Alcestis (daughter of Pelias)

Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Soul of Alcestis by Herbert Thomas Dicksee (1884).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOverview

Alcestis, the daughter of Pelias, was a Greek princess known for her beauty as well as her virtue. She was married to Admetus, the king of Pherae in the northern Greek region of Thessaly.

Alcestis proved herself a paragon of matrimonial devotion when it came time for Admetus to die. The god Apollo, who loved Admetus, devised a way for him to put off his fate: if Admetus could find someone to die in his place, then he could go on living. Only Alcestis was willing to accept these terms. After sacrificing herself for her husband, her selfless deed was rewarded and she was restored to life, either by the hero Heracles or, in other versions, by Persephone, the queen of the Underworld.

Etymology

The name “Alcestis” (Greek Ἄλκηστις, translit. Alkēstis) was most likely derived from the Greek word alkē, meaning “defense, help, strength,” or from the underlying Indo-European root *h₂elk-/*h₂lek-s- (“ward off, defend”). Alcestis’ name thus reflects her mythical role as the one who “defended” her husband from death.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Alcestis Ἄλκηστις (translit. Alkēstis) Phonetic

IPA

[al-SES-tis] /ælˈsɛs tɪs/

Titles and Epithets

Alcestis had a range of epithets that highlighted her virtue, including aristē, “greatest,” and kednē, “dutiful.”

Attributes and Iconography

Alcestis was well known for her beauty. In the Iliad, for example, Homer refers to her as the “comeliest of the daughters of Pelias.”[1] But Alcestis’ most important attribute—the one at the heart of her myth—was her virtuous and noble nature, which led her to willingly die for her husband Admetus.

Scenes from Alcestis’ myth, especially her return from the Underworld with Heracles, became more common in ancient art around the end of the fifth century BCE (after the myth was popularized by Euripides’ Alcestis of 438 BCE).[2]

Family

Alcestis was the daughter of Pelias—who ruled the kingdom of Iolcus on the eastern coast of northern Greece—and his wife, whose name was either Anaxibia,[3] Phylomache,[4] or Alphesiboea.[5] The mythographer Apollodorus lists her siblings as Acastus, Pisidice, Pelopia, and Hippothoe.[6]

Family Tree

Mythology

Marriage to Admetus

Admetus was one of the daughters of Pelias, the king of Iolcus in northern Greece. When she was of marriageable age, her beauty drew many suitors to her father’s kingdom. But Pelias announced that he would only marry his daughter to the man who could yoke a lion and a boar to a chariot.

One of Alcestis’ suitors was Admetus, the king of Pherae. Years before, the god Apollo had been forced to serve Admetus as a slave. But Admetus was a kind and respectful master, which earned him Apollo’s undying friendship. Being friends with one of the most powerful Olympian gods naturally had its benefits. When Admetus wished to marry Alcestis, Apollo helped him accomplish the seemingly impossible task of yoking a lion and a boar to a chariot, thus winning his mortal friend a bride.[9]

Apollo Herding the Cattle of Admetus by Moyses van Wtenbrouck (1600–1645).

RijksmuseumPublic DomainThe Vicarious Death of Alcestis

From the very beginning, the marriage of Admetus and Alcestis was plagued by ill omen. According to Apollodorus, Admetus offended Artemis by forgetting to offer her a sacrifice when he married Alcestis. Because of this, when Admetus entered his bedchamber on his wedding night, he found it full of coiled snakes. However, with the help of his old friend Apollo (who, incidentally, was also Artemis’ twin brother), Admetus managed to appease Artemis.[10]

This was only the beginning of Admetus and Alcestis’ troubles, however. Shortly after the wedding—the exact timing varies by the source—Admetus learned that he was fated to die soon. But Apollo again came to the rescue, bringing Admetus an unprecedented but problematic favor from the Moirae (the Greek goddesses of fate): Admetus could live on, but only if he found another mortal to voluntarily die in his place.

Alcestis, the symbol of the dutiful Greek wife, was the only one who offered to die for Admetus. With the bargain struck, Thanatos, the personification of death, carried her off to the Underworld.

But Alcestis did not stay in the Underworld for long. In some versions, Heracles (another one of Admetus’ powerful friends) wrestled Alcestis back from Thanatos.[11] In other versions, Persephone, the queen of the Underworld, took pity on Alcestis and sent her back to the land of the living.[12]

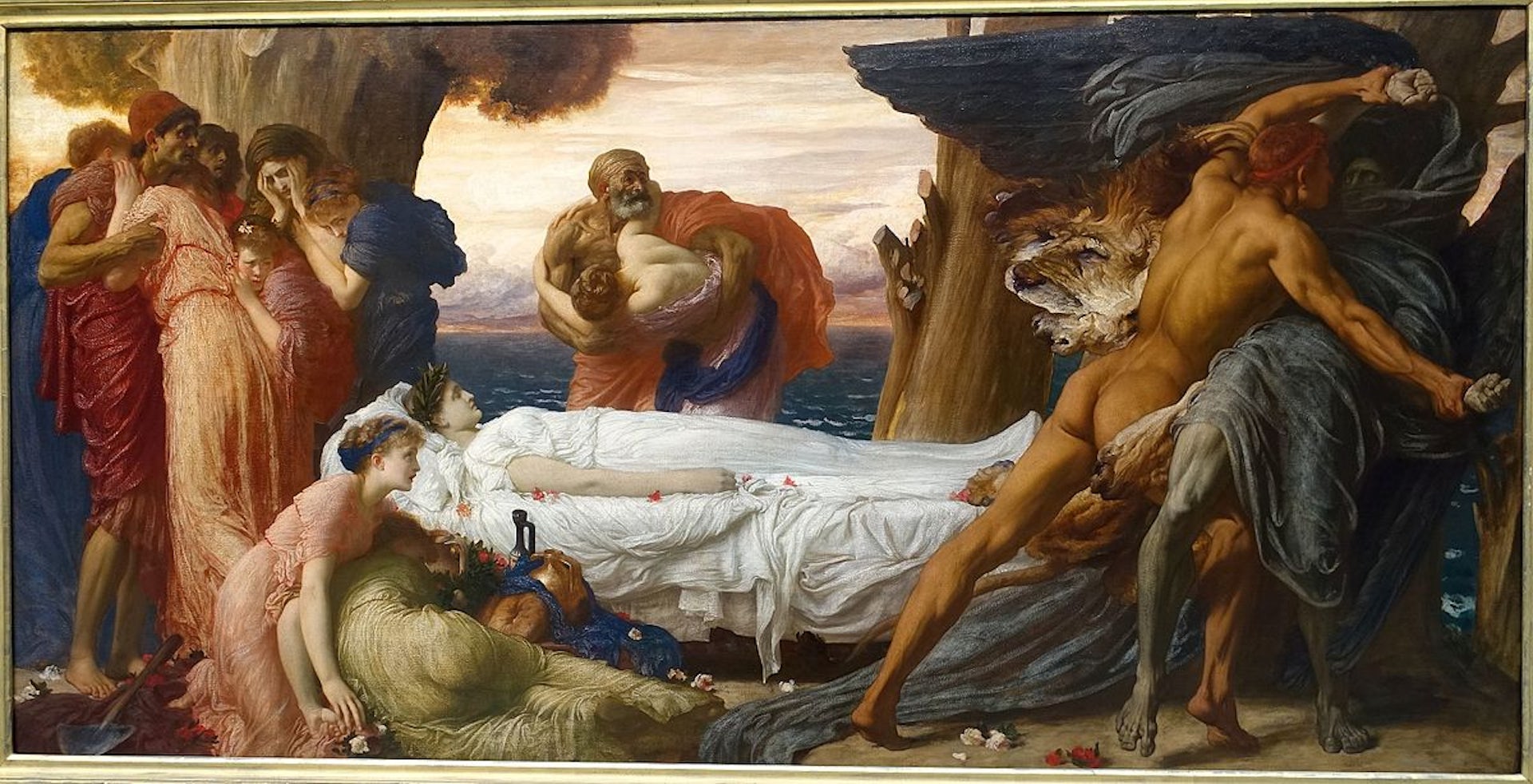

Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis by Frederic Lord Leighton (ca. 1869–1871). Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT.

DaderotPublic DomainPop Culture

The myth of Alcestis remains well known. She has inspired numerous poems, operas, plays, and ballets, including works by Rainer Maria Rilke, George Handel, Louise Talma, H. P. Lovecraft, and Sonia Greene.