Agamemnon (Play)

Clytemnestra Hesitates before Killing the Sleeping Agamemnon by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1817)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainOverview

The Agamemnon is an Attic tragedy by Aeschylus, one of the three canonical tragedians of classical Athens. It was originally produced in 458 BCE for the City Dionysia, an annual dramatic festival in which playwrights would compete to entertain the citizens of Athens. The playdramatizes Clytemnestra’s murder of her husband Agamemnon after his return from the Trojan War.

The Agamemnon is the first play in the Oresteia, a trilogy of connected tragedies based on the murder of Agamemnon and the revenge later exacted by his son Orestes. With its themes of retribution, justice, fate, and suffering, it remains one of the best-known Attic tragedies.

Title

The Agamemnon (Greek Ἀγαμέμνων, translit. Agamémnōn) is named for the play’s protagonist, a king and warrior who conquered Troy before being murdered by his wife Clytemnestra.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Agamemnon Ἀγαμέμνων (Agamémnōn) Phonetic

IPA

[ag-uh-MEM-non] /ˌæg əˈmɛm nɒn/

Author

Aeschylus (ca. 525/4–456/5 BCE) was the oldest of the three canonical Attic tragedians (the other two being Sophocles and Euripides). Regarded as the “father of tragedy,” Aeschylus introduced important innovations to the genre and was highly esteemed for his dextrous use of symbolism and metaphor, as well as his exploration of justice and the role of the gods in human life.

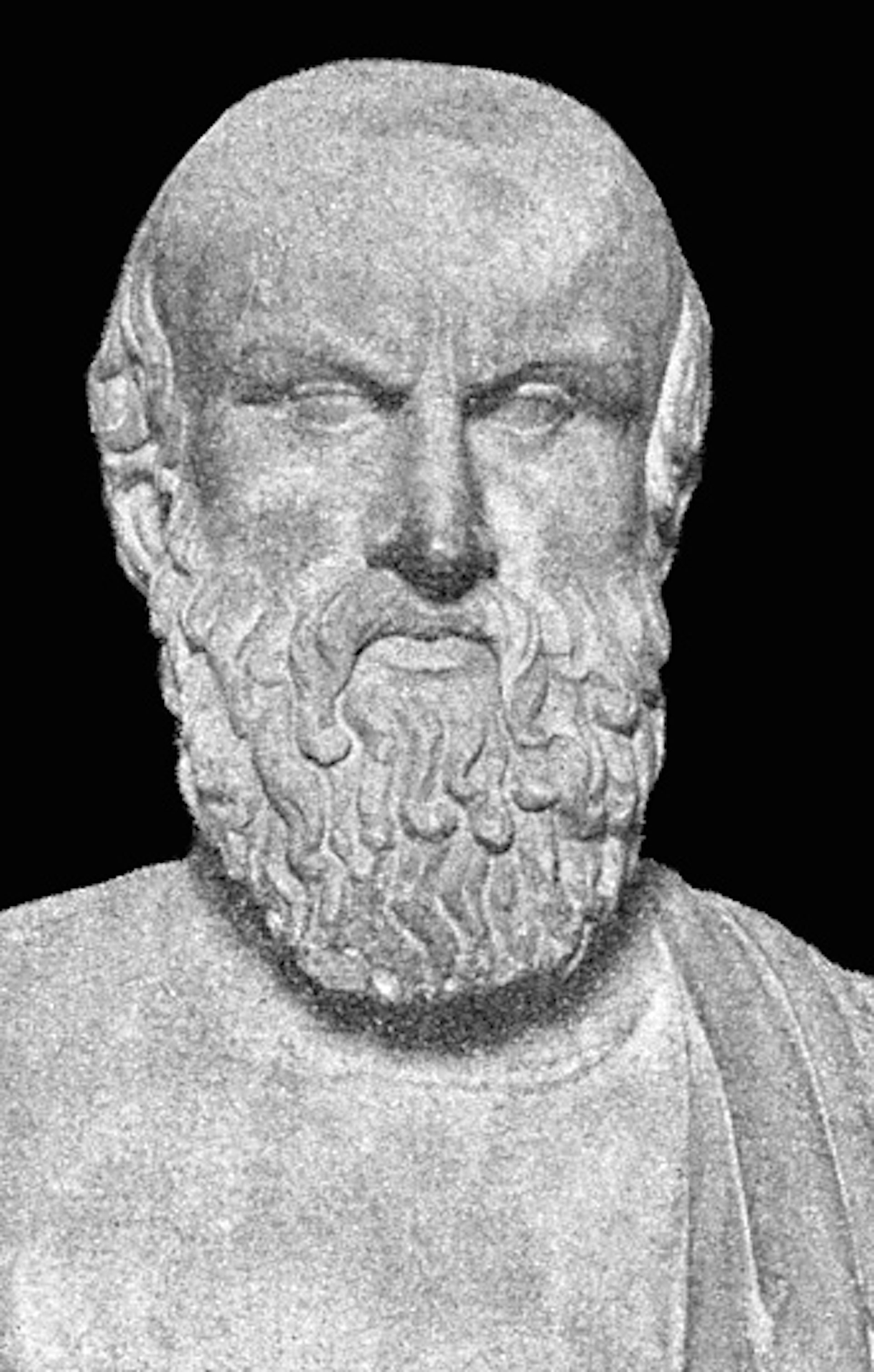

A herm, conventionally said to be a bust of Aeschylus (first century CE)

Capitoline Museums, RomePublic DomainFrom the many legends surrounding Aeschylus’ life, we can extract a few details that are probably factual. Aeschylus was born to an aristocratic family from Eleusis (or thereabouts). He began producing tragedies in the 490s BCE, winning his first victory at the Dionysia in 484 BCE. He fought against the Persians at Marathon in 490 BCE and at Salamis in 480 BCE. Around 470 BCE, he visited Sicily at the invitation of the Syracusan tyrant Hieron; he later returned to Sicily and ultimately died there.

Over the course of his distinguished career, Aeschylus composed some ninety plays and won thirteen victories at the Dionysia. He was revered both during his life and after, though by the fourth century BCE his plays were increasingly seen as archaic, especially compared to the works of Sophocles and Euripides.

Mythological Context

The myth of Agamemnon’s murder is attested from the earliest periods of Greek literature. References to the myth are woven into Homer’s Odyssey, for example: Agamemnon’s disastrous return from Troy is used as a foil for Odysseus’ difficult but ultimately successful return to Ithaca. The dead Agamemnon himself appears twice in the Odyssey (as a shade in the Underworld).

Homer’s treatment of Agamemnon’s downfall primarily focuses on Clytemnestra’s adultery (which is juxtaposed with the fidelity of Odysseus’ wife Penelope). Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, on the other hand, draws on a much broader mythical history of violence and revenge, which haunted Agamemnon’s family for generations.

The story behind the Agamemnon begins with Atreus and Thyestes, the two sons of Pelops. Banished from their homeland in the region of Elis, Atreus and Thyestes immigrated east, where they quarreled over the throne of Mycenae.[1] The brothers’ rivalry led to increasingly troubling acts of violence and betrayal, the most infamous of which came when Atreus cooked Thyestes’ sons and served them to him at a feast. When Thyestes discovered what his brother had done, he cursed him—what became known as the “Curse of Atreus.”

Thyestes, with the help of his surviving son Aegisthus, eventually murdered Atreus. Atreus’ sons Agamemnon and Menelaus—often known collectively as the Atreids or Atreidae—soon struck back, killing Thyestes and exiling Aegisthus. Agamemnon became king of Mycenae (or Argos, in Aeschylus’ version) and married the Spartan princess Clytemnestra. Menelaus married Clytemnestra’s sister Helen and succeeded her father as king of Sparta.

Years later, when the Trojan prince Paris ran off with Helen, Agamemnon and Menelaus raised a formidable Greek army to sail to Troy and win her back. Before they could sail, however, Agamemnon was ordered to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia in exchange for a wind to blow his fleet to Troy.

Fourth-style fresco from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii showing the sacrifice of Iphigenia (ca. 60–79 CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0This terrible sacrifice—never explicitly mentioned in the Homeric epics, but documented in many other early works of literature—is integral to the plot of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. When Aeschylus’ Clytemnestra murders Agamemnon, she justifies her actions as righteous revenge for Agamemnon’s sacrifice of their daughter. In fact, Aeschylus may have been the first to introduce this as Clytemnestra’s motivation for the murder; earlier sources, such as Homer’s Odyssey, do not specify any motivation for Clytemnestra other than treachery and faithlessness.

Clytemnestra’s infidelity is a consistent feature of the Agamemnon myth. As the story goes, while Agamemnon was away fighting at Troy, Clytemnestra began an adulterous affair with Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin and sworn enemy. When Agamemnon returned victorious from Troy after ten years, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus murdered him together. Most ancient literary and artistic sources have Aegisthus do the killing; in Aeschylus’ play, though, it is Clytemnestra who carries out the deed.

This is where Aeschylus’ Agamemnon ends. But the rest of the myth (which unfolds across the two remaining plays of the Oresteia) tells of how Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, returned home to avenge his father. With the help of his sister Electra, Orestes kills Aegisthus as well as his own mother. He is pursued by the Erinyes (the “Furies”) for the crime of matricide but is ultimately purified and acquitted with the help of Apollo and Athena.

Characters

The following is a list of characters from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, in order of appearance:

Watchman

Chorus (elders of Argos)

Clytemnestra (queen of Argos; wife of Agamemnon)

Herald

Agamemnon (king of Argos; husband of Clytemnestra)

Cassandra (Trojan princess and seer)

Aegisthus (cousin of Agamemnon; lover of Clytemnestra)

Synopsis

The play is set in front of Agamemnon’s palace in Argos. In the prologue, the Watchman, stationed on the roof of the palace, sights the beacons signaling the fall of Troy. The Watchman rejoices and exits to announce the news to Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife.

The Chorus, made up of Argive elders, enters and performs their first choral ode (the parodos). They sing of how Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus sailed to Troy after the Trojan prince Paris ran off with Menelaus’ wife Helen; of how Agamemnon was commanded to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis; and of the justice of the gods.

Paris and Helen by Jacques-Louis David (1788)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainClytemnestra enters, initiating the first episode. She proclaims that Agamemnon has sacked Troy, and that his victory has been conveyed to her through the progress of the signal fires from the conquered city.

In the first stasimon,[2] the Chorus praises Zeus for helping the Greeks sack Troy. They condemn the corruption of Paris and Helen and mourn the deaths of so many Greeks.

The Herald enters ahead of Agamemnon. In the second episode, he describes the decade-long war with the Trojans and confirms that the Greeks have finally prevailed. Clytemnestra rejoices upon hearing this. The Herald then adds that a storm destroyed much of the Greek fleet as it set sail from Troy.

The Chorus sings the second stasimon, expressing their disapproval of Helen and her actions and asserting that the gods always punish transgressors.

The third episode opens with the arrival of Agamemnon in a chariot. He is accompanied by Cassandra, a Trojan princess and seer whom he has claimed as a prize. Clytemnestra urges Agamemnon to enter the palace by walking on crimson tapestries she has set out for him. Though Agamemnon is hesitant at first, he eventually complies.

Following the third stasimon—in which the Chorus again expresses their fear of imminent disaster—Clytemnestra reenters and asks Cassandra to come inside. Cassandra does not respond. Once Clytemnestra has left, however, Cassandra addresses the Chorus, singing of the crimes committed by the House of Atreus in the past and at Troy. She predicts that she and Agamemnon are about to be murdered.

When the Chorus is unable to understand her, Cassandra laments the curse placed on her by Apollo, who gave her the gift of prophecy but made it so that no one would believe her. Accepting that she cannot escape her fate, Cassandra enters the palace at last.

During a brief choral interlude, the Chorus’s apprehension mounts until Agamemnon’s cries are heard from inside the palace (offstage). The individual members of the Chorus break off to discuss the murder and debate how to respond.

The exodus begins with a triumphant entrance from Clytemnestra. Standing over the bodies of Agamemnon and Cassandra, she proclaims that she has killed her husband and his concubine—which she justifies as punishment for Agamemnon’s sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia. Aegisthus, accompanied by his bodyguards, also enters and adds his justification for aiding Clytemnestra: he cites the crimes of Agamemnon and Atreus against his own father Thyestes.

The Chorus is horrified, but Clytemnestra prevents violence from breaking out between them and Aegisthus. Clytemnestra and Aegisthus take control of Argos, and the Chorus is forced to submit.

Clytemnestra by John Collier (1882)

Guildhall Art Gallery, LondonPublic DomainStyle and Composition

The Agamemnon was first performed at the annual City Dionysia in 458 BCE. It served as the first play in a tetralogy that contained the Oresteia—a trilogy of connected tragedies about Agamemnon’s homecoming and its aftermath—and a satyr play titled Proteus. The tetralogy won first place in competition.

The Oresteia is remarkable for being the only tragic trilogy to survive intact from antiquity. Unfortunately, the Proteus—the satyr play that completed the tetralogy—is now known only from fragments.

The structure of the Oresteia reflects Aeschylus’ rather unique interest in producing connected trilogies (Aeschylus’ successors, Sophocles and Euripides, hardly ever composed these kinds of connected texts). Moreover, as the last of Aeschylus’ extant works (he died only a few years after the production of the Oresteia), the trilogy shows Aeschylus at his most mature.

The Agamemnon combines some common features of Aeschylus’ style with more innovative elements. For instance, the importance and involvement of the Chorus, the dense symbolism and imagery, and the preoccupation with themes such as justice and religion are all typical of Aeschylus; however, the Agamemnon is the first of his plays to feature a third actor.

An Audience in Athens During Agamemnon by Aeschylus by William Blake Richmond (1884)

Birmington Museum and Art Gallery, BirmingtonPublic DomainThemes

The themes explored in the Agamemnon are numerous and complex, comprising justice, retribution, fate, religion, and gender, among others. These themes are also picked up and developed by the other plays of the Oresteia.

At its core, the Agamemnon is a play about justice—or, more specifically, retributive justice. Within the context of the play, justice is a harsh thing, impossible to escape; those who do wrong are punished, and these punishments ultimately come from the gods. This theme pervades the entire play, with justice meted out to Paris and Helen, to Troy, to the Greeks who plunder Troy, and, ultimately, to Agamemnon.

Part and parcel of this vision of justice is the idea that wisdom—that is, knowledge of how to behave justly—comes from suffering and punishment for wrongdoing. Yet none of the characters in the Agamemnon ever attain this wisdom. Only Agamemnon’s son Orestes—who features in the subsequent plays of the Oresteia—comes to exemplify this ideal, becoming wiser through his suffering rather than simply perpetuating the cycle of violence and retribution.

Related to the theme of justice is the concept of fate—in particular, the inescapability of fate. One of the central questions of the Agamemnon is whether the characters can truly be held responsible for their actions and choices. The Curse of Atreus makes the play’s cycle of violence seem inevitable. Likewise, Cassandra highlights in her prophecy that everything is preordained by fate. If the human characters are no more than victims of fate, then is the justice they suffer really just?

Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix by the Kodros Painter showing Ajax the Lesser raping Cassandra during the sack of Troy (ca. 440–430 BCE)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainJustice and fate also come to bear on the themes of religion and religious imagery, especially sacrificial imagery: Agamemnon’s death, for example, is characterized as a kind of perverted sacrifice. The role of the gods in enforcing justice and representing the inevitability of fate is also developed in the play.

Finally, the character of Clytemnestra inspires reflection on gender and politics. Routinely described as “man-like,” Clytemnestra brazenly flouts the (highly misogynistic) gender norms of her day, which subjugated women to men. Far from being dominated by Agamemnon (or even her lover Aegisthus), Clytemnestra exerts a formidable force in the play, speaking publicly before the male Chorus and taking decisive action against her husband. The play ends with Clytemnestra—a woman—in control of the government of Argos.

Reception

Aeschylus’ Agamemnon (along with the rest of the Oresteia) was well received in antiquity. Posthumous productions of the play began very early, likely around the 420s BCE. The Agamemnon and the Oresteia had a considerable impact on Sophocles and Euripides, both of whom adapted and reworked elements of Aeschylus’ plays in their own works, especially in their respective Electra plays. Later, in the Augustan period, the Roman Seneca composed an Agamemnon of his own, as well as a Thyestes—a gruesome, tragic adaptation of the tale of Atreus’ murder of Thyestes’ sons.

The Agamemnon was not widely read during the Middle Ages or Renaissance, but by the eighteenth century, the Oresteia trilogy had begun to circulate once again. Recreations and adaptations of the plays were especially popular in France; in 1797, for instance, Citizen Lemercier produced an Agamemnon in Paris, and in 1856 the novelist Alexandre Dumas translated the Oresteia into French. By the nineteenth century, Friederich Nietzsche and Richard Wagner had declared the Oresteia one of the most important achievements of the ancient Greeks.

There have also been more recent adaptations of the Agamemnon. Eugene O’Neill’s 1931 play cycle Mourning Becomes Electra, for example, retells the myth of the Oresteia in a Civil War setting. T. S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion, produced in 1939, is also loosely based on the Oresteia (though it was not particularly successful). Finally, Jean-Paul Sartre’s play Les Mouches (The Flies), published in 1942, transforms Agamemnon’s murder and Orestes’ revenge into a reflection on the ethical issues surrounding the Nazi occupation of France.

Today, the Agamemnon and the Oresteia remain among Aeschylus’ most widely-read and widely-admired works.

Translations

Translations of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon usually appear together with the other plays in the Oresteia trilogy (the Libation Bearers and the Eumenides). The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful English translations:

Smyth, Herbert W., trans. Aeschylus: Oresteia. Loeb Classical Library 146. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926: An old but reliable prose translation. It was replaced in the Loeb Classical Library by a new translation in 2008, but is still available online through the Perseus Project.

Lloyd-Jones, Hugh, trans. Oresteia. London: Duckworth, 1979: An accurate translation with helpful annotations, best suited for more advanced readers.

Harrison, Tony, trans. The Oresteia. London: Collings, 1981: A verse translation produced for performance.

Raphael, Frederic, and Kenneth McLeish, trans. The Serpent Son: Aeschylus’ Oresteia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981: A translation produced for a BBC performance of the trilogy.

Meineck, Peter, trans. Oresteia. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998: A translation produced for performance, with an introduction by Helene Foley.

Hughes, Ted, trans. The Oresteia. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999: A readable verse translation by a distinguished poet.

Collard, Christopher, trans. Oresteia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002: A clear translation with brief commentary.

Burian, Peter, and Alan Shapiro, trans. The Oresteia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003: Readable and accurate verse translation.

Sommerstein, Alan H., ed. and trans. Aeschylus: Oresteia. Loeb Classical Library 146. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008: An accurate prose translation; replaced Smyth’s 1926 translation in the Loeb Classical Library.

Lattimore, Richmond, trans. Aeschylus II: The Oresteia. 3rd ed. Edited by Mark Griffith and Glenn W. Most. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013: An accurate verse translation with a brief introduction and notes.

Hinds, Andy, and Martine Cuypers, trans. Aeschylus’ the Oresteia. London: Oberon Books, 2017: A verse translation produced for performance; contains minimal commentary.

Taplin, Oliver, trans. The Oresteia. London: W. W. Norton, 2018: An accurate and poetic translation with a helpful introduction.