Alcestis (Play)

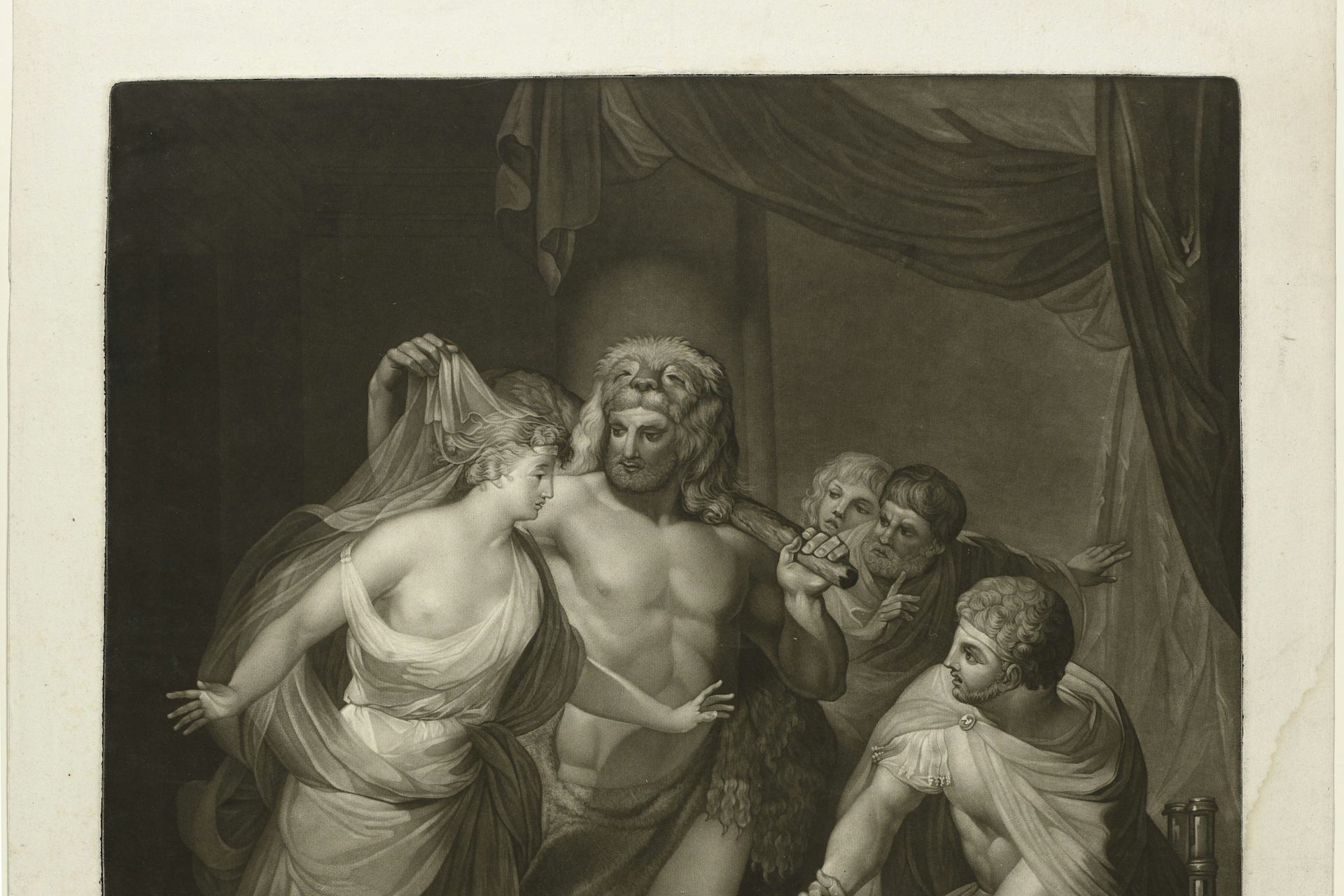

Hercules Brings Alcestis back from the Underworld by Joseph Spiegl, after Anton Wolff (1795)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainOverview

The Alcestis is a Greek tragedy by Euripides, and the earliest of his surviving plays. It was originally produced in 438 BCE at the City Dionysia, an annual dramatic festival in which playwrights would compete to entertain the citizens of Athens. The tetralogy with which it was performed won second place at the Dionysia.

Though the Alcestis is formally a tragedy, exhibiting tragic diction, themes, and conventions, it was performed last in its tetralogy, in the place typically reserved for a satyr play.[1] Because of this, scholars have sometimes viewed the Alcestis as a quasi-satyr play rather than a true tragedy.

Euripides’ Alcestis tells the story of the noble Alcestis, who voluntarily gave her life to save her husband Admetus. Though the play clearly describes her death and funeral, it ends with Heracles restoring a veiled woman to Admetus, who is revealed to be Alcestis. Heracles claims to have wrestled her away from Thanatos, the personification of death.

Title

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Alcestis Ἄλκηστις (Álkēstis) Phonetic

IPA

[al-SES-tis] /ælˈsɛs tɪs/

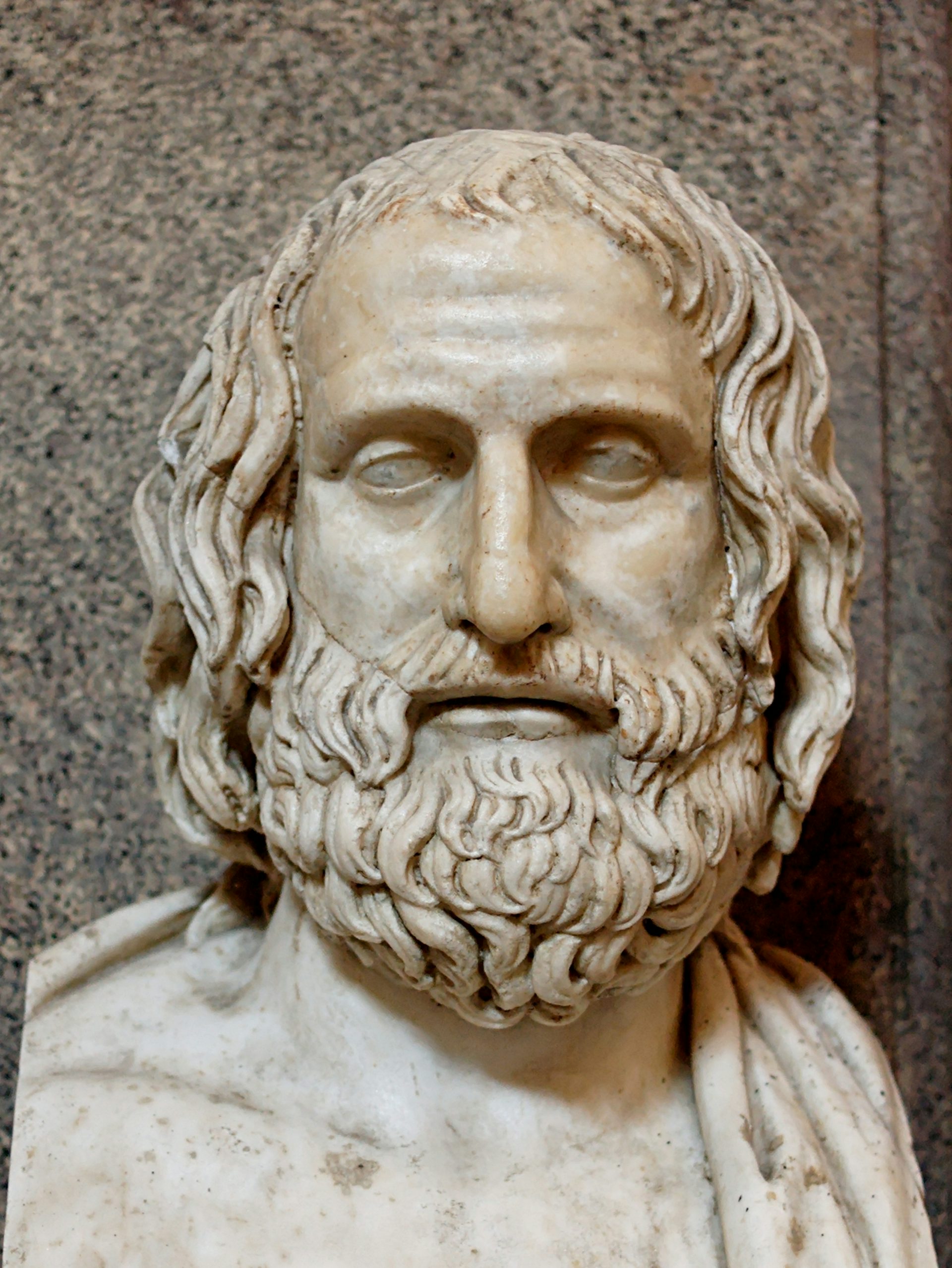

Author

Euripides, the author of the Alcestis, was an Athenian tragedian who is thought to have lived from around 480 BCE to 406 BCE. He was the youngest of the three canonical Athenian tragedians (the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles) and was known for exploring avant-garde, subversive, and innovative themes.

Roman bust of Euripides after a Greek original from ca. 330 BCE

Vatican Museums, Vatican / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainOver the course of his career, Euripides composed some ninety plays, eighteen of which survive in full.[2] Despite his formidable output—we have more plays by Euripides than by Aeschylus and Sophocles combined—Euripides won only four victories at the annual Dionysia competition during his lifetime (with a fifth awarded the year after his death). Yet Euripides’ popularity and literary influence have continued to grow, and some now regard him as the greatest of the Athenian tragedians.

Little is known about Euripides’ personal life; most ancient testimonia and biographies read more like fable than fact. Euripides seems to have been born on Salamis, an island near Athens, to a family of hereditary priests. He was married twice, both times unhappily, and had three sons. Ancient sources claimed that Euripides was a recluse and may have even lived alone in a cave in Salamis, though the veracity of such stories is obviously dubious. He died in 406 BCE at the court of the Macedonian king Archelaus.

Throughout his lifetime—and after his death, too—Euripides had a reputation as a challenging and controversial playwright. The comedian Aristophanes, one of his contemporaries, often mocked Euripides as an impious snob. In time, however, Euripides came to be recognized for his capable exploration of emotional realism, his innovative treatment of traditional mythology, and his persistent questioning of contemporary values.

Mythological Context

The story of Alcestis and Admetus was known long before Euripides composed his play in the fifth century BCE. In Homer’s Iliad, for example—written in the eighth century BCE, but based on even older oral traditions—Alcestis is described as “queenly among women” and the “comeliest of the daughters of Pelias.”[3] The myth of Alcestis was also staged by the tragedian Phrynichus, who lived a generation before Euripides, though Phrynichus’ Alcestis unfortunately has not survived.

Despite these literary predecessors, it was Euripides’ Alcestis that ultimately became the most important account of Alcestis’ self-sacrifice. Indeed, Euripides seems to have popularized the myth, as representations of Alcestis in the visual arts became considerably more common soon after the play was performed in 438 BCE.[4]

The basic story of Alcestis and Admetus—known from Euripides’ play, as well as from allusions and summaries in other ancient texts—tells of how Admetus, the king of Pherae, was granted the chance to escape death if he could find someone to voluntarily die in his place. This remarkable gift came from Apollo, who loved Admetus for treating him well when the god was forced to serve him as a slave (in one tradition, Admetus and Apollo were even lovers).

How Apollo won this boon for his mortal favorite is unclear. In Euripides’ Alcestis, Apollo states that he tricked the Moirae (the “Fates”), the goddesses responsible for allotting the length of each human being’s life.[5] Aeschylus, alluding to the myth in his Eumenides, reports that Apollo accomplished this trick by getting the Moirae drunk.[6] Whatever the details, all accounts seem to agree that only Alcestis, Admetus’ wife, was willing to die in his place.

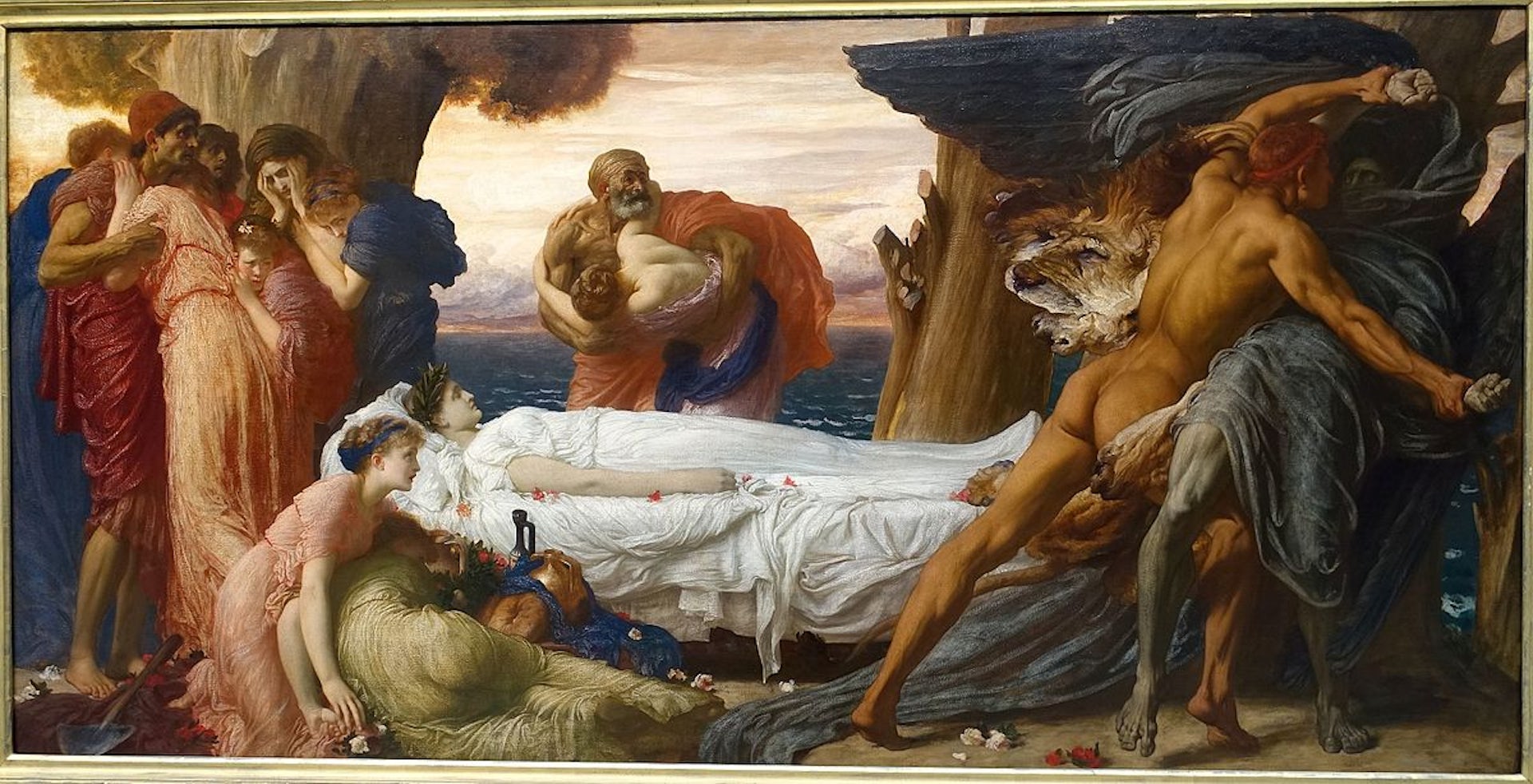

Euripides’ Alcestis offers a poignant depiction of Alcestis’ death and burial. As Admetus and his household mourn for her, the hero Heracles stops at Pherae en route to one of his Twelve Labors. Not wishing to dampen his friend’s mood, Admetus conceals the death of his wife, but Heracles eventually learns of what happened. Determined to repay Admetus’ generous hospitality, Heracles visits Alcestis’ tomb and wrestles her from the very hands of Death (the personification Thanatos).

Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis by Frederic Lord Leighton (ca. 1869–1871)

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT / DaderotPublic DomainThough this was certainly the most familiar version of the Alcestis myth,[7] it was not the only one circulating in antiquity.[8] In one tradition, for example, it was Persephone, the goddess of the Underworld, who sent Alcestis back to the land of the living because she took pity on her or admired her wifely virtue.[9] But due to Euripides’ popularity, his play established the most dominant and influential form of the myth.

Characters

The following is a list of characters from Euripides’ Alcestis, in order of appearance:

Apollo (god of the arts, prophecy, and healing)

Thanatos (“Death” personified)

Chorus (elders of Pherae)

Maidservant

Alcestis (queen of Pherae; wife of Admetus)

Admetus (king of Pherae; husband of Alcestis)

Heracles (Greek hero; friend of Admetus)

Pheres (father of Admetus)

Slave

Synopsis

The play begins with a prologue in which Apollo tells the audience of his history with Admetus, who treated him well when he was forced by Zeus to serve Admetus as a slave. In gratitude for this piety and kindness, Apollo has convinced the Moirae to allow Admetus to escape his fated death—but only if he can find someone to voluntarily die in his place. Only Alcestis, Admetus’ wife, will agree to this.

Thanatos, the divine personification of death, enters and explains that he has come to claim Alcestis. Apollo fails to convince Thanatos to spare the poor woman, but before he departs, Apollo hints that Heracles will ultimately take Alcestis from Thanatos by force.

As Apollo and Thanatos exit, the Chorus, made up of men from Pherae, arrives on stage. They sing their first choral song, the parodos, and learn of Alcestis’ preparations for her imminent death. The Chorus asks Zeus and Apollo to rescue Alcestis, though they know it is already too late.

Alcestis enters, supported by servants and followed by Admetus and their two children. She is dying. Admetus is overcome by grief and promises Alcestis he will never remarry. After asking Admetus to honor her and treat their children justly, Alcestis says a final goodbye to her family and dies. One of the children delivers a brief lament, after which Admetus imposes a year of mourning on his kingdom of Pherae. The Chorus, left alone on stage, wishes their beloved queen a blessed afterlife and predicts that poets will lavishly praise her virtues.

At the conclusion of the Chorus’s song, Heracles arrives at the palace. He explains to the Chorus that he is on his way to Thrace to steal the mares of Diomedes (one of the famous Twelve Labors assigned to him by Eurystheus). Admetus greets Heracles warmly and insists that he stay with him as a guest. Not wanting to trouble the great hero, Admetus conceals Alcestis’ death from Heracles, despite the Chorus’s misgivings.

Following another choral song, Admetus enters to prepare his wife’s funeral procession. His father Pheres arrives with funerary gifts, and he and Admetus fight bitterly with each other. Both men accuse the other of being responsible for Alcestis’ death by clinging shamelessly to life. Admetus ultimately disowns his father and sets off with the Chorus to bury Alcestis.

Meanwhile, Heracles learns from one of Admetus’ slaves that Alcestis has died and resolves to rescue her in order to repay Admetus for his hospitality. Heracles sets off just as Admetus and the Chorus return. As Admetus mourns the loss of his wife, the Chorus sings of the power of the goddess Ananke (“Necessity”).

In the last scene (the exodos), Heracles returns with a veiled woman who is ultimately revealed to be Alcestis. He reports that he found Thanatos near Alcestis’ tomb and proceeded to fight him for the noble queen. Admetus thanks Heracles and the gods for his good fortune and enters his home, his wife once more by his side.

Marble sarcophagus decorated with scenes from the myth of Admetus and Alcestis (161–170 CE)

JastrowPublic DomainStyle and Composition

The first performance of the Alcestis is dated to 438 BCE, making it the earliest of Euripides’ surviving plays. It was performed at the City Dionysia competition as part of a tetralogy, along with the tragedies Cretan Women, Alcmaeon in Psophis, and Telephus (all of which are now lost).

Strangely, as the fourth play of its tetralogy, the Alcestis occupied the spot usually reserved for a satyr play. Yet the Alcestis is clearly a tragedy, employing the diction, structure, and themes of the genre and lacking most of the basic stylistic features of satyr plays (such as explicit sexual themes and a chorus of satyrs). At the same time, some of the themes and motifs developed by the playwright, such as the drunkenness of Heracles, are reminiscent of satyr plays. The Alcestis thus challenges conventional genre classifications, leading scholars to number it among the most puzzling of Euripides’ so-called “problem plays.”

Admittedly, some of the text’s genre problems are actually quite minor: for instance, the Alcestis is not any less of a tragedy for using humor or concluding (at least ostensibly) with a happy ending, as such features can be found in a number of Attic tragedies. Nonetheless, the combination of its unusual performative context, its questioning of traditional values, and its pervasive ambiguity make it a difficult work to classify and interpret.

Themes

At its core, the Alcestis is a play about human beings’ desire for life in the face of the inevitability of death. The plot is centered on Admetus’ attempt to avoid death by allowing his wife Alcestis to perish in his place. This premise juxtaposes two ideas: 1) that death can be postponed, and 2) that it is also inevitable. In developing these ideas, the play raises serious questions about how far we should go to extend our lives, whether it is right to ask others to die for us, and whether life can ever be long enough.

The play also explores the themes of human virtue and piety. From the very first lines, Admetus is introduced as a righteous man; indeed, it is because of this righteousness that Apollo grants him the chance to escape death. Admetus is certainly preoccupied with his reputation for generosity and kindness, as demonstrated by his insistence on showing hospitality to Heracles even while he is mourning his wife.

Yet many scholars and critics have questioned Admetus’ supposed virtue: was it right for Admetus to ask his loved ones to die for him? Even some of his seemingly virtuous actions can be deemed inappropriate. Notably, by entertaining Heracles, Admetus breaks the promise he made Alcestis to ban all revelry and music from his home after she died (to say nothing of the lies he tells Heracles in the process, or even the basic respect his actions deny the dead Alcestis).

Alcestis, like Admetus, is concerned with her reputation: she is well aware that her sacrifice will win her undying fame. Throughout the play, Alcestis is universally hailed as a model of wifely virtue, especially by the Chorus. Even Pheres, who calls her foolish for dying for Admetus, admits that Alcestis is undeniably brave.

Like many Attic tragedies, the Alcestis is also interested in the relationship between gods and mortals. In the context of the play, many of the gods are depicted as quite human: Apollo, for example, is punished by his father for his impulsive anger, and Thanatos is physically bested by Heracles (who has not even been deified yet).

Yet the gods also belong to a world that is remote from humans, and they often exhibit a gross misunderstanding of mortals and their emotions. Indeed, Apollo’s “gift” to Admetus—which sets the play in motion—winds up causing great suffering, suggesting that the gods may harm mortals even when trying to help them. In fact, in the end it is not the god Apollo but the mortal Heracles who saves the day by restoring Alcestis to Admetus.

The play’s ambiguous themes culminate in an ending that is also ambiguous. In trying to help Admetus, Apollo actually brings out the worst in him. In sacrificing herself to save her husband, Alcestis also causes him and their household unbearable suffering. In trying to avoid his death, Admetus invokes a fate worse than death. And in trying to be a virtuous host, he breaks the promise he made his wife to lead a life of uninterrupted mourning.

Tondo of an Attic red-figure cup by the Brygos Painter showing Apollo (left) and his sister Artemis (right) (ca. 470 BCE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainIt is worth asking whether Admetus and Alcestis’ future life together can ever be happy, or whether Alcestis will realize that she agreed to sacrifice herself for a man who proved himself undeserving. The audience is even left wondering if the Alcestis of the final scene—who, significantly, does not say a word—is the real Alcestis at all. In the end, these ambiguities force the audience to wrestle with challenging ideas and work out their own interpretations.

Reception

The myth of Alcestis was not a popular subject for ancient tragedy. As a result, Euripides’ play was, from the beginning, the most important and widely known retelling. In the European Middle Ages, the story was adapted by writers such as Giovanni Boccaccio and Geoffrey Chaucer, who usually made Admetus more unambiguously noble by having Alcestis offer her life of her own volition, rather than Admetus asking her to do so.

In the eighteenth century, more and more translations of Euripides’ Alcestis began to circulate, exerting a discernible influence on European literature and culture. The play was adapted into numerous operas, for example, including ones by George Frideric Handel (1719) and Christoph Willibald Gluck (1767).

The Alcestis has also been adapted into more modern plays, many of which alter the setting, characters, and various features of the plot. For example, James Thomson’s Edward and Eleanora (1775) sets the story in Palestine during the Crusades; Francis Talfourd’s Alcestis, the Original Strong-Minded Woman (1850) is a burlesque of Euripides’ play; and T. S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party (1949) repurposes the story to explore the spiritual emptiness of contemporary life and marriage (rendering the original characters completely unrecognizable in the process). Another notable adaptation of the play is Robert Browning’s Balaustion’s Adventure (1871), which is part translation, part paraphrase, and part commentary on Euripides’ play.

Today, Euripides’ Alcestis and its many adaptations are still frequently performed.

Translations

Translations of the Alcestis are usually found in volumes of Euripides’ collected plays. The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Murray, Gilbert, trans. The Alcestis of Euripides. London: Allen and Unwin, 1915: Older translation in rhyming verse.

Dale, A. M., ed. and trans. Euripides: Alcestis. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1954: Accurate translation with an influential introduction.

Arrowsmith, William, trans. Euripides: Alcestis. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974: Readable verse translation.

Conacher, Desmond J., ed. and trans. Euripides: Alcestis. Classical Texts. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1988: An accurate translation with facing Greek text, keyed to a commentary suitable mainly for beginners.

Hughes, Ted, trans. Euripides’ Alcestis: A New Translation. London: Faber and Faber, 1999: Verse translation of the play by a well-known modern poet.

Kovacs, David, ed. and trans. Euripides: Cyclops, Alcestis, Medea. Loeb Classical Library 12. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001: An accurate prose translation with facing Greek text; can be viewed online through the Perseus Project.

Davie, John, trans. Medea and Other Plays. Edited by Richard B. Rutherford. London: Penguin, 2003: An accurate and idiomatic prose translation, best suited to more knowledgeable readers.

Parker, L. P. E., ed. and trans. Euripides: Alcestis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007: An accurate translation with facing Greek text, keyed to a commentary geared toward advanced readers.

Carson, Anne, trans. Grief Lessons: Four Plays by Euripides. New York: NYRB Classics, 2008: Contains verse translations of the Alcestis as well as the Heracles, Hecuba, and Hippolytus.

Waterfield, Robin, trans. Euripides: Heracles and Other Plays. Edited by James Morwood. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008: An accurate, clear, and idiomatic prose translation with thematic introductions.

Lattimore, Richmond, trans. Euripides I: Alcestis, Medea, The Children of Heracles, Hippolytus. 3rd ed. Edited by Mark Griffith and Glenn W. Most. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013: Readable and accurate verse translation with a basic introduction and notes.