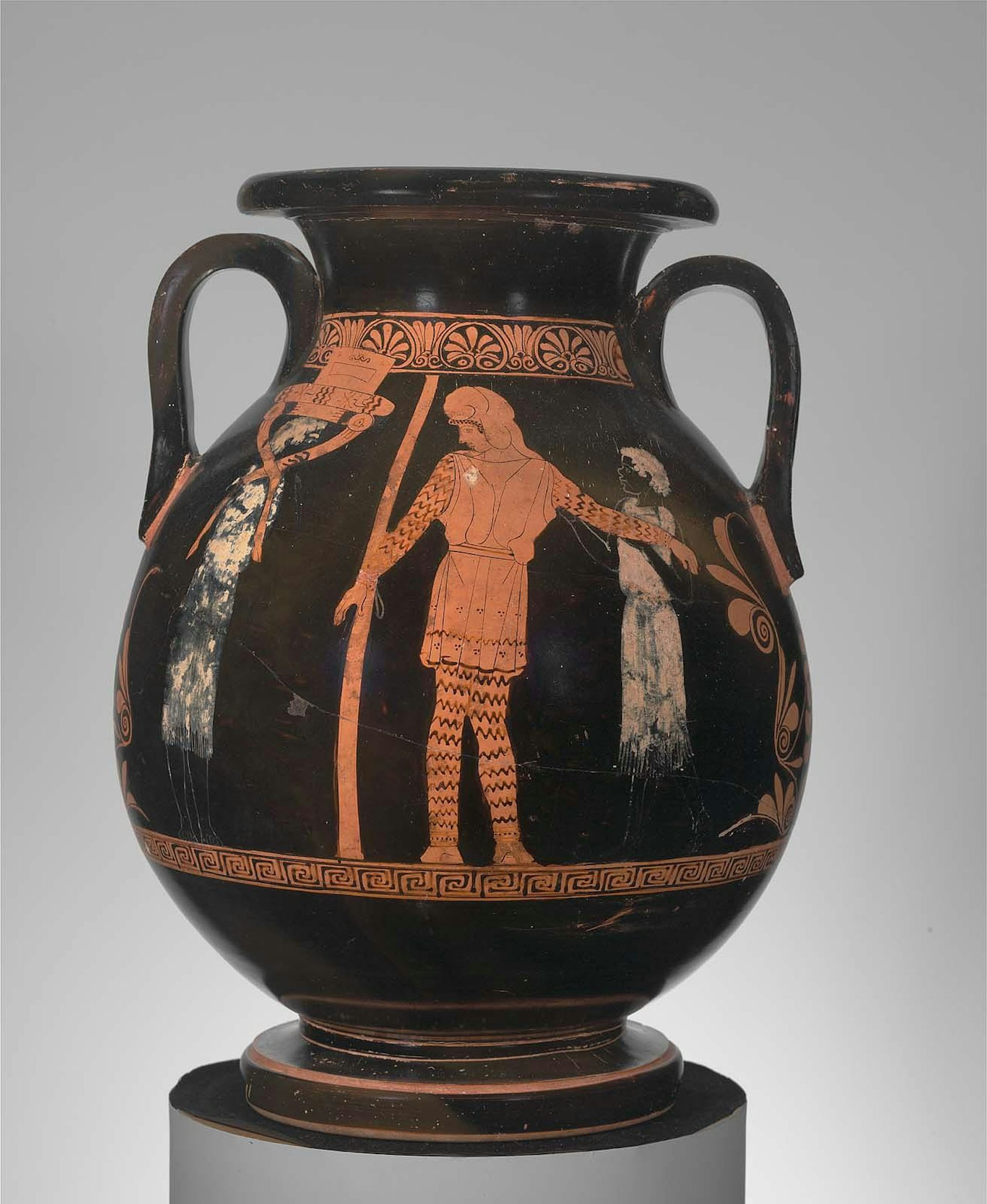

Red-figure pelike showing the binding of Andromeda, attributed to the workshop of the Niobid Painter (ca. 450–440 BCE). Though the Ethiopian slaves binding Andromeda are represented as black, Andromeda herself has the light-skinned complexion of a European (though she is outfitted in clothing which, from a Greek perspective, would have been regarded as distinctly foreign).

Museum of Fine Arts, BostonPublic Domain

Mosaic discovered at the "House of Poseidon" in Zeugma, Turkey showing Perseus with a darker-skinned Andromeda (2nd or 3rd century CE). Zeugma Mosaic Museum, Gazientep, Turkey.

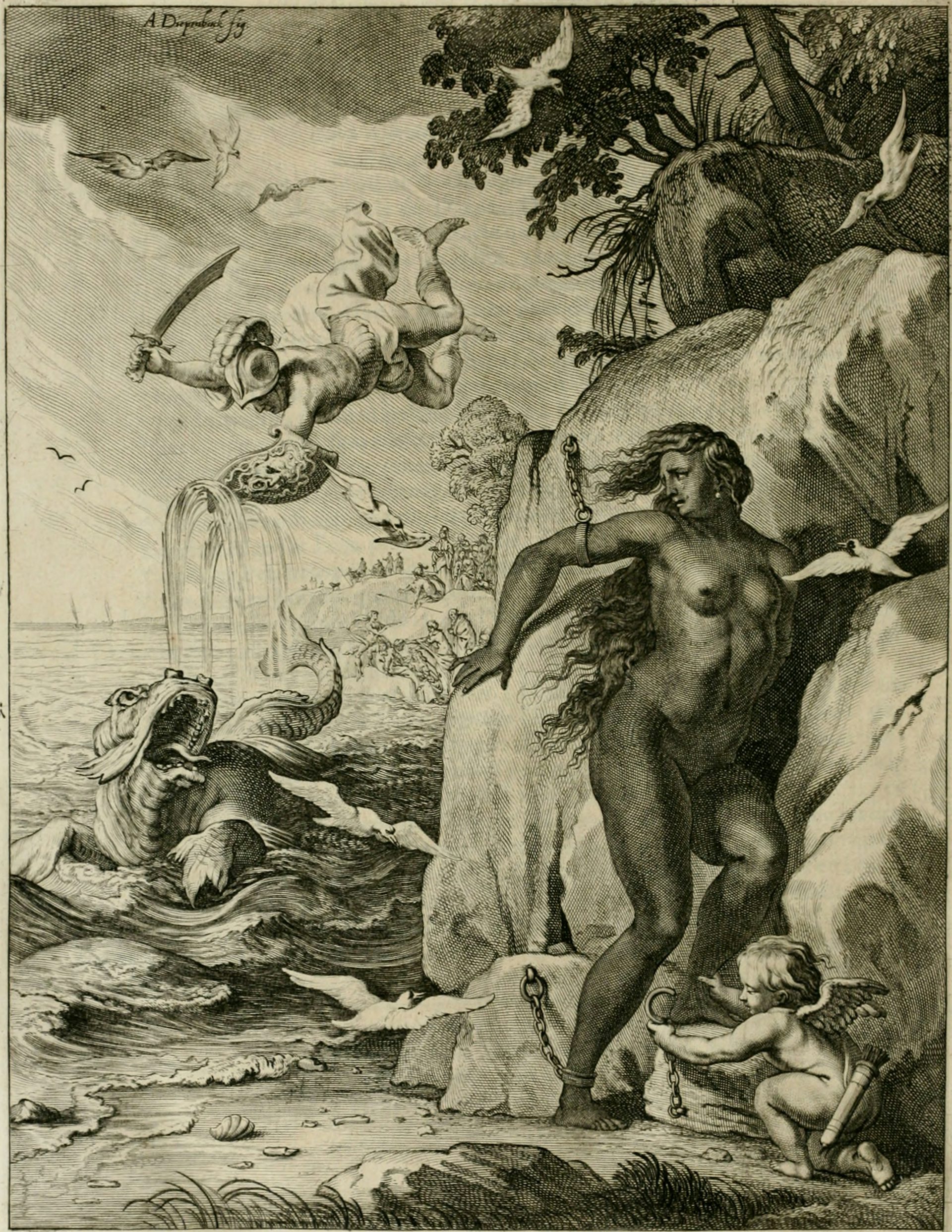

DossemanCC BY-SA 4.0Over the centuries, however, it became standard to portray Andromeda as white. There are a few exceptions—for example, Abraham van Diepenbeeck’s The Rescue of Andromeda—but most European artists who painted the scene of her captivity (including Rembrandt, Rubens, Poynter, and Doré) represented her with light skin. The same trend can be detected in other media: in the 1981 film Clash of the Titans, for example, Andromeda is played by white actress Judi Bowker.[9]

Engraving after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, The Rescue of Andromeda (1632–1635), from M. de Marolles, Tableaux du Temple des Muses (Paris: Nicolas L'Anglois, 1655).

Flickr CommonsPublic DomainFamily

Andromeda was the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, the king and queen of Ethiopia. After Perseus rescued Andromeda from Poseidon’s sea monster, the two were married. Sources vary on how many children they had. According to the most common tradition, they had six sons (Perses, Alcaeus, Sthenelus, Heleus, Mestor, and Electryon) and one daughter (Gorgophone).[10] But other traditions also included among their children two sons named Aelius and Cynurus[11] and a daughter named Autochthe.[12]

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

- Cepheus

Consorts

Husband

Children

Daughters

Sons

- Gorgophone

- Autochthe

- Perses

- Alcaeus

- Heleus/Aelius

- Mestor

- Sthenelus

- Electryon

- Cynurus

Mythology

Perseus

Andromeda was born to Cepheus and Cassiopeia, the king and queen of Ethiopia (or, according to some sources, of Jaffa in modern Israel; see above). Andromeda and her mother Cassiopeia were blessed with remarkable beauty. But this beauty would prove their undoing. In a moment of unforgivable hubris, Cassiopeia boasted that she (or Andromeda—there are different versions)[13] was more beautiful than the Nereids, the daughters of the sea god Nereus.[14]

This angered Poseidon, the supreme god of the sea. To punish Cassiopeia, Poseidon sent a sea monster (named Cetus in some sources) to ravage the shore of her and her husband’s kingdom. Cepheus eventually learned that the only way to get rid of the monster was to sacrifice his daughter Andromeda to it. Thus, Andromeda was bound to a great rock on the shore and left to die.

As Andromeda was awaiting her fate, Perseus happened to pass by on his way home from killing the Gorgon Medusa. When he learned what was happening—that the beautiful girl bound to the rock was to be sacrificed to Poseidon’s sea monster—Perseus made Cepheus and Cassiopeia an offer: if they promised him Andromeda’s hand in marriage, he would save her life. Cepheus and Cassiopeia agreed (apparently not considering that killing the sea monster might further anger Poseidon).[15]

Andromeda and the Sea Monster by Domenico Guidi (1694).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainPerseus was still armed with the divine weapons the gods had given him for his battle with Medusa: a helmet of invisibility, an adamantine sword, and winged sandals. He also had the head of Medusa, which turned all those who looked upon it to stone. With this arsenal he was able to kill the sea monster and rescue Andromeda.

The wedding ceremony of Perseus and Andromeda was interrupted, however, by Phineus, Andromeda’s former fiancé. A struggle ensued, in which Perseus ended up killing Phineus and his companions. In the wake of this carnage, Perseus and Andromeda left Ethiopia.

Greece and the House of Perseus

Andromeda followed Perseus back to Greece. The newlyweds stopped first on the island of Seriphos, where Perseus had been raised, so that he could save his mother Danae from the unwanted advances of King Polydectes. Perseus then took Andromeda to his ancestral kingdom of Argos on the Greek mainland.

Perseus and Andromeda by Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1622). Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAfter Perseus accidentally killed his father Acrisius (as an old prophecy had predicted he would), he gave up the throne of Argos—though he didn’t abandon royal life altogether. Instead, he became the king of Tiryns and Mycenae and made Andromeda his queen.[16] Together, Perseus and Andromeda had many important children and began the Perseid dynasty, or “House of Perseus.” Among their famous descendants was Heracles, perhaps the greatest hero of Greek mythology.

Constellation

After her death, Andromeda was transformed into a constellation, along with the other characters of her myth (Perseus, Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Cetus, etc.).[17] The Andromeda constellation contains the Andromeda Galaxy, the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way.

Pop Culture

Andromeda has appeared in several modern adaptations of the Perseus myth, including the 1981 film Clash of the Titans and its 2010 remake.

Andromeda has also given her name to various fictional characters and entities, among them the protagonist of Jodi Picoult’s novel My Sister’s Keeper (2004), the Harry Potter character Andromeda Tonks, Michael Chrichton’s novel The Andromeda Strain (1969), and a ship called the Princess Andromeda in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series.